The Little Fix

May 4th, 2011 // 2:45 pm @ Oliver DeMille

Sometimes small and simple things make all the difference. Malcolm Gladwell called this “the tipping point,” and an old proverb speaks of mere straws “breaking the camel’s back.” In my book FreedomShift I wrote about how three little things could—and should—change everything in America’s future.

Following is a little quote that holds the fix to America’s modern problems. This is a big statement. Many Americans feel that the United States is in decline, that we are facing serious problems and that Washington doesn’t seem capable of taking us in the right direction. People are worried and skeptical. Washington—whichever party is in power—makes promises and then fails to fulfill them.

What should America do? The answer is provided, at least the broad details, in the following quote. The famous Roman thinker Cicero is said to have given us this quote in 55 BC. However, it turns out that this quote was created in 1986 as a newspaper fabrication.[i] Still, the content of the quote carries a lot of truth:

“The budget should be balanced, the Treasury should be refilled, public debt should be reduced, the arrogance of officialdom should be tempered and controlled, and the assistance to foreign lands should be curtailed lest Rome become bankrupt.”

Consider each item:

- Balance the budget. There are various proposals to do this, nearly all of which require cutting entitlements and also foreign military expenditures. Many do not require raised tax rates. But most Americans would support moderate tax increases if Washington truly gets its outrageous spending habit under control. Paying more taxes in order to see our national debts paid off and our budgets balanced would be worth it—if, and only if, we first witness Washington really fix its spending problem.

- Refill the Treasury. This is seldom suggested in modern Washington. We have become so accustomed to debt, it seems, that the thought of maintaining a long-term surplus in Washington’s accounts is hardly ever mentioned.

- Reduce public debt. This is part of various proposals, and is a major goal of many American voters (including independents, who determine presidential elections).

- Temper and control the arrogance of officialdom. This is seldom discussed, but it is a significant reality in modern America. We have become a society easily swayed by celebrity, and this is bad for freedom.

- Curtail foreign aid. The official line is that the experts, those who “understand these things,” know why we must continue and even expand foreign aid, and that those who oppose this are uneducated and don’t understand the realities of the situation. The reality, however, is that the citizenry does understand that we can’t spend more than we have. Period. The experts would do well to figure this out.

The question boils down to this: Is the future of America a future of freedom or a future of big government? Our generation must choose.

The challenge so far is that the American voter wants less expensive government but also big-spending government programs. Specifically, we want government to stop spending for programs which benefit other people, but to keep spending for programs that benefit us directly.[ii] We want taxes left the same or decreased for us, but raised on others. We want small business to create more jobs, but we want small businesspeople to pay higher taxes (we don’t want to admit that by paying higher taxes they’ll naturally need to reduce the number of jobs they offer).

The modern American citizen wants the government programs “Rome” can offer, but we want someone else to pay for it. We elect leaders who promise smaller government, and then vote against them when they threaten a government program we enjoy.

Over time, however, we are realizing that we can’t have it both ways. We are coming to grips with the reality that to get our nation back on track we’ll need to allow real cuts that hurt. The future of America depends on how well we stick to our growing understanding that our government must live within its means.

[i] Discussed in Gary Shapiro, The Comeback: How Innovation Will Restore The American Dream.

[ii] See Meet the Press, April 24, 2011.

**********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Blog &Citizenship &Culture &Economics &Education &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History

Is America a Democracy, Republic, or Empire?

April 20th, 2011 // 7:09 am @ Oliver DeMille

Some in Washington are fond of saying that certain nations don’t know how to do democracy.

Anytime a nation breaks away from totalitarian or authoritarian controls, these “experts” point out that the people aren’t “prepared” for democracy.

But this is hardly the point.

A nation where the people aren’t prepared for democracy–but where a strong leader is prepared for tyranny–is still better off as a democracy.

A nation where the people aren’t prepared for democracy but where an elite class is prepared for aristocracy is still better off as a democracy.

A nation where the people aren’t prepared for democracy but where a socialist or fundamentalist religious bureaucracy is prepared to rule is still better off as a democracy.

Whatever the people’s inadequacies, they will do better than the other, class-dominant forms of government.

Winston Churchill was right:

“Democracy is the worst form of government–except for all those others that have been tried.”

False Democracy

When I say “democracy,” I am of course not referring to a pure democracy where the masses make every decision; this has always turned to mob rule through history.

Of Artistotle’s various types and styles of democracy, this was the worst. The American founders considered this one of the least effective of free forms of government.

Nor do I mean a “socialist democracy” as proposed by Karl Marx, where the people elect leaders who then exert power over the finances and personal lives of all citizens.

Whether this type of government is called democracy (e.g. Social Democrats in many former Eastern European nations) in the Marxian sense or a republic (e.g. The People’s Republic of China, The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics–USSR, etc.), it amounts to the same oligarchic model of authoritarian rule.

Marx used the concept of democracy–he called it “the battle for democracy”–to argue for the working classes to rise up against the middle and upper classes and take back their power.

Ironically, he believed the masses incapable of such leadership, and felt that a small group of elites, the “vanguard”, would have to do the work of the masses for them.

This argument assumes an oligarchic view of the world, and the result of attempted Marxism has nearly always been dictatorial or oligarchic authoritarianism.

In this attitude Marx follows his mentor Hegel, who discounted any belief in the power or wisdom of the people as wild imaginings (see Mortimer Adler’s discussion on “Monarchy” in the Syntopicon).

The American founders disagreed entirely with this view.

A Democratic Republic

The type of democracy we need more of in the world is constitutional representative democracy, with:

A written constitution that separates the legislative, executive and judicial powers. Limits all with checks and balances, and leaves most of the governing power in the hands of the people and local and regional, rather than national, government institutions.

In such a government, the people have the power to elect their own representatives who participate at all levels. Then the people closely oversee the acts of government.

One other power of the people in a constitutional representative democratic republic is to either ratify or reject the original constitution.

Only the support of the people allows any constitution to be adopted (or amended) by a democratic society.

The American framers adopted Locke’s view that the legislative power was closest to the people and should have the sole power over the nation’s finances.

Thus in the U.S. Constitution, direct representatives of the people oversaw the money and had to answer directly to the people every two years.

Two Meanings of “Democracy”

There are two ways of understanding the term democracy. One is as a governmental form–which is how this article has used the word so far. The other is as a societal format.

There are four major types of societies:

- A chaotic society with no rules, laws or government

- A monarchical society where one man or woman has full power over all people and aspects of the society

- An aristocratic society where a few people–an upper class–control the whole nation

- A democratic society where the final say over the biggest issues in the nation comes from the regular people

As a societal form, democracy is by far the best system.Montesquieu, who was the source most quoted at the American Constitutional Convention, said:

“[Democracy exists] when the body of the people is possessed of the supreme power.”

In a good constitutional democracy, the constitution limits the majority from impinging upon the inalienable rights of a minority–or of anyone at all.

Indeed, if a monarchical or aristocratic society better protects the rights of the people than a democratic nation, it may well be a more just and free society.

History has shown, however, that over time the people are more likely to protect their rights than any royal family or elite class.

When the many are asked to analyze and ratify a good constitution, and then to protect the rights of all, it turns out they nearly always protect freedom and just society better than the one or the few.

It is very important to clarify the difference between these two types of democracy–governmental and societal.

For example, many of the historic Greek “democracies” were governmental democracies only. They called themselves democracies because the citizens had the final say on the governmental structure and elections–but only the upper class could be citizens.

Thus these nations were actually societal aristocracies, despite being political democracies.

Plato called the societal form of democracy the best system and the governmental format of democracy the worst.

Clearly, knowing the difference is vital.

Aristotle felt that there are actually six major types of societal forms.

A king who obeys the laws leads a monarchical society, while a king who thinks he is above the law rules a tyrannical society.

Likewise, government by the few can either have different laws for the elite class or the same laws for all people, making oligarchy or aristocracy.

In a society where the people are in charge, they can either rule by majority power (he called this democracy) or by wise laws, protected inalienable rights and widespread freedom (he called this “mixed” or, as it is often translated, “constitutional” society).

Like Plato, Aristotle considered the governmental form of democracy bad, but better than oligarchy or tyranny; and he believed the societal form of democracy (where the people as a mass generally rule the society) to be good.

Democracy or Republic?

The authors of The Federalist Papers tried to avoid this confusion about the different meanings of “democracy” simply by shortening the idea of a limited, constitutional, representative democracy to the term “republic.”

A breakdown of these pieces is enlightening:

- Limited (unalienable rights for all are protected)

- Constitutional (ratified by the people; the three major powers separated, checked and balanced)

- Representative (the people elect their leaders, using different constituencies to elect different leaders for different governmental entities–like the Senate and the House)

- Democracy (the people have the final say through elections and through the power to amend the constitution)

The framers required all state governments to be this type of republic, and additionally, for the national government to be federal (made up of sovereign states with their own power, delegating only a few specific powers to the national government).

When we read the writings of most of the American founders, it is helpful to keep this definition of “republic” in mind.

When they use the terms “republic” or “a republic” they usually mean a limited, constitutional, representative democracy like that of all the states.

When they say “the republic” they usually refer to the national-level government, which they established as a limited, constitutional, federal, representative democracy.

At times they shorten this to “federal democratic republic” or simply democratic republic.

Alexander Hamilton and James Wilson frequently used the term “representative democracy,” but most of the other founders preferred the word “republic.”

A Global Problem

In today’s world the term “republic” has almost as many meanings as “democracy.”

The term “democracy” sometimes has the societal connotation of the people overseeing the ratification of their constitution. It nearly always carries the societal democracy idea that the regular people matter, and the governmental democracy meaning that the regular people get to elect their leaders.

The good news is that freedom is spreading. Authoritarianism, by whatever name, depends on top-down control of information, and in the age of the Internet this is disappearing everywhere.

More nations will be seeking freedom, and dictators, totalitarians and authoritarians everywhere are ruling on borrowed time.

People want freedom, and they want democracy–the societal type, where the people matter. All of this is positive and, frankly, wonderful.

The problem is that as more nations seek freedom, they are tending to equate democracy with either the European or Asian versions (parliamentary democracy or an aristocracy of wealth).

The European parliamentary democracies are certainly an improvement over the authoritarian states many nations are seeking to put behind them, but they are inferior to the American model.

The same is true of the Asian aristocratic democracies.

Specifically, the parliamentary model of democracy gives far too much power to the legislative branch of government, with few separations, checks or balances.

The result is that there are hardly any limits to the powers of such governments. They simply do whatever the parliament wants, making it an Aristotelian oligarchy.

The people get to vote for their government officials, but the government can do whatever it chooses–and it is run by an upper class.

This is democratic government, but aristocratic society. The regular people in such a society become increasingly dependent on government and widespread prosperity and freedom decrease over time.

The Asian model is even worse. The governmental forms of democracy are in place, but in practice the very wealthy choose who wins elections, what policies the legislature adopts, and how the executive implements government programs.

The basic problem is that while the world equates freedom with democracy, it also equates democracy with only one piece of historical democracy–popular elections.

Nations that adopt the European model of parliamentary democracy or the Asian system of aristocratic democracy do not become societal democracies at all–but simply democratic aristocracies.

Democracy is spreading–if by democracy we mean popular elections; but aristocracy is winning the day.

Freedom–a truly widespread freedom where the regular people in a society have great opportunity and prosperity is common–remains rare around the world.

The Unpopular American Model

The obvious solution is to adopt the American model of democracy, as defined by leading minds in the American founding: limited, constitutional, representative, federal, and democratic in the societal sense where the regular people really do run the nation.

Unfortunately, this model is currently discredited in global circles and among the world’s regular people for at least three reasons:

1. The American elite is pursuing other models.

The left-leaning elite (openly and vocally) idealize the European system, while the American elite on the right prefers the Asian structure of leadership by wealth and corporate status.

If most of the intelligentsia in the United States aren’t seeking to bolster the American constitutional model, nor the elite U.S. schools that attract foreign students on the leadership track, it is no surprise that freedom-seekers in other nations aren’t encouraged in this direction.

2. The American bureaucracy around the world isn’t promoting societal democracy but rather simple political democracy–popular elections have become the entire de facto meaning of the term “democracy” in most official usage.

With nobody pushing for limited, constitutional, federal, representative democratic republics, we get what we promote: democratic elections in fundamentally class-oriented structures dominated by elite upper classes.

3. The American people aren’t all that actively involved as democratic leaders.

When the U.S. Constitution was written, nearly every citizen in America was part of a Town Council, with a voice and a vote in local government. With much pain and sacrifice America evolved to a system where every adult can be such a citizen, regardless of class status, religious views, gender, race or disability.

Every adult now has the opportunity to have a real say in governance. Unfortunately, we have over time dispensed with the Town Councils of all Adults and turned to a representative model even at the most local community and neighborhood level.

As Americans have ceased to participate each week in council and decision-making with all adults, we have lost some of the training and passion for democratic involvement and become more reliant on experts, the press and political parties.

Voting has become the one great action of our democratic involvement, a significant decrease in responsibility since early America.

We still take part in juries–but now even that power has been significantly reduced–especially since 1896.

In recent times popular issues like environmentalism and the tea parties have brought a marked increase of active participation by regular citizens in the national dialogue.

Barack Obama’s populist appeal brought a lot of youth into the discussion. The Internet and social media have also given more power to the voice of the masses.

When the people do more than just vote, when they are involved in the on-going dialogue on major issues and policy proposals, the society is more democratic–in the American founding model–and the outlook for freedom and prosperity brightens.

The Role of the People

Human nature being what it is, no people of any nation may be truly prepared for democracy.

But–human nature being what it is–they are more prepared to protect themselves from losses of freedom and opportunity than any other group.

Anti-democratic forces have usually argued that we need the best leaders in society, and that experts, elites and those with “breeding,” experience and means are most suited to be the best leaders.

But free democratic societies (especially those with the benefits of limited, constitutional, representative, and locally participative systems) have proven that the right leaders are better than the best leaders.

We don’t need leaders (as citizens or elected officials) who seem the most charismatically appealing nearly so much as we need those who will effectively stand for the right things.

And no group is more likely to elect such leaders than the regular people.

It is the role of the people, in any society that wants to be or remain free and prosperous, to be the overseers of their government.

If they fail in this duty, for whatever reason, freedom and widespread prosperity will decrease. If the people don’t protect their freedoms and opportunities, despite what Marx thought, nobody will.

No vanguard, party or group of elites or experts will do as much for the people as they can do for themselves. History is clear on this reality.

We can trust the people, in America and in any other nation, to promote widespread freedom and prosperity better than anyone else.

Two Challenges

With that said, we face at least two major problems that threaten the strength of our democratic republic right now in the United States.

First, only a nation of citizen-readers can maintain real freedom. We must deeply understand details like these:

- The two meanings of democracy

- The realities and nuances of ideas such as: limited, constitutional, federal, representative, locally participative, etc.

- The differences between the typical European, Asian, early American and other models competing for support in the world

- …And so on

In short, we must study the great classics and histories to be the kind of citizen-leaders we should be.

The people are better than any other group to lead us, as discussed above, but as a people we can know more, understand more, and become better leaders.

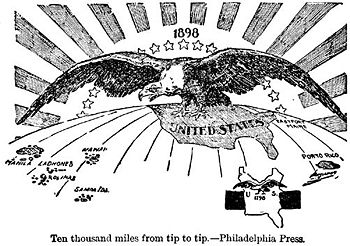

As George Friedman has argued, we now control a world empire larger than any in history, whether we want to or not.

Yet a spirit of democratic opportunity, entrepreneurial freedom, inclusive love of liberty, freedom from oppressive class systems, and promotion of widespread prosperity is diametrically opposed to the arrogant, selfish, self-elevating, superiority-complex of imperialism.

This very dichotomy has brought down some of the greatest free nations of history.

On some occasions this challenge turned the home nation into an empire, thus killing the free democratic republic (e.g. Rome).

Other nations lost their power in the world because the regular people of the nation did not reconcile their democratic beliefs with the cruelty of imperial dominance and force (e.g. Athens, ancient Israel).

At times the colonies of an empire used the powerful democratic ideals of the great power against them and broke away.

At times the citizens of the great power refused to support the government in quelling rebellions with which they basically agreed (e.g. Great Britain and its relations with America, India, and many other former colonies).

Many of the great freedom thinkers of history have argued against empire and for the type of democratic republic the American framers established–see for example Herodotus, Thucydides, Aristotle, the Bible, Plutarch, Tacitus, Augustine, Montaigne, Locke, Montesquieu, Gibbon, Jefferson, The Declaration of Independence, and Madison, among others.

The Federalist mentions empire or imperialism 53 times, and not one of the references is positive.

In contrast, the main purpose of the Federalist Papers was to make a case for a federal, democratic republic.

Those who believe in American exceptionalism (that the United States is an exception to many of the class-oriented patterns in the history of nations) now face their greatest challenge.

Will America peacefully and effectively pull back from imperialism and leave dozens of nations successfully (or haltingly) running themselves without U.S. power?

Will it set its best and brightest to figuring out how this can be done? Or to increasing the power of empire?

Empire and Freedom

Some argue that the United States cannot divest itself of empire without leaving the world in chaos.

This is precisely the argument nearly all upper classes, and slave owners, make to justify their unprincipled dominance over others.

The argument on its face is disrespectful to the people of the world.

Of course few people are truly prepared to run a democracy–leadership at all levels is challenging and at the national level it is downright overwhelming.

But, again–the people are more suited to oversee than any other group.

And without the freedom to fail, as Adam Smith put it, they never have the dynamic that impels great leaders to forge ahead against impossible odds. They will never fly unless the safety net is gone.

The people can survive and sometimes even flourish without elite rule, and the world can survive and flourish without American empire.

A wise transition is, of course, the sensible approach, but the arrogance of thinking that without our empire the world will collapse is downright selfish–unless one values stability above freedom.

How can we, whose freedom was purchased at the price of the lives, fortunes and sacred honor of our forebears, and defended by the blood of soldiers and patriots in the generations that followed, argue that the sacrifices and struggles that people around the world in our day might endure to achieve their own freedom and self- determination constitute too great a cost?

The shift will certainly bring major difficulties and problems, but freedom and self-government are worth it.

The struggles of a free people trying to establish effective institutions through trial, error, mistakes and problems are better than forced stability from Rome, Madrid, Beijing, or even London or Washington.

America can set the example, support the process, and help in significant ways–if we’ll simply get our own house in order.

Our military strength will not disappear if we remain involved in the world without imperial attitudes or behaviors. We can actively participate in world affairs without adopting either extreme of isolationism or imperialism.

Surely, if the world is as dependent on the U.S. as the imperial-minded claim, we should use our influence to pass on a legacy of ordered constitutional freedom and learning self-government over time rather than arrogant, elitist bureaucratic management backed by military might from afar.

If Washington becomes the imperial realm to the world, it will undoubtedly be the same to the American people. Freedom abroad and at home may literally be at stake.

The future will be significantly impacted by the answers to these two questions:

Will the American people resurrect a society of citizen readers actively involved in daily governance?

Will we choose our democratic values or our imperialistic attitudes as our primary guide for the 21st Century?

Who are we, really?

Today we are part democracy, part republic, and part empire.

Can we find a way to mesh all three, even though the first two are fundamentally opposed to the third?

Will the dawn of the 22nd Century witness an America free, prosperous, strong and open, or some other alternative?

If the United States chooses empire, can it possibly retain the best things about itself?

Without the Manifest Destiny proposed by the Founders, what alternate destiny awaits?

Above all, will the regular citizens–in American and elsewhere–be up to such leadership?

No elites will save us. It is up to the people.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Constitution &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History &Leadership &Liberty &Politics &Postmodernism &Statesmanship

What type of government does America have today?

March 26th, 2011 // 10:17 am @ Oliver DeMille

“It’s a Republic; if you can keep it…”

Property Rights

- Free democracies protect the property of all.

- Socialist nations protect the property of none.

- Monarchies consider all property the estate of the king.

- Aristocracies have one set of property and investment laws for the very rich and a different one for the rest.*

Taxation

- Free democracies assess tax money fairly from all the people to cover vital, limited government roles.

- Socialist societies take money from the rich and redistribute it to the poor.

- Dictatorial monarchies take money from everyone and give it to the dictator.

- Aristocracies take money from the middle and lower classes and give it to rich bankers, owners of big companies (“too big to fail”), and other powerful and wealthy special interests in bailouts and government contracts.*

Information

- In free democracies it is legal for the people to withhold information from the government (e.g. U.S. Fifth Amendment, right to remain silent, etc.) but illegal for the government to withhold information from or lie to the people.

- In socialist societies, dictatorial monarchies, and aristocracies, it is legal for the government and government agents to lie to the people but illegal for the people to lie to the same government agents.*

Success

- In free democracies, the measure of success and the popular goal of the people is to be good and positively contribute to society.

- In socialist societies, the measure of success and the popular goal of the people is to become government officials and receive the perks of office.

- In dictatorial monarchies, the measure of success and the popular goal of the people is to please the monarch.

- In aristocratic societies, the measure of success and the popular goal of the people is to obtain wealth and/or celebrity.*

Right to Bear Arms

- In free democracies all the people hold the right to bear arms.

- In socialist nations and monarchies, only government officials are allowed to have weapons.

- In aristocratic societies only the wealthy and government officials are allowed to have many kinds of weapons.*

Immigration

- Free democracies open their borders to all, especially immigrants in great need.

- Socialist and dictatorial monarchies build fences to keep people in.

- Aristocracies build fences to keep people out, especially immigrants in great need.*

*The current United States

Please share this with everyone you think should read it using the links below.

*****************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Constitution &Culture &Economics &Foreign Affairs &Government &History &Liberty

Ten Important Trends

March 16th, 2011 // 10:42 am @ Oliver DeMille

The obvious big trend right now is that oil prices threaten to reverse economic recovery across the globe.[i] The recent problems with nuclear power in Japan only promise to exacerbate the oil crisis. And the concern about a second mortgage bubble lingers.[ii] Food and other retail prices are increasing at alarming levels while unemployment rates remain high. In addition, some trends and current affairs promise to significantly influence the years ahead despite receiving little coverage in the nightly news. Here are ten such trends that every American should know about:

- “In the wake of the financial crisis, the United States is no longer the leader of the global economy, and no other nation has the political and economic leverage to replace it.”[iii] Increased international conflicts are ahead.

- The new e-media is revolutionizing communication and fueling actual revolutions from the Middle East to North Korea.[iv]

- The new media is also differentiated by both political views and class divisions,[v] meaning that people of different views hardly ever listen to each other. This is creating more divisiveness in society.

- In response to the rise of the Tea Parties, some top leaders of American foreign policy feel that Washington must find ways to promote a “liberal and cosmopolitan world order” and simultaneously “find some way to satisfy their angry domestic constituencies…”[vi] The disconnect between the American citizenry and elites continues to increase. So does the wage disparity between American elites and everyone else.[vii]

- The evidence suggests that “teams, not individuals, are the leading force behind entrepreneurial startups.”[viii] This has been a topic of debate for some time, and a new book (The Invention of Enterprise by Landes, Mokyr and Baumol[ix]) outlines the history of entrepreneurship from ancient to modern times.

- As Leah Farrall put it, “Al Qaeda is stronger today than when it carried out the 9/11 attacks. Accounts that contend that it is on the decline treat the central al Qaeda organization separately from its subsidiaries and overlooks its success in expanding its power and influence through them.”[x]

- One trend is outlined clearly by a new book title: Alone Together: Why We Expect More From Technology and Less From Each Other.[xi]

- In contrast to popular wisdom, democracy and modernization are significantly increasing the influence of religion in many developing regions around the world.[xii]

- More people are using Facebook to connect more with their children—in one survey this included 64% of those surveyed.[xiii]

- While governments—at national, provincial/state and local levels—are increasingly strapped for cash and struggling to balance budgets and service looming debts, many multinational corporations “sit on enormous stockpiles of cash…”[xiv] This reality is giving strength to the argument in some circles that the future of governance should be put in the hands of corporations rather than outdated dependence on inefficient government.[xv]

[i] “The 2011 oil shock,” The Economist, March 5th, 2011.

[ii] Consider the ideas in “Bricks and slaughter,” The Economist, March 5th, 2011.

[iii] Ian Bremmer and Nouriel Roubini, “A G-Zero World,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2011.

[iv] See James Fallows, “Learning to Love the New Media” and Robert S. Boynton, “North Korea’s Digital Underground,” The Atlantic, April 201.

[v] Op. cit., Fallows.

[vi] See Walter Russell Mead, “The Tea Party and American Foreign Policy,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2011.

[vii] See “Gaponomics,” The Economist, March 12th, 2011.

[viii] See Martin Ruef, The Entrepreneurial Group, 2011, Kauffman.

[ix] 2011, Kauffman.

[x] Leah Farrall, “How al Qaeda Works,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2011.

[xi] By Sherry Turkle, 2011, Basic Books.

[xii] See book reviews, Foreign Affairs, March/April 2011.

[xiii] Redbook, April 2011.

[xiv] See op. cit., Bremmer and Roubini.

[xv] See the following: Shell Scenarios; “Tata sauce,” The Economist, March 5th, 2011; Adam Segal, Advantage: How American Innovation Can Overcome the Asian Challenge, 2011, Council on Foreign Relations; and “Home truths,” The Economist, March 5th, 2011.

Category : Blog &Current Events &Economics &Entrepreneurship &Family &Foreign Affairs &Government &Independents &Information Age &Politics &Science

Egypt, Freedom, & the Cycles of History

February 14th, 2011 // 12:31 pm @ Oliver DeMille

*Note: If you like this article, you’ll love Oliver’s latest book, FreedomShift: 3 Choices to Reclaim America’s Destiny.

I look at the young protesters who gathered in downtown Amman today, and the thousands who gathered in Egypt and Tunis, and my heart aches for them. So much human potential, but they have no idea how far behind they are—or maybe they do and that’s why they’re revolting.

“Egypt’s government has wasted the last 30 years—i.e., their whole lives—plying them with the soft bigotry of low expectations: ‘Be patient. Egypt moves at its own pace, like the Nile.’ Well, great. Singapore also moves at its own pace, like the Internet.” —Thomas L. Freidman

A World of Demonstrations

In the fall of 2010 I listened to a famous French author speaking as a guest on a television talk show. He expressed concern with the Tea Party in the United States and wondered how democracy could survive “such a thing.”

A few weeks later his own nation was shut down by rioting protestors—middle class managers and professionals burning cars in the streets and throwing homemade pop bottle firebombs.

I wondered if he had revised his worries about what he called Tea Party “extremism.” In the U.S. the peaceful demonstrations were much more civil and positive (and, as it turns out, effective) than their French counterparts.

In the last year we’ve witnessed demonstrations, protests, and even a few violent riots across the globe—from Greece to Ireland, Paris to Washington, Iran to Cairo, and beyond. It is interesting to see how the left and right in the U.S. have responded.

The left welcomed demonstrations against governments that were run by the privileged class in Iran, Greece, Ireland, Egypt, China and even France. Instead of feeling threatened by such uprisings, they tended to see them as the noble voice of humanity yearning for freedom from oppression.

In contrast, they saw marches and demonstrations from the American right as somehow dangerous to democracy. In such a view, protests are owned by the left and those on the right aren’t allowed to use such techniques—they are supposed to better behaved.

In contrast, the right tended to view recent right-leaning town meetings and D.C. demonstrations in the United States as progressive, while viewing the French, Irish, Greek and Middle East protests with critical eyes.

The old meaning of “conservative” was to simply want things to stay the same, and in world affairs many American conservatives seem to prove this definition.

An uprising in Iran or Egypt, as much as one might identify with the people’s desire for freedom, feels threatening and disturbing to many on the right.

The Cycles

The demonstrations and the diverse ways of viewing them is a natural result of a major shift we are experiencing in the world. Strauss and Howe called it “The Fourth Turning,” a great cyclical shift from an age of long-term peace and prosperity to a time of challenge and on-going crises.

We have experienced many such shifts in history (e.g. the American revolutionary era, the Civil War period, the era of Great Depression and World War II), but that doesn’t soften the blow of experiencing it firsthand in our generation.

Following the cycles of history, we have lived through the great catalyst (9/11) which brought on the new era of challenge, just like earlier generations faced their catalytic events (e.g. the Boston Tea Party, the election of Abraham Lincoln, or the Stock Market crash of 1929).

We are now living in a period of high stress and high conflict, just as our forefathers did in the tense periods of the 1770s, 1850s and 1930s. If the cycles hold true in our time, we can next expect some truly major crisis—the last three being the attack on Pearl Harbor, the first shots of the Civil War, and the fighting at Lexington and Concord.

These realities are part of our genetic and psychic history, even if we haven’t personally researched the trends and history books. We seem to “know” that challenges are ahead, and so we worry about the latest world and national news event.

“Will this ignite the fire?” “Will this change everything?” “Is this it—the start of major crisis?” Conservatives, liberals, independents—we nearly all ask these questions, if only subconsciously.

Conservatives tend to believe that major crisis will come from the “mismanagement of the left,” while liberals are inclined to think the problems will be caused by the extremism of the right.

Independents have a tendency to feel that our challenges will come from both Republicans and Democrats—either working together in the wrong ways or getting distracted from critical issues while fighting each other at precisely the wrong time.

Add to this strain the fact that we are simultaneously shifting from the industrial to the information age, and it becomes understandable that the pressure is building in many places in today’s world.

The shift from the agricultural age to the industrial age brought the Civil War, Bismarck’s Wars (known to many in Europe as the first great war—a generation before World War I), and the Asian upheaval as it shifted from the age of warlords to modern empires.

Today we have mostly forgotten how drastic such a change was, and how traumatically it impacted the world.

The Egypt Crisis

The bad news is: if the cycles and trends of history hold, we will likely relive such world-changing events in the decades ahead. As for Egypt, our reactions are telling us more about ourselves than about the Arab world.

Knee-jerk liberalism thrills at another people rising up against authoritarianism but worries that the extreme religious nature of some of the militants will bring the wrong outcomes.

Knee-jerk conservatism reinforces its view that the middle east is the world’s problem area, that we should just get out of that region (or get a lot more involved), and that stability is more important than things like freedom and opportunity for the Egyptian people.

Deep thinkers from all political views see that we now live in the age of demonstrations. The worldwide shift from decades of relative peace and prosperity to a time of recurring crises is putting pressure on people everywhere.

Some protest the reduction of government pensions and programs as nations try to figure out how to get their financial houses in order. Others demonstrate against governments that respond to major economic crises with increased spending, stimulus and government programs.

Still others riot against authoritarian governments that haven’t allowed the people a true democratic voice in the direction of their nation or society.

When we shift from an industrial era of peace and prosperity to an information-age epoch of crisis and challenge, people in all walks of life feel the pressure and anxiety of change. This manifests itself in relationship, organizational, financial and family stress, as well as cultural, class, religious, political and societal tensions. We are witnessing all of these in this generation.

Egypt may spark a major world crisis, and indeed many feel that the Egyptian challenge is the biggest foreign policy crisis of Obama’s presidency. As Thomas L. Friedman put it, on a more global scale:

“There is a huge storm coming, Israel. Get out of the way.”

President Bush’s supporters are using Egypt to bolster the view that Bush’s attempts to establish democracy in the Arab world was wise foresight, and Obama supporters hope that a re-democratized Egypt can stand as “beacon to the region.”

If the Egyptian uprising becomes the start of pan-Arabism led by the Muslim Brotherhood (or something like it), this will certainly bring significant changes to the Middle East and to international relations across the board.

On the other hand, a similar outcome could result from a totalitarian crackdown that extinguishes the will of the Egyptian people to fight for legitimate reform. The most likely result may be what has happened more often recently: the replacement of authoritarian government with a powerful oligarchy ruling the nation.

The American Crisis

How the United States responds to any of these scenarios, or whatever else may happen, will have a significant impact on world policy.

Add to this at least two concerns: Serious inflation is already a growing reality and increasing danger, and many are watching to see the impact on the price of oil on our economy.

If the cost of gasoline goes above $5 or $6 or, say, $9 per gallon in the U.S., what will happen to 9.6% unemployment, state and local governments that are already close to bankruptcy, and a reeling economy just barely emerging from the Great Recession?

If the Egypt Crisis doesn’t ignite a major world or American crisis, something else will. That’s the reality of our place in the cycles of history. Challenges are ahead for our nation.

This is true in any generation, but it is even more pronounced in the generations where we shift from an era of peace and prosperity to an epoch of crisis and challenge. As we also move into the information age, we have our work cut out for us.

Futurist Alvin Toffler wrote:

“A new civilization is emerging in our lives. This new civilization brings with it new family styles; changed ways of working, loving and living; a new economy; new political conflicts. Millions are already attuning their lives to the rhythms of tomorrow. Others, terrified of the future, are engaged in a desperate, futile flight into the past and are trying to restore the dying world that gave them birth. The dawn of this new civilization is the single most explosive fact of our lifetimes. It is the central event—the key to understanding the years immediately ahead.”

The good news is that in such times of challenge we have the opportunity to significantly improve the world in important ways.

The Revolutionary era brought us the Constitution and the implementation of free enterprise and a classless society, the Civil War ended slavery, and the World War II era brought us into the industrial age with increasing opportunity for social equity and individual prosperity.

Freedom, free enterprise, increased caring and more widespread economic opportunities are likely ahead if we as a society refocus on the principles that work. Liberals, conservatives and independents have a lot to teach each other in this process, and we all have a lot to learn.

The biggest danger is that the age of demonstrations will lead to an age of dominance by elites—in Egypt, in Europe, in Asia, and in North America. Unfortunately, popular demonstrations are most often followed by the increased power of one elite group or another.

Though this is the worst-case scenario, it is also a leading trend in our times. In contrast, only a society led by the people can truly be free, and only such a future can turn our challenging era into a truly better world.

Each of us must take responsibility for the future, rather than leaving the details to experts. Many citizens in Egypt are trying to do this—for good or ill.

In America, we need more regular citizens to be leaders so we can meet this generational challenge as our forefathers did theirs—leaving posterity with greater freedom and opportunity.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Current Events &Featured &Foreign Affairs &Government &History &Liberty &Politics