Attention Span: Our National Education Crisis

September 22nd, 2011 // 10:04 am @ Oliver DeMille

This article was originally published as a newsletter article for Oliver’s college students, and was later featured as a chapter in the book A Thomas Jefferson Education Home Companion.

This article was originally published as a newsletter article for Oliver’s college students, and was later featured as a chapter in the book A Thomas Jefferson Education Home Companion.

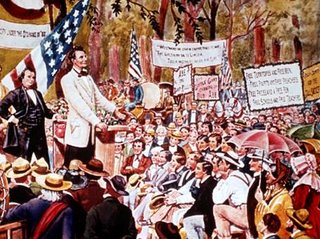

On October 16, 1854, in Peoria, Illinois, Stephen Douglas finished his 3-hour address and sat down. Abraham Lincoln stood.

He “reminded the audience that it was already 5 pm,” and then told them that it would take him at least as long as Mr. Douglas to refute his speech point by point, and that Mr. Douglas would require at least an hour of rebuttal [1].

He recommended that everyone take a one-hour dinner break, and then return for the four additional hours of lecture. The audience amiably agreed, and matters proceeded as Lincoln had outlined.

“What kind of audience was this? Who were these people who could so cheerfully accommodate themselves to seven hours of oratory?”[2]

This was only one of seven debates, and many people attended as many as they could.

In contrast, I was invited as a guest on the early morning NBC station newscast in Yuma, Arizona the day after the Columbine High School tragedy in Littleton, Colorado. The primary purpose of my visit was to deliver lectures at the local community college and then give a speech at an annual foundation banquet—the title of my speech was along the lines of “What Jefferson Would Do to Fix Modern Problems.”

The Columbine coverage took up most of the hour, and when it came time for our interview the anchor turned to me and said, without any preview, something like: “What would Thomas Jefferson think about this Columbine tragedy—you have 30 seconds.”

I don’t remember my exact answer, but I tried to communicate that Thomas Jefferson would not try to analyze and solve such a problem in thirty seconds, and until our means of dealing with serious national problems stops being handled in 30-second sound bite opinions we will continue to see such problems—indeed, they will get worse.

With that our interview was over, we unhooked our microphones and left the studio.

But the event has troubled me ever since. Hundreds of television professionals asked similar questions over the next few days, and have done so repeatedly with hundreds of events since—answers are given in thirty second sound bites, people shake their head at the day’s latest shocking news, and then they go on about their work.

This is how we deal with problems in America today—and then we conclude by calling on government to fix everything. We express opinions–in soundbites on television, at work and social events, and in restaurants and taxis. Then we shake our heads and go back to our lives. We live on a steady diet of opinions, opinions, opinions. In 30-second doses. And then we forget and move on.

What is the difference between these two audiences—those who listened attentively for seven hours to Lincoln and Douglas and came back for more, and those of us who hear and express opinions lightly and then move on?

Not to put too fine a point on it, but these two audiences are drastically different—in their culture, their education, their habits and in their capacity to be free.

The group who heard Lincoln were capable of education, and capable of freedom. The latter group is largely incapable of either unless something changes.

Specifically, a great education ultimately comes down to one thing. Those who have it can gain a superb education. Those who don’t cannot. A nation of people with it can earn its freedom. A nation without it is either not free or in the process of losing its freedom.

If you are going to be a successful leader in the future, you must develop this trait. It is not just a nice thing to have, or a good thing—it is essential; it is vital.

Without it you cannot be a statesman and the world will be led by whoever has it—whether they are virtuous or not, good or evil, dedicated to moving the cause of liberty or some other cause.

You will probably not like to hear what I have to say about it—because it will mean that you have to change, and change is hard; I didn’t like it when I learned it–because I had to change.

Jefferson probably didn’t like it either, but he did it. Lincoln probably didn’t like it; but he did it. You must have this trait if you want to be a successful learner and become a leader. The nation must have leaders with this trait if it is to stay free.

So, if I say things you don’t like, ignore that. Don’t ask, “Do I like what he’s saying?” Ask, “is it true? And what changes will I make because it’s true?”

Each of us needs this trait because each of us wants to fulfill our mission in life, to really make a difference in the world. So, even if it is hard to get this trait–and it is–it is worth it, and it is important.

The vital trait I speak of is attention span.

II. Attention Span and Freedom

Of course, attention span by itself is not enough to guarantee education or freedom, but a person lacking attention span must either develop it or he will not become educated, and a nation without attention span must either gain it or lose its freedoms.

If I were speaking of making money, the point would be obvious. If you don’t go to work and stay a few hours, your paycheck will be small.

In fact, figure out what your paycheck would be if you crammed your work the day before a big bill was due, and you’ll have a pretty good indication of how much that same amount of study is really worth.

Or, figure out how much money you’d make if you spent four years putting in an hour or two a day between fun activities—you certainly wouldn’t make enough to live on.

If you put in that same kind of study, you won’t have much of an education to show for it either. The diploma on the wall may look the same, but it will be empty of meaning.

Without attention span—specific, dedicated time spent at work or managing one’s resources—income and wealth will dry up. The same is true of education, where the currency is study instead of labor, and the commodities are virtue, wisdom and freedom.

But how does a person or nation without attention span develop it, increase it, or improve it? There is only one way: discipline yourself to put in the time.

Speaking of attention span and education: Slow down and learn. Slow down and put in the time reading, writing, discussing, listening, pondering, thinking, praying. Spend hours and hours in the classics, and you will acquire a superb education. A nation of superbly educated individuals will maintain its freedom.

In Lincoln’s day the culture of learning was based around books. Today, as Neil Postman points out in his excellent book Amusing Ourselves to Death, the culture of learning is based on television and internet technology.

All of our forms of public discourse are based less and less on books and more and more on electronic media.

Most of the major decisions of society are made in five places—families, churches, schools, businesses and governments—and four of the five are moving consistently away from books toward electronic media.

Politics is now almost exclusively an electronic event, more and more people attend church in front of their television set, businesses survive through electronic marking, and schools are “computerizing” as quickly as possible—the wave of the future, we are told, is virtual education, virtual politics, e-business and electronic evangelizing.

Even the family is increasingly virtual—parents and children communicate with fax and email, and family time is increasingly spent in front of the television set, except for those off in their own rooms surfing the net.

Now don’t get me wrong: I like the latest hit movie or website as much as anyone, and I believe that television and internet technology are of great benefit to society—they significantly empower business and greatly enhance entertainment.

But they have also displaced books as the source of cultural learning, and this is a very discouraging development because of the impact of society’s morals; but that is not my chief point here.

My point is that it is bad to replace books with television and internet because of the consequences to education and freedom.

Specifically, the medium of the electronic screen teaches at least five deadly fallacies about education, and consequently freedom:

Fallacy Number 1: Learning should be fun.

Indeed, the lesson seems to be that everything should be fun.

The worst criticism of our time is that something is boring, as if that made it less true or less important or less right.

There is nothing wrong with fun, but there is everything wrong with a society whose primary purpose is to seek fun.

In American society, particularly among those under 40, the love of fun is the root of all evil. This is the legacy of the sixties—seeking fun has become a national pastime.

With respect to the education of an adult, fun is simply not a legitimate measurement of value.

Things should be judged by whether or not they are good, true, wholesome, important or right. Commercialistic society judges things by whether they are profitable, and even socialism judges whether something is fair or equitable.

But what kind of a society makes “fun” the major criteria for its actions and choices?

Consider how this lesson impacts the education of youth and adults. Learning occurs when students study. Period. No fancy buildings or curricula or assemblies or higher teacher salaries change this core principle.

Learning occurs when students study, and any educational system is only as good as the student’s attention span and the quality of the materials.

Now, study can be fun, but it is mostly just plain old-fashioned hard work, and nearly all of the fun of studying comes after the work is completed.

In essence, there are really two kinds of fun—the kind we earn (which used to be called “leisure”), and the kind that we just sit through as it happens to us (entertainment). There are very few things in life as fun as real learning, but we must earn it. And this kind of fun always comes after the hard work is completed.

No nation that believes that learning should be fun, in the unearned sense, is likely to do much hard studying, so not much learning will occur.

And without that learning the nation will not remain free. Nor will people stay moral, since righteousness is hard work and just doesn’t seem nearly as fun as some of the alternatives.

No nation focused on unearned fun will pay the price to fight a revolutionary war for their freedoms, or cross the plains and build a new nation, or sacrifice to free the slaves or rescue Europe from Hitler, or put a man on the moon. We got where we are because we did a lot of things that weren’t fun.

Americans today believe that it is their right to have fun. Every day they expect to do something fun, and they expect nearly everything they do to be fun. Most adults eventually figure out that fun isn’t the goal, but many of today’s students firmly believe that learning must be fun; if not, they put down the books and go find something else to do.

Fallacy Number 2: Good teaching is entertaining.

Since fun is the goal, teachers must be entertaining or they aren’t good teachers. “He is boring,” is the worst criticism of a teacher these days.

The problem with this false lesson, besides the fact that some of the best teachers aren’t a bit entertaining, is that it assumes that teachers are responsible for education in the first place.

Now remember, I’m speaking of the role of adult and youth students to own their responsibility for their education.

This is not intended as license for parents and educators to abdicate the responsibility to be all that they can be as mentors.

But think of it: if we, as students, are waiting around for our teachers to get it right or else we’re not gonna study, who really loses?

Whose job is education anyway?

All of us have watched a movie with a bad ending, and since our goal in watching was to be entertained, we are upset that the movie ended that way. We blame it on whoever made the movie; it was their fault.

Our culture approaches teachers the same way—if we weren’t entertained or didn’t learn, it is their fault. “What kind of a teacher is he, anyway; I didn’t learn anything in his class.”

But if I don’t learn something in a class, it is my own fault, no matter how good or bad the teacher is.

Good teaching is a wonderful and extremely important commodity, but that is another essay, and it is not responsible for a student’s success. Students are. To tell them otherwise is to leave them victims who are forever at the mercy of the system.

And history is full of examples of students who owned their role and achieved greatness because they recognized that it was their job to supply the motivation and the effort to gain a great education.

Our society likes to blame its educational shallowness on its teachers because it is just plain easier to blame than to study. And it is easier for parents and politicians to join the blaming game than to set an example of studying that will inspire their youth to action.

The impact on education is clear: We blame teachers and our schools for the problems, while we do everything except the hard work of gaining an education for ourselves, thus inspiring and facilitating our children to do the same.

The impact on freedom is equally direct: Students who have been raised to blame educational failure on someone else usually become adults who expect outside experts to take care of our freedom for us.

Even those who become activists tend to spend a lot of time exposing the actions of others, “waking people up” to what “they” are doing.

And whether “they” refers to conspirators, liberals, or the religious right, the activists seldom do anything about the situation except talk—in more shallow 30-second sound bite opinions.

A corollary of this false lesson is that students need a commercial every 8.2 minutes. We are conditioned to short attention spans, and therefore to shallow educations and nominal freedoms.

The reality is that unless you spend at least two hours on something, chances are you didn’t learn much. Without attention span, little is learned.

Fallacy Number 3: Books, texts and materials should be simple and understandable.

Now, mind you–I’m not suggesting that authors should be purposely obscure or irrelevant. I’m just returning to the idea that we, as students, must step up to whatever obstacles may be in our way.

It’s our job to do whatever it takes to get an education, no matter the quality or interest level of our materials. But even beyond that obvious point, the problem with this error is that the complex stuff is actually the best, the most interesting, ironically the most fun, and certainly the most likely to produce individual thinkers and a free nation.

The classics, the scriptures, Shakespeare, Newton—works really worth tackling are the best and most enjoyable.

Consider the impact of simple materials on education. For example, what kind of nation would the founders have framed had they been taught a diet of easy textbooks, easier workbooks, more quickly understood concepts and curricula?

A free people is a thinking people, and thinking is hard work—it is, in fact, the hardest work, which is why so little of it takes place in a society which avoids pressure and takes the easy path.

The only reason to choose easier curriculum is that it is easier, but the result is weaker graduates, flimsier characters, vaguer convictions and impotent wills.

Thucydides said it bluntly: “The ones who come out on top are the ones who have been trained in the hardest school.”

This is true of individuals and of nations.

I am not saying that everything that is hard has value, but I am saying that most things of value are hard. If your studies weren’t hard, really hard, chances are you didn’t learn much.

Fallacy Number 4: “Balance” means balancing work with entertainment.

Today’s adults don’t usually find out what really hard work is until they graduate and have to support a family. The average person supporting a family in modern America puts in over fifty hours a week at work; in most countries the amount is much higher.

But the American high school system conditions most students to attend class five hours a day and do outside study a few extra hours a week. The rest of the time is filled with activities, friends and occasional family time. And this has become the standard for balance.

Most college students follow suit: they are in class three to five hours a day, they study a couple of hours a day, and they fill the rest of the time with activities and friends.

Again, this is considered “balanced.”

Once people get out of school and go to work, “balance” most often means the need to spend more time with their family.

But while in school, they say it to mean that they need to spend more time with their friends engaging in fun activities. Family time and study time are shoved aside.

One of my mentors, a religious leader from my faith, taught that the right approach to daily life is eight hours a day of sleep, eight hours a day of work, and eight hours a day of leisure.

And he spoke at a time when leisure didn’t mean entertainment.

Indeed, leisure means serving people, studying, learning, being involved in community service and government, and so on—whereas the slaves in Rome were considered incapable of leisure and so their masters gave them entertainment to keep them pacified.

The media age has tried to convince us all, quite successfully, that we need entertainment—and often.

I take the eight hours sleep, eight leisure and eight work quite literally—it is a solid and realistic approach to “balance.”

In all my years of teaching, I have never had a married, working 40 hours a week student complain about not having time to study. They all make the time.

Those who complain are always those wanting more time for entertainment, never those who want more time for work or family.

Every single one of those complaining that they want balance has been someone without a full or steady part time job. That is amazing to me.

The simple truth is that they are right—they do need balance. They need to start working and studying as if they were college students.

Studying a minimum, and I mean minimum, of forty hours a week in college is balance—it balances the pre-college years where most students did real, intensive study only a few hours in their whole life.

And a few college students actually studying enough to become Jeffersons and Washingtons is balance to a whole generation of college students playing around.

If you really want to invoke balance, I think you could make a strong argument that entertainment is not part of a balanced life—unless it is the leisure sort done with family or to learn or serve. Get rid of entertainment time, and fill it with studying, and you will start to find balance.

Until then, you will continue to feel unbalanced—and whatever you blame it on, the study will not unbalance you.

On occasion I have had students who did become unbalanced in the side of their studies, and I have recommended that they cut back and spend more family time. But this has happened perhaps three times out of hundreds of students.

In contrast, it always surprises me who tries to argue for balance—they are usually the ones in no danger whatsoever of becoming unbalanced studiers.

Fallacy Number 5: Opinions matter.

This is perhaps the biggest, most widespread and most fallacious lesson of the electronic age.

A time traveler visiting from history might well consider this the most amazing thing about our age. Everybody has an opinion, which can be delivered in 30 seconds or less, and these opinions are considered newsworthy, valuable, and a sound basis for public policy and individual action.

But an opinion is really just something you aren’t sure about yet–either because you haven’t done your homework, or because after the homework is thoroughly complete the answers are still a bit unclear.

Opinions are at best educated guesses, at worst dangerously uneducated guesses. In any case, opinions are just guesses.

Great people in history know and choose. Opinions are really nothing more than the lazy man’s counterfeit for knowing and choosing. Again, there is a place for opinion, but after the hard work is completed, not as a replacement for it.

In short—opinion is not a firm basis for anything except passing time (which may be one of the reasons the market won’t listen to more than 30 seconds of it at a time).

Imagine what the educational system might look like in a society that values opinions over knowledge. Or try to imagine the future governmental and moral choices of a society where all opinions are created equal, and endowed by their creator with inalienable rights.

Certainly such a society will not be wise, or moral, or free.

III. How to Increase Attention Span

Now, in pointing out these false lessons of the electronic age, my point is not that books are better than computers or televisions. There is nothing I know of that makes paper and binding inherently better than plastic and silicon.

Computers are better than books for many things, such as tracking and storing large amounts of information, speeding up communication and technological progress, and increasing the efficiency and even effectiveness of business.

Television is better than books for many purposes, including mass and speedy communication, business advertising and marketing, and entertainment options where important ideas can be portrayed and carried to the hearts of people more quickly.

My point is not that books are inherently better than electronic screens, nor is it that electronic media is bad. Nor is my point that the electronic media undermines our morals; the truth is that many books are at least as bad.

My point is that books are better than television, or the internet, or computer for educating and maintaining freedom.

Books matter because they state ideas and then attempt to thoroughly prove them.

The ideas in books matter because time is taken to establish truth, and because the reader must take the time to consider each idea and either accept it, or (if he rejects it) to think through sound reasons for doing so.

A nation of people who write and read is a nation with the attention span to earn an education and a free society if they choose.

The very medium of writing and reading encourages and requires an attention span adequate to deal with important questions and draw sound and effective conclusions. The electronic media arguably does not do this in the same way.

Now, idealism aside, the reality is that 30 second sound bites is how public dialogue takes place in our society, and we can either whine about it or we can adapt to the realities and develop our skills to be leaders.

A leader of public dialogue in our day must use the 30 second method; in fact, the reality is closer to 6 seconds than 30.

I am not saying that we should ignore this reality and prepare for 7-hour debates to impact public opinion. The electronic age is real and statesmen should be prepared to utilize it effectively.

But there is a huge difference between those who just polish their media technique and those who do so after (or at minimum, while) acquiring a quality liberal arts education.

Technology is a valuable tool, and a person who has paid the price to know true principles and understand the world from a depth and breadth of knowledge and wisdom, and then applies his or her wisdom through technology is much more likely to achieve statesmanlike impact.

His 6-second sound bites will not be opinions, but rather ideas that have been fully considered, weighed and chosen.

Indeed, and this is my most important point, in the electronic age your attention span is even more important than it was at other times in history.

The future of freedom may well hinge on one thing—our attention spans. And certainly your future success as a leader and statesman depends on your attention span.

One thing is certain: there will be no Lincolns, Washingtons, Churchills, Gandhis, or the mothers and fathers who taught them, without adequate attention span.

CONCLUSION

I wish I had some tricks to give you to increase your attention span. But there is only one that I know of: discipline and hard work, hours and hours and hours studying, with hopefully some prayer and meditation in the mix.

There will be leaders of the next 50 years; I believe you will be among them. But only if you increase attention span.

Otherwise, you will be one of the masses, going along with whatever those in power do to society, led along by your “betters”—not because they are better morally, but because they have a longer attention span.

Too many leaders in history have been people without virtue, who ruled because they had the knowledge. Knowledge truly is power. In this day, it is time for people of virtue to also become people of wisdom.

I challenge each of you to be one of them.

Don’t let your habits of entertainment, your attachment to fun and slave entertainment stop you from becoming who you were meant to be. Become the leader you were born to be—spend the hours in the library. Let nothing get in your way.

Many things will arise to distract you; study will often seem the least attractive alternative for the evening. But you know better. You were born to be the leaders of the future.

Now do it—not in 30-second sound bites of opinion, but in seven to ten hour daily stretches of building yourself into a leader, a statesman, a man or women capable of doing the mission God has for you.

Endnotes:

- Postman, Neil. 1985. Amusing Ourselves to Death. New York: Penguin Books. p.44

- Ibid.

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, 1,1.84.4. For a fuller treatment of this subject, see Josiah Bunting III. 1998. An Education for Our Time. Washington D.C.: Regnery Publishing, Inc.

Category : Blog &Citizenship &Education &Generations &Government &History &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty

A New Definition of Success

August 3rd, 2011 // 10:46 am @ Oliver DeMille

The Religion of Prosperity

The lasting legacy of the twentieth century may be its materialistic definition of success.

Indeed, the “religion” of prosperity has grown to dominate politics, philosophy, religious debate, family and community culture and even education (people sent their children to school with patently career/financial goals).

Even the enemies of prosperity have learned to argue in blatantly materialistic language: Marx believed in a world dominated by conflict between poor and wealthy classes, Hitler argued for economic supremacy of one nation (based on his horrific view of racist supremacy), and Stalin, Mao and a host of dictators amassed power and wealth to themselves and those who served them.

Altruistic movements from various religions and important philosophies (such as feminism, tolerance, environmentalism, etc.) struggled to gain support until they learned to make their case in terms of profitability.

The typical approach to materialism by intellectuals has usually been either to denigrate mankind’s natural materialism and its excesses as “unfettered greed,” or, less frequently, to side with the “virtue of prosperity” perspective.

This debate between the so-called “virtuous poor” and the “virtuous wealthy” made its rounds through politics, academia, media, religion and art.

Science tried to arrive at conclusions based on various studies of socio-economic behavior.

Economists even got into the mix—for example, John Maynard Keynes said that as societies become more and more prosperous, they begin to seek success in things beyond financial increase.

A New Consensus

In the twenty-first century, it appears that a new consensus is emerging—and it’s not what you might think.

In fact, like the earlier materialistic debate (Success 1.0), there are two main perspectives on the new definition of success (Success 2.0).

The first is the “meaning” view, which has become well-known through our modern entertainment.

In this worldview, depression and poverty are bad, financial prosperity is good, and financial prosperity along with a life of real meaning is success.

Steve Jobs popularized this view when he told a graduating class that we should all spend our work lives doing things we really care about and enjoy.

Popular courses at Harvard, Stanford and other prestigious schools on Happiness in Life, or How to Be Happy, have received a great deal of media coverage—and more students than typical science, history or even finance classes.

And why not?

After all, happiness is a concrete feeling that brings its own rewards.

Positive Psychology

A whole new academic field, Positive Psychology, has risen in just the past two decades with a focus on happiness as the real measure of success.

The findings of Positive Psychology are interesting: people typically have more power over their immediate happiness than their immediate wealth or attractiveness, our thoughts have great impact on our happiness, and focusing effectively on happiness brings instant results that are often more pleasant than the noticeable rewards of food, alcohol, sex or even exercise, for example.

Moreover, the growing Success 2.0 movement has adopted some of the assumptions from both sides of the twentieth century debate on materialism: it argues that some material success is needed to maintain long-term happiness and also that at some point enough is enough and people will find more happiness by enjoying family, fun and giving to those in need than by seeking more money.

This view rejects the extremes of both the “unfettered greed” and “virtuous poor” arguments, while adopting the moderate views of both: meaningful work and a liberal flow of money helps one’s happiness, as does working to live (rather than living to work), spending time with family and friends, and giving needed service and monetary donations to help others.

In short, the new definition of success argues that financial prosperity is good and that those who attain it will find more happiness by seeking lives and work with real meaning including service to others.

As a review of Martin Seligman’s book Flourish put it:

“These days, we are hungry for a new definition of the ‘good life.’ Fractured relationships, crumbling economies, environmental crises, and a continuous state of war all have played their part in chipping away at what was once thought to be the basis for happiness…

“Dr. Seligman introduces the ‘New Prosperity,’ a concept based in optimism, and he shows how it affects everything from the health of a marriage, to recovery from illness, to the fluctuations of the stock market. Rather than focusing on gross domestic product, his new vision of prosperity, combines wealth with well-being…” (Spirituality & Health, July-August 2011).

But not everyone is buying the new definition of success.

For example, while men are three times more likely to find a happy woman more attractive than a proud woman, women are five times more likely to find a proud man more attractive than a happy one (Harper’s, August 2011).

And as the Tiger Mom debate shows, a lot of parents are still convinced that success for their children means prosperity through an Ivy League degree and a highly-compensated profession.

The fact that such a life is likely to be less about leadership or deep meaning than “high class drone work” is usually ignored by proponents of old-style success (Sandra Tsing Loh, “My Chinese American Problem—and Ours,” The Atlantic, April 2011).

Likewise, there is a second, darker, side of the Success 2.0 movement.

The Glory Years

Instead of a moderate combination of the following mantras 1) “work hard to build financial success,” and 2) “don’t lose your life in work, but use work as a support to a great life with family, friends and meaningful service,” some are taking the de-emphasis on career success as permission to avoid work and accomplishment altogether.

“Have fun, hang out with friends, party, live with your parents to avoid expenses, and forget about anything that takes hard work,” is gaining popularity.

This view is not lost on marketers who see college as the “glory years” of partying rather than the hard work of study to obtain an excellent education or prepare for one’s career.

For example, I recently purchased notebooks and pens at Wal-Mart’s “Back to School” sale.

A number of shelves were dedicated to supplies parents, kids and teachers will need for school—calculators, binders, pencils, backpacks, filler paper, markers, and more.

On an adjacent display, several large signs announced: “Back to College Sale!”

Interested, I walked over to see what the college sale had to offer different from the elementary/high school displays.

Imagine my surprise when the entire “Back to Colllege” sale, which took up a lot of floor and shelf space, consisted of toothpaste, deodorant, mouthwash and shampoo.

I suppose these are important for college students as much as anyone else, but why was there absolutely nothing related to academics?

I think this is rather poignant.

The tools of college “success,” at least for the Wal-Mart marketers (and I think they have a pretty good sense about the views of their target audience), centered around social acceptability and having fun.

CAKE!

Of course, any university campus probably includes students seeking a fun social life, a quality education, and preparation for a meaningful and rewarding career.

The point is that in the twenty-first century students are more likely to want all three, while last century these three groups were more frequently divided into distinct cliques.

Even where past students combined two of these goals (e.g. a fun social life and career preparation), they tended to clearly prioritize one over the other. Most of today’s students seem to want all three—at the same level of priority.

In short, the old formula of Success = Financial Prosperity is being replaced with a new view that Success = Real Happiness (Financial Prosperity + Meaningful Work + Flourishing Relationships + Significant Service).

With this new math, keeping score may be more complex and more accurate.

Daniel Pink pointed out that the theme of people giving up relationships for their work has been replaced in Hollywood and television productions with people putting relationships above career but finding ways to make them both work.

They want to have their cake and eat it too—or, on the “dark” side, to just enjoy cake.

There is probably little need to worry about those who have decided, for now, to loaf through life.

It almost certainly won’t last.

Success, both the 1.0 and 2.0 varieties, is a kind of widespread de-facto American religion.

As one author wrote of Americans:

“What a curious people. Their mania for self-improvement encompassed everything that touched them, and they resented the cost of every change. They were proudly self-reliant and quick to assign blame to others for their disappointments.

“They were certain theirs was the most enlightened and envied society on earth, that human history was mostly a chronicle of their achievements, and were convinced, too, that their country was constantly in need of repair. Everything they had was better than what any other people had, including their form of government, and nothing was good enough. They believed in themselves…

“For all its power and influence, its abundance and enterprise, [America] was still an immature society: impatient, demanding, not comfortable with introspection, frivolous and audacious” (O, anonymous).

But when it comes time to do the big things, America has repeatedly risen to the occasion.

It has sometimes taken crisis to bring Americans to the table, but once they come they sway everything in their path.

I am convinced that the current generation will do the same.

Churchill quipped that Americans can be counted on to do the right thing after they have exhausted the other possibilities.

Seligman suggests that there are ways to do important things that are not rooted in crisis.

For example, he “presents a rather startling idea, given the current state of affairs: that if history were to repeat itself, such a focus might result in a new Renaissance, appropriate for the twenty-first century but similar to the one that occurred when mid-fifteenth century Florence—rich, well-fed, and at peace—decided to invest its wealth in beauty rather than in conquest” (Spirituality & Health, July/August 2011).

We need to overcome a few challenges before we fully engage the idealism we are capable of.

An estimated 85% of 2011 college graduates are moving back home after graduation (Harper’s, August 2011), an alarming reality for their Boomer generation (born 1946-64) parents.

Likewise, the X generation (born 1965-1985) has reluctantly avoided taking on the responsibilities of past generations.

Up and At It

But when the times require, these generations will grow up and lead out.

Like Shakespeare’s Henry V, generations X and Y (born 1985-2005) grew up being told that world crisis was ahead and that they would have to sacrifice and lead to improve the world.

They subsequently attempted to prolong and enjoy their youth as long as they could.

But like young Henry, when they are called upon by world events, they will be up to the task.

Many members of Gen X and Gen Y worried that 9/11 was such a call, then relaxed as things seemed to normalize.

They worried that the Great Recession was their call, and they are still keeping one eye on this possibility, even while they cling to disappearing hopes for lives of perpetual youth.

Despite their fears, history makes it clear that their time will come, and current trends indicate that they will approach it with a new view of what success means.

In the 1980s and 1990s, a lot of people wanted to “get rich and get out.”

Today, many Americans are restructuring their careers or engaging entrepreneurial and other non-traditional enterprises specifically to combine their hard work with more money, more time with family and hobbies, and more service and charitable contributions.

Success 2.0 is a good change for America, and it broadens the opportunity for everyone in a free society to truly succeed.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Blog &Citizenship &Culture &Economics &Education &Entrepreneurship &Family &Featured &Generations &Leadership

Meritocracy is Elitism

July 19th, 2011 // 6:01 am @ Oliver DeMille

Modernism dislikes all types of elitism– except for meritocracy.

When elite status is merited, according to this view, it is a good thing.

In such a society, our elites are:

“…made up for the most part of bureaucrats, scientists, technicians, trade-union organizers, publicity experts, sociologists, teachers, journalists, and professional politicians. These people, whose origins lay in the salaried middle class and the upper grades of the working class, had been shaped and brought together by the barren world of monopoly industry and centralized government.”

Cool quote, right?

This was written by George Orwell in his description of Big Brother’s society in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Some may think that a meritocracy is the same as Thomas Jefferson’s “natural aristocracy,” but in fact the roots of the two are quite different.

In a meritocracy some rise to elite status through their individual merit, which is determined by the institutions of society.

In short, the current elites get to choose their successors—those of merit determine which people in the rising generation are to be people of “merit.”

In contrast, Jefferson’s natural aristocracy rose because of their “virtue, wisdom and service” to humanity.

And the current societal servants don’t choose tomorrow’s natural servants—they arise naturally according to their service.

Meritocracy offers special perks and benefits for those who are accepted by the current generation of elites.

A natural aristocracy looks around, sees needs and gets to work meeting these needs.

Meritocracy is the best way to choose elites (far better than basing it on land ownership or heredity, for example), but elitist society of any kind is far from the best choice.

Leaders arising naturally through genuine merit is a different thing than meritocracy.

Government by the people is a real concept, not just an idealistic dream.

It gave us the most free and prosperous nation and society in history, and it can do so again.

To repeat: merit, not meritocracy.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Culture &Education &Featured &Leadership &Postmodernism

Where is Wisdom?

July 8th, 2011 // 7:18 am @ Oliver DeMille

Throughout the history of Western Civilization, a high priority has been placed on Wisdom.

The great classics are the Western world’s repository of wisdom, and the application of wisdom to governance, art, science, business and all fields has resulted in success and progress.

Over time these two children of wisdom (progress and success) started their own traditions and today they are competing schools of thought replete with their own unique literature, institutions and promoters. Unfortunately, both have largely lost touch with their original connection to Wisdom.

In politics, the left is dedicated to progress and the right to success. Nearly everything conservative politics supports is based on the goal of achievement and success, while most of the liberal agenda cares primarily for social progress.

In science and the arts this division fuels the split between artists/scientists and mere marketers, and religion has found a role in modernism partly as a voice against excesses of the search for progress and success.

Professions in business, law, medicine, journalism and education have long been places where leaders could promote success and societal progress, but in recent decades the emphasis on wisdom in the professions has waned.

Attorneys, doctors, professors, journalists and executives are very different people when they are earning than when they are learning, as an attorney friend told me.

As a group, the professions have split—some professionals on the conservative, success-oriented side of the ledger with its focus on achievement and others on the liberal, progressive side and its belief in institutional power and government programs.

The fact that in all of this the goal of a wisdom society is almost lost is a modern tragedy. Unless it is reversed, it will only be the first tragedy of many—societies which lose their focus on seeking and applying wisdom inevitably lose their prosperity, freedoms, strength, power and standard of living.

The likelihood of Washington fixing this problem is very slim—Washington is, in fact, the epicenter of the problem.

The party of progress and the party of success constantly block each other’s goals, ignoring wisdom in a battle which has kept the nation in a rut now for decades.

As a society, we seem to want our political leaders loyally partisan rather than notably wise.

If politicians won’t solve our problem, where will wisdom leadership come from in our society? Go to a major bookstore—a few shelves of success literature are surrounded by many shelves promoting societal progress.

The coffee shop, small reading tables, and dress of the shoppers point to progressive society.

The occasional suit enters briskly, finds what he wants, and exits. Too busy to lounge with the other readers, he often skips the store and sends an assistant or gets his books online.

This description is, by the way, a precise depiction of our university campuses.

The thinking style of life and the active style are too seldom combined, and a result is that wisdom is too often lacking. This needs to change, or the future of freedom will suffer.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Blog &Citizenship &Culture &Education &Featured

Freedom in Decline and the Missing Metaphor

July 6th, 2011 // 9:40 am @ Oliver DeMille

One reason freedom is threatened with serious decline in our time is that metaphor is often missing among those who love liberty.

Our modern educational system has taught most of us to focus on the literal, to separate the fields of knowledge, to learn topics as if they are fundamentally detached from each other, and to build areas of expertise and career around disconnected specialties.

We are even encouraged to separate the various parts of our life—not only math class from English class or gym from history, but also school from family, work from private lives, spouse from child relationships, family from friend relationships, religion from politics, career from entertainment.

Most children and parents leave home in the morning to spend time at school, work and other separate activities—ultimately spending less time with each other than with people outside the family. Anything less than such separation of the various parts of our lives is considered unhealthy by many experts.

Thus it is not surprising that the use of metaphor is often missed in our modern world. We seem to be a nation of literalists now. We understand allegory, comparison, contrast, simile and even imagery, as long as the comparisons are patently apparent or clearly spelled out. Metaphor?—not so much.

There are many exceptions to this, of course, but such literalism is increasingly the norm. Symbol is and will always be important, but the artistic, understated, abstract and poetic is out of vogue in many circles that promote freedom.

Stay Out of Politics

Consider, for example, the way some conservative radio talk-show hosts rant against Hollywood actors or best-selling singers speaking out on political themes. The argument in such cases usually centers on the idea that actors/performers have no business opining on political topics—that, in fact, they know little about such things and should stick to their areas of expertise.

At one level, this assumes that the actors’ roles as citizens are trumped by their careers. Ironically, such talk-show hosts usually give great credence to the voices of regular citizens as part of their daily fare—as long as the citizens tend to agree with the host. Likewise, such hosts frequently seek credibility by bringing like-minded celebrities to their show. Note that this is a favorite tact of media in general—television as well as radio, liberal as well as conservative.

At another level, the idea that actors or other artists are simply entertainers rather than vitally important social commentators misses the deep reality of the historical role of art. Artists are as important to social-political-economic commentary as journalists, scientists, the professorate, clergymen, economists, the political parties or other public policy professionals.

Napoleon is sometimes credited with saying that if he could control the music or story-telling of the nation he would happily let the rest of the media print what it wanted: “A picture is worth a thousand words.” (Or more literally, “a good sketch is better than a long speech.”)

Those who think artists are, or should be, irrelevant to the Great Conversation might consider such artists as Harriet Beecher Stowe, Nietzsche, Goya, Picasso, Goethe, Ayn Rand, C.S. Lewis or George Orwell. Can one really argue that Ronald Reagan, Charleston Heston, Tina Fey, Jon Stewart, Aaron Sorkin or the writers of Law and Order have had only a minor impact on society and government?

Artists should have a say on governance–first because all citizens should have a say, and second because the fundamental role of the artist is not to entertain (this is a secondary goal) but to use art to comment on society and seek to improve it where possible. The problem with celebrity, some would argue, is that many times the public gives more credence to artists than to others who really do understand an issue better. This is a legitimate argument, but it tends to support media types rather than the citizenry.

Early American Art

On an even deeper level, art is not just the arena of artists. Tocqueville found it interesting that in early America there were few celebrity artists– but that most of the citizens personally took part in artistic endeavors and tended to think artistically.

Another way to say this is that they thought metaphorically in the broad sense:

- They clearly saw the connections between fields of knowledge and the application of ideas in one arena to many others

- They understood the interrelations of disparate ideas without having to literally spell things out

- They immediately applied the stories and lessons of history, art and literature to current challenges

Another major characteristic Tocqueville noted in early American culture was its entrepreneurial spirit, initiative, ingenuity and widespread leadership—especially in the colonial North and West, but not nearly so much in the brutal, aristocratic, slave-culture South of the 1830s.

Freedom and entrepreneurialism are natural allies, as are creative, metaphorical thinking and effective initiative and wise risk-taking.

I’ve already written about the great on-going modern battle between innovation and conformity (“The Clash of Two Cultures”), which could be called metaphorical thinking versus rote literalism:

In far too many cases, we kill the human spirit with rules of bureaucratic conformity and then lament the lack of creativity, innovation, initiative and growth. We are angry with companies which take jobs abroad, but refuse to become the kind of employees that would guarantee their stay. We beg our political leaders to fix things, but don’t take initiative to build enough entrepreneurial solutions that are profitable and impactful.

The future belongs to those who buck these trends. These are the innovators, the entrepreneurs, the creators, what Chris Brady has called the Rascals. We need more of them. Of course, not every innovation works and not every entrepreneur succeeds, but without more of them our society will surely decline. Listening to some politicians in Washington, from both parties, it would appear we are on the verge of a new era of conformity: “Better regulations will fix everything,” they affirm.

The opposite is true. Unless we create and embrace a new era of innovation, we will watch American power decline along with numbers of people employed and the prosperity of our middle and lower classes. So next time your son, daughter, employee or colleague comes to you with an exciting idea or innovation, bite your tongue before you snap them back to conformity.

Innovation vs. Conformity

Metaphor gets to the root of this war between innovation and conformity. The habit of thinking in creative, new and imaginative ways is central to being inventive, resourceful and innovative.

Note that all of these words are synonyms of “productive” and ultimately of “progressive.” If we want progress, we must have innovation, and innovation requires imagination. Few things spark creativity, imagination or inspiration like metaphor.

If we want to see a significant increase in freedom in the long term, we’ll first need to witness a resurrection of metaphorical thinking. This is one reason the great classics are vital to the education of free people. The classics were mostly written by authors who read widely and thought deeply about many topics, and even more importantly most readers of classics study beyond narrow academic divisions of knowledge and apply ideas across the board.

In contrast, modern movie and television watchers, fantasy novel or technical manual readers, and internet surfers don’t tend to routinely correlate the messages of entertainment into their daily careers. There are certainly deep, profound, classic-worthy ideas in our contemporary movies, novels, and online. But only a few of the customers watch, read or surf in the classic way—consistently seeking lessons and wisdom to be applied to serious personal and world challenges.

Only a few moderns end each day’s activities with correspondence and debate about the movies, books and websites they’ve experienced with other deep-thinking readers who have “studied” the same sources. Facebook can be used in this way, but it seldom is.

Alvin Toffler called this the “Information Age” rather than the Wisdom Age for this reason—we have so much information at our fingertips, but too little wise discussion of applicable ideas. As Allan Bloom put it in The Closing of the American Mind, people don’t think together as much they used to. Even formal students in most classes engage less in open dialogue and debate than in passive note-taking and solitary memorizing.

Leadership Thinking

All of this is connected with the decline of metaphorical thinking. The point of education in the old Oxford model of learning (read great classics, discuss the great works with tutors who have read them many times and also with other students who are new to the books, show your proficiency in creative thinking in front of oral boards of questioners) was to teach deep, broad, effective metaphorical thinking.

All of this is connected with the decline of metaphorical thinking. The point of education in the old Oxford model of learning (read great classics, discuss the great works with tutors who have read them many times and also with other students who are new to the books, show your proficiency in creative thinking in front of oral boards of questioners) was to teach deep, broad, effective metaphorical thinking.

Such skills could accurately be called leadership thinking, and generations of Americans followed the same model (until the late 1930s) of reading and deeply discussing the greatest works of mankind in all fields of knowledge. Note that thinking in metaphor naturally includes literal thinking– but not vice versa.

This style of learning centered on the student’s ability to see through the literal and understand all the potential hidden, deeper, abstract, correlated and metaphorical meanings in things. Such education trained people to think through—and see through—the promises, policies and proposals of their elected officials, expert economists, and other specialists, and to make the final decisions as a wise electorate not prone to fads, media spin or partisan propaganda.

A New Monument

As a society understands metaphor, it understands politics. This is a truism worth chiseling into marble. When the upper class understands metaphor while the masses require literality, freedom declines.

The surest way to understand metaphor is to read literature and history and think about it deeply, especially about how it applies to modern realities (which is why classrooms were once dedicated to discussion about important books, as mentioned above).

This is why the university phrase “I majored in literature, science, or history” is a middle-class expression while the upper class prefers to say, “I read literature, science, or history at X University.”

The differences here are striking: the upper class never believes it has actually “majored” a topic, while the middle class can seldom claim to have seriously “read” all the great works in any important academic field.

This fundamental difference in education remains a cause of the widening gap between upper and middle class. Indeed, education is a major determining factor of the contemporary (and historical) class divide. It is the ability to think metaphorically (to in fact consider everything both literally and metaphorically) and to automatically seek out and consider the various potential meanings of all things, that most separates the culture of the “haves” from the global “have-nots.”

The Ideology Barrier

In politics, the far left and far right—including, most notably right now, the environmental movement and the tea parties—significantly limit their own growth by staying too literal.

This comes across to most Americans as ineffectively rigid, intolerant, naïve, and even ideological.

The fact that most environmentalists and tea partiers are genuinely passionate and sincere is not a plus in the eyes of many people as long as such activists are seen to be humorless and even angry.

Such activists may not in fact be humorless and angry, but when they seem to be these things, they diminish their ability to build rapport with anyone that does not already understand their point of view.

Feminism once carried these same negatives, but recently gained more mainstream understanding once feminist thinkers moved past literality and used art and entertainment to gain positive support. The gay-lesbian community made the same transition in the past two decades, and environmentalism is starting to make this shift as well (witness the recent hubbub over Cars III).

Whether you agree or disagree with these political movements is not the point; they gain mainstream support by portraying themselves as relaxed, happy, caring and likeable people, and by sharing their principles by telling a story.

False Starts, or, Failed Expectations

President Bush attempted to effect such a change in the Republican Party with his emphasis on Compassionate Conservatism, but this theme disappeared after 9/11.

President Obama exuded this relaxed optimism through the 2008 campaign and several months into his presidency, becoming a symbol of change and leadership to America’s youth (who hadn’t had a real political hero since Ronald Reagan). The president’s cult-hero status disappeared when the Obama Administration’s literality (not liberality) was eventually interpreted as robotic, smug and even defensive.

The White House’s big-spending agenda in 2009-2010, coming on the heels of over seven years of Republican-led overspending, sparked a tea party revolt. It also drove most independents to the right, not because they supported right-wing policies but rather because independents tend to understand metaphor: they saw that the Obama agenda was primarily about bigger government and only secondarily about real change.

To put this as literally as possible, President Obama desired lasting change in Washington, but he cared even more about certain policies which required massive government spending.

There are true supporters of real freedom on all sides of the political table: Democratic, Republican, independent, blue, red, green, tea party, etc. They would all do well to spread deep, quality, creative, artistic and metaphorical thinking in our society.

As Lord Brougham taught:

“Education makes a people easy to lead, but difficult to drive; easy to govern, but impossible to enslave.”

He was speaking not of modern specialized job training but of reading the greatest books of mankind. Leaders are readers, and so are free nations.

Symbolism, Nuance and the Deficits of Literalism

As long as metaphor is missing in our dialogue—not to mention much in our prevailing educational offerings—the people will be continually frustrated by their political leaders.

Campaigns succeed through symbolism, especially metaphor, while daily governance naturally requires a major dose of literalism. Sometimes a significant crisis swings the nation into a period of metaphor, but this mood seldom lasts much longer than the crisis itself.

The most effective leaders (e.g. Washington, Jackson, Lincoln, the Roosevelts and Reagan) are able to communicate a metaphor of American grand purpose even while they govern literally. For example, the Jeffersonian “era” lasted for decades beyond his term of office, building on the American mind captured by the metaphor of freedom; John Adams’ literalism hardly carried him through his one term.

While some of this is the responsibility of the leader, it is ultimately the duty of the people to think in metaphor and understand the big themes and hidden nuances behind government proposals and policies.

In this regard, groups such as environmentalists and tea parties seem to really understand the major trends and are courageously making their voice heard. Unfortunately for their goals, they have yet to effectively present their messages using metaphor. People tend to see them, as mentioned above, as humorless, angry and ideologically rigid.

The irony is rich, because most Americans actually support both a higher level of environmental consciousness and a major increase of government fiscal responsibility. In literal terms, many Americans agree with a large number of green and tea party proposals even as they say they dislike the “environmentalists” and the “tea parties.”

Again, the problem is that these groups tend to emphasize only the literal.

Such examples may be interesting, but the real problem for the future of American freedom is a populace that doesn’t naturally think through everything in a metaphorical way.

A free society only stays as free—and as prosperous—as its electorate allows.

When a nation has been educated to separate its thinking, it tends to be easily swayed by an upper class that understands and uses metaphor—in politics, economics, marketing, media, and numerous walks of life. It becomes subtly enslaved to experts, because, quite simply, it believes what the experts say.

Alternate Timeline of Literalism

If the American founding generation had so believed the experts, it would have stuck with Britain, would never have bothered reading the Federalist Papers, and would have left governance to the upper class.

The capitol would probably be New York City, and the middle class would have remained small. We would be a more aristocratic society, with an entirely different set of laws for the wealthy than the rest.

Such forays into theoretical history are hardly provable, but one thing is clear: American greatness is soundly based on a citizenry that thought independently, creatively, innovatively and metaphorically. The educational system encouraged such thinking, and adult discourse continued it throughout the citizen’s life.

Great education teaches one to listen to the experts, and to then take one’s own counsel on the important decisions.

Indeed, such education prepares the adult to weigh the words of experts and all other sources of knowledge and then to choose wisely.

Sit in chair; open book. Read.

Metaphor matters. Metaphorical thinking is vital to freedom. The classics are the richest vein of metaphorical and literal thinking.

Every nation that has maintained real freedom has been a nation of readers—readers of the great books. Freedom is in decline precisely because reading the great classics is in decline. Fortunately, every regular citizen can easily do something to fix this problem.

The books are on our shelves.

For more on this topic, listen to “The Freedom Crisis.”

Click here for details >>

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Aristocracy &Arts &Blog &Culture &Current Events &Education &Featured &Generations &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Politics