America’s Seven-Party System

September 9th, 2010 // 12:23 pm @ Oliver DeMille

High school civics classes for the past century have taught that America had a two-party system.

And up until the end of the Cold War, this was true. Each party had clear, distinct values and goals, and voters had simply to assess the differences and choose which to support.

Such clarity is long gone today, and there is no evidence that this will change any time soon.

As a result, more people now call themselves “Independents” than either “Democrats” or “Republicans.”

We are led today by the contests and relations of seven competing factions, or parties. These major factions are as follows:

Republicans

1. Nixonians

2. Reaganites

3. Populists

Democrats

4. Leftists

5. Leaders

6. Special Interests

Either/Neither

7. Independents

Neither party knows what to do about this. Both are plagued by deep divisions. When a party wins the White House, these divisions are largely ignored.

During a Party’s time in the White House, the underpinnings of the party weaken as differences are downplayed and disaffection quietly grows.

Fewer people wanted to be identified as Republicans with each passing year under the Bush administration, just as the Democratic coalition weakened during the Clinton years.

This is a trend with no recent exceptions. Being the party in power actually tends to weaken popular support over time.

Governance v. Politics

The emerging and improving technologies of the 1990s and 2000s have reinvented government by forcing leaders to constantly serve two masters: governance and politics.

Governance is a process of details and nuance, but politics is more about symbols than substance.

As I stated in The Coming Aristocracy, before the past two decades politics were the domain of elections, which had a compact and intense timeline.

After elections, officials had a period to focus on governing, and then a short time before the subsequent elections they would return to politics during the campaign period.

Now, however, governors, legislators and presidential administrations are required to fight daily, year-round, on both these fronts.

Both major parties struggle in this new structure. Those in power must dedicate precious time and resources to politics instead of leadership.

Worst of all, decisions that used to be determined at least some of the time by actual governance policy are now heavily influenced by political considerations, almost without exception.

Power facilitates governance, but reduces political strength. Every governance policy tends to upset at least a few supporters, who now look elsewhere for “better” leadership.

While Republicans and Democrats accomplish it in slightly different ways, both alienate supporters as they use their power once elected.

The Loyal Opposition

The party out of power has less of a challenge, but even it is expected to present alternate governance plans of nearly everything — plans which have no chance of ever being adopted and are therefore a monumental misuse of official time and energy — instead of focusing on their vital role of loyal opposition which should ensure weighty and quality consideration of national priorities.

The temptation to politicize this process is nearly overwhelming — meaning that the opposition party has basically abandoned any aspiration or intent to participate in the process of governing and become all-politics, all-the-time.

As a result, American leadership from both parties is weakened.

With the advancement of technology in recent years has come the increased facility for individuals to not only access news and information in real time, but to participate in the dialogue by generating commentary, drawing others’ attention to under-reported issues and ideas and influence policy through blogging, online discussions and grassroots campaigns.

An immensely important consequence of this technological progress has been the fractionalizing of the parties.

Republicans: The Party of Nixon vs. The Party of Reagan

Both Nixon and Reagan were Republicans, but symbolically they are nearly polar opposites to all but the most staunch Republican loyalists.

Reaganites value strong national security and schools, fiscal responsibility, and laws which incentivize small businesses and entrepreneurial enterprises.

Nixonians value party loyalty over ideology, government policy that benefits big business and large corporations, international interventionism and winning elections.

A third faction in the Republican community are the populists.

Feeling disenfranchised by the loss of the Party to the Nixonians, the populists want Americans to “wake up,” realize that “everything is going socialist,” and “take back our nation.”

Identified with and defined by talk-show figureheads with shrill voices, the populists are seen as more against than for anything. They believe that government is simply too big, and that anything which shrinks or stalls government is patently good.

A Bad Day To Be A Populist

The populists are doomed to perpetual disappointment, since any time they win an election they watch their candidate “sell out.”

It is hard to imagine a more thankless job than that of the candidate elected by populist vote; once she takes office she is consigned to offend and alienate either her constituents or her colleagues — most likely both.

She is either completely ineffective at achieving the goals of her constituency, or, if she learns to function within the machine, she has no constituency left.

Any candidate who tries to work within the system will lose her appeal to the populists.

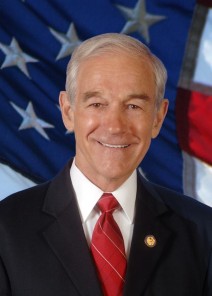

If such a candidate stays focused on principle, like the iconic Ron Paul, many populists will admire his purity but will criticize his lack of substantive impact — his accomplishments are seen as almost exclusively symbolic.

If such a candidate stays focused on principle, like the iconic Ron Paul, many populists will admire his purity but will criticize his lack of substantive impact — his accomplishments are seen as almost exclusively symbolic.

Some of the most influential populist pundits (like Rush Limbaugh) have lost “believers” by being outspokenly populist when it supports the party agenda (like during the Clinton Administration and later in rejecting McCain’s presidential candidacy as too moderate/liberal) and then switching to support the Party (backing President Bush even in liberal policies and supporting McCain when he became the Republican nominee).

This is seen by detractors as manipulative, corrupt and Nixonian at worst, and self-serving, hypocritical and opportunist at best.

Vast Right Wing Conspiracy

Populism is considered “crazy” by most intellectuals in the media and elsewhere.

This is probably inevitable and unchangeable given that the same things which appeal popularly (such as alarmism, extremism, labeling, using symbols, images, hyperbole and appeals to sentimentalism) are considered anti-truth to intellectuals.

Indeed, part of training the intellect in the Western tradition is to reject the message of such deliveries without serious consideration, and dismiss the messenger as either unfit or unworthy to have a serious debate on issues.

Wise intellectuals look past the delivery and consider the actual message. This being said, even when weighed on its own merit the populist message is unpopular with intellectuals.

Populism is based on the assumption that the gut feelings of the masses (The Wisdom of the Crowds) are a better source of wisdom than the considered charts, graphs and analysis by teams of experts.

This hits very close to home for those who make their living in academia, the media or government. So our system seems naturally to pit the will of the people against the wisdom of the few.

Crazy Like a Fox

It is interesting to compare and contrast this modern debate between the wisdom of the populists and that of experts and officials with the American founding view.

The brilliance of the founders was their tendency to correctly characterize the tendencies of a group in society and employ that nature to its best use in the grand design in order to perpetuate freedom and prosperity.

In fact, the American framers did empower the masses to make certain vital decisions through elections. Madison rightly called every election a peaceful revolution.

And, the founders did empower small groups of experts: the framers had senators, judges, ambassadors, the president and his ministers appointed by teams of experts.

Only the House of Representatives and various state and local officials were elected by the masses, and the House alone was given power over the money and how it was spent.

In short: The founders thought that the masses would best determine two things:

1. Who should make the nation’s money decisions, and

2. Who should appoint our other leaders.

Riddle: When Is A Democracy Not A Democracy?

The founders believed that most of the nation’s governance should come from teams of experts, as long as the masses got to decide who would appoint those experts and how much money they could spend.

Such a system naturally empowers and employs both populism and expertise.

If It’s Not Broken, Don’t Fix It

Compare today’s model: Senators are now elected by the populace and the electoral college has been weakened so that the popular vote has much more impact on electing a president than it once did (and than the founders intended), thus increasing the power of the popular vote.

Yet many of the same intellectuals who support ending the electoral college altogether ironically consider populists “crazy” and “extremist.” The incongruity is so extreme that is no wonder many conclude that there must be some dark, conspiratorial agenda driving this trend.

Talking Heads

The reason for this seeming paradox is simple: Where the founding era actually believed in the wisdom of the populace to elect, modern intellectuals seem to believe that few of these “crazies” actually believe what they say they believe.

Many intellectuals think that populists, conservatives and most of the masses are simply following the views provided by talking heads.

For them, populist “wing nuts” have been duped by the sophistries of Rush Limbaugh, Bill O’Reilly, Glenn Beck, Sean Hannity, Ann Coulter, or some other “self-serving anti-intellectual.”

But at its core, the alarmist and wild antics of populist pundits are not the real reason many intellectuals question the sanity of conservative populists.

The deeper reason is that few intellectuals believe that sane people don’t want more government.

They understand Nixonian Republicans and their desire for more power, government support of Big Business and less regulation of corporations. They may not agree with these goals, but they understand them.

They also understand poor and middle class citizens wanting more government help.

And they even understand the Reaganesque vision of fiscal responsibility along with strong schools, security and increased incentives for small business.

Does No Mean Yes?

What intellectuals struggle to understand is lower and middle class voters who don’t want government programs.

For example, few of the populist “crazies” who oppose President Obama’s health care would be taxed to pay for it, and most would see their family’s health care benefits increased by Democratic plans.

So why would they — how could they — oppose it?

Rich right-wing leaders who would bear the costs for health care must have convinced them.

This is a logical conclusion. Rich people opposing higher taxes makes sense. Lower and middle class people supporting increased government aide makes sense.

Rich talk show hosts telling people Obama’s plan is bad makes sense. The people being duped by this makes sense.

What doesn’t make sense, what few intellectuals are willing to accept, is that large numbers of non-intellectuals are looking past alarmist talk show host antics, closely studying the issues and deciding to choose the principles of limited government over direct, personal, monetary benefit.

Intellectuals could respect such a choice; lots of citizens refusing government benefits to help the nation’s economy and freedom would be an amazing, selfless act of patriotism.

But they don’t believe this is happening.

Instead, they are concerned that the “wing nuts” are following extremist pundits and unknowingly refusing personal benefit. That’s “crazy”!

This view is reinforced by the non-intellectual and often wild-eyed way some populists act and talk about the issues.

In this same vein, intellectuals also naturally support the end of the electoral college because it would naturally give them, especially the media, even more political influence.

The most frustrating thing for intellectuals is this: The possibility that these “crazies” aren’t really crazy at all — that they actually see the biased focus and struggle for power by the intellectual media and don’t want to be duped by it.

Such a segment of society naturally diminishes the potential influence of the media, and is treated by many as a threat.

By the way, many conservative populists claim to be Reaganites. In fairness, they do align with a major Reagan tenet — an anti-incumbent, anti-Washington, anti-insider, anti-government attitude. These were central Candidate Reagan themes.

However, once in office, President Reagan governed with big spending for security, schools and the other Reaganite objectives listed earlier.

This is a typical Republican pattern. For example, compare the second Bush Administration’s election attacks on Clinton’s spending with the reality of Bush’s huge budget increases — far above Clintonian levels.

Democrats: Leftists, Leaders and Special Interests

Having covered the Republican Party, the discussion of the Democratic Party will be more simple.

The three major factions are similar: those seeking power, those wanting to promote liberal ideas, and the extreme fringe. Let’s start with the fringe.

Where Republican “fringies” call for the reduction of government, Democratic extremists want government to fund, fix, regulate and get deeply involved in certain special interests.

And while conservative populists are generally united in wanting government to be reduced across the board, Democratic special interests are many and in constant competition with each other for precious government funds and attention.

While Republican extremists see the government, Democrats and “socialists” as the enemy, Democratic radicals see corporations, big business, Republicans and the House of Representatives (regardless of who is in power) as enemies.

Republican “crazies” distrust a Democratic White House, the FBI, Hollywood, the Federal Reserve, Europe, the media and the Supreme Court.

Democratic “crazies” hate Republican presidents, the CIA, Wall Street, Rush Limbaugh, hick towns, gun manufacturers, Fox News and evangelical activists.

Republican extremists like talk show hosts and Democratic extremists like trial lawyers.

How’s that for stereotyping?

A Rainbow Fringe

The Republican populist group is one faction — the anti-government faction. Radical Democrats are a conglomerate of many groups — from “-isms” like feminism and environmentalism to ethnic empowerment groups and dozens of other special interests, large and small, seeking the increased support and advocacy of government.

One thing Democrat extremists generally agree on is that the rich and especially the super-rich must be convinced to solve most of the world’s problems.

Ralph Nader, for example, argues that this must be done using the power of the super-rich to do what government hasn’t been able to accomplish: drastically reduce the power of big corporations.

Because Democrats are currently in power, the extreme factions have a lot less influence within the party than they did during the Bush years — or than Republican extremists do under Obama.

The call for a “big tent” is a temporary utilitarian tactic to gain power when a party is in the minority. When a party is in power, its two big factions run the show.

Call the two largest factions the “Governance” faction and the “Politicize” faction.

For Democrats, the Politicize faction is interested in maintaining national security while trying to reroute resources from defense to other priorities; increasing the popularity of the U.S. in the eyes of the world and especially Europe; promoting a general sense of increasing social justice, racial and gender equality, improved environmental and energy policy; and improving the economy.

A major weakness of this faction is its tendency toward elitism and self-righteous arrogance.

Is That Asking Too Much?

The Governance faction has to do something nobody else — the other Democrat factions, the Republican factions, the Independents — is required to accomplish. It has to bring to pass the following:

- Keep America safe from foreign and terrorist attacks

- Pass a health care bill that convinces Independents of real reform within the bounds of fiscal responsibility

- Bring the unemployment rate down — preferably below 7% within the next year

- Keep the economy from tanking

Capturing The Middle Ground

If the Democratic Governance faction accomplishes these four, it will achieve both its short-term governance and its political goals. If it fails in any of them, it will lose much of its Independent support.

The Obama Administration will maintain its base of Democrat support basically no matter what. And the Republican base will remain in opposition regardless.

But without the support of Independents, the White House will see reduced influence in Congress and the 2010 elections.

And when Democrats create scandals like Clinton’s handling of his affairs or the Obama Administration’s “war on Fox News,” Independents see them as Nixonian, responding by distancing themselves both philosophically and in the voting booth.

Independents are powerfully swayed by “The Leadership Thing,” and Obama clearly has it (as did both Reagan and Clinton — but not Bush, Dole, Bush, Gore, Kerry or McCain). It is doubtful that Candidate Obama will lose in 2012.

But “The Leadership Thing” runs in candidates only — not parties.

Obama won because so many independents supported him. Independents are a separate faction that truly belong to neither party.

Indeed, President Obama united most Democrats to support health care reform — partly by taking on Republicans. If a reform bill takes effect, he will likely win the support of Independents by taking on his own party on a few issues and playing back to the middle.

This is power politics.

The 7th Faction: Independents and Independence

Who are these people that vacillate between the parties? Are they wishy-washy, never-satisfied uber-idealist pessimists? Are they the weakest among us?

Why don’t they just pick a party and show some loyalty, some commitment, like Steelers fans or staunch religionists?

Actually, independents are the most consistent voters in America. True, they fluctuate between parties and seldom cast a straight party ballot, but they vote for the same things in nearly all elections.

In contrast, party loyalists stick with their party even when it adopts policies they patently disagree with. Some might argue that this is a more “wishy-washy” way to approach citizenship and voting.

Independents watch the issues, candidates and government officials very closely, since they don’t rely on party platforms to define their values or on affiliations to bestow their trust.

What They Want

Independents want strong national security, open and effective diplomacy, good schools, policies that benefit small businesses and families, social/racial/gender equality, and just and efficient law enforcement.

They see a positive role for government in all these, and dislike the right-wing claim that any government involvement in them is socialistic.

For example: Taxing the middle class to bail out the upper-middle class (bankers, auto-makers, etc.) is not socialism; it’s aristocracy.

Independents are unconvinced by Republican arguments that government should give special benefits to large corporations, or Democratic desires to involve government in many arenas beyond the basics.

Independents care about the environment, privacy, parental rights, reducing racial and religious bigotry, and improving government policy on immigration and other issues.

A Tough Sell

On two big issues, health care and taxation, Independents side with neither Democrats nor Republicans.

They want good health care laws that favor neither Wall Street corporations (a la Republican plans) nor Washington regulators (e.g. Democratic proposals). They want health care regulations that are truly designed to benefit small businesses and families in order to spur increased prosperity.

Independents want government to be strong and effective in serving society in ways best suited to the state, but they expect it to do so wisely and with consistent fiscal responsibility.

They tend to see Republicans as over-spenders on international interventions that fail to improve America’s security, and Democrats as wasteful on domestic programs that fail to deliver desired outcomes.

They want government to spend money on programs that work and truly improve the nation and the world. They are often seen as moderates because they reject both the right-wing argument against constructive and effective government action and leftist faith in more government programs regardless of results.

They want to cut programs that don’t work, support the ones that do, and adopt additional initiatives that show promise.

American Independents & American Independence

The future of America, and American Independence, will be determined by Independents.

Interestingly, Independents come from all six of the factions mentioned in this article. The one thing they all have in common is that they don’t see themselves as part of a specific party, but rather as independent citizens and voters.

The technologies of the past twenty years have made things more difficult for politicians, but they have made it easier for citizens to stand up for freedom.

What we do with this increase in our potential power remains to be seen.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is the founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

He is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Aristocracy &Featured &Government &Independents &Liberty &Politics &Prosperity