The Social Animal

April 20th, 2011 // 7:31 am @ Oliver DeMille

A review of the book The Social Animal: A Story of Love, Character and Achievement by David Brooks

There are at least three major types of writing. The first might be called Shakespeare’s method, which includes the telling of stories with deep symbolic and archetypal lessons. Many of the great world religious texts used this approach. The Greeks referred to this as poetry, though the meaning of “poetry” is much more limited in modern usage. In the contemporary world we often call this type of writing fiction, though this is a misnomer since the stories used are not actually untrue—they are, many of them, literally true, and nearly all of them are symbolically true. This could also be called the Inspirational style of writing.

There are at least three major types of writing. The first might be called Shakespeare’s method, which includes the telling of stories with deep symbolic and archetypal lessons. Many of the great world religious texts used this approach. The Greeks referred to this as poetry, though the meaning of “poetry” is much more limited in modern usage. In the contemporary world we often call this type of writing fiction, though this is a misnomer since the stories used are not actually untrue—they are, many of them, literally true, and nearly all of them are symbolically true. This could also be called the Inspirational style of writing.

A second kind of writing can be summarized as Tocqueville’s method, or the philosopher’s style. Called prose, non-fiction, or editorializing, this type of literature consists of the author sharing her views, thoughts, questions, analyses and conclusions. Writers in this style see no need to document or prove their points, but they do make a case for their ideas. This way of writing gave the world many of the great classics of human history—in many fields of thought spanning the arts, sciences, humanities and practical domains. This writing is Authoritative in style, meaning that the author is interested mostly in ideas (rather than proof or credibility) and writes as her own authority on what she is thinking.

The third sort of writing, what I’ll call Einstein’s method, attempts to prove its conclusions using professional language and appealing to reason, experts or other authority. Most scientific works, textbooks, and research-based books on a host of topics apply this method. The basis of such writing is to clearly show the reader the sources of assumptions, the progress of the author’s thinking, and the basis behind each conclusion. Following the scientific method, this modern “Objective” style of writing emphasizes the credibility of the conclusions—based on the duplicable nature of the research and the rigorous analysis and deduction. There are few leaps of logic in this kind of prose.

Each type of writing has its masters, and all offer valuable contributions to the great works of human literature. This is so obvious that it hardly needs to be said, but we live in a world where the third, Objective, style of writing is the norm and anything else is often considered inferior. Such a conclusion, ironically, is not a scientifically proven fact. Indeed, how can science prove that anything open to individual preference and taste is truly “best?” For example, such greats as Churchill, Solzhenitsyn and Allan Bloom (author of The Closing of the American Mind) have shown that “Tocqueville’s” style is still of great value in modern times—as do daily op eds in our leading newspapers and blogs. Likewise, our greatest plays, movies and television programs demonstrate that the Shakespearean method still has great power in our world.

That said, David Brooks’ new book The Social Animal: A Story of Love, Character and Achievement manages to combine all three styles in one truly moving work. I have long considered Brooks one of my favorite authors. I assigned his book Bobos in Paradaise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There as an undergraduate and graduate college text for several years, and I have recommended his book On Paradise Drive to many students and executives who wanted to understand American and modern culture. In one of the best descriptions of our society ever written, he outlined the new realities experienced by the “average” American citizen, who he called “Patio Man.” I have also enjoyed many of his editorials in The New York Times—and the ongoing, albeit unofficial and indirect, “debate” between his columns and those of Thomas L. Friedman, Paul Krugman, George Will and, occasionally, Peggy Noonan.

The Social Animal is, in my opinion, his best work to date. In fact, it is downright brilliant. I am not suggesting that it approaches Shakespeare, of course. But who does? Still, the stories in The Social Animal flow like Isaac Asimov meets Ayn Rand. It doesn’t boast deep scientific technical writing, as Brooks himself notes. Indeed, Brooks doesn’t even attempt to produce a great Shakespearean or scientific classic. But he does effectively weave the three great styles of writing together, and in the realm of philosophical writing this book is similar to Tocqueville’s Democracy in America. The content of the book, in fact, is as close as we may ever see to a 21st century update to Tocqeville (1830s) and Bryce (1910s).

I know this is high praise, and in our modern era with its love of objective analysis, such strong language is suspect in “educated” circles. But my words are not hyperbole. This is an important book. It is one of the most important books we’ve seen in years—probably since Fareed Zakaria’s The Post-American World or Daniel Pink’s A Whole New Mind. This book is in the same class as Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind, Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations, Strauss and Howe’s The Fourth Turning, or Philip Bobbitt’s The Shield of Achilles. It is as significant as any article in Foreign Affairs since Richard Gardner’s writings. It reads like Steven Pinker channelling Alexis de Tocqueville. The language is, well, beautiful, but beautiful in the modern sense, like the writings of Laura Munson or Sandra Tsing Loh.

The book also manages to bridge political views—I think liberals will find it moving and conservatives will find it convincing. It is not exactly Centrist, but neither is it patently Right nor Left. It will appeal to independents and people from all political perspectives. If it has a political leaning, it is the party of Common Sense—backed by meticulous research.

Moreover, The Social Animal clouds typical publishing stereotypes. I’m not sure where big bookstores will shelve it. It is a book on culture, politics, education, and career. It is a book about entertainment, marriage and language. It is about the upper, middle and lower classes in modern American society, how they interrelate and what challenges are ahead as they clash. It is about current events and future challenges. It is, above all, a book about success. It goes well beyond books on Habits or The Secret or even “Acres of Diamonds.”

As Brooks himself put it:

“Over the centuries, zillions of books have been written about how to succeed. But these tales are usually told on the surface level of life. They describe the colleges people get into, the professional skills they acquire, the conscious decisions they make, and the tips and techniques they adopt to build connections and get ahead. These books often focus on an outer definition of success, having to do with IQ, wealth, prestige, and worldly accomplishments.

“This story [The Social Animal] is told one level down. This success story emphasizes the role of the inner mind—the unconscious realm of emotions, intuitions, biases, longings….

“…we are not primarily the products of our conscious thinking. We are primarily the products of thinking that happens below the level of awareness.”

Brooks argues:

“The research being done today reminds us of the relative importance of emotion over pure reason, social connections over individual choice, character over IQ, emergent, organic systems over linear, mechanistic ones, and the idea that we have multiple selves over the idea that we have a single self.”

The book deals with such intriguing topics as:

- Modern dating and courtship

- Today’s marriages and what makes them succeed—or not

- The scientific versus popular views of child development

- Cultural trends such as global-warming awareness assemblies in high schools

- The scientific foundations of violence

- The kind of decision-making that leads to success versus mediocrity and failure

- A veritable manual for success in college

- The powerful leadership techniques of priming, anchoring, framing, limerance, fractals, metis and multiparadigm teams, among others (it is worth reading the book just for this)

- How to “ace” job interviews

- The new phases of life progression

- Effectively starting a new business—the steps, techniques, values and needed character traits

- Leadership in the modern corporation

- How to win a revolution by only making a call for small reforms

- The effectiveness of a talent for oversimplification

- The supreme power of a life’s viewpoint

The Social Animal struck a personal note with me because it brilliantly describes the true process of great mentoring that more of our teachers need to adopt and that I wrote about with Tiffany Earl in our book The Student Whisperer. I have seldom seen truly great teaching described better.

This book is primarily about success—specifically success in our complex modern world—but at a deeper level it is about happiness. Brooks writes:

We still have admissions committees that judge people by IQ measures and not by practical literacy. We still have academic fields that often treat human beings as rational utility-maximizing individuals. Modern society has created a giant apparatus for the cultivation of the hard skills, while failing to develop the moral and emotional faculties down below. Children are coached on how to jump through a thousand scholastic hoops. Yet by far the most important decisions they will make are about whom to marry and whom to befriend, what to love and what to despise, and how to control impulses. On these matters, they are almost entirely on their own. We are good at talking about material incentives, but bad about talking about emotions and intuitions. We are good at teaching technical skills, but when it comes to the most important things, like character, we have almost nothing to say.

The book, like any true “classic” (and I am convinced this will be one), is deep and broad. It includes such gems as:

- “The food at their lunch was terrible, but the meal was wonderous.”

- “For example, six-month-old babies can spot the different facial features of different monkeys, even though, to adults, they all look the same.”

- In his high school, “…life was dominated by a universal struggle for admiration.”

- “The students divided into the inevitable cliques, and each clique had its own individual pattern of behavior.”

- “Fear of exclusion was his primary source of anxiety.”

- “Erica decided that in these neighborhoods you could never show weakness. You could never back down or compromise.”

- “In middle class country, children were raised to go to college. In poverty country they were not.”

- Jim Collins “…found that many of the best CEOs were not flamboyant visionaries. They were humble, self-effacing, diligent, and resolute souls who found one thing they were really good at and did it over and over again. They did not spend a lot of time on internal motivational campaigns. They demanded discipline and efficiency.”

- “Then a quiet voice could be heard from the other end of the table. ‘Leave her alone.’ It was her mother. The picnic table went silent.”

- “Erica resolved that she would always try to stand at the junction between two mental spaces. In organizations, she would try to stand at the junction of two departments, or fill in the gaps between departments.”

- “School asks students to be good at a range of subjects, but life asks people to find one passion that they will do forever.”

- “His missions had been clearly marked: get good grades, make the starting team, make adults happy. Ms. Taylor had introduced a new wrinkle into his life—a love of big ideas.”

- “…if Steve Jobs had come out with an iWife, they would have been married on launch day.”

- “Epistemological modesty is the knowledge of how little we know and can know.”

There are so many more gems of wisdom. For example, Brooks notes that in current culture there is a new phase of life. Most of today’s parents and grandparents grew up in a world with four life phases, including “childhood, adolescence, adulthood and old age.” Today’s young will experience at least six phases, Brooks suggests: childhood, adolescence, odyssey, adulthood, active retirement, and old age.

While many parents expect their 18- and 19-year-old children to go directly from adolescence to the adult life of leaving home and pursuing their own independent life and a marriage relationship, their children are surprising (and confusing) them by embracing their odyssey years: living at home, then wandering, then back home for a time, taking a long time to “play around” with their education before getting serious about preparing for a career, and in general enjoying their youthful freedom. Most parents are convinced they’re kids are wasting their lives when in fact this is the new normal.

The odyssey years actually make a lot of sense. The young “…want the security and stability adulthood brings, but they don’t want to settle into a daily grind. They don’t want to limit their spontaneity or put limits on their dreams.” Parents can support this slower pace with two thoughts: 1) the kids usually turn out better because they don’t force themselves to grow up too fast like earlier generations did, and 2) the parents get to enjoy a similar kind of relaxed state in the “active retirement phase.”

Most odysseys pursue life in what Brooks calls The Group—a small team of friends who help each other through this transition. Members of a Group talk a lot, play together, frequently engage entrepreneurial or work ventures with each other, and fill the role of traditional families during this time of transition. Even odysseys who live at home for a time usually spend much of their time with their Group.

This book is full of numerous other ideas, stories, studies, and commentaries. It is the kind of reading that you simply have to mark up with a highlighter on literally every page.

Whether you agree or disagree with the ideas in this book—or, hopefully, both—it is a great read. Not a good read, but a great one. Some social conservatives may dislike certain things such as the language used by some characters or the easy sexuality of some college students, and some liberals may question the realistic way characters refuse to accept every politically-correct viewpoint in society—but both are accurate portrayals of many people in our current culture.

The Social Animal may not remain on the classics list as long as Democracy in America, but it could. At the very least, it is as good a portrayal of modern society as Rousseau’s Emile was in its time. It provides a telling, accurate and profound snapshot of American life at the beginning of the 21st Century. Reading it will help modern Americans know themselves at a much deeper level.

This is a book about many things, including success and happiness as mentioned above. But it is also a classic book on freedom, and on how our society defines freedom in our time. As such, it is an invaluable source to any who care about the future of freedom. Read this book to see where we are, where we are headed, and how we need to change. The Social Animal is required reading for leaders in all sectors and for people from all political persuasions who want to see freedom flourish in the 21st century.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Blog &Book Reviews &Community &Culture &Current Events &Education &Entrepreneurship &Family &Generations &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Postmodernism &Service &Statesmanship &Tribes

Prodigal Politics

April 13th, 2011 // 8:25 am @ rachel

Right, Left, and Above

Sometimes the best political analysis is found in surprising places. For example, Timothy Keller’s excellent book The Prodigal God gives a deep and profound analysis of modern conservatism and liberalism–clearly and effectively showing the truth, as well as the glaring flaws, of each. James Redfield’s insightful book The Twelfth Insight does the same. Both are essential reading for anyone today who cares about the future of freedom.

Consider the following quotes from The Twelfth Insight:

Consider the following quotes from The Twelfth Insight:

Quote One: “I’m pretty sure the government will be declaring martial law pretty soon, and people need to be prepared. The first thing they’ll do is take up all the guns and many books.”

It was becoming pretty clear that I was talking to someone on the extreme Right politically.

“Wait a minute,” I said casually. “None of that can happen. There are constitutional safeguards.”

“Are you kidding?” he reacted. “One or two more Leftist judges, and that won’t be the case anymore. Things are out of control. The country we grew up in is being changed. We have to do something now. We think the Document is going to call for a real rebellion against the Leftists.”

“What?” I said forcefully. “I can’t see anyone getting the idea of rebellion from this Document–maybe a more enlightened Centrism. Have you read it?”….

“You better wake up,” one of them yelled. “You people on the Left are ruining this country, and we’re not going to stand for it much longer. We’d rather have the corporations take over than you idiots.”

Quote Two: “You’re one of those Right-wingers,” the loud man said, waving a finger at Coleman. “If you weren’t, you wouldn’t be talking like this.”

Coleman shook his head. “I’m only saying that it takes a balance. Some people want big government totally regulating everything and others want big corporate influence and very little regulation. I think the best position is right in the middle…”….

“Where are you going, Right-winger?” one of the other men shouted. “You aren’t going to win. If we have to install a dictator, we’ll do it. You aren’t going to win!”

Quote Three: This type of controlling is the chief characteristic of those both Left and Right, who have a primarily ideological approach to politics. They don’t want to debate the issues. They want only to shout down the opposition and win….

Both extremists were using the same tactic. If someone disagreed with them even slightly, they were simply pushed into the opposite extreme category–so they could be dismissed and dehumanized and not taken seriously. That way, each side–far Left and Right–could justify their own extreme behavior. Each thought of themselves as the good guys having to fight to save civilization from a soulless enemy….

“[C]ivility is the first thing that goes out the window. Those holding on to the old worldview often begin to cling to their obsessions with ever greater ferocity…”….

“The political Left and Right are both moving to the extreme because each thinks the threat is so great from the other side that extreme measures need to be taken. And of course, it’s all self-reinforcing.”

In addition to the competing views on the Right and Left, Redfield discusses those in the world who actually want conflict–for the benefit of their politics or positions of power. Hamilton discussed these same three groups in Federalist Paper number 1 (the effectual introduction to The Federalist).

A Parable for Our Time

One major problem with our contemporary politics was taught quite clearly two millennia ago in the parable of The Prodigal Son. The word “prodigal” means to be wasteful, which certainly applies to our modern government. In this parable, a father has two sons. The first son is obedient and orderly, follows the father and does what the father expects. The second son asks for his inheritance early, then spends it in riotous living.

When the inheritance is all spent, the second son comes crawling back to his father, begging to be a servant if he can just live at home and have food to eat and a place to sleep. The father throws a party, welcoming him home as a beloved son.

The elder son is livid. He sees even more of his own inheritance being spent on his wasteful brother, and he is hurt that his father never threw such a party for him–despite all his years of faithful obedience.

The climax of the parable comes when the reader asks this question: “Why did Jesus tell this story? What was his point?” Anyone who has read the parable clearly sees that the point is not to chastise the younger son, but the older. What does it all mean? Whatever your religion or beliefs, these are interesting and important questions.

Our modern politics fits very well within this parable. Conservatives believe in standards, responsibility, morals, conformity and in those who do these things reaping the benefits of their orthodoxy. Especially, they don’t want the father (government) taking their money to benefit those who haven’t taken care of themselves.

Liberals value the freedom to live as they see fit, pursue their own happiness their way, discover and seek and find themselves, not be tied down by dogmatic rules or outdated social customs, and they believe a higher authority (father/government) should always be there to help any who suffers.

That’s a conservative way of defining liberalism. But let’s consider it from a liberal perspective: The older brother was just plain mean. That’s often the problem with conservatism, or libertarianism, from the liberal view. The father used the elder son’s inheritance to take care of the younger son because he needed it–help, love, dignity, some basic human kindness and respect. Of course any loving father (or government) should do the same.

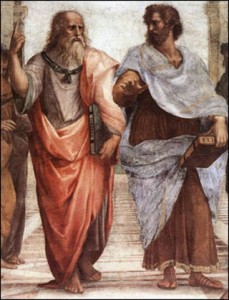

This is the old conservative-liberal argument, debated since Plato versus Aristotle. A person needs help. One side says: “Too bad, he did this to himself, he doesn’t deserve help, don’t help him. You really have no right to use my inheritance for him anyway! You might have the power, but it isn’t right!” The other view argues: “But as a loving father (government), we simply must help him. Don’t be so mean about it. Why are you so selfish anyway? We all simply must help the most vulnerable among us.”

The two sides frequently refuse to understand each other. They may say they understand, but then they launch immediately into a discussion of how their side is right and the other is wrong. They even call the other side “stupid” or “evil” for not understanding.

The True Elder Brother

What is missing in our current politics is what Keller calls “The True Elder Brother,” the other brother who isn’t depicted in the parable but is clearly meant to be there. As Keller put it: “This is what the elder brother in the parable should have done; this is what a true elder brother would have done. He would have said, `Father, my younger brother has been a fool, and now his life is in ruins. But I will go look for him and bring him home. [Note that this occurs before the younger brother even comes home on his own.] And if the inheritance is gone–as I expect–I’ll bring him back to the family at my expense.’ [Note: he doesn’t leave it to his father’s/government’s expense.]”

This is leadership. This is the example of a citizenry that handles things. “Poor, hungry, in need of education? We’ll help. We won’t ask government to do it. We will do it. Now. Without waiting, without questions. Somebody needs help? Here we are. Send us.” Or simply, “Give us your poor, your tired, your struggling masses yearning to be free . . .”

That’s what free people do. The old liberal argument (“government should use its power and force to fix the problems”) is as bad as the old conservative argument (“it’s their own fault, so too bad for them–let them suffer, or let someone help them, but don’t you dare make me help!”).

But free people act like free people. They see needs and they go to work helping. They don’t turn to government (they know that this is a bad use of force) and they don’t ignore the needs (they know that this is selfish and wrong). Such a society stays free, and if they ever stop being this way they know they will lose their freedoms. Indeed, they won’t even deserve to be free anymore.

The great question of freedom is, will the people govern or will they politic? Will they lead or snivel? If the first, they will spread freedom; if the second, their freedom will be lost.

Our Job as Citizens

Problems will arise. A free people handles them, leaving to the government only that which can only be done at the highest levels–like national security and fighting crime.

The problem is that in party politics, everything becomes about government. Liberals want government to fix everything, conservatives want the government to stick to national security, law enforcement, education and projects that benefit one’s own state. This becomes the ends and means of the whole debate. Meanwhile, who is helping those in need? And who is watching the government to make sure our freedoms remain strong?

Both of these jobs are the roles of the citizenry–not the government–in free nations. But when politics gets involved, we forget and ignore both. When this happens, freedom declines. The solution is simple: as citizens we must stop getting caught up in political issues and give our time to two things: helping those in need, and understanding and maintaining freedom. These are acts of governance, not politics. The one great act of politics we need to do is vote, and elections will be much more simple if the citizens are doing their two great governance roles!

So, let’s test ourselves. Are we deserving of the title of free people, or are we something else? Let’s find out. In your neighborhood:

- Several poor families need help

- Immigrants come looking to make a living

- The environment is being polluted

- Several minority families can’t afford college for their children

Do you call in the government? Many liberals and conservatives (along with many socialists and Democrats) would take this path. It is what the father did in the parable.

In contrast, do you comment on how these people should “get off their butts” and fix their lives, and then do nothing else? Then, when the government does something, do you throw up your hands in anger and frustration? Many conservatives and liberals (and many extreme conservatives, libertarians and Republicans) are with you in this choice.

Another option: Do you visit the families, make friends, offer the father a better job or get him an interview with a friend of yours, start a scholarship drive for the college-age kids, get together a service project to clean the polluted areas, etc.? These are the behaviors of people who deserve freedom.

“But the government won’t let us!” many will argue. “But if we do the work, they just won’t value it.” “But I’m too busy supporting my own family.” “But really fixing this would cost way too much.” “It’s their problem–why don’t they do it themselves.” “This really is a job for government, not for regular people.” But, but, but. These are not the words of the free. Governments can be negotiated with, projects can be structured to include the scholarship recipients, you can make time for freedom or lose it, concerns can be worked through. Free people figure out how to do things right and do the right things.

The True Citizen

I once taught a college course on the writings of the American founders, and during the semester we discussed broadly and deeply the proper role of government and the need for limitations on government. I invited a county sheriff, among others, to speak to the students. He discussed a number of issues of law enforcement, dealing with people, and local government, then he mentioned that he had just written a grant to buy clothes for kids living in trailer parks. The problem, he said, was that new kids moved into his cities, but since they were poor and could only afford one pair of pants they usually smelled bad to the “good” kids in school.

As a result, the only kids who would befriend them were those using drugs or excessive tobacco and alcohol. He was very excited about his grant, which he felt would help the “trailer-park kids” make “better” friends and stay off drugs.

I found myself thinking that the so-called “good” kids weren’t really all that good. By that time my class was harassing the man for using government to solve private problems and wasting the taxpayers’ money. I listened to their exchange for about twenty minutes. In truth, the students had a good technical understanding of the founders’ writings. They understood that not everything is best run by government. I was glad to see this. But I also found myself frustrated that they still didn’t quite get it.

Finally, the sheriff got frustrated himself and asked the class: “Okay, fine, I agree that private solutions would be better than government money. But how many of you are running a private program that would help these kids? I have seven kids who need a new pair of pants right now, today, and our research shows that this one thing will keep six of them off drugs. I’ve got the pants sizes in the car. Who can help me?”

We sat in the embarrassed silence as hardly anyone volunteered.

The sheriff shook his head in dismay and said nothing. Finally, abashed, one student said aloud, “I’m a student, I don’t have any extra money.” Then, to my amazement, another student said, “It’s just not right for government to use money that way.” Others chimed in, and the debate resumed.

Afterwards, a number of students pitched in their money to help, and this experience left us with lots to discuss in later class periods. But I never forgot how quick we are to be the younger brother, the older brother, or even the father, but how slow we are to be the true elder brother.

On another occasion at a formal event in a state capitol building my wife and I sat with a nationally recognized libertarian leader. We discussed a number of topics, but somehow toward the end of the event this man and my wife got on to the subject of libertarianism versus both conservatism and liberalism. When the man said libertarianism was the only hope for America’s future, my wife told him that she hoped not.

“Why?” he asked. She told him she thought conservatism, liberalism and libertarianism all had some good features and some real flaws, and that the great flaw in libertarianism is that it not only doesn’t want government to help needy people but that it seems to not want anybody to help them.

The man surprised us by trying to convince us that everybody in need got there themselves and deserves to be there, and that the only right thing to do is to leave them to their struggles. Period. When my wife gave up appealing to caring and later morality, and made a convincing case for the self-interest of charitable acts, the man angrily pulled out his wallet and said, “Fine. Just name a charity, and I’ll write you a check for it right now!” She immediately named one. He angrily shoved his wallet back into his pocket and stormed out of the room. We just looked at each other.

Certainly not all who consider themselves libertarians or far-Right have this view. But far too many people, whatever they call themselves politically, seem to adopt the ideas of the younger or the older prodigal brothers–when we should all be seeking to become the “true older brother.”

Younger brothers turn to the government, elder brothers angrily complain and bluster. Fathers (governments) take from the rich and give to the poor–after using up the majority of the money on administrative expenses. This is the world of politics. No wonder David Hume was so against political parties, and no wonder the founding generation agreed with him on this.

But “true elder brothers,” those who are free and think like the free, choose differently. They see needs and take action. They wisely think it through and do it the right way. They actually end up solving problems and changing the future for good. They are the true progressives–because they actually improve things. They are the true conservatives, because they conserve freedom, dignity and prosperity.

Conservatives most value responsibility, morality, strength, and national freedom, where liberals most highly prize open-mindedness, kindness, caring, fairness and individual freedom. The thing is, both lists are good. They don’t have to be in conflict. Indeed, both are the heritage we enjoy from past generations of free people who at their best valued and lived all of these together.

If conservatives, extreme conservatives and libertarians would all just be nicer, more caring and open, more tolerant and helpful, American freedom would increase. If liberals and progressives would all work to provide more personal service and voluntary solutions with less government red tape, we would see a lot more positive progress and change.

Freedom works, and we need to use it more. Less politics, more freedom. America needs this. When it is time to vote, we should fulfill this duty. Before and after the voting, we should fulfill the other vitally important roles of free citizens: build our communities and nations, support a strong government that accomplishes what governments should, study and truly understand freedom, keep an eye on government to make sure we maintain our freedoms, and voluntarily and consistently help all those in need.

**************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Blog &Book Reviews &Citizenship &Community &Culture &Family &Liberty &Postmodernism &Statesmanship &Tribes

The Most Important Thing

March 17th, 2011 // 1:15 am @ Oliver DeMille

My oldest daughter asked me recently, “What is the most important thing Americans need to know right now about freedom?”

I didn’t even have to think about the answer, it is so clear to me.

My purpose here is to share the single most important thing the people need to know about freedom.

I have shared this idea before, but since it is the most important thing, in my opinion, it bears repeating.

On many occasions I have asked advanced graduate students or executives to diagram the American government model which established unprecedented levels of freedom and prosperity to people from all backgrounds, classes and views.

They always do it in the wrong order, and they get the most important part wrong.

Specifically, they start by diagramming three branches of government, a judicial and an executive and a bicameral legislature, and then they sit down.

They think they’ve done the assignment.

When I ask, “What about the rest?” they are stumped for a few seconds.

Then some of them have an epiphany and quickly return to the white board to diagram the same thing at the state level.

This time they are sure they are done.

“What level of government came first in the American colonies?” I ask. After some debate, they agree that many towns, cities, counties and local governments were established, most with written constitutions, for over two centuries before the U.S. Constitution and many decades before the state governments and constitutions.

“So, diagram the founding model of local government,” I say.

They then set out to diagram a copy of the three-branch U.S. Constitutional model.

Nope.

This sad deficit of knowledge indicates at least one thing: Americans who have learned about our constitutional model have tended to learn it largely by rote, without truly understanding the foundational principles of freedom.

We know about the three branches, the checks and balances, and we consider this the American political legacy.

But few Americans today understand the principles and deeper concepts behind the three branches, checks and balances.

The first constitutions and governments in America were local, and there were hundreds of them.

These documents were the basis of later state constitutions, and they were also the models in which early Americans learned to actively govern themselves.

Without them, the state constitutions could never have been written. Without these local and state constitutions, the U.S. Constitution would have been very, very different.

In short, these local constitutions and governments were, and are, the basis of American freedoms and the whole system.

The surprising thing, at least to many moderns, is that these local constitutions were very different than the state and federal constitutional model. There were some similarities, but the structure was drastically different.

The principles of freedom are applied differently to be effective at local and tribal levels.

A society that doesn’t understand this is unlikely to stay free. Indeed, history is exact on this point.

Another surprise is that nearly all the early townships and cities in the Americas adopted a very similar constitutional structure.

They were amazingly alike. This is because they are designed to apply the best principles of freedom to the local and tribal levels.

And there is more.

This similar model was followed by the Iroquois League as well, and by several other First Nation tribal governments.

Many people have heard this, but few can explain the details of how local free governments were established.

This same model of free local/tribal government shows up in tribes throughout Central and South America, Oceana, Africa, Asia and the historic Germanic tribes including the Anglo Saxons.

Indeed, it is found in the Bible as followed by the Tribes of Israel. This is where the American founders said they found it

The most accurate way, then, to diagram the American governmental system is to diagram the local system correctly, then the state and federal levels with their three branches each, separations of power and checks and balances.

But how exactly does one diagram the local level?

The basics are as follows: The true freedom system includes establishing as the most basic unit of society—above the family—small government councils that are small enough to include all adults in the decision-making meetings for major choices.

This system is clearly described in Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, Volume 1, Chapter 5,[i] and in Liberty Fund’s Colonial Origins of the American Constitutions.

It is also portrayed in the classic television series Little House on the Prairie and in many books like Moody’s Little Britches, Stratton-Porter’s Laddie and James Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans.

In fact, if you know to look for it, it shows up throughout much of human history.

These adult town, city or tribal councils truly establish and maintain freedom by including in the most local and foundational decisions the voices and votes of all the adult citizenry.

These councils make decisions by majority vote after open discussion. They also appoint mayors/chiefs, law enforcement leaders, judges and other personnel.

All of these officials report directly to the full council of all adults and can be removed by the council.

Where representative houses and offices are much more effective at the larger state and national levels, the whole system breaks down if the regular citizens aren’t actively involved in governance at the most local levels.

In this model, every adult citizen is officially a government official, with the result that all citizens study the government system, their role in it, the issues and laws and cases, and think like leaders.

They learn leadership by leading.

Without this participatory government system at the local levels, as history has shown, freedom is eventually lost in all societies.

Once again, the most successful tribes, communities and even nations throughout history have adopted this model of local governance which includes all citizens in the basic local decision making.

The result, in every society on record,[ii] has always been increased freedom and prosperity.

No free society in recorded history has maintained its great freedom once this system eroded.

Tocqueville called this system of local citizen governance “the” most important piece of America’s freedom model.[iii]

Indeed, the U.S. Constitution is what it is because of the understanding the American people gained from long participation in local government councils.

These were the basis of state constitutions and the federal Constitution. If we don’t understand the local councils, we don’t understand the Constitution or freedom.

Today we need a citizenship that truly understands freedom, not just patriotic, loyal or highly professional people. This is the most important thing modern Americans can know if we want to maintain our freedom and widespread prosperity.

Endnotes:

[i] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (from the Henry Reeve text as revised by Francis Bowen, edited by Phillips Bradley, and published by Alfred A. Knopf).

[ii] See the writings of Arnold Toynbee and the multi-volume writings of Will & Ariel Durant.

[iii] Op cit., Tocqueville.

Category : Community &Culture &Government &Liberty &Tribes

The Education Crossroads

November 12th, 2010 // 5:18 am @ Oliver DeMille

Education today is at a crossroads, and the options are fascinating.

Certainly the rise of the Internet has revolutionized most industries, and its impact on education is expected to be significant. But the change in technology isn’t the only major shift which is impacting schooling.

The end of the Cold War ushered in a new era of world politics — and of course, politics always impacts education.

Also, economic struggles have caused nations to put a premium on expenses, with the result that education is being asked to meet higher standards in order to justify its cost.

All of this would seem to indicate the need for broader, more inclusive and expansive education, with a focus on quality teaching and increased excellence.

Instead, these three trends have combined to create a surprising result.

Where increased Internet connections at first promised to bring more understanding, tolerance and cooperation between groups, the opposite has too often occurred.

Though we have the world at our online fingertips and the ability to interact directly with those of differing views, ideas and values, too many people are joining cliques that promote a narrow mindset and exclude and mistrust all others. The defensive posture occasioned by economic challenges and world events seems to increase this tendency.

Where is the Melting Pot?

The 18th and 19th century ideal of a melting pot doesn’t seem to be spreading enough online. In the 1970s it sort of evolved into the salad bowl idea, where differences were welcome as we all mixed together in a single serving.

Now we’re lucky if the clans in society agree to occupy a separate station at the same smorgasbord.

The danger to freedom is significant, maybe even extreme. James Madison taught in Federalist 10 that numerous factions would benefit freedom by keeping any one or two groups from becoming too powerful.

All decent groups would have a say in the world in this model, Madison argued. This benefit still remains in the Internet era.

But Madison also argued that people would come together when great cooperation was needed, that people and groups would put aside differences and collaborate on the important things.

Unfortunately, this powerful cultural model is unraveling in our time.

The reason is simple: As people increase their connections with those who agree with them on most things, they begin to fall into groupthink, a malady where most of those you communicate with agree with you on most things and disagree with you on little. Each member of the group learns how to more effectively argue the clique’s talking points, and nearly everyone stops listening to other points of view.

From Madison’s day until the Internet age, such natural bonding with groups was always tempered by geography. No matter how hard people tried to interact only with like thinkers, no matter how hard they worked to keep their children free from diverse views, neighbors nearly always ruined this utopian scheme.

The debate, the discussion, the conversations amongst diverse peoples all living in a free society — these helped individual citizens become deep thinkers and wise voters, and it helped ensure that negative traditions slowly were replaced with better ones. Without such progress, no free society can retain its freedoms.

But in the virtual age, no such checks or balances are in place. Youth and adults in all educational models and work environments are able to avoid deep conversations about important topics like politics, beliefs and principles with all who disagree with them.

This is facilitating a clique mentality. Social networks, email, cell phones and the other emerging technologies all strengthen this trend away from diverse and connected communities and toward homogenous and exclusive cliques.

The problem is that such cliques are by their very nature arrogant, overly sure of their own correctness on nearly everything, and vocally and even angrily opposed to pretty much everyone outside of their own clique.

Unfortunately, they too often spend a great deal of energy and effort demeaning other people, groups and ideas. Such cliques typically refuse to admit their own weaknesses while they label and vilify “outsiders.”

On the positive side, this is one reason there are now more independents than either Democrats or Republicans: a lot of people just got tired of too much hyper-partisan rhetoric.

But this problem goes far beyond politics, and impacts nearly every segment of our society. It is like adopting Elementary or High School culture among the adults in our world.

Dangerous Cliques

Since education is always an outgrowth of society, this trend is a major concern. The rebirth of tribes in our time, many of them online tribes made up of people who find common ground and like to work together, is the positive side of this same trend.

Indeed, using technology to interact and connect with people you like and learn with is certainly constructive. Leaders are needed to help increase the positive melting pot on line and in social networks.

Hopefully this will continue to grow. But its negative counterfeit is an increasing problem.

A first step in dealing with the growing “High School-ization” of our adult society is to simply identify the difference between the positive New Tribes and the opposing trend of growing cliques:

| New Tribes | Cliques |

| Tolerant, Inclusive, Friendly | Intolerant, Arrogant, Exclusive |

| Respectful of Other Views | Angry and Overly Critical of Other Views |

| Market by Helping You Find the Best Fit for You, From Them or Their Competitors | Market by Tearing Down Competitors to Build Themselves |

| Respect Your Ability to Make the Best Choices for You | Act As If You Need Their Expertise to Succeed and Will Fail Without Them |

| Offer to Help You Meet Your Needs | Try to Convince or Sell You to Act “Now” in the Way They Want, or You’ll Fail |

In short, the positive New Tribes offer you more freedom, empower you, and give you opportunities and options in a respectful and abundant way, while the clique mentality thinks it must “sell” you, convince you, and tear down the competition.

The New Tribes are relaxed, supportive and open, while cliques are closed, scarcity-minded and disrespectful of the competition and all “others.”

Ruining the Game

When my son was young he wanted to join a sports team, so I took him to watch a number of sports in progress. He ended up engaging karate, which became a long-term interest in his life.

During the visits to various sports venues, he witnessed an angry father at a little league baseball game. While most of the parents in attendance probably hoped their child would win, they seemed to find value in the game regardless of wins and losses; they apparently felt that the game was a positive experience for all the kids — for other children as well as their own.

One man took a different approach. He yelled and swore at each umpires’ calls that went against his child. He quite vocally demonized the other team and the other team’s coach. He stood behind the backstop when the other team was pitching and tried in many ways to distract the opposing pitcher.

He went after this 10-year-old pitcher from the other team like he actually wanted to hurt him. The boy’s coach had to go reassure the pitcher several times. I don’t know if the boy was afraid of the angry man, but he looked like it.

Most of the parents in the crowd were upset with this man, but they remained polite. After about 30 minutes of this, my eight-year-old son asked if we could leave. He was uncomfortable with the situation even as a mere spectator.

He never asked to go back to a baseball game, and we didn’t stay long enough to see if anything was done to help this man calm down. From the conversations in the crowd, it was clear that the man did this at every game.

I do believe that this man cared for his son and wanted to help him. He may have had many good intentions, and he certainly had some positive intentions. But he acted in the clique mentality. He did it without respect or proper boundaries.

(A new thought: I’m pretty sure he soured my son to playing baseball, but only now as I write this does it occur to me that maybe he also helped interest my son in karate for his own defense!)

A High-School-ization of Society

If you are this kind of a sports parent (or sports fan in high school, college or professional sports), you know who you are.

But do we not also see these clique behaviors too often in business, work, politics and even education?

Clearly the impact on education is significant. More to the point, the future of education can’t avoid being impacted by the High School-ization of culture.

Cliques are negative in many ways. And: they are just plain mean. They can do lasting damage even among youth; so imagine their potential impact when adopted by a significant and increasing number of adults of our society.

In short: the Cold War is over and we tend to look for enemies within rather than outside of our own nation; economic struggles of the past years have made most people less tolerant and more self-centered and even scared; and the technology of the day has made it easier than ever to connect with and only listen to a few people who tend to agree with us on almost everything.

The result is more frustration, anxiety, and anger with others. More people are thinking in terms of “us versus them,” and most of our society has stopped really listening to others.

Unless these tendencies change, things will only get worse. The future of education is closely connected with these trends, tendencies and perspectives.

In politics, the response to these challenges has been the rise of the independents. In business, it has been a growing rebirth of entrepreneurship.

And in marketing, it has been a focus on Tribes as the new key to sales. But in education, no clear solutions have yet arisen. I propose the principles of Leadership Education as part of the answer.

Modern versus Shakespearean Mindsets

The great classical writer Virgil provides some insight into the challenge ahead for education. In our day we tend to see the world as prose versus poetry. Some might call this same split the left brain versus the right brain, science versus art, or logic versus creativity.

Using this modern view of things, some educational thinkers see the future of education as the continuing split between the test-oriented public and traditional private schools versus the eclectic personalization of charter, the new private and home schooling movements.

Or we may see the intermixing of these two models as traditional schools become more creative and new-fangled education becomes more test-focused.

In an earlier age, the Shakespearean world tended to divide learning into three categories: comedies, tragedies and satires.

Comedies show regular people working in regular circumstances and finding love or happiness in regular life.

Tragedies pit people against drastic challenges that test them beyond their limits and bring major changes to their lives and even the world.

Satires emphasize the futility of our actions and show us the power of fate, destiny and other things we supposedly cannot control.

Applying this mindset, one would expect to see a future of education with all three outcomes. Comedic approaches to education try to make sure everyone gets basic literacy and that all schools meet minimum standards. No child can be left behind in this education for the regular people — and we’re all regular people.

In contrast, some will seek for a truly great education and to make a great difference in the world. If they fail, the tragedy is the loss of their potential greatness to the world. If they succeed, the world will greatly benefit from their leadership, contributions and examples.

All education should be great, this view maintains, and all people have potential greatness within. If I thought the Shakespearean worldview was driving our future, I would be of this view.

A satirical stance would argue that some people will get a poor education and yet do great things in their careers and family. Others, according to this view, will get a superb education and then either fail to accomplish much of anything or do many bad things with their knowledge.

Education has little correlation with life, the satirist maintains. Fund education better, or don’t; increase standards, or not; emphasize learning or just ignore it—none of this matters much in the satirical view. A few will rise, a few will fall, most will stay in the middle, and education will have little to do with any of this.

I disagree with this perspective, and I believe that history is proof of its inaccuracy. There are, of course, a few exceptions to any system, model or rule; but for the most part a quality educational model has a huge impact on the freedom and prosperity of society.

But I do not believe that either the modern or the Shakespearean mindsets will influence our future as much as that from and even earlier age — the era of Virgil.

But I do not believe that either the modern or the Shakespearean mindsets will influence our future as much as that from and even earlier age — the era of Virgil.

I am convinced that Virgil’s understanding of freedom eclipses both of these others. Virgil witnessed Rome losing many of its freedoms, and he saw how the educational system had a direct impact on this loss.

In the Virgilian model, education is not modeled on the conflict between left and right brains nor on the battles and interplay between comedy, tragedy and satire.

Instead, he saw learning as the interactions of the epic, the dialectic, the dramatic, and the lyric.

In our post-Cold-War, Internet-Age, financially challenging world, our learning is deeply connected with all four of these.

Epic education means learning from the great(est) stories of humanity in all fields of human history and endeavor, from the arts and sciences to government and history to leadership and entrepreneurship to family and relationships, and on and on.

By seeing how the great men and women of humanity chose, struggled, succeeded and failed, we gain a superb epic education. We learn what really matters.

The epics include all the greats — from the great scriptures of world religions to the great classics of philosophy, history, mathematics, art, music, etc.

Epic education focuses on the great classic works of mankind from all cultures and in all fields of learning.

Dialectic education uses the dialogues of mankind, the greatest and most important conversations of history and modern times. This includes biographies, original writings and documents that have made the most difference in the world. It is also very practical and includes on-the-job style learning.

Again, this tradition of learning pulls from all cultures and all fields of knowledge.

It especially focuses on areas (from wars and negotiations to courts of law and disputing scientists, to arguing preachers and the work of artists, etc.) where debating sides and conflicting opponents gave rise to a newly synthesized outcome and taught humanity more than any one side could have without opposition. Most of the professions use the Dialectic learning method.

Dramatic learning is that which we watch. This includes anything we experience in dramatic form, from cinema and movies to television and YouTube to plays, reality TV programs, etc.

In our day this has many venues—unlike the one or two dramatic forms of learning available in Virgil’s time. There is a great deal to learn from drama in its many classic, modern and post-modern modalities.

Lyric education is that which is accompanied by music, which has a significant impact on the depth and quality of how we learn. It was originally named for the Lyre, a musical instrument that was used for musical accompaniment during a play, or with poetic or prose reading.

Some educational systems still use “classical” (especially Baroque) and other types of music to increase student learning of languages, memorized facts and even science and math.

And, of course, most Dramatic (media) learning is presented with music.

Epic Freedom

With all this as background, I think the future of education is very much in debate. My reasons for addressing this are:

- It appears that far too few people are engaged in the current discussion that will determine the future of education.

- Even most who are part of the discussion are hung up on things like public versus private schools, funding, testing, left versus right brain, minimum standards for all (comedic) versus the offer of great education for most (to avoid tragedy), teacher training, regulations, policy, elections, etc.

- I know of very few people considering the future of education from its deepest (what I’m calling Virgil’s) level.

Specifically, our current technology has changed nearly everything regarding education, meaning that in the Internet Age the cultural impact of the Dramatic and Lyric styles of learning over the other types threaten to undo American freedom.

In short, freedom in any society depends on the education of the citizens, and when the Epic and Dialectic disappear, freedom soon follows.

And make no mistake: The Epic and Dialectic models of learning are everywhere under attack. They are attacked by the political Left as elitist and contrary to social justice; they are attacked by the political Right as useless for one’s career advancement.

They are attacked by the techies as old, outdated and at best quaint. They are attacked by the professions as “worthless general ed. courses,” and by too many educational institutions as “irrelevant to getting a job.”

But most of all (and this is far and away their most lethal enemy) they are supplanted by the simple popularity and glitz of the Dramatic and Lyric.

I do not believe that the Dramatic, Lyric and other parts of the entertainment industry have an explicit agenda to hurt education or freedom—far from it. They bask in a free economy that buys their products and glorifies their presenters.

Nor are Dramatic and Lyric products void of educational content or even excellence. Many movies, television programs, musical offerings and online sites deliver fabulous educational value.

Songs and movies, in fact, teach some of the most important lessons in our society and many teach them with elegance, quality and integrity.

But with all the good the Dramatic and Lyric styles of learning bring to society, the reality is that both free and enslaved societies in history have had Dramatic and Lyric learning.

In contrast, no society where the populace is sparsely educated in the Epics has ever remained free. Period. No exceptions.

And in the freest nations of history (e.g. Golden Age Greece, the Golden Age of the Roman Republic, the height of Ancient Israel, the Saracens, the Swiss vales, the Anglo-Saxon and Frank golden ages, and the first two centuries of the United States, among others), both the Epic and Dialectic styles of learning have been deep and widespread among the citizenship of the nation.

If we want to remain a free society, we must resurrect the use of Epic education in our nation.

Six Futures

Using Virgil’s models of learning as a standard, I am convinced that we are now choosing between six possible futures for our societal education—and freedom. Our choice, at the deepest level of education, is to select one of the six following options (or something very much like them):

I. Epic Only.

Since all societies adopt Dramatic and Lyric methods of learning, this model would make Epic education official in academic institutions and leave the Dramatic and Lyric teaching to the artists. Such a model is highly unlikely in a world where career seriously matters and has only been applied historically in slave cultures with strong upper classes.

(Theoretically, this model might be offered to all citizens in society instead of the more elitist model of history. But without career preparation, some in the lower and middle classes would be lacking in opportunity regardless of the quality of their Epic education.) This model is very bad for prosperity and freedom.

II. Dialectic Only.

Again, such a society would have non-school Dramatic and Lyric offerings and schools would emphasize career training, job preparation, and basic skills for one’s professional path.

Business, leadership and politics would be run by trained experts and citizens would have little say in governance. Like the aristocracies of history, this model is not friendly to freedom — though it can support prosperity for a short time.

III. Dramatic and Lyric Only.

Only tribal societies have adopted such a model, and they were easily conquered by enemies and marauders. This model is not good for prosperity or freedom.

IV. Epic and Dialectic Together.

Again, the Dramatic and Lyric would still be part of the society but not a great part of the schools. Unfortunately, without the Dramatic and Lyric taught together with the Epic and Dialectic, the Epic is greatly weakened.

Societies which have tried this, like modern Europe and North America, have seen the Epic greatly weakened and the Dialectic take over nearly all education. This is bad for freedom and long-term prosperity.

V. All Four Types as Separate Specialties.

In this model, young students would receive only a basic broad education and would focus on a specialty early on. Each type of learning could be very well developed, but each person would only be an expert in one (or, rarely, two).

This was attempted by many nations in Western Europe, and to a lesser extent Canada and the U.S., since World War II. The results were predictable: freedom and prosperity suffered for all but the most wealthy (who got interconnected Epic, Dialectic, Dramatic and Lyric education in private schools).

VI. All Four Types as Interconnected Learning.

This combines great Epic, Dialectic, Dramatic and Lyric learning together—for nearly all students in society.

Moreover, all four options are available to all students in public schools and the laws also allow for numerous private, home and other non-traditional options with parents as the decision makers.

An additional natural effect of this system is that the adult citizens of society are deeply involved in learning throughout their lives — using all four types of learning and applying all knowledge to their roles as citizens and leaders. This model has been the most beneficial to prosperity and freedom throughout history.

The choice between these types of education is being made today. During the Cold War, especially after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik in 1957, American leaders determined to de-emphasize Epic education and focus on the Dialectic.

Then they further weakened this choice by dumbing down the textbooks and workbooks when they removed much of the actual dialogues which formed the basis of each field of human knowledge.

Later, facing the increasing popularity of career-focused schooling, states and school boards took much of the Dramatic and Lyric out of the schools. Indeed, the last two generations of students were mostly educated in a shallow version of the Dialectic Only.

The consequence to freedom has been consistently negative for at least four decades. It has also widened the gap between “the rich” and “the rest” and reduced general economic opportunity.

Today, we must make the choice to resurrect truly quality education. If we make the right choice, we will see education and freedom flourish. If not, we will witness the decline of both. Indeed, we simply must make the right choice.

We must also realize that this is not a choice for the experts. If the educational or political experts make this choice alone, it will mean that the people as a whole have not chosen to be educated as free citizens.

We must all do better in studying all four styles of learning, and in engaging the technology of our day to learn from diverse views and spread important ideas far and wide — to all groups and people, not just some narrow clique.

It is time for a new type of citizen to arise and earn our freedoms. As Virgil put it long ago:

Now the last age…

Has come and gone, and the majestic roll

Of circling centuries begins anew;

Justice returns…

With a new breed of men sent down from heaven…

Assume thy greatness, for the time draws nigh

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is the founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

He is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Community &Culture &Education &Family &Featured &Foreign Affairs &Generations &History &Leadership &Tribes

Types of Tribes

October 6th, 2010 // 4:00 am @ Oliver DeMille

NEARLY ALL OF THE WEAKNESSES I listed here are found in many traditional tribal cultures.

In our day new kinds of tribes are emerging with huge potential influence, power and popularity.

Indeed, the 21st Century may be the era where tribes become the most influential institutions in the world.

The trends are already in play, and nearly every major institution, nation and civilization is now made up of many tribes.

In fact, more people may be more loyal to their closest tribes now than to any other entity.

There are many types of tribes in the history of the world. A generic overview will obviously have its flaw and limitations—as will any inductive study, from personality typing to weather forecasting.

But with the necessary disclaimers and apologies, we can still learn much from the generalizations as we seek lessons to apply to ourselves.

There are several significant types of tribes in history, including:

- Foraging Tribes

- Nomadic Tribes

- Horticultural Tribes

- Agrarian Tribes (communities)

- Industrial Tribes

- Informational Tribes

Each is very different, and it is helpful to understand both the similarities and unique features of these types of tribes.

Note that the fundamental connecting factor which kept these tribes together was their means of production and their definition of wealth.

Families usually sacrificed to benefit the means of production. On a spiritual/emotional level, one way to define a tribe is a group of people who are invested in each other and help each other on an ongoing basis.

All these types of tribes meet this definition.

Level One Tribes: Everyone Knows Everyone

First, Foraging Tribes were usually established by family ties—sometimes, small family groupings and in other cases, larger groups with more extended family members. In marriage a person often left the tribe to join a new tribe.

Foraging tribes lived by gathering and hunting together. Their central means of production were legs: the ability to go out and find food for the family.

Children were the greatest source of wealth because they grew and provided more legs to the tribe.

These tribes were often female-centric, and their gods were fertility goddesses and earth goddesses who provided bounty of food.

Nomadic Tribes hunted and gathered, but also pillaged in order to survive and prosper. They traveled, some within a set area and a few more widely ranging.

They were nearly all herding societies, using animals to enhance their ability to hunt, gather and pillage. Their means of production was their speed, provided by great runners or herd animals.

They usually traveled in larger groups than Foragers, and intermarried within the tribe or from spouses taken during raids. Marriage meant joining the tribe of your spouse.

Nomadic Tribes were usually dominated by males and often practiced plural marriages. Herds were the central measure of wealth.

Third, Horticultural Tribes planted with sticks, hoes or hands, and tended crops to supplement food obtained by hunting.

Because hoes and sticks can be wielded equally by men and women, these tribes were often female-centric. Men hunted and women planted and harvested, bringing an equality to production.

Hands were the central means of production, used either in hunting or planting. Children were a measure of wealth, and deity was often a goddess of bounty.

These first three types of tribes make up the first level of tribal cultures, where nearly all tribe members worked each day to feed themselves and the tribe.

In the second level, specialization created free time for many to work on matters that have little to do with sustenance—from education to technology to arts and craftsmanship, and even extending into higher thinking of mathematics, logic and philosophy.

Level 2 Tribes

Agrarian Tribes began, as Ken Wilber describes it, when we stopped planting with sticks and hoes and turned to plows drawn by beasts of burden.

The change is significant in at least two major ways: First, pregnant women can plant, tend and harvest with sticks and hoes, but often not with plows, cattle and horses. That is, in the latter many pregnant women were in greater danger of miscarriage.

In short, in Agrarian society farming became man’s work. This changed nearly everything, since men now had a monopoly on food production and women became valued mostly for reproduction.

This was further influenced by the second major change to the Agrarian Age, which was that plows and animal power produced enough surplus that not everyone had to work to eat.

As a result, tradesmen, artists and scholars arose, as did professional tax-collectors, politicians (tax-spenders), clergymen and warriors.

Before the Agrarian Revolution, clergy and politicians and warriors had nearly all been the citizen-farmers-hunters themselves.

With this change came class systems, lords and ladies, kings and feudal rulers, and larger communities, city-states and nations.

The store of wealth and central means of production was land, and instead of using whatever land was needed, the system changed to professional surveys, deeds, licenses and other government controls.

Family traditions were also altered, as farmers found that food was scarce after lords and kings took their share.

Men were allowed one wife, though the wealthy often kept as many mistresses as their status allowed. Families had fewer children in order to give more land, titles and opportunity to the eldest.

Traditions of Agrarian Tribes, Communities and Nations are surprisingly similar in Europe, Asia, the Middle East and many colonies around the world.

While small Agrarian communities and locales often followed basic tribal traditions, larger cities and nations became truly National rather than tribal.

The fundamental difference between the two is that in tribes nearly all the individuals work together frequently on the same goals and build tight bonds of love and care for each other, while in nations there is much shared history and common goals but few people know each other or work together regularly.

As society nationalized, most people still lived and loved in tribal-sized communities.

Whether the ethnic communities of European cities, the farming villages of the frontier, church units of a few hundred who worshiped but also bonded together throughout the week, or so many other examples, most people during the Agrarian Age were loyal to national government but much more closely bonded with members of a local community.

When life brought difficulties or challenges, it was these community tribal members that could be counted on to help, comfort, commiserate, or just roll up their sleeves and go to work fixing their neighbors’ problems.

Community was also where people turned for fun and entertainment.

For example, one great study compared the way people in mid-century Chicago watched baseball games, attended cookouts and nearly always went bowling in groups, to the 1990s where most Americans were more likely to watch a game on TV, grill alone and go bowling alone or with a non-family friend.

Level 3 Tribes

Indeed, by the 1990s America was deeply into the Industrial Age.

Industrial tribes (no longer really Tribes, but rather tribes, small “t”) were built around career. People left the farms, and the communities which connected them, for economic opportunities in the cities and suburbs.

Some ethnicities, churches and even gangs maintained community-type tribes, but most people joined a different kind of tribe: in the workplace.

The means of production and measure of wealth in Industrial tribes was capital. The more capital you could get invested, the better your tribe fared (at least for a while) versus other tribes.

Competition was the name of the game. Higher capital investment meant better paychecks and perks, more job security, and a brighter future—or so the theory went.

While it lasted, this system was good for those who turned professional education into a lucrative career.

With level three came new rules of tribe membership. For example, individuals in industrial societies were able and even encouraged to join multiple tribes.

Where this had been possible in Agrarian communities, nearly everyone still enjoyed a central or main community connection.

But in the Industrial era, everyone joined long lists of tribes. In addition to your work colleagues, Industrial professionals also had alma-maters, lunch clubs like the Kiwanis or Rotarians, professional associations like the AMA or ABA or one of the many others, and so on.

With your kids in soccer, you became part of a tribe with other team parents; same with the boy scouts and girls clubs.

Your tribes probably included a community fundraiser club, donors to the post office Christmas food drive, PTA or home school co-op (or both), church committees, car pool group, racquetball partners, biking team, local theatre, the kids’ choir, lunch with your friends, Cubs or Yankees fans, and the list goes on and on and on.

In level three, the more tribes the better!

The two major tribes that nearly everybody joined in Industrial society were work tribes and tribes of friends.

Between these two, little time was left for much besides work and entertainment.

But make no mistake, the guiding force in such a society, the central tribe which all the others were required to give way for, was making the paycheck.

Families moved, children’s lives conformed, marriages sacrificed, and friends changed if one’s work demanded it. It was not always so, and this morality defined Industrial Age culture.

One big downside to Paycheck Tribes is that they cared about your work but not so much about you. Indeed, this is one of the main reasons why Industrial tribes weren’t really even tribes.

The other major reason is that you had only a few close friends and most people didn’t truly count on any non-family group or neighborhood or community to really be there for you when you needed it.