Jefferson Madison Debates: John Adams on How to Fix Washington D.C. in 1791 and 2018

June 28th, 2018 // 7:26 pm @ Oliver DeMille

“Odd, that so many should favor frames that seemed to be trying to outdo the art they held.”

~Brandon Sanderson, The Alloy of Law

What You Think You See

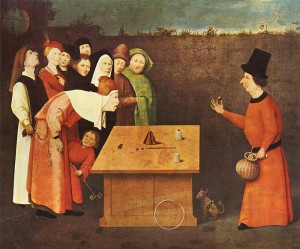

In the old American West, a façade town featured two- and sometimes three-story buildings lining Main Street, so visitors to the town would be impressed with how up-and-coming the community must be.

In the old American West, a façade town featured two- and sometimes three-story buildings lining Main Street, so visitors to the town would be impressed with how up-and-coming the community must be.

But when a person walked around to the side and back of the buildings, it turns out they’d find mostly one-story structures—sometimes little better than shacks or huts.

A few were even a façade built on the front of a rickety lean-to.

Some were respectable buildings, but they were usually made of adobe or pine rather than the fine hardwood edifices promised by their Main Street facades.

And, as I mentioned, they were only one story tall despite their appearance from the front.

Indeed, the only purpose of the two- or three-story façade was to impress.

In modern times, the idea that perception is reality has reached the level of myth.

To Conform or Not To Conform

It is taught in various circles as unquestioned truth, parroted in movies and television programs as a lasting principle, and often used to scold would-be individualists into working harder to conform and fit in.

“We must impress others to get ahead in the world,” the common wisdom seems to assure us.

C.S. Lewis lambasted this view in his classic, “The Inner Ring.”

If you spend your life trying to impress and fit in, as almost everyone does, he warned, you’ll waste a lot of time and energy and miss many of the important things that really matter in life.

Moreover, he predicted, you’ll fail to appeal to the only real society of substance, the other people who ignore trying to impress and fit in and instead set about doing good things in the world without worrying what others think.

He called this group the true inner ring, whose motto was something along the lines of “perception is merely perception—truth, reality, integrity and quality are what matter.”

John Adams wrote about this topic in his little-known and seldom-read classic, Discourses on Davila, which may be his best book next to Defence of the Constitutions of the United States (in fact, he referred to Davila as the fourth volume of Defence).

He said that nearly every person is plagued by a debilitating desire to be esteemed by others, to impress and fit in, to be admired, and that this is the basis of many human flaws including jealousy, envy, ambition, vanity, hatred, revenge, pride, and most human pain.

These are Adams’ specific words.

Adams said this desire for admiration is as real as hunger, and the cause of more suffering, anxiety, stress and disappointment than famine.

In contrast, the really good things in life, including virtue, nobility, honor, loyalty, wisdom, service, strength and so on, may or may not increase the admiration of others, but are often valued only to the extent that they do.

Competing for Mediocrity

Sadly, many people seek these things only if, and to the degree that, they increase admiration from others.

Far too many things are sought by mankind only because they attract “attention, consideration, and congratulations…” Adams said.

Likewise, too many good and important things are not pursued by many people because they do nothing to boost one’s status or station.

By the way, the point of Adams’ book on Davila is to show that because of basic human nature—built on this inner drive of nearly all men and women to rise in station, and not just to rise, but to rise above other people—there will always be conflicts in human societies and institutions.

His solution was to create separate branches of power, and to set up the government so these branches could check and balance each other in a way that no one government entity could become too powerful.

The result, he said, would be that the people in the nation would be able to live free of overreaching government.

In the process of making this argument he spends a great deal of time showing that this drive to fit in, impress, and in fact outdo other people (by being more impressive and fitting in better than them), was a serious obstacle to human happiness in families, schools, business and all facets of society.

When people become more knowledgeable and learned, for example, they tend to engage in more, not less, conflict with other learned persons.

He was not talking of debate, but of serious conflict.

Thus our schools and great universities, which could be the salvation of society in many ways, are distracted from their potential because their leading inhabitants are constantly striving for Reputation, Notoriety, and Celebration.

These three words are those used by Adams, which he capitalized for emphasis in his book.

Likewise, Adams laments, our branches of government are unable to truly lead because those who should be our best hope for great progress immediately, upon being elected or appointed to office, set out to compete with all other officials for more Fame, Glory, Reputation and Credit.

Again, these are Adams’ words.

Growing or Shrinking

Voters send representatives, presidents and others to do their will, to improve things, but the real work of most men and women lifted to leadership is to win this contest with each other.

“Improve the Nation, or Impress the Nation. That is the question.”

And the drive to impress nearly always wins the day.

Adams wrote of humanity’s so-called honors in withering terms:

“What is it that bewitches mankind to marks and signs? A ribbon? a garter? a star? a golden key? a marshall’s staff? or a white hickory stick?”

He is mocking us now.

“Though there is in such frivolities as these neither profit nor pleasure, nor anything amiable, estimable, or respectable, yet experience teaches us, in every country of the world, they attract the attention of mankind more than…learning, virtue, or religion.”

Furthermore, Adams continues, they are sought by the poor, who believe such honors will lift them to equal status with the rich, and they are sought by the rich, who believe that without these symbols they will be lowered to the status of the poor.

This is the great challenge of human progress—we ignore our great potential to focus on silly attempts to impress.

We do it as children, as youth, as adults, and in old age.

The solution, in the case of academia, is to closely avoid putting scholars or administrators in charge of education, but leave oversight to the parents.

For government, the fix is to allow the people to frequently replace their officials at the election booth—to remove them as soon as they forget to do what the people sent them for.

Symbol Above Currency

Adams points out that ribbons, medals, titles, and other symbols of man’s honor, including the white hickory sticks of certain secret societies, aren’t of much use in real life.

Though, if you are freezing, the hickory stick can at least be ignited and bring some warmth.

But these ornaments are nevertheless widely sought because they are symbols of acceptance, fitting in, and impressing others.

Such symbols show that, in fact, the Status Motive is even stronger in humanity than the Profit Motive.

Indeed, giving war heroes and others who accomplish great acts of heroism large sums of money, cars, vacations or estates would be seen as crass by most modern eyes.

Yet these are exactly what many of the ancients gave their champions and heroes, though chariots and carriages were more in vogue than cars.

We give symbols for the highest achievements, precisely because their lack of monetary value communicates just how highly we esteem them—far above money.

For Adams, the honors and symbols are frivolities only because we seek the honors and symbols rather than the actions for which they are awarded.

This is deep insight into human nature, because for true heroes the ribbons and medals mean much less than simply knowing what they did.

Flattery and Failure

It is wonderful to honor heroic acts that truly merit our admiration and thanks, but too often, as Adams puts it, the “great majority trouble themselves little about merit, but apply themselves to seek for honor…”

This is a serious indictment.

He further says that most people try to gain such honors not by going out and serving in ways that merit them.

Such service would be too difficult, or dangerous, or risky.

Besides, just meriting great honors doesn’t ensure that one will receive them.

After all, we are assured, “perception is reality”.

So many people decide that a much better course is to ensure the world’s admiration the old-fashioned way, by directly seeking prestige and hiring publicists, PR firms, and commissioning scholarly studies and the support of experts.

Adams says it this way:

“…by displaying their taste and address, their wealth and magnificence, their ancient parchments, pictures, and statues, and the virtues of their ancestors; and if these fail, as they seldom have done, they have recourse to artifice, dissimulation, hypocrisy, flattery, empiricism…”

But this is more than an interesting philosophical discussion about human nature.

It actually cuts to the very heart of reality.

Because of our thirst for honors, and because façade honors are easier to obtain, all our manmade institutions eventually fail.

Adams mourns that government cannot solve the problems of humanity, nor will institutions of commerce and business.

Plague of Power

Families and churches come the closest, but even here we spend the generations warring about whether husband or wife should be the head, how long fathers should maintain dominance over their sons, and whether newly married couples now report to paternal or maternal grandfathers.

Likewise, too many churches in history took up arms against unbelievers, and various religions and secular groups resort to violence when they fail to convince in other ways.

Indeed, as soon as men create institutions of any kind, they usually begin to war—within the institution and/or with other institutions.

The solutions, the real fixes to our challenges, Adams teaches, will not come from manmade institutions.

We should set up the best institutions possible, but we can’t rely on them for everything because man’s hunger for approval and applause is always at work undermining progress.

Adams quotes the English poets to make his point:

“The love of praise, howe’er conceal’d by art,

Reigns, more or less, and glows, in every human heart;”

—Edward Young

“All our power is sick.”

—William Shakespeare

If “All our power is sick”, indeed. If so, how can mankind progress?

It turns out there is a solution, and Adams is excited to share it.

Building Greatness

In the cases of family, church, relationships and business, one should simply dedicate one’s life and efforts to truly serving in genuine, if challenging, ways that really make a positive difference.

This was also recommended by C.S. Lewis, who said to ignore trying to impress and instead set out to genuinely serve.

Both Adams and Lewis note that such service is only authentic when we give up concern about getting the credit.

But Adams wants our political leaders to do the same.

He sees real government leadership as deep, committed service, devoid of seeking credit or reward.

He doubts that many will truly forget their drive to impress and seek only to frankly serve, but he holds out hope that a few will rise to such heights of true leadership.

The best honors for such exceptionally great leaders aren’t the praise or baubles of men but the highest of all tributes—emulation.

And in this Adams gives us mankind’s solution to its biggest challenges.

Specifically, while mankind limits itself from great achievements to fight the petty battles of impressing others, becoming more impressive than others, fitting in, and fitting in better than others, the solution is to emulate those who do it better.

What Leadership Is

Parents who emulate great parents are the hope of the world, as are great teachers, inventors, artists, statesmen, leaders, entrepreneurs and others who emulate the greats.

Emulation includes improving upon the best of the past, and as generations of parents and other leaders emulate the best and improve upon it, the world drastically improves.

This, as Adams puts it, is a desire not to impress and fit in, “but to excel,” and “it is so natural a movement of the human heart that, wherever men are to be found … we see its effects.”

Moreover, Adams assures us, it blesses communities and society as much as it helps individuals succeed.

For those who are religious, nothing is more effective than trying to emulate the Son of God, the great prophets, Buddha, and other examples of charity, service and wisdom.

We fall short in many ways, but in trying to answer the question, “What Would Jesus Do?,” as the modern saying goes, we reach for our very best.

Our greatest heroes, regardless of our views on religion, should be the great men and women of history whose sacrifice and greatness makes them most worthy of emulation.

Emulation is as strong an emotion as seeking admiration, and in fact most children learn emulation first.

Which brings us to the topic of this article—How to fix Washington and put America back on track as a standard for freedom, opportunity and goodness in the world.

According to John Adams (and C.S. Lewis, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and many others), the answer is not to turn to leadership from our big institutions, even if they have as much power as the White House, Congress, Wall Street, Hollywood, Silicon Valley, the Justice Department, the Federal Reserve or even the Supreme Court and Madison Avenue.

The solution lies in leadership, but not from the top down.

We will not get back on track as a society until we lead from below, until we become a society of leaders, and the right kind of emulation is our most powerful means of lasting influence and change.

Who you and I choose to emulate—really, truly, deeply, fully—will determine the future.

Becoming Our Future

It is the most powerful symbol, because who we want to be like on the greatest days of our lives will color the rest of our time on earth.

But it is much more than a symbol.

Too much of modern life is merely a façade.

Too many of our institutions are hollow shells of what we need them to be—and of what they claim to be.

Too often we choose the path of prestige over the path of quality.

Too frequently we listen to the credible rather than the wise.

Too many of our hours and days are spent on the things that are least important.

It was Nietzsche, I think, who said that modernism began when we started substituting the morning paper for our morning prayers.

Allan Bloom called this the closing of the American mind.

Adams told us that such things are hollow, but in the Information Age the voice of understanding is too frequently drowned out by the roar of the crowd.

In all this, however, there is an anchor.

Who we decide to emulate, and how faithfully we do so, will make the future.

And that goes for Washington as well.

Category : Blog &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Education &Generations &Government &History &Independents &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Politics &Service &Statesmanship

LuAnn Ose

5 years ago

If only I were able to emulate you.