The Jefferson-Madison Debates: The Next Civil War?

May 13th, 2018 // 4:25 pm @ Oliver DeMille

True or False…or False?

It’s getting worse. Just watch the news. This phrase, the “Next Civil War”, was recently used by economic forecaster Harry Dent to describe the growing divide between Red and Blue state cultures. These two sides now disagree with each other to the point that in many cases people experience real hatred for those on “the other side”.

It’s getting worse. Just watch the news. This phrase, the “Next Civil War”, was recently used by economic forecaster Harry Dent to describe the growing divide between Red and Blue state cultures. These two sides now disagree with each other to the point that in many cases people experience real hatred for those on “the other side”.

Former president Barack Obama noted that people who largely get their news from the mainstream media and those who get their news mostly from Fox are basically living “on different planets.” They not only disagree on principles and solutions, he pointed out, but they fundamentally disagree on “facts”. What the Blue culture sees as incontrovertible truths, the Red culture frequently sees as lies. Fake. False. And the opposite is just as true: what the Red culture sees as fact is often considered false by Blue culture.

No wonder the two sides are so angry at each other. When you disagree on what the facts are, the solutions promoted by the other side frequently appear ludicrous. Even dangerous. Both sides, each rooted in its own understanding of reality, watch the other side say and do things that are clearly and painfully hurtful—according to the set of obvious but differing “facts” they each believe.

Roadblocks

This divide is widening. We’ve reached the point that one of the worst things parents can learn about their child’s “significant other” or new fiancé is that he/she is a Republican, or Democrat—depending on the family. Religion, career, ethnicity, education, financial status, and even a criminal history, are largely negotiable in most modern families. But the other political party? Many parents turn Tevye: “If I try and bend this far, I’ll break.”

Lynn Vavreck wrote in The New York Times (January 31, 2017): “In 1958, 33 percent of Democrats wanted their daughters to marry a Democrat, and 25 percent of Republicans wanted their daughters to marry a Republican. But by 2016, 60 percent of Democrats and 63 percent of Republicans felt that way.” And for many, the feelings run very deep. While in 1994 21 percent of Republicans viewed Democrats in the “Very Unfavorable” category, by 2016 the number was 58 percent. (Pew Research Center) In 1994 17 percent of Democrats saw Republicans as “Very Unfavorable”, but the number in 2016 had skyrocketed to 55 percent. (Ibid.)

Aaron Blake summarized this concern in The Washington Post: “If 58 percent of Republicans hate Democrats and 55 percent of Democrats hate Republicans, that would mean about 35 percent of registered voters hate the opposite political party.” (June 19, 2017) “But that’s not quite hate…. 45% of Republicans see the Democratic Party as a threat to the nation’s well-being…. [and] 41% of Democrats see the Republican Party as a threat to the nation’s well-being”. (Ibid.) When you add independents, the “hate” one of the parties (those who see the other party as a threat to the nation) makes up 39 percent of registered voters or “About 1 in 4” Americans. (Ibid.)

There are a lot of others who see the other side in an unfavorable light, around 33 percent of additional Republicans (for a total of 91% with “unfavorable” or “very unfavorable”) and 30 percent of additional Democrats (86% with “unfavorable” or “very unfavorable” views). (Ibid.) Note that all of this occurred before the Trump presidency. Again, this divide is real, and deep. In the Trump era the intensity has only increased.

But does any of this justify the phrase “Next Civil War”? Not yet. Not unless we’re going to surrender to hyperbole. Yet this conflict is escalating in many sectors—it’s moved beyond the traditional battlegrounds of politics and news media to additional culture and power centers including education, television, movies, entertainment awards shows, daily and nightly talk shows (both radio and television), sports, and multiple venues on social media. Even social media and Internet platforms are getting involved by adjusting algorithms to promote certain political leanings—or dampen the voice of those they dislike—often without informing their customers.

Platforms and Soapboxes

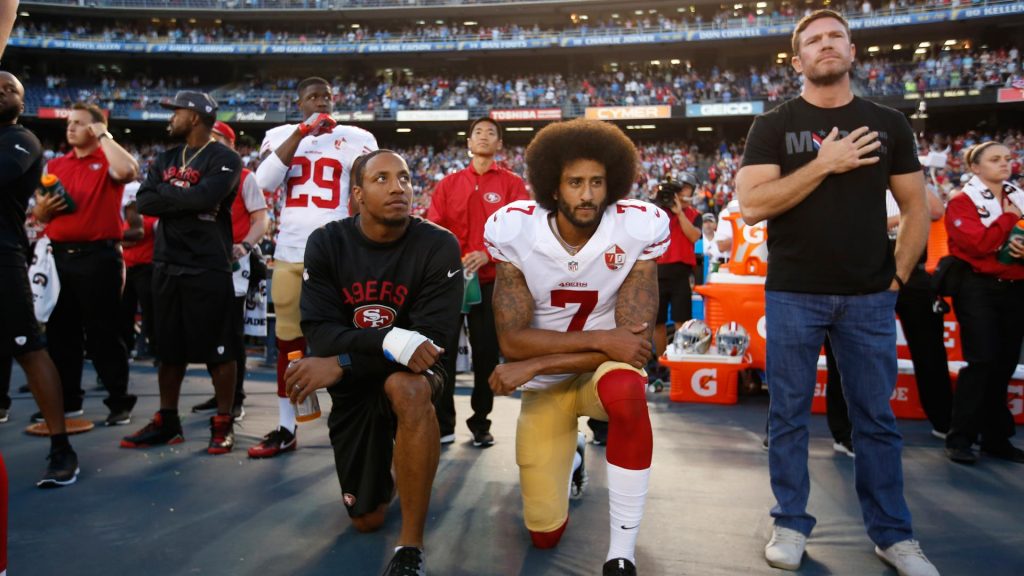

For many Americans, the sight of some NFL players purposely kneeling during the National Anthem is the ultimate symbol of this divide. One side sees young role models and leaders using their public platform to bravely protest government abuse—especially what they consider racially charged police violence. The other side feels hurt and confused by millionaire beneficiaries of the American Dream figuratively spitting on the American Flag and the sacrifice of dead and maimed military heroes.

For many Americans, the sight of some NFL players purposely kneeling during the National Anthem is the ultimate symbol of this divide. One side sees young role models and leaders using their public platform to bravely protest government abuse—especially what they consider racially charged police violence. The other side feels hurt and confused by millionaire beneficiaries of the American Dream figuratively spitting on the American Flag and the sacrifice of dead and maimed military heroes.

It’s difficult to even discuss this situation rationally in many venues due to the raw and heartfelt emotions of people on both sides of the Red-Blue cultural divide.

Sadly, many schools have also become places of great conflict. For example, a national uproar occurred when a middle school teacher assigned her students to write letters to political officials urging them to pass stronger gun control laws. Should teachers tell middle school children what sides to take on political issues? And assign them to engage in activism for one specific side? At what point does teaching become brainwashing? A father of one of the students, a policeman, refused to allow his child to do the assignment. The father deeply disagreed with the politics of the teacher, and many of the other parents disagreed with the politicization of middle school in general. In response to backlash, the teacher allowed students to skip the assignment without penalty, but didn’t suggest writing against stronger gun control if this more accurately aligned with the student’s views. The same week, an elementary student was expelled from school for drawing himself hunting during a “free art” assignment, and a high school teacher was fired for a lengthy history-class soliloquy describing current members of the military as “the lowest of the low” in our society. Red and Blue cultures passionately disagreed on how these events should be handled. Both sides largely see the other’s view as ridiculous and extreme.

Another moment that epitomizes this division occurred on Broadway when the cast of Hamilton stopped the musical midstream to lecture the new Vice President elect, Mike Pence. Hamilton itself is an artistic icon—an American Les Miserables that underscores how the struggles of Washington, Jefferson, Hamilton and their families and peers unleashed freedom in a way that has now spread to people of all backgrounds. The lecture itself was seen by one side as a welcome comeuppance to a dangerous new administration, and by the other as yet another gauche elitist attack against the will of the voters and the American system.

Networks, Numbers, and New Divides

Thankfully this war is largely cultural—it has not devolved into massive physical violence between the two sides of a nation (like the French Revolution, U.S. Civil War, or Russian Revolution, etc.). Hopefully it will always remain peaceful. But in the fight for hearts, there is no doubt that a major civil war for the future of our republic is already under way.

Thankfully this war is largely cultural—it has not devolved into massive physical violence between the two sides of a nation (like the French Revolution, U.S. Civil War, or Russian Revolution, etc.). Hopefully it will always remain peaceful. But in the fight for hearts, there is no doubt that a major civil war for the future of our republic is already under way.

Worse, it is doubtful that any real solution is imminent. When one part of the nation generally believes most of what airs on CNN, ABC, NBC and MSNBC, while another part tends to place more trust in Fox News, Rush Limbaugh, or Trump tweets, the two aren’t going see eye-to-eye on much of anything. And when these two groups are the largest political blocs in our republic, we’re going to have genuine and repeated disagreements.

Perhaps the epicenter of this battle for “the hearts and minds of the people” is found in the media. And this poses a major challenge. Why? Because most of modern media—from both the Left and Right—has three serious problems:

1-It is largely agenda driven (“Forget the facts, full speed ahead!”)

2-It is shallow.

3-It is electronic.

Most people realize the problems with item #1. As a result, they stop listening to media outlets that are clearly against their views—and seem hostile to anyone with a different perspective. This has created another significant problem with modern media:

4-It is isolated. The Right listens to the Right, while the Left listens to the Left. Few listen to both. Few listen to the other side. Over time, media outlets increasingly cater to their narrow audiences, so the extremism increases.

Result: the divisions in our nation are getting wider, deeper, and more susceptible to anger and, too often, extremism and unhealthy thinking and actions.

The Missing Depth

The 2nd and 3rd problems listed just above are equally dangerous. Many people are very busy—work, family, more work, community, more family. Little time is left over for meaningful civic involvement, much less for taking the time to really dig into each day’s news, truly understand what is happening, and go way beyond the 30 second sound bites or even 3 minute segments on any given story. An hour of the news is more than most can spare—and most hour newscasts only provide a very shallow overview of a few of the day’s news topics. In short, shallow. No time for depth.

The 2nd and 3rd problems listed just above are equally dangerous. Many people are very busy—work, family, more work, community, more family. Little time is left over for meaningful civic involvement, much less for taking the time to really dig into each day’s news, truly understand what is happening, and go way beyond the 30 second sound bites or even 3 minute segments on any given story. An hour of the news is more than most can spare—and most hour newscasts only provide a very shallow overview of a few of the day’s news topics. In short, shallow. No time for depth.

The result is that nearly all shows repeat a few top stories, with only a bit of detail. Even if a person watched television all day, he or she would usually only hear about the same top stories, addressed shallowly over and over—with different opinions but nothing really weighty or reflective. Depth is almost unheard of in most of today’s media.

This is especially true of the electronic media. Besides, television, radio, and online media typically interact with human brains more like entertainment than like something really, truly important. When we watch or listen or surf our news, in most cases, we are in the mode of moving quickly from one thought to the next. Even if we try to focus, ads, pop-ups and crawlers invade our screen with multiple headlines and distractions all at once. Our devices were purposely designed this way, in fact.

Reading the news, in contrast, naturally moves the focus into our intellect. A good start. “But nobody wants to read anything longer than a page…” today’s editors assure everyone. Many editors put the limit at “two paragraphs.” If we don’t read more deeply, we’ll truly and literally become a nation of sheep. Deep thinking is needed to deal with the reality of today’s complex and globally-interconnected world—for any citizen. And deep thinking about the news is basically impossible unless we’re reading (or listening/watching to a source that takes) much more than 5 minutes to really address an issue in some depth.

The Jefferson-Madison Debates

The term “fake news” means the following to most people: news that pushes a false agenda, distracts from truth, lies. But “shallow news” is just as bad for the nation. Even “accurate news” that is shallow is a major blow to our society. And this accounts for most of what media consumers experience. When it is both fake and shallow, we’re in real trouble.

The Left and Right argue about which news reports are “fake,” but few even claim to offer real depth in their news. And even fewer consumers seem to be actively searching for and embracing deeper news.

To reiterate: the Red-Blue divisions are growing, and intensifying, and this means that major problems are ahead unless we do something about it. My plan is to write a weekly (or, sometimes, every two week) article that treats real topics in enough depth to help readers take a step back from the constant screaming of electronic news, and really understand a topic (one at a time) enough to see behind the scenes of modern media spin and fake/shallow posturing.

More will, of course, be needed to stop our seeming national sprint toward more civil conflict. But I know this weekly column will make a difference—for those who read it.

More will, of course, be needed to stop our seeming national sprint toward more civil conflict. But I know this weekly column will make a difference—for those who read it.

It was the reading and thinking about articles and pamphlets during the American Founding generation that helped America gain freedom, and deep thinking is vitally needed today. I’m calling this new series of weekly articles The Jefferson-Madison Debates, and I hope you’ll join us.

It’s going to be fun.

— Oliver DeMille

(RSS Feed sign up here ***)

Category : Aristocracy &Arts &Blog &Business &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Education &Entrepreneurship &Generations &Government &History &Independents &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Politics &Producers &Prosperity &Statesmanship &Technology

How to Get the Real News

April 27th, 2017 // 8:39 am @ Oliver DeMille

“Wait!” she said. “Where did you hear that? That’s the opposite of what the news is telling people.”

“Of course it is. I didn’t get this from the news. Or social media.”

Long pause…

“Where did you get it?”

Part I: Conclusion

For many years I’ve recommended that people get their news in a special way: read 2-3 liberal publications, and also 2-3 conservative ones. Pay close attention, and note how both sides spin things. Watch for their assumptions and media agendas. Think about what you read, and draw your own conclusions.

For many years I’ve recommended that people get their news in a special way: read 2-3 liberal publications, and also 2-3 conservative ones. Pay close attention, and note how both sides spin things. Watch for their assumptions and media agendas. Think about what you read, and draw your own conclusions.

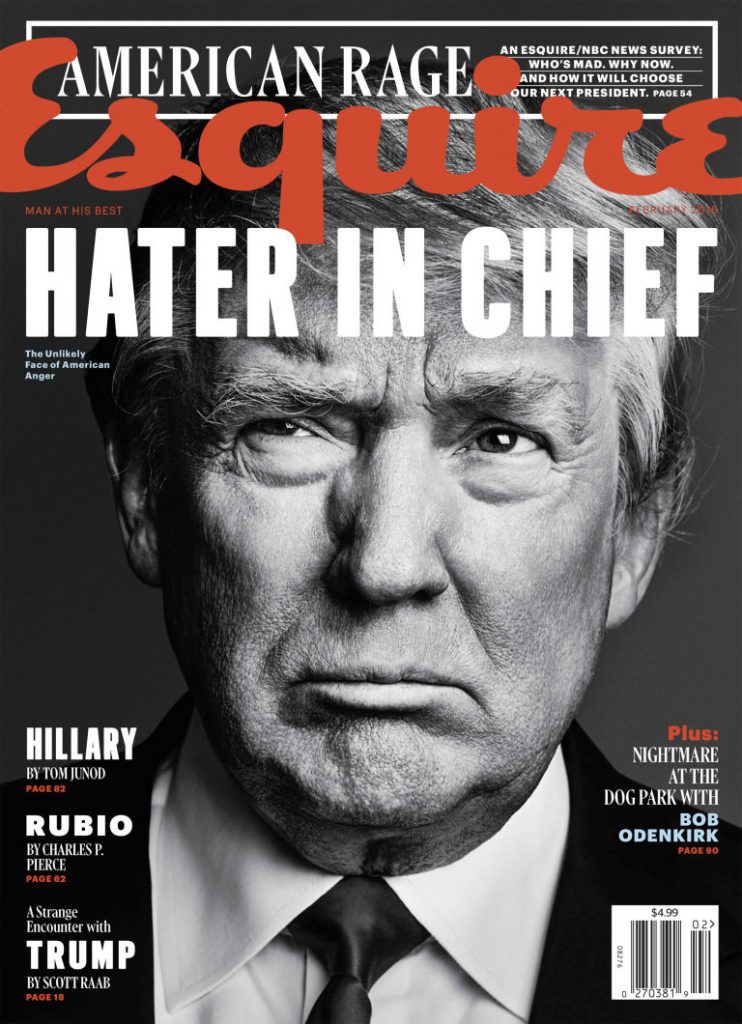

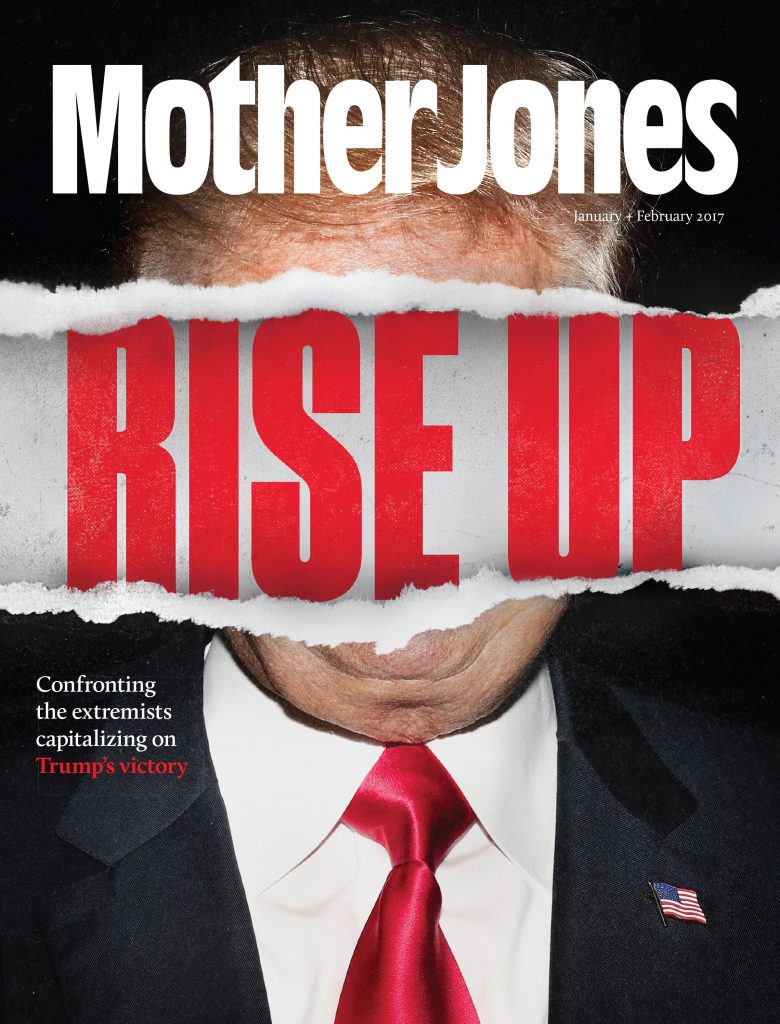

But in the Trump era, it’s no longer this simple. The media has become so biased, so angrily bent on waging war against the current Administration, that even the conservative press frequently joins the mainstream media in its attacks—or in fighting them.

Objectivity in media reports is almost extinct. Manipulative spin is now the one constant in our national–and much of the local–media.

So, where should today’s concerned citizen get the news? The answer to this question is enlightening. In the new era of media—what could arguably be called the post-journalistic era—it’s not just about where you get the news. It’s more about how you read the news. Those who read it the right way will learn what’s really going on. Those who don’t, won’t….

Part II: Example

I open the magazine and read the first article. It’s a liberal magazine, and, like always, I’m enjoying it. Reading what people who disagree with me have to say about the current state of the world is invigorating.

I open the magazine and read the first article. It’s a liberal magazine, and, like always, I’m enjoying it. Reading what people who disagree with me have to say about the current state of the world is invigorating.

When I was younger, it sometimes made me angry. A decade later it made me want to argue. Nowadays, I find myself laughing a lot. Or, once in a while, surprised by a new idea that deserves serious consideration.

For example, the first magazine I read begins with a long editorial about how the economy is “on the rise.” Markets are getting more good news than they have since 2008, and not the “media-spin economic upturn news” that Washington loved during the Obama years, but that always turned out to be false. This time it’s about a real upturn it seems.

Still, the editorial warns, the danger is that people are going to think that things like Brexit and actions of the Trump Administration are responsible for the good economic news. These are all coincidences, apparently, according to the article. Any intelligent person, the magazine seems to be communicating, will clearly realize that there is little or no correlation between Obama/European Union policies and the economic malaise that accompanied them, and the a significant economic upsurge following Brexit/Trump.

My grin turns to laughter. Are they serious? No correlation? Funny. Ironic, but humorous. The same magazine issue has the following question on the front cover: “Is the pope Catholic?” Note that the word “pope” isn’t capitalized. The article takes this question seriously—analyzing the ways the current Pope is rehashing many ideas long considered sacrosanct at the Vatican. This part isn’t funny. Interesting, and important. But I’m pondering, not laughing.

Another article proclaims: “From deprivation to daffodils… All around the world, the economy is picking up.” The cause of this, we are assured once again, has nothing to do with Brexit or conservative policies. In fact, we’re told, these things caused “jitters” and kept the economy from improving sooner.

In the same magazine, we are warned about populist uprisings from the Netherlands, Mexico, and Scotland—all part of a “dangerous” trend. (In fairness, if you favor the elite classes and a system that benefits elites above all others, it actually is a dangerous trend.)

I finish this magazine and pick up the next one. Its purpose, apparently, is to find clever and original ways to criticize Donald Trump and anyone who didn’t happily vote for Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders. A very popular hobby these days.

I finish this magazine and pick up the next one. Its purpose, apparently, is to find clever and original ways to criticize Donald Trump and anyone who didn’t happily vote for Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders. A very popular hobby these days.

But this publication does it in such cerebral language that it’s really fun to read—as if reading it, just soaking it all in, must mean you are one of the smart people, the enlightened, the few, the wise. I do enjoy the creative, engaging writing, even as I find myself disagreeing with much of the content.

I start laughing again. After all, the articles work so hard to sound impartial, journalistic, even erudite. But their frustration and anger with the last election, and the current Administration, shows through on nearly every page.

For example, I read paragraph after paragraph of seemingly objective, unbiased prose (“Just the facts, ma’am, just the facts…”), then I run into words like “vengeful,” “binge,” “vindictive.” The reader is being swayed by largely journalistic writing peppered with emotional triggers. I like it. I mean, it’s interesting, and funny. Besides, the American people are smart enough to see right through this kind of bias, whatever elites think of them. Still, this kind of spin is an art, and the articles I’m reading are skillfully crafted to sway their reader—just like most of the television media.

Pundits on the Right try to do this as well as those on the Left, but the Left has more true artists—masters of this process. Good for them. Seriously. I’m genuinely impressed. Conservatives really do need more effective artists, and more appreciation for well-crafted symbolism.

The End of the Expert

On the less artistic, more direct side of things, one article calls President Trump: “an untruthful, vain, vindictive, alarmingly erratic President.” My first thought is that this is mean-spirited. But wait. I re-read the list of criticisms more carefully. Actually, I tell myself, most of this is fairly accurate, with one exception: What liberals call “untruthful” in Trump is often more a case of inarticulate.

President Trump frequently uses imprecise language, to the point of confusing. It’s a wonderful blessing for his opponents. But I don’t think he knowingly lies as much as the media claims (not in the way career politicians so frequently lie: “If you like your health care provider, you can keep your health care provider” or “insurance premiums will go down,” or “the Benghazi attack was caused by a video made in California,” or “I did not have sex with that woman.”)

But the other things on the list are fair game. Vain. Vindictive. Erratic. The President has exhibited all of these traits at times. I’m laughing again as I ponder this twist—because the real joke is on elites. Seriously: Why did the American people elect someone who is so openly vain and vindictive at times?

This is pretty funny, when you think about it. Liberals want these things to convince Americans that he shouldn’t be president. But those who elected him don’t really care about these things.

In short, liberals seem to want a president they can look up to, hold up as a role model, even canonize (e.g. FDR, Obama). Like medieval courtiers at the palace, they want to put their king on a pedestal. “He’s such a good and great man. She’s such a good and great woman.” They want Josiah Bartlett back in the White House. Or at least Michael Douglass. Or, better still, Kevin Klein’s “Dave”.

Conservatives aren’t thinking of anything so lofty. They don’t need a prophet or a saint in the Oval Office. They just want a president who will reboot the economy and make us safer in the world. Even if he acts like a jerk sometimes.

Liberals don’t seem to get the joke. It’s funny. Think about it: the voters in a majority of states preferred someone who is sometimes vain and vindictive over the elite’s favorite choice—a lifetime politician who checked off all the boxes and did everything the Establishment considers necessary to be in the Oval Office. The voters wanted the exact opposite. The irony is rich.

I finish the second magazine and take a long, deep breath before picking up the next one. But something I just saw keeps nagging me, so I go back to the magazine and look for a certain ad.

Ah…there it is. A promotion for online courses from Julliard. Open to all. “Learn from the Julliard faculty,” the ad proclaims, “classes include…Music Theory 101, Sharpen Your Piano Artistry…. No audition required.” I can hardly believe it. Doesn’t this fly in the face of the elite prime directive: “Rule By Experts—In All Things”? Do we really live in an age where MIT, Harvard and Julliard offer open enrollment classes to everyone? What happened to rule “of the experts, by the experts, and for the experts”? Elites are using technology to promote the appearance of democracy while still focusing on elite rule in every sector.

I open the third periodical in the pile. The lead article picks up right where the other magazine left off: “How Americans Turned Against Experts.” I study this article closely, taking notes in the margins, and then I read a half-dozen others. Apparently, the people just aren’t all that impressed with rule by the experts anymore. (“What have all those experts done for us?” millions are asking. “And why can’t they fix our national problems? What’s taking so long? In fact, why do things keep getting worse in so many ways? If these Ivy-trained experts with all their lofty titles and salaries are so good for America, why don’t they fix things?”)

Cause and Effect?

Finally, I pick up the last magazine in today’s stack. Several of the articles are intriguing. For example, I read: “Poverty has profound effects on the size, shape and functioning of a young child’s brain. Would a cash payment to parents prevent harm from the experience of being poor?” At first blush, it is sad that economic struggles have negative effects on early childhood. It is also not surprising that progressives think passing out money would fix this problem—easily and effectively.

But there’s more to this than initially meets the eye. I’m reminded of the economic idea of “helicoptering”: if the economy is struggling, dump cash from helicopters to poor families. They’ll spend it, and this will provide increased demand, supply, more jobs, and an improved economy. Of course, economists don’t suggest literally throwing cash out of helicopters (like turkeys on WKRP in Cincinnati), but rather depositing money directly into the accounts of people below a certain income level.

Conservatives tend to reflexively balk at such proposals, because they believe in the law of unintended consequences. In other words, paying people without asking them to work for it makes more people want to do nothing, and more citizens become increasingly dependent on government handouts—leaving the productive people to fund it all. Not good for society.

On the flip side, I like to point out to conservative friends that one of the early proponents of such financial “helicoptering” was Milton Friedman. Why? In truth, the direct cost of giving money to poor parents is far less than the amount currently spent by governments to provide all the services they and their children receive.

On the flip side, I like to point out to conservative friends that one of the early proponents of such financial “helicoptering” was Milton Friedman. Why? In truth, the direct cost of giving money to poor parents is far less than the amount currently spent by governments to provide all the services they and their children receive.

If we’re going to offer a lot of socialist programs, let’s at least be efficient.

The real answer is to get rid of socialism altogether. Besides, in the long term, there’s a deeper problem. The idea of giving cash to poor parents in order to help their kids either assumes that the parents will spend it in ways that actually address the problem, or assumes that the government will monitor such spending and force parents to use it “effectively” (an escalation from helicopter parenting to “helicopter government”).

Reading the article even more closely, it becomes clear that there “are dramatic differences from person to person.” Meaning: Some people raised in poverty have normal or even above-average brains, but on average they are smaller, less developed. I’m not laughing anymore. This is deep, and important. The biggest challenge seems to occur where single parents are forced to work so much to pay the bills that there is little time for interaction with young children. The negative consequences last for generations.

Surely our society can find ways to deal with this. Sadly, in our modern world, any talk of real problems seems to turn into demands for more government programs–as if government is the only way to fix anything.

We’re all at fault here: liberals tend to want government to solve everything, and conservatives often fail to provide non-governmental solutions to real challenges that should be addressed by the private sector. Both sides just end up pointing fingers and criticizing, while the problems remain (or grow).

The article provides a lot of interesting details and proposals. I don’t agree with everything I read, but it makes me think outside the box. I finish the magazine and lean back in my chair.

The New News

We have a major problem today with media, but it’s not what most people think. The biggest issue is the fact that few of us are reading enough news. Forget the electronic news. And forget newspapers. Both are too trapped in today’s 24-hour news cycle—and the race for ratings. We need to read bigger ideas, and from a variety of sources.

We have a major problem today with media, but it’s not what most people think. The biggest issue is the fact that few of us are reading enough news. Forget the electronic news. And forget newspapers. Both are too trapped in today’s 24-hour news cycle—and the race for ratings. We need to read bigger ideas, and from a variety of sources.

Readers of quality news magazines and journals are less easily manipulated than those who get their news from TV or social media. Such readers can more adroitly identify spin or media agendas and see right through them—then grin, or laugh, or decide to study more about a certain topic.

If you’re getting most of your news from TV, newspapers, online headlines, or social media—consider moving on. Start reading longer articles, in publications or posts that treat things more deeply, like Foreign Affairs, The Economist, The Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, Vital Speeches of the Day, and issue-oriented online sites and articles.

Read things that make you think, really ponder and analyze. And read a mix of conservative, independent, and mainstream sources.

If you do decide that you prefer to get your news from TV or online news sites, go to the business news. Where the regular news tends to focus on network political agendas, thereby frequently skewing the day’s news stories, the business news will tell you how the economy is actually doing and how today’s events impact it; this is nearly always a more accurate indication of whether to be worried or optimistic about the news of the day. The business news usually tells the story more directly, with less partisan slant.

Whatever your political views, knowing how to get the real news, to see through the media and understand what’s really happening in world events, is part of being an informed and good citizen. All of us benefit from people who do media right.

These two simple changes (1-Reading deeper issue-oriented articles rather than watching or reading the daily event-focused articles, and 2-Going to the business media rather than the political media for a clearer understanding of the news) will drastically increase how well each person understands the news and knows what’s actually happening in the world.

If you stick with the daily TV news or newspaper (or online equivalents), you are always in danger of being another one of those people who actually believe what they hear on the nightly news. In other words…grossly misinformed.

(For further helps on where and how to get the real news, check out my Current Events Course at The Leadership Education Store. This will help you significantly upgrade your ability to see through media spin and know what’s really happening in the world.)

Category : Aristocracy &Arts &Blog &Business &Citizenship &Community &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Featured &Generations &Government &History &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Politics

Symbolic Language

April 22nd, 2014 // 3:32 pm @ Oliver DeMille

Two Different Americas

There are two classes in modern America, the literal class and the metaphorical class. In the increasing divide between the “haves” and the “have nots,” this language difference is central.

In the increasing divide between the “haves” and the “have nots,” this language difference is central.

Those who don’t understand the language of metaphor are falling behind in the widening gap that is the global economy. They are watching their family’s standard of living decrease over the decades.

This trend will only increase in the years ahead.

Those with a quality education learn to think, to readily see symbolism wherever it is found. But most Americans and Westerners are part of the literal class—symbolism is often lost on them.

They tend to see things without the metaphor.

Parental Guidance

For example, last year a long debate raged on social media about whether or not The Hunger Games trilogy was good or bad reading for youth. The most interesting thing about this debate wasn’t the arguments made by either side, but the fact that symbolism was hardly ever part of the debate.

But the symbolism is glaring: A nation sacrifices its helpless children for the convenience, entertainment, and libertine moral values of the urban upper class, while government, media, and big wealth combine to keep their control over the outlying, rural people dedicated to “archaic” family values.

What could be a closer parallel to our modern society? And what metaphor could ever more clearly point out the hypocrisy of the American cosmopolitan class and its views on abortion?

What Was Missed

To anyone trained in symbolism, the metaphor is obvious. We watch children killed for the convenience and political values of the elite class. And note that in The Hunger Games the urban classes have collectivist economic views combined with libertine moral values—the same as those in the real world who support Roe v. Wade and easy abortion laws in modern America.

This is blatant symbolism, but only the upper classes really understood this.

In fact, some of the most vocal voices declaring that The Hunger Games books and movies are inappropriate for youth came from people who are strongly against abortion.

They just didn’t understand that The Hunger Games was probably the biggest, best, and most popular anti-abortion movie ever. This was entirely lost on the literal classes.

When the ruling classes understand literal and symbolic language, while the masses only understand the literal, freedom is in decline and the power of the ruling classes will only increase.

This was true in Shakespeare’s day, in the time of Virgil, and when the Psalms and Proverbs were written.

The elite classes, steeped in the classics and great books that teach readers how to think (especially symbolically), are always going to rule over the literal classes whose education is limited to getting the “right” answers, preparing for jobs and careers, and not really thinking about things symbolically.

Allan Bloom warned that modern America has this problem at the level of Hitler’s Germany.

The Real Fascination

Another example: People in the literal classes can’t quite understand why today’s youth are so intrigued by vampire books, movies, and television programs. “What is this fascination with vampires?” the literal classes ask.

The elite classes, well-versed in metaphor and symbolism, know better. They understand that vampires are symbols of something—something many young people struggle with.

Imagine a society made up of two major groups. First are the hard-working, regular people who live in middle-class neighborhoods, go to work every day, raise families, sleep during the night (because they have to go to their job tomorrow), send their kids to school in order to get a good career in their adult lives, etc.

The second group in society is made up of a few people who have trust funds, inherited wealth, can get in trouble with the law but get out of it relatively easily, stay up through the night at fancy balls and dinners, then go home in the early morning and sleep late into the day, and have more power, wealth, fun and entertaining lives, and sophisticated connections with other aristocrats far beyond the local community—and even around the world.

The first group envies the second, while the aristocratic second group hardly gives a thought to their “inferiors.” Parents of both groups warn their children not to mix with the other group—because it inevitably causes many problems.

This clearly defines two things: 1) an aristocratic society, like all elite societies that have existed in human history, and 2) every group of vampires portrayed in literature, juvenile fiction, and in movies and TV programs.

But the literal classes mostly miss this symbolism. “Why do the kids like vampires?” the literal classes ask.

Some literal writers even try to explain how youth like to be scared, so they love the idea of biting strangers dressed in black. So literal. So shallow.

Answer: The kids don’t love actual vampires, they love the idea of rising into a higher class. In high school, this is a driving passion for many teenagers. If movies are to be believed, it’s the driving theme for most students in most high schools.

In such an environment, vampires are the shortcut to social success. If one bites you (dates you, likes you, includes you in his group, etc.) you immediately climb to a higher social class. The highest social class, in fact.

The one that has the money, the power, the mystery, and the worldwide connections (rather than the homegrown limits of the coal mines, a job at Blue Bell’s Rammer Jammer, or a lifetime of alumni fundraising for the Friday Night Lights).

The fact that many parents tell you to ignore the vampires (“Don’t worry about high school cliques, or being popular. It won’t even matter after you graduate.”) just adds to the intrigue.

Vampires are aristocrats. Elites. People with enough money, power and connections to ignore the limits most people and families struggle with—as youth, and also as adults.

The kids instinctively understand this, though their literal parents may not.

The Old Tool

This language barrier isn’t new.

In aristocratic Britain, the upper classes pronounced words differently than the lower and working classes—so elites would always know who they were dealing with. In fact, the pronunciations were literal (pronounce every syllable) versus symbolic (skip syllables, if you’ve been trained by other aristos and know what to look for).

For example, the word Worchester was pronounced “wor-ches-ter” by the lower classes, but simply “wis-ter” by the nobles. Or the name St. John was pronounced “Saint John” by working classes but “Sinjin” by nobility (see Jane Eyre). There are thousands of similar words.

This boils down to two classes, the Literal versus Symbolic. Checkers versus Chess. “Tell me the right answer, so you can pass the test and someday get a good job,” versus “Tell me your opinion, because there are many possible correct answers, and our purpose is to help you learn how to think—so you can become a leader.”

These are how public schools versus elite prep schools, respectively, generally teach.

The Price of the Literal

Facts versus Metaphor. Precision versus Imagery. One Meaning versus Poetic Allegory.

Again, the elite classes are well educated in both of these dialects. The problem is that the middle and lower classes are not. They only know the literal meanings of words.

This is a growing concern, because it causes increased divisions between the elites and the regular people. The masses don’t understand what is happening to their society, because they don’t speak the language of metaphor. When President Obama promised, “If you want to keep your doctor [under Obamacare], you can keep your doctor,” the two classes heard very different things.

The literal classes heard: “If you want to keep your doctor, you can keep your doctor.” Hearing this, they planned their family and business finances and voted accordingly.

The symbolic classes, trained in metaphor, heard the following: “If you want to keep your doctor, you can keep your doctor, or at least one that is just as good; or, even if you can’t keep your doctor under the new plan, the nation will be better off, so it’s worth the change anyway.”

The symbolic class knows that political promises are rhetoric, meant to win elections—not meant to actually, literally be fulfilled. The literal class is slowly realizing that this is the case, but they still feel lied to by each new candidate. In reality, they just don’t understand metaphorical language.

A teacher I know once shared the following quote by Groucho Marx with her class: “Outside of a dog, a book is a man’s best friend; inside of a dog it’s too dark to read.” One student was very frustrated with this little proverb. When questioned, the student said emotionally, “This is so cruel to dogs. Why would anyone want to read inside of a dog?”

When the literal class doesn’t easily and immediately understand symbolism, it will lose its freedoms to the elite ruling class that does.

The Missed Symbols

I wonder what people will say about the book and movie popularity of Divergent. It is a great symbolic attack on the modern public school system and the way we choose careers and jobs in the U.S., Canada, and Europe—but I bet there will be a number of homeschoolers, charter school and non-traditional educators and parents who miss some key points.

First: this is not a book for youth; the intermittent suggested sensuality that is predictable and “natural” for youth in crisis who depend upon each other without family support is not suitable for most youth.

Second: this book is for adults, and it may be the best promotion for homeschooling and other cutting-edge, new educational choices since…well, ever.

If non-traditional education seizes this opportunity, there will be a lot of support for Divergent, because people will understand its symbolism: Each person is different, and each person has unique genius inside.

The purpose of education is to help each student discover and develop his or her inner genius and passion, and use it to improve and serve the world. When the focus is on making every child fit in, it’s not education at all. At best it’s training, at worst brainwashing.

This is the overarching message of Divergent—but will it be lost on the literal class? I hope not.

We all can benefit from including more symbolic thinking in our reading. It’s like a new mantra for 21st Century leadership: Read more, think more, serve more. And look for symbols and metaphor in everything you read.

Join Oliver for Mentoring in the Classics >>

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Among many other works, he is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, The Coming Aristocracy, and FreedomShift: 3 Choices to Reclaim America’s Destiny.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Aristocracy &Arts &Blog &Book Reviews &Citizenship &Community &Culture &Education &Family &Leadership &Liberty &Mission

The Battle of the 21st Century

June 7th, 2012 // 6:51 pm @ Oliver DeMille

Once, science and religion and art were the same thing—the search for, and attempt to live, truth.

Once, science and religion and art were the same thing—the search for, and attempt to live, truth.

Then came the rise of dominant government and its attempts to control all.

In the Western world, religion and science were seen as the tools of power.

Sides were taken, and conflicts ensued. Left out of the battle, art developed in the shadows.

In the Orient, a different reality evolved.

Art and religion were considered the great centers of power, and so the lines were drawn and battles came.

Science, once at the forefront of Eastern culture, took a back seat. It grew, but behind the scenes.

By the early 21st Century, at least from the perspective of government power, science had become technology and art had become symbol.

Today the globe is increasingly divided between East and West.

A world is growing around China, encompassing the Orient and also much of the Middle East and Africa.

Another world is centered around the United States and includes most of Europe and the two American continents.

Russia and India have yet to take sides, and Japan is caught between its natural philosophical and geographical sides.

These two worlds have been based on the battle between religion and science in the West and the clash between art and religion in the East.

Ironically, the growing conflict between the two worlds coincides with the rise of each culture’s historical shadows—put succinctly, if the battle comes down to technology the East will win and if it comes down to symbolism the West will be victorious.

Tocqueville predicted in the 1830s that the world was destined to be divided by the followers of Russia and the allies of the United States.

He said that if the battle came down to military conflict Russia would win but if it came down to economics the United States would prevail.

Today, we can see the rise of China and the U.S. in similar terms.

But the idea that China will triumph if the battle is technological while the U.S. will succeed in a symbolic challenge seems counter-intuitive. After all, China is struggling to catch up with the U.S. in things technological and China has millennia of experience mastering symbol.

Still, it isn’t old sources of power that win new conflicts. Innovative power takes the day, and the battle of the 21st Century is lining up to be innovative technology versus innovative symbolism.

Ultimately, it all comes down to leadership. Vision. Creativity. Initiative. Ingenuity. Tenacity. Resiliency. Impact. Hope. Inspiration.

China and its associates will likely fight for its global interests using overwhelming centralized state technological might.

America and allies will push for a democratic world utilizing the massive power of the greatest ideas—chief among them freedom.

Both sides will use both technology and symbol, just like both Russia and the U.S. emphasized both military and economic strength.

But ultimately symbol must overcome centralized might.

The future of world freedom and prosperity depend on it.

Hopefully, the history of this century will not unfold this way, but currently the trends are heading in this direction.

The battle has already begun, and China is aggressively pursuing this course while the U.S. stagnating in a rut of decline.

The sooner America gets its act together, the better.

(An excellent book on how to add symbolic thinking to our analytical world is A Whole New Mind by Daniel Pink.)

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Arts &Blog &Culture &Current Events &Featured

Freedom in Decline and the Missing Metaphor

July 6th, 2011 // 9:40 am @ Oliver DeMille

One reason freedom is threatened with serious decline in our time is that metaphor is often missing among those who love liberty.

Our modern educational system has taught most of us to focus on the literal, to separate the fields of knowledge, to learn topics as if they are fundamentally detached from each other, and to build areas of expertise and career around disconnected specialties.

We are even encouraged to separate the various parts of our life—not only math class from English class or gym from history, but also school from family, work from private lives, spouse from child relationships, family from friend relationships, religion from politics, career from entertainment.

Most children and parents leave home in the morning to spend time at school, work and other separate activities—ultimately spending less time with each other than with people outside the family. Anything less than such separation of the various parts of our lives is considered unhealthy by many experts.

Thus it is not surprising that the use of metaphor is often missed in our modern world. We seem to be a nation of literalists now. We understand allegory, comparison, contrast, simile and even imagery, as long as the comparisons are patently apparent or clearly spelled out. Metaphor?—not so much.

There are many exceptions to this, of course, but such literalism is increasingly the norm. Symbol is and will always be important, but the artistic, understated, abstract and poetic is out of vogue in many circles that promote freedom.

Stay Out of Politics

Consider, for example, the way some conservative radio talk-show hosts rant against Hollywood actors or best-selling singers speaking out on political themes. The argument in such cases usually centers on the idea that actors/performers have no business opining on political topics—that, in fact, they know little about such things and should stick to their areas of expertise.

At one level, this assumes that the actors’ roles as citizens are trumped by their careers. Ironically, such talk-show hosts usually give great credence to the voices of regular citizens as part of their daily fare—as long as the citizens tend to agree with the host. Likewise, such hosts frequently seek credibility by bringing like-minded celebrities to their show. Note that this is a favorite tact of media in general—television as well as radio, liberal as well as conservative.

At another level, the idea that actors or other artists are simply entertainers rather than vitally important social commentators misses the deep reality of the historical role of art. Artists are as important to social-political-economic commentary as journalists, scientists, the professorate, clergymen, economists, the political parties or other public policy professionals.

Napoleon is sometimes credited with saying that if he could control the music or story-telling of the nation he would happily let the rest of the media print what it wanted: “A picture is worth a thousand words.” (Or more literally, “a good sketch is better than a long speech.”)

Those who think artists are, or should be, irrelevant to the Great Conversation might consider such artists as Harriet Beecher Stowe, Nietzsche, Goya, Picasso, Goethe, Ayn Rand, C.S. Lewis or George Orwell. Can one really argue that Ronald Reagan, Charleston Heston, Tina Fey, Jon Stewart, Aaron Sorkin or the writers of Law and Order have had only a minor impact on society and government?

Artists should have a say on governance–first because all citizens should have a say, and second because the fundamental role of the artist is not to entertain (this is a secondary goal) but to use art to comment on society and seek to improve it where possible. The problem with celebrity, some would argue, is that many times the public gives more credence to artists than to others who really do understand an issue better. This is a legitimate argument, but it tends to support media types rather than the citizenry.

Early American Art

On an even deeper level, art is not just the arena of artists. Tocqueville found it interesting that in early America there were few celebrity artists– but that most of the citizens personally took part in artistic endeavors and tended to think artistically.

Another way to say this is that they thought metaphorically in the broad sense:

- They clearly saw the connections between fields of knowledge and the application of ideas in one arena to many others

- They understood the interrelations of disparate ideas without having to literally spell things out

- They immediately applied the stories and lessons of history, art and literature to current challenges

Another major characteristic Tocqueville noted in early American culture was its entrepreneurial spirit, initiative, ingenuity and widespread leadership—especially in the colonial North and West, but not nearly so much in the brutal, aristocratic, slave-culture South of the 1830s.

Freedom and entrepreneurialism are natural allies, as are creative, metaphorical thinking and effective initiative and wise risk-taking.

I’ve already written about the great on-going modern battle between innovation and conformity (“The Clash of Two Cultures”), which could be called metaphorical thinking versus rote literalism:

In far too many cases, we kill the human spirit with rules of bureaucratic conformity and then lament the lack of creativity, innovation, initiative and growth. We are angry with companies which take jobs abroad, but refuse to become the kind of employees that would guarantee their stay. We beg our political leaders to fix things, but don’t take initiative to build enough entrepreneurial solutions that are profitable and impactful.

The future belongs to those who buck these trends. These are the innovators, the entrepreneurs, the creators, what Chris Brady has called the Rascals. We need more of them. Of course, not every innovation works and not every entrepreneur succeeds, but without more of them our society will surely decline. Listening to some politicians in Washington, from both parties, it would appear we are on the verge of a new era of conformity: “Better regulations will fix everything,” they affirm.

The opposite is true. Unless we create and embrace a new era of innovation, we will watch American power decline along with numbers of people employed and the prosperity of our middle and lower classes. So next time your son, daughter, employee or colleague comes to you with an exciting idea or innovation, bite your tongue before you snap them back to conformity.

Innovation vs. Conformity

Metaphor gets to the root of this war between innovation and conformity. The habit of thinking in creative, new and imaginative ways is central to being inventive, resourceful and innovative.

Note that all of these words are synonyms of “productive” and ultimately of “progressive.” If we want progress, we must have innovation, and innovation requires imagination. Few things spark creativity, imagination or inspiration like metaphor.

If we want to see a significant increase in freedom in the long term, we’ll first need to witness a resurrection of metaphorical thinking. This is one reason the great classics are vital to the education of free people. The classics were mostly written by authors who read widely and thought deeply about many topics, and even more importantly most readers of classics study beyond narrow academic divisions of knowledge and apply ideas across the board.

In contrast, modern movie and television watchers, fantasy novel or technical manual readers, and internet surfers don’t tend to routinely correlate the messages of entertainment into their daily careers. There are certainly deep, profound, classic-worthy ideas in our contemporary movies, novels, and online. But only a few of the customers watch, read or surf in the classic way—consistently seeking lessons and wisdom to be applied to serious personal and world challenges.

Only a few moderns end each day’s activities with correspondence and debate about the movies, books and websites they’ve experienced with other deep-thinking readers who have “studied” the same sources. Facebook can be used in this way, but it seldom is.

Alvin Toffler called this the “Information Age” rather than the Wisdom Age for this reason—we have so much information at our fingertips, but too little wise discussion of applicable ideas. As Allan Bloom put it in The Closing of the American Mind, people don’t think together as much they used to. Even formal students in most classes engage less in open dialogue and debate than in passive note-taking and solitary memorizing.

Leadership Thinking

All of this is connected with the decline of metaphorical thinking. The point of education in the old Oxford model of learning (read great classics, discuss the great works with tutors who have read them many times and also with other students who are new to the books, show your proficiency in creative thinking in front of oral boards of questioners) was to teach deep, broad, effective metaphorical thinking.

All of this is connected with the decline of metaphorical thinking. The point of education in the old Oxford model of learning (read great classics, discuss the great works with tutors who have read them many times and also with other students who are new to the books, show your proficiency in creative thinking in front of oral boards of questioners) was to teach deep, broad, effective metaphorical thinking.

Such skills could accurately be called leadership thinking, and generations of Americans followed the same model (until the late 1930s) of reading and deeply discussing the greatest works of mankind in all fields of knowledge. Note that thinking in metaphor naturally includes literal thinking– but not vice versa.

This style of learning centered on the student’s ability to see through the literal and understand all the potential hidden, deeper, abstract, correlated and metaphorical meanings in things. Such education trained people to think through—and see through—the promises, policies and proposals of their elected officials, expert economists, and other specialists, and to make the final decisions as a wise electorate not prone to fads, media spin or partisan propaganda.

A New Monument

As a society understands metaphor, it understands politics. This is a truism worth chiseling into marble. When the upper class understands metaphor while the masses require literality, freedom declines.

The surest way to understand metaphor is to read literature and history and think about it deeply, especially about how it applies to modern realities (which is why classrooms were once dedicated to discussion about important books, as mentioned above).

This is why the university phrase “I majored in literature, science, or history” is a middle-class expression while the upper class prefers to say, “I read literature, science, or history at X University.”

The differences here are striking: the upper class never believes it has actually “majored” a topic, while the middle class can seldom claim to have seriously “read” all the great works in any important academic field.

This fundamental difference in education remains a cause of the widening gap between upper and middle class. Indeed, education is a major determining factor of the contemporary (and historical) class divide. It is the ability to think metaphorically (to in fact consider everything both literally and metaphorically) and to automatically seek out and consider the various potential meanings of all things, that most separates the culture of the “haves” from the global “have-nots.”

The Ideology Barrier

In politics, the far left and far right—including, most notably right now, the environmental movement and the tea parties—significantly limit their own growth by staying too literal.

This comes across to most Americans as ineffectively rigid, intolerant, naïve, and even ideological.

The fact that most environmentalists and tea partiers are genuinely passionate and sincere is not a plus in the eyes of many people as long as such activists are seen to be humorless and even angry.

Such activists may not in fact be humorless and angry, but when they seem to be these things, they diminish their ability to build rapport with anyone that does not already understand their point of view.

Feminism once carried these same negatives, but recently gained more mainstream understanding once feminist thinkers moved past literality and used art and entertainment to gain positive support. The gay-lesbian community made the same transition in the past two decades, and environmentalism is starting to make this shift as well (witness the recent hubbub over Cars III).

Whether you agree or disagree with these political movements is not the point; they gain mainstream support by portraying themselves as relaxed, happy, caring and likeable people, and by sharing their principles by telling a story.

False Starts, or, Failed Expectations

President Bush attempted to effect such a change in the Republican Party with his emphasis on Compassionate Conservatism, but this theme disappeared after 9/11.

President Obama exuded this relaxed optimism through the 2008 campaign and several months into his presidency, becoming a symbol of change and leadership to America’s youth (who hadn’t had a real political hero since Ronald Reagan). The president’s cult-hero status disappeared when the Obama Administration’s literality (not liberality) was eventually interpreted as robotic, smug and even defensive.

The White House’s big-spending agenda in 2009-2010, coming on the heels of over seven years of Republican-led overspending, sparked a tea party revolt. It also drove most independents to the right, not because they supported right-wing policies but rather because independents tend to understand metaphor: they saw that the Obama agenda was primarily about bigger government and only secondarily about real change.

To put this as literally as possible, President Obama desired lasting change in Washington, but he cared even more about certain policies which required massive government spending.

There are true supporters of real freedom on all sides of the political table: Democratic, Republican, independent, blue, red, green, tea party, etc. They would all do well to spread deep, quality, creative, artistic and metaphorical thinking in our society.

As Lord Brougham taught:

“Education makes a people easy to lead, but difficult to drive; easy to govern, but impossible to enslave.”

He was speaking not of modern specialized job training but of reading the greatest books of mankind. Leaders are readers, and so are free nations.

Symbolism, Nuance and the Deficits of Literalism

As long as metaphor is missing in our dialogue—not to mention much in our prevailing educational offerings—the people will be continually frustrated by their political leaders.

Campaigns succeed through symbolism, especially metaphor, while daily governance naturally requires a major dose of literalism. Sometimes a significant crisis swings the nation into a period of metaphor, but this mood seldom lasts much longer than the crisis itself.

The most effective leaders (e.g. Washington, Jackson, Lincoln, the Roosevelts and Reagan) are able to communicate a metaphor of American grand purpose even while they govern literally. For example, the Jeffersonian “era” lasted for decades beyond his term of office, building on the American mind captured by the metaphor of freedom; John Adams’ literalism hardly carried him through his one term.

While some of this is the responsibility of the leader, it is ultimately the duty of the people to think in metaphor and understand the big themes and hidden nuances behind government proposals and policies.

In this regard, groups such as environmentalists and tea parties seem to really understand the major trends and are courageously making their voice heard. Unfortunately for their goals, they have yet to effectively present their messages using metaphor. People tend to see them, as mentioned above, as humorless, angry and ideologically rigid.

The irony is rich, because most Americans actually support both a higher level of environmental consciousness and a major increase of government fiscal responsibility. In literal terms, many Americans agree with a large number of green and tea party proposals even as they say they dislike the “environmentalists” and the “tea parties.”

Again, the problem is that these groups tend to emphasize only the literal.

Such examples may be interesting, but the real problem for the future of American freedom is a populace that doesn’t naturally think through everything in a metaphorical way.

A free society only stays as free—and as prosperous—as its electorate allows.

When a nation has been educated to separate its thinking, it tends to be easily swayed by an upper class that understands and uses metaphor—in politics, economics, marketing, media, and numerous walks of life. It becomes subtly enslaved to experts, because, quite simply, it believes what the experts say.

Alternate Timeline of Literalism

If the American founding generation had so believed the experts, it would have stuck with Britain, would never have bothered reading the Federalist Papers, and would have left governance to the upper class.

The capitol would probably be New York City, and the middle class would have remained small. We would be a more aristocratic society, with an entirely different set of laws for the wealthy than the rest.

Such forays into theoretical history are hardly provable, but one thing is clear: American greatness is soundly based on a citizenry that thought independently, creatively, innovatively and metaphorically. The educational system encouraged such thinking, and adult discourse continued it throughout the citizen’s life.

Great education teaches one to listen to the experts, and to then take one’s own counsel on the important decisions.

Indeed, such education prepares the adult to weigh the words of experts and all other sources of knowledge and then to choose wisely.

Sit in chair; open book. Read.

Metaphor matters. Metaphorical thinking is vital to freedom. The classics are the richest vein of metaphorical and literal thinking.

Every nation that has maintained real freedom has been a nation of readers—readers of the great books. Freedom is in decline precisely because reading the great classics is in decline. Fortunately, every regular citizen can easily do something to fix this problem.

The books are on our shelves.

For more on this topic, listen to “The Freedom Crisis.”

Click here for details >>

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Aristocracy &Arts &Blog &Culture &Current Events &Education &Featured &Generations &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Politics