The Social Animal

April 20th, 2011 // 7:31 am @ Oliver DeMille

A review of the book The Social Animal: A Story of Love, Character and Achievement by David Brooks

There are at least three major types of writing. The first might be called Shakespeare’s method, which includes the telling of stories with deep symbolic and archetypal lessons. Many of the great world religious texts used this approach. The Greeks referred to this as poetry, though the meaning of “poetry” is much more limited in modern usage. In the contemporary world we often call this type of writing fiction, though this is a misnomer since the stories used are not actually untrue—they are, many of them, literally true, and nearly all of them are symbolically true. This could also be called the Inspirational style of writing.

There are at least three major types of writing. The first might be called Shakespeare’s method, which includes the telling of stories with deep symbolic and archetypal lessons. Many of the great world religious texts used this approach. The Greeks referred to this as poetry, though the meaning of “poetry” is much more limited in modern usage. In the contemporary world we often call this type of writing fiction, though this is a misnomer since the stories used are not actually untrue—they are, many of them, literally true, and nearly all of them are symbolically true. This could also be called the Inspirational style of writing.

A second kind of writing can be summarized as Tocqueville’s method, or the philosopher’s style. Called prose, non-fiction, or editorializing, this type of literature consists of the author sharing her views, thoughts, questions, analyses and conclusions. Writers in this style see no need to document or prove their points, but they do make a case for their ideas. This way of writing gave the world many of the great classics of human history—in many fields of thought spanning the arts, sciences, humanities and practical domains. This writing is Authoritative in style, meaning that the author is interested mostly in ideas (rather than proof or credibility) and writes as her own authority on what she is thinking.

The third sort of writing, what I’ll call Einstein’s method, attempts to prove its conclusions using professional language and appealing to reason, experts or other authority. Most scientific works, textbooks, and research-based books on a host of topics apply this method. The basis of such writing is to clearly show the reader the sources of assumptions, the progress of the author’s thinking, and the basis behind each conclusion. Following the scientific method, this modern “Objective” style of writing emphasizes the credibility of the conclusions—based on the duplicable nature of the research and the rigorous analysis and deduction. There are few leaps of logic in this kind of prose.

Each type of writing has its masters, and all offer valuable contributions to the great works of human literature. This is so obvious that it hardly needs to be said, but we live in a world where the third, Objective, style of writing is the norm and anything else is often considered inferior. Such a conclusion, ironically, is not a scientifically proven fact. Indeed, how can science prove that anything open to individual preference and taste is truly “best?” For example, such greats as Churchill, Solzhenitsyn and Allan Bloom (author of The Closing of the American Mind) have shown that “Tocqueville’s” style is still of great value in modern times—as do daily op eds in our leading newspapers and blogs. Likewise, our greatest plays, movies and television programs demonstrate that the Shakespearean method still has great power in our world.

That said, David Brooks’ new book The Social Animal: A Story of Love, Character and Achievement manages to combine all three styles in one truly moving work. I have long considered Brooks one of my favorite authors. I assigned his book Bobos in Paradaise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There as an undergraduate and graduate college text for several years, and I have recommended his book On Paradise Drive to many students and executives who wanted to understand American and modern culture. In one of the best descriptions of our society ever written, he outlined the new realities experienced by the “average” American citizen, who he called “Patio Man.” I have also enjoyed many of his editorials in The New York Times—and the ongoing, albeit unofficial and indirect, “debate” between his columns and those of Thomas L. Friedman, Paul Krugman, George Will and, occasionally, Peggy Noonan.

The Social Animal is, in my opinion, his best work to date. In fact, it is downright brilliant. I am not suggesting that it approaches Shakespeare, of course. But who does? Still, the stories in The Social Animal flow like Isaac Asimov meets Ayn Rand. It doesn’t boast deep scientific technical writing, as Brooks himself notes. Indeed, Brooks doesn’t even attempt to produce a great Shakespearean or scientific classic. But he does effectively weave the three great styles of writing together, and in the realm of philosophical writing this book is similar to Tocqueville’s Democracy in America. The content of the book, in fact, is as close as we may ever see to a 21st century update to Tocqeville (1830s) and Bryce (1910s).

I know this is high praise, and in our modern era with its love of objective analysis, such strong language is suspect in “educated” circles. But my words are not hyperbole. This is an important book. It is one of the most important books we’ve seen in years—probably since Fareed Zakaria’s The Post-American World or Daniel Pink’s A Whole New Mind. This book is in the same class as Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind, Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations, Strauss and Howe’s The Fourth Turning, or Philip Bobbitt’s The Shield of Achilles. It is as significant as any article in Foreign Affairs since Richard Gardner’s writings. It reads like Steven Pinker channelling Alexis de Tocqueville. The language is, well, beautiful, but beautiful in the modern sense, like the writings of Laura Munson or Sandra Tsing Loh.

The book also manages to bridge political views—I think liberals will find it moving and conservatives will find it convincing. It is not exactly Centrist, but neither is it patently Right nor Left. It will appeal to independents and people from all political perspectives. If it has a political leaning, it is the party of Common Sense—backed by meticulous research.

Moreover, The Social Animal clouds typical publishing stereotypes. I’m not sure where big bookstores will shelve it. It is a book on culture, politics, education, and career. It is a book about entertainment, marriage and language. It is about the upper, middle and lower classes in modern American society, how they interrelate and what challenges are ahead as they clash. It is about current events and future challenges. It is, above all, a book about success. It goes well beyond books on Habits or The Secret or even “Acres of Diamonds.”

As Brooks himself put it:

“Over the centuries, zillions of books have been written about how to succeed. But these tales are usually told on the surface level of life. They describe the colleges people get into, the professional skills they acquire, the conscious decisions they make, and the tips and techniques they adopt to build connections and get ahead. These books often focus on an outer definition of success, having to do with IQ, wealth, prestige, and worldly accomplishments.

“This story [The Social Animal] is told one level down. This success story emphasizes the role of the inner mind—the unconscious realm of emotions, intuitions, biases, longings….

“…we are not primarily the products of our conscious thinking. We are primarily the products of thinking that happens below the level of awareness.”

Brooks argues:

“The research being done today reminds us of the relative importance of emotion over pure reason, social connections over individual choice, character over IQ, emergent, organic systems over linear, mechanistic ones, and the idea that we have multiple selves over the idea that we have a single self.”

The book deals with such intriguing topics as:

- Modern dating and courtship

- Today’s marriages and what makes them succeed—or not

- The scientific versus popular views of child development

- Cultural trends such as global-warming awareness assemblies in high schools

- The scientific foundations of violence

- The kind of decision-making that leads to success versus mediocrity and failure

- A veritable manual for success in college

- The powerful leadership techniques of priming, anchoring, framing, limerance, fractals, metis and multiparadigm teams, among others (it is worth reading the book just for this)

- How to “ace” job interviews

- The new phases of life progression

- Effectively starting a new business—the steps, techniques, values and needed character traits

- Leadership in the modern corporation

- How to win a revolution by only making a call for small reforms

- The effectiveness of a talent for oversimplification

- The supreme power of a life’s viewpoint

The Social Animal struck a personal note with me because it brilliantly describes the true process of great mentoring that more of our teachers need to adopt and that I wrote about with Tiffany Earl in our book The Student Whisperer. I have seldom seen truly great teaching described better.

This book is primarily about success—specifically success in our complex modern world—but at a deeper level it is about happiness. Brooks writes:

We still have admissions committees that judge people by IQ measures and not by practical literacy. We still have academic fields that often treat human beings as rational utility-maximizing individuals. Modern society has created a giant apparatus for the cultivation of the hard skills, while failing to develop the moral and emotional faculties down below. Children are coached on how to jump through a thousand scholastic hoops. Yet by far the most important decisions they will make are about whom to marry and whom to befriend, what to love and what to despise, and how to control impulses. On these matters, they are almost entirely on their own. We are good at talking about material incentives, but bad about talking about emotions and intuitions. We are good at teaching technical skills, but when it comes to the most important things, like character, we have almost nothing to say.

The book, like any true “classic” (and I am convinced this will be one), is deep and broad. It includes such gems as:

- “The food at their lunch was terrible, but the meal was wonderous.”

- “For example, six-month-old babies can spot the different facial features of different monkeys, even though, to adults, they all look the same.”

- In his high school, “…life was dominated by a universal struggle for admiration.”

- “The students divided into the inevitable cliques, and each clique had its own individual pattern of behavior.”

- “Fear of exclusion was his primary source of anxiety.”

- “Erica decided that in these neighborhoods you could never show weakness. You could never back down or compromise.”

- “In middle class country, children were raised to go to college. In poverty country they were not.”

- Jim Collins “…found that many of the best CEOs were not flamboyant visionaries. They were humble, self-effacing, diligent, and resolute souls who found one thing they were really good at and did it over and over again. They did not spend a lot of time on internal motivational campaigns. They demanded discipline and efficiency.”

- “Then a quiet voice could be heard from the other end of the table. ‘Leave her alone.’ It was her mother. The picnic table went silent.”

- “Erica resolved that she would always try to stand at the junction between two mental spaces. In organizations, she would try to stand at the junction of two departments, or fill in the gaps between departments.”

- “School asks students to be good at a range of subjects, but life asks people to find one passion that they will do forever.”

- “His missions had been clearly marked: get good grades, make the starting team, make adults happy. Ms. Taylor had introduced a new wrinkle into his life—a love of big ideas.”

- “…if Steve Jobs had come out with an iWife, they would have been married on launch day.”

- “Epistemological modesty is the knowledge of how little we know and can know.”

There are so many more gems of wisdom. For example, Brooks notes that in current culture there is a new phase of life. Most of today’s parents and grandparents grew up in a world with four life phases, including “childhood, adolescence, adulthood and old age.” Today’s young will experience at least six phases, Brooks suggests: childhood, adolescence, odyssey, adulthood, active retirement, and old age.

While many parents expect their 18- and 19-year-old children to go directly from adolescence to the adult life of leaving home and pursuing their own independent life and a marriage relationship, their children are surprising (and confusing) them by embracing their odyssey years: living at home, then wandering, then back home for a time, taking a long time to “play around” with their education before getting serious about preparing for a career, and in general enjoying their youthful freedom. Most parents are convinced they’re kids are wasting their lives when in fact this is the new normal.

The odyssey years actually make a lot of sense. The young “…want the security and stability adulthood brings, but they don’t want to settle into a daily grind. They don’t want to limit their spontaneity or put limits on their dreams.” Parents can support this slower pace with two thoughts: 1) the kids usually turn out better because they don’t force themselves to grow up too fast like earlier generations did, and 2) the parents get to enjoy a similar kind of relaxed state in the “active retirement phase.”

Most odysseys pursue life in what Brooks calls The Group—a small team of friends who help each other through this transition. Members of a Group talk a lot, play together, frequently engage entrepreneurial or work ventures with each other, and fill the role of traditional families during this time of transition. Even odysseys who live at home for a time usually spend much of their time with their Group.

This book is full of numerous other ideas, stories, studies, and commentaries. It is the kind of reading that you simply have to mark up with a highlighter on literally every page.

Whether you agree or disagree with the ideas in this book—or, hopefully, both—it is a great read. Not a good read, but a great one. Some social conservatives may dislike certain things such as the language used by some characters or the easy sexuality of some college students, and some liberals may question the realistic way characters refuse to accept every politically-correct viewpoint in society—but both are accurate portrayals of many people in our current culture.

The Social Animal may not remain on the classics list as long as Democracy in America, but it could. At the very least, it is as good a portrayal of modern society as Rousseau’s Emile was in its time. It provides a telling, accurate and profound snapshot of American life at the beginning of the 21st Century. Reading it will help modern Americans know themselves at a much deeper level.

This is a book about many things, including success and happiness as mentioned above. But it is also a classic book on freedom, and on how our society defines freedom in our time. As such, it is an invaluable source to any who care about the future of freedom. Read this book to see where we are, where we are headed, and how we need to change. The Social Animal is required reading for leaders in all sectors and for people from all political persuasions who want to see freedom flourish in the 21st century.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Blog &Book Reviews &Community &Culture &Current Events &Education &Entrepreneurship &Family &Generations &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Postmodernism &Service &Statesmanship &Tribes

Is America a Democracy, Republic, or Empire?

April 20th, 2011 // 7:09 am @ Oliver DeMille

Some in Washington are fond of saying that certain nations don’t know how to do democracy.

Anytime a nation breaks away from totalitarian or authoritarian controls, these “experts” point out that the people aren’t “prepared” for democracy.

But this is hardly the point.

A nation where the people aren’t prepared for democracy–but where a strong leader is prepared for tyranny–is still better off as a democracy.

A nation where the people aren’t prepared for democracy but where an elite class is prepared for aristocracy is still better off as a democracy.

A nation where the people aren’t prepared for democracy but where a socialist or fundamentalist religious bureaucracy is prepared to rule is still better off as a democracy.

Whatever the people’s inadequacies, they will do better than the other, class-dominant forms of government.

Winston Churchill was right:

“Democracy is the worst form of government–except for all those others that have been tried.”

False Democracy

When I say “democracy,” I am of course not referring to a pure democracy where the masses make every decision; this has always turned to mob rule through history.

Of Artistotle’s various types and styles of democracy, this was the worst. The American founders considered this one of the least effective of free forms of government.

Nor do I mean a “socialist democracy” as proposed by Karl Marx, where the people elect leaders who then exert power over the finances and personal lives of all citizens.

Whether this type of government is called democracy (e.g. Social Democrats in many former Eastern European nations) in the Marxian sense or a republic (e.g. The People’s Republic of China, The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics–USSR, etc.), it amounts to the same oligarchic model of authoritarian rule.

Marx used the concept of democracy–he called it “the battle for democracy”–to argue for the working classes to rise up against the middle and upper classes and take back their power.

Ironically, he believed the masses incapable of such leadership, and felt that a small group of elites, the “vanguard”, would have to do the work of the masses for them.

This argument assumes an oligarchic view of the world, and the result of attempted Marxism has nearly always been dictatorial or oligarchic authoritarianism.

In this attitude Marx follows his mentor Hegel, who discounted any belief in the power or wisdom of the people as wild imaginings (see Mortimer Adler’s discussion on “Monarchy” in the Syntopicon).

The American founders disagreed entirely with this view.

A Democratic Republic

The type of democracy we need more of in the world is constitutional representative democracy, with:

A written constitution that separates the legislative, executive and judicial powers. Limits all with checks and balances, and leaves most of the governing power in the hands of the people and local and regional, rather than national, government institutions.

In such a government, the people have the power to elect their own representatives who participate at all levels. Then the people closely oversee the acts of government.

One other power of the people in a constitutional representative democratic republic is to either ratify or reject the original constitution.

Only the support of the people allows any constitution to be adopted (or amended) by a democratic society.

The American framers adopted Locke’s view that the legislative power was closest to the people and should have the sole power over the nation’s finances.

Thus in the U.S. Constitution, direct representatives of the people oversaw the money and had to answer directly to the people every two years.

Two Meanings of “Democracy”

There are two ways of understanding the term democracy. One is as a governmental form–which is how this article has used the word so far. The other is as a societal format.

There are four major types of societies:

- A chaotic society with no rules, laws or government

- A monarchical society where one man or woman has full power over all people and aspects of the society

- An aristocratic society where a few people–an upper class–control the whole nation

- A democratic society where the final say over the biggest issues in the nation comes from the regular people

As a societal form, democracy is by far the best system.Montesquieu, who was the source most quoted at the American Constitutional Convention, said:

“[Democracy exists] when the body of the people is possessed of the supreme power.”

In a good constitutional democracy, the constitution limits the majority from impinging upon the inalienable rights of a minority–or of anyone at all.

Indeed, if a monarchical or aristocratic society better protects the rights of the people than a democratic nation, it may well be a more just and free society.

History has shown, however, that over time the people are more likely to protect their rights than any royal family or elite class.

When the many are asked to analyze and ratify a good constitution, and then to protect the rights of all, it turns out they nearly always protect freedom and just society better than the one or the few.

It is very important to clarify the difference between these two types of democracy–governmental and societal.

For example, many of the historic Greek “democracies” were governmental democracies only. They called themselves democracies because the citizens had the final say on the governmental structure and elections–but only the upper class could be citizens.

Thus these nations were actually societal aristocracies, despite being political democracies.

Plato called the societal form of democracy the best system and the governmental format of democracy the worst.

Clearly, knowing the difference is vital.

Aristotle felt that there are actually six major types of societal forms.

A king who obeys the laws leads a monarchical society, while a king who thinks he is above the law rules a tyrannical society.

Likewise, government by the few can either have different laws for the elite class or the same laws for all people, making oligarchy or aristocracy.

In a society where the people are in charge, they can either rule by majority power (he called this democracy) or by wise laws, protected inalienable rights and widespread freedom (he called this “mixed” or, as it is often translated, “constitutional” society).

Like Plato, Aristotle considered the governmental form of democracy bad, but better than oligarchy or tyranny; and he believed the societal form of democracy (where the people as a mass generally rule the society) to be good.

Democracy or Republic?

The authors of The Federalist Papers tried to avoid this confusion about the different meanings of “democracy” simply by shortening the idea of a limited, constitutional, representative democracy to the term “republic.”

A breakdown of these pieces is enlightening:

- Limited (unalienable rights for all are protected)

- Constitutional (ratified by the people; the three major powers separated, checked and balanced)

- Representative (the people elect their leaders, using different constituencies to elect different leaders for different governmental entities–like the Senate and the House)

- Democracy (the people have the final say through elections and through the power to amend the constitution)

The framers required all state governments to be this type of republic, and additionally, for the national government to be federal (made up of sovereign states with their own power, delegating only a few specific powers to the national government).

When we read the writings of most of the American founders, it is helpful to keep this definition of “republic” in mind.

When they use the terms “republic” or “a republic” they usually mean a limited, constitutional, representative democracy like that of all the states.

When they say “the republic” they usually refer to the national-level government, which they established as a limited, constitutional, federal, representative democracy.

At times they shorten this to “federal democratic republic” or simply democratic republic.

Alexander Hamilton and James Wilson frequently used the term “representative democracy,” but most of the other founders preferred the word “republic.”

A Global Problem

In today’s world the term “republic” has almost as many meanings as “democracy.”

The term “democracy” sometimes has the societal connotation of the people overseeing the ratification of their constitution. It nearly always carries the societal democracy idea that the regular people matter, and the governmental democracy meaning that the regular people get to elect their leaders.

The good news is that freedom is spreading. Authoritarianism, by whatever name, depends on top-down control of information, and in the age of the Internet this is disappearing everywhere.

More nations will be seeking freedom, and dictators, totalitarians and authoritarians everywhere are ruling on borrowed time.

People want freedom, and they want democracy–the societal type, where the people matter. All of this is positive and, frankly, wonderful.

The problem is that as more nations seek freedom, they are tending to equate democracy with either the European or Asian versions (parliamentary democracy or an aristocracy of wealth).

The European parliamentary democracies are certainly an improvement over the authoritarian states many nations are seeking to put behind them, but they are inferior to the American model.

The same is true of the Asian aristocratic democracies.

Specifically, the parliamentary model of democracy gives far too much power to the legislative branch of government, with few separations, checks or balances.

The result is that there are hardly any limits to the powers of such governments. They simply do whatever the parliament wants, making it an Aristotelian oligarchy.

The people get to vote for their government officials, but the government can do whatever it chooses–and it is run by an upper class.

This is democratic government, but aristocratic society. The regular people in such a society become increasingly dependent on government and widespread prosperity and freedom decrease over time.

The Asian model is even worse. The governmental forms of democracy are in place, but in practice the very wealthy choose who wins elections, what policies the legislature adopts, and how the executive implements government programs.

The basic problem is that while the world equates freedom with democracy, it also equates democracy with only one piece of historical democracy–popular elections.

Nations that adopt the European model of parliamentary democracy or the Asian system of aristocratic democracy do not become societal democracies at all–but simply democratic aristocracies.

Democracy is spreading–if by democracy we mean popular elections; but aristocracy is winning the day.

Freedom–a truly widespread freedom where the regular people in a society have great opportunity and prosperity is common–remains rare around the world.

The Unpopular American Model

The obvious solution is to adopt the American model of democracy, as defined by leading minds in the American founding: limited, constitutional, representative, federal, and democratic in the societal sense where the regular people really do run the nation.

Unfortunately, this model is currently discredited in global circles and among the world’s regular people for at least three reasons:

1. The American elite is pursuing other models.

The left-leaning elite (openly and vocally) idealize the European system, while the American elite on the right prefers the Asian structure of leadership by wealth and corporate status.

If most of the intelligentsia in the United States aren’t seeking to bolster the American constitutional model, nor the elite U.S. schools that attract foreign students on the leadership track, it is no surprise that freedom-seekers in other nations aren’t encouraged in this direction.

2. The American bureaucracy around the world isn’t promoting societal democracy but rather simple political democracy–popular elections have become the entire de facto meaning of the term “democracy” in most official usage.

With nobody pushing for limited, constitutional, federal, representative democratic republics, we get what we promote: democratic elections in fundamentally class-oriented structures dominated by elite upper classes.

3. The American people aren’t all that actively involved as democratic leaders.

When the U.S. Constitution was written, nearly every citizen in America was part of a Town Council, with a voice and a vote in local government. With much pain and sacrifice America evolved to a system where every adult can be such a citizen, regardless of class status, religious views, gender, race or disability.

Every adult now has the opportunity to have a real say in governance. Unfortunately, we have over time dispensed with the Town Councils of all Adults and turned to a representative model even at the most local community and neighborhood level.

As Americans have ceased to participate each week in council and decision-making with all adults, we have lost some of the training and passion for democratic involvement and become more reliant on experts, the press and political parties.

Voting has become the one great action of our democratic involvement, a significant decrease in responsibility since early America.

We still take part in juries–but now even that power has been significantly reduced–especially since 1896.

In recent times popular issues like environmentalism and the tea parties have brought a marked increase of active participation by regular citizens in the national dialogue.

Barack Obama’s populist appeal brought a lot of youth into the discussion. The Internet and social media have also given more power to the voice of the masses.

When the people do more than just vote, when they are involved in the on-going dialogue on major issues and policy proposals, the society is more democratic–in the American founding model–and the outlook for freedom and prosperity brightens.

The Role of the People

Human nature being what it is, no people of any nation may be truly prepared for democracy.

But–human nature being what it is–they are more prepared to protect themselves from losses of freedom and opportunity than any other group.

Anti-democratic forces have usually argued that we need the best leaders in society, and that experts, elites and those with “breeding,” experience and means are most suited to be the best leaders.

But free democratic societies (especially those with the benefits of limited, constitutional, representative, and locally participative systems) have proven that the right leaders are better than the best leaders.

We don’t need leaders (as citizens or elected officials) who seem the most charismatically appealing nearly so much as we need those who will effectively stand for the right things.

And no group is more likely to elect such leaders than the regular people.

It is the role of the people, in any society that wants to be or remain free and prosperous, to be the overseers of their government.

If they fail in this duty, for whatever reason, freedom and widespread prosperity will decrease. If the people don’t protect their freedoms and opportunities, despite what Marx thought, nobody will.

No vanguard, party or group of elites or experts will do as much for the people as they can do for themselves. History is clear on this reality.

We can trust the people, in America and in any other nation, to promote widespread freedom and prosperity better than anyone else.

Two Challenges

With that said, we face at least two major problems that threaten the strength of our democratic republic right now in the United States.

First, only a nation of citizen-readers can maintain real freedom. We must deeply understand details like these:

- The two meanings of democracy

- The realities and nuances of ideas such as: limited, constitutional, federal, representative, locally participative, etc.

- The differences between the typical European, Asian, early American and other models competing for support in the world

- …And so on

In short, we must study the great classics and histories to be the kind of citizen-leaders we should be.

The people are better than any other group to lead us, as discussed above, but as a people we can know more, understand more, and become better leaders.

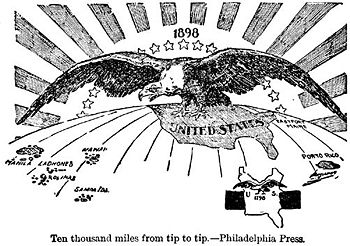

As George Friedman has argued, we now control a world empire larger than any in history, whether we want to or not.

Yet a spirit of democratic opportunity, entrepreneurial freedom, inclusive love of liberty, freedom from oppressive class systems, and promotion of widespread prosperity is diametrically opposed to the arrogant, selfish, self-elevating, superiority-complex of imperialism.

This very dichotomy has brought down some of the greatest free nations of history.

On some occasions this challenge turned the home nation into an empire, thus killing the free democratic republic (e.g. Rome).

Other nations lost their power in the world because the regular people of the nation did not reconcile their democratic beliefs with the cruelty of imperial dominance and force (e.g. Athens, ancient Israel).

At times the colonies of an empire used the powerful democratic ideals of the great power against them and broke away.

At times the citizens of the great power refused to support the government in quelling rebellions with which they basically agreed (e.g. Great Britain and its relations with America, India, and many other former colonies).

Many of the great freedom thinkers of history have argued against empire and for the type of democratic republic the American framers established–see for example Herodotus, Thucydides, Aristotle, the Bible, Plutarch, Tacitus, Augustine, Montaigne, Locke, Montesquieu, Gibbon, Jefferson, The Declaration of Independence, and Madison, among others.

The Federalist mentions empire or imperialism 53 times, and not one of the references is positive.

In contrast, the main purpose of the Federalist Papers was to make a case for a federal, democratic republic.

Those who believe in American exceptionalism (that the United States is an exception to many of the class-oriented patterns in the history of nations) now face their greatest challenge.

Will America peacefully and effectively pull back from imperialism and leave dozens of nations successfully (or haltingly) running themselves without U.S. power?

Will it set its best and brightest to figuring out how this can be done? Or to increasing the power of empire?

Empire and Freedom

Some argue that the United States cannot divest itself of empire without leaving the world in chaos.

This is precisely the argument nearly all upper classes, and slave owners, make to justify their unprincipled dominance over others.

The argument on its face is disrespectful to the people of the world.

Of course few people are truly prepared to run a democracy–leadership at all levels is challenging and at the national level it is downright overwhelming.

But, again–the people are more suited to oversee than any other group.

And without the freedom to fail, as Adam Smith put it, they never have the dynamic that impels great leaders to forge ahead against impossible odds. They will never fly unless the safety net is gone.

The people can survive and sometimes even flourish without elite rule, and the world can survive and flourish without American empire.

A wise transition is, of course, the sensible approach, but the arrogance of thinking that without our empire the world will collapse is downright selfish–unless one values stability above freedom.

How can we, whose freedom was purchased at the price of the lives, fortunes and sacred honor of our forebears, and defended by the blood of soldiers and patriots in the generations that followed, argue that the sacrifices and struggles that people around the world in our day might endure to achieve their own freedom and self- determination constitute too great a cost?

The shift will certainly bring major difficulties and problems, but freedom and self-government are worth it.

The struggles of a free people trying to establish effective institutions through trial, error, mistakes and problems are better than forced stability from Rome, Madrid, Beijing, or even London or Washington.

America can set the example, support the process, and help in significant ways–if we’ll simply get our own house in order.

Our military strength will not disappear if we remain involved in the world without imperial attitudes or behaviors. We can actively participate in world affairs without adopting either extreme of isolationism or imperialism.

Surely, if the world is as dependent on the U.S. as the imperial-minded claim, we should use our influence to pass on a legacy of ordered constitutional freedom and learning self-government over time rather than arrogant, elitist bureaucratic management backed by military might from afar.

If Washington becomes the imperial realm to the world, it will undoubtedly be the same to the American people. Freedom abroad and at home may literally be at stake.

The future will be significantly impacted by the answers to these two questions:

Will the American people resurrect a society of citizen readers actively involved in daily governance?

Will we choose our democratic values or our imperialistic attitudes as our primary guide for the 21st Century?

Who are we, really?

Today we are part democracy, part republic, and part empire.

Can we find a way to mesh all three, even though the first two are fundamentally opposed to the third?

Will the dawn of the 22nd Century witness an America free, prosperous, strong and open, or some other alternative?

If the United States chooses empire, can it possibly retain the best things about itself?

Without the Manifest Destiny proposed by the Founders, what alternate destiny awaits?

Above all, will the regular citizens–in American and elsewhere–be up to such leadership?

No elites will save us. It is up to the people.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Constitution &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History &Leadership &Liberty &Politics &Postmodernism &Statesmanship

The Declining American Dream

January 31st, 2011 // 9:55 am @ Oliver DeMille

We still hear about the American Dream. But more and more it seems we’re in a Matrix-like dream state where our perceptions are being manipulated. It’s actually a pretty common plot in cinema: The Minority Report, The Sixth Day, Total Recall, Inception, The Adjustment Bureau and others riff on this theme. We’re living in a reality out-of-synch with some truth we’ve lost, and we don’t even realize it. Somehow our collective memory and our assumptions of “normal” are slowly morphing, and our definition of the American Dream at present is so far removed from the original concept as to be a pretty fair Doublespeak[i] idiom.

Back when the Cleavers[ii] and even the Bradys[iii] were the icons of American families, what was the definition of “The American Dream”? What did it mean to be “middle class”? There are some features of it that were fairly well accepted once upon a time:

1. Home Ownership I

Perhaps the most traditional measure of middle class and the American Dream is the ability for every man to be the king of his own castle. In this the U.S. was a beacon to the world, and other countries even began to adopt the value that every person might aspire to own his own dwelling. The historical and sociological significance of home ownership includes the moral and political empowerment of being “landed,” and affiliation with the natural aristocracy. Homeowners were believed to have a deeper sense of responsibility to invest in their property improvement, an elevated pride in and loyalty to their neighborhoods and communities, and a higher commitment to the good of society in general.

2. Home Ownership II

Now we have to dig a little deeper into our genetic memory. Home ownership a generation or three ago meant not only that you weren’t renting from somebody else, but after a maximum of thirty years in your home you weren’t renting it from the bank, either. A 30-year mortgage left the likes of Ward and June Cleaver without a house payment right about when the grandkids started showing up, and they were able to be a boon to their young married children as they were starting out. If the idea of Home Ownership I as a definition of “The American Dream” is still generally accepted (and I believe it is), the Home Ownership II definition has been deleted from our collective memory. Not only do we have a 30-year mortgage that gets refinanced ad infinitum, but we have seconds on our vanishing equity—and our seniors are living on the funds derived from reverse mortgages.

3. One Income

For the Cleavers and the Bradys, Home Ownership I and II were accomplished on one income. Dad had evenings and weekends for leisure; mom could volunteer with the PTA and community service organizations. Both could participate in book clubs, bowling leagues, gardening and other vocations. The Women’s Lib movement sent the modern woman into the workforce by choice; now Home Ownership II is entirely out of reach for the middle class, and Home Ownership I requires a minimum of two incomes—and often multiple jobs for an individual worker—in order to be a reality.

4. Two Cars

The family had a car—and later two. They were American made with pride, and they were built to last. Paid with cash from savings, or with a little help from the local bank, they were paid off long before they were sent to the salvage yard. Some families even scandalized the neighbors by giving each of their teens a car as soon as they were legal to drive.

5. College for Kids

Part of the understanding for middle class families was that they would be able to pay for their kids to get a college education. Now all that’s left of that understanding is the guilt for failing to live up to it. No one seriously expects one-income families to be able to pay off the house and cars and simultaneously send several kids to the University. Scholarships, loans, grants and lingering debt into the career years are now the means for those who want a college education.

6. Discretionary Income

With all of the above, it was still an expectation that a married couple could live within their means and have savings, investment, yearly vacations with the whole family at some destination spot, and still have a few dimes to rub together at the end of the month.

7. Retirement

Ah, and after all this came the golden years. The Cleavers could now spend their expanded leisure time, afforded by an empty nest and the retirement from the company (complete with gold watch honors), in community service and nurturing the rising generation. They had savings, investments and retirement income to fall back on, a house and car paid free and clear, and the greatest resource: Leisure Time. They were elders in their community, and relied upon for wisdom.

The percentage of families enjoying these luxuries shrinks every year. Where did our American Dream go? Somehow, point by point, it has slipped away from us, and taken with it our definition of “middle class.” Would that we could wake up and reclaim the best of that dream; instead, we’ve awakened to a reality where our elusive American Dream is just out of reach; and these seven points that were once considered the legacy of any hard-working family are being deleted from our list of aspirations. If they are middle class expectations, the majority of America is no longer middle class.

[For a follow-up article on the how and why the middle class is shrinking, and how to reverse the trend, read Oliver’s article, “The Rule of Leisure,” featured in the February 2011 monthly newsletter for The Center for Social Leadership.

[i] See Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-four.

[ii] From the 1950 – 60s classic sitcom about the traditional nuclear family of Ward and June Cleaver, “Leave it to Beaver”.

[iii] From the classic 1970s sitcom about the non-traditional nuclear family of Mike and Carol Brady, “The Brady Bunch”.

Category : Blog &Community &Culture &Economics &Entrepreneurship &Family &Generations &Politics &Postmodernism &Producers &Prosperity

The New Man

December 23rd, 2010 // 4:00 am @ Oliver DeMille

I wrote in an earlier review of several recent articles and books on “the end of men.” Such writings sparked a lot of discussion on the national scene, mostly among women.

Men, it seems, aren’t paying much attention to such things. Where men do take exception to the predictions and statistics about man’s falling value to society, it has mostly come in the tone of irony.

For example, Colin McEnroe slaps back in the September 2010 issue of Men’s Health with arguments like:

“But listen up, ladies: The buttons on that remote aren’t going to push themselves.”

“They would miss us, right? There would be subtle repercussions. For example…jar opening, wasp-nest nuking, rodeo riding…knife fights in malls…”

“Women are still free to seek our elimination, of course, but my advice is to keep a small number of us—300 or 400—in some kind of zoo, for breeding purposes. Like albino alligators, we may play roles in the ecosystem that even we cannot see.”

And Jeff Wilser says the top seven man rules are:

- Tip well;

- You only recognize primary colors;

- Know how to give a compliment;

- Never say “blossom”;

- Keep an empty urinal between you and the next guy;

- Pack two pairs of shoes or fewer;

- and Outperform the GPS.

Male joking aside, the man’s role is in serious question—among men and women. The use of humor often highlights the fact that this topic is definitely on the docket in the American dialog.

The New Man Rules

A few things are clear. During this post-economic-meltdown era, certain things are in, like brown dress shoes, a little facial hair, leather bands on watches, v-neck sweaters, cuff links, and sneakers that are simple and cool.

“Women may not take note of the hours you log working out, but they will notice if you wear sneakers outside the gym,” one column assures us. The Prohibition-era look (recession, but not yet depression) and early sixties fashions are in — a rebellious comment against the Establishment.

But the serious advice to men is worth noting: “Optimal living isn’t about saving time. It’s about seizing control over the ways you spend it.” Get more done by getting out of bed as soon as you wake up, take real vacations to reboot, and “buy a trip, not a toy.”

Men are also told that “The New Rules for Men” include standing for something that matters, unplugging from electronics when it’s time to do important things, customizing many of the things you buy in life to fit your real needs and wants, and accepting that you can’t control everything.

“Standing for something” was the title of a book by Gordon B. Hinckley promoting, among other things, being a real man by being a truly good person, husband and father.

The “ideal of unplugging” was taught in the seventies by John Naisbitt in the bestselling Megatrends; he called it “High Tech, High Touch.”

“Customizing” was predicted in the 1990s as a major growing trend in our times by business guru Harry S. Dent, and the promotion of “accepting that which we cannot change” (and taking positive action to change those things we can and should) are as old as the Cicero, Cato, Aurelius and the Stoics. But bringing them all together for our time in history is, I think, quite profound.

It seems that while some women commentators are noting the popular ascendance of women and relative decline of man’s power, others are quick to point out that the equality of women is still a major unfulfilled challenge for feminism.

And where some men are ignoring or brushing off the trend with humor, at least one significant thing is happening among men: A lot of them are talking about what it means to be a man, how to be a real man, and what being a good man is all about. That’s not a revolution or a reform, it’s an internal renaissance among men.

This trend started (mainly among religious groups and authors) in the nineties, but it is taking on an increasingly mainstream tone.

For example, Philip Zimbardo of Stanford and John Boyd of Google teach in The Time Paradox that men who want to keep up with the coming future take more risks, remain goal-oriented, have strong impulse control, and take time to enjoy the present more often. Sounds almost Biblical. Or Shakespearean.

Boys 2 Men

Men are telling each other to be good. Somehow, in some way, the Great Recession moved a lot of men away from the playboy values of the roaring nineties toward more grown-up ideals.

Current advice to men includes: Eat better, drink more water, add fruits and vegetables to most of your meals, listen to more relaxing music, stop smoking, get more sleep, and so on.

This sort of advice has been served up for a long time, and there is a lot of the play-while-you’re-single commentary still, but some things have a newer ring: Work out more often in chores like “chopping and splitting wood,” “planting trees,” and “operating a floor sander,” eat more eggplant and also kale.

Also: Read more often in the deepest books, express more gratitude to your significant other, go out on more dates with her instead of just hanging out, give more service to your charity.

Make your own fate. In a political discussion, turn things to solutions instead of attacking sides. Spend less at restaurants and cook for her more often. Clear and clean the dishes.

Turn off all electronic devices at least 30 minutes before bed to increase the quality of your sleep. Be yourself, and better yourself.

Do wild things that make you feel like a man, and do them smart. Start a business. Increase your education. Take long hikes (customize and make your own trail mix).

“What a fairy-tale, romantic version of a man,” my 18-year-old daughter said when she read this. “Where did that list come from?”

When I told her it was mostly from one issue of Men’s Health, she was shocked. “That’s sooooo cool!” she exclaimed.

“I know, right?”

Be strong, innovative and reliable—these are some of the main messages men are now sending to men. And many women seem to agree. Where teen heart-throbs such as the unshaven young Leonardo DiCaprio used to be the choice for sexiest man alive, the top three right now are 47-year-old Johnny Depp, 42-year-old Hugh Jackman, and 36-year-old Christian Bale.

C.S. Lewis once wrote an article titled Men Without Chests to argue that we need more leaders who stand up for the good and against the bad, even when it is unpopular or difficult.

Decades later, The Weekly Standard published an article called “Men Without Chest Hair,” noting that then-teenager Leonardo DiCaprio had become the new male icon.

Today the grown-up, and very-non-teenage-looking, 36-year-old DiCaprio is still high on the list of “sexiest man alive.”

Teenage-looking men, like Zac Efron or Twilight’s Robert Pattinson, are rarely listed. Only five of them are in the top fifty, and even most of these look like they’re trying to appear older.

The most popular drama on television, according to Emmy voters, is Mad Men, which features middle-age men as its “handsome” leads. A headline in the woman’s magazine Glamour reads: “From silly boys…to ‘mad men.’”

Manhood 2050

I don’t know if the age of man is over or not, but the world can only benefit if more men work to become better. Not as a government program, mind you, but as a self-led-personal-improvement stimulus.

As corporate keynote speaker Bill Perkins suggested, there are times when real men need to break each of these six rules:

- Never get in a fight;

- Never risk it all;

- Never give up;

- Never ask for help;

- Never lose your cool;

- Never look stupid.

There are things worth fighting for, times to take more risk, habits and behaviors each of us should give up, times we really should ask for help, situations that require our full energy and passion, and experiences where humility and being willing to look stupid are exactly the right thing. Done correctly, all of these are characteristics of strength. There are many others.

I think maybe we’ve reached a point where the concern is a lot less about the differences between men and women than simply this: How can I be a better person?

Conclusion

We can wait for government, society, another institution, the experts, some great artist or something else to help us reconcile the male/female debate and bridge the gap between the various schools of thought on how men and women should be.

Or, finally, we can just get to work on truly improving ourselves. In this particular case, we all need to say “I” a lot more than “we.”

- I am improving the way I spend my evenings

- I am reading more things that matter

- I am spending more truly quality time with my kids

- I am doing more just because it is fun

- I am eating better

- I am taking long walks with my grandchildren

- I am making my work a real mission to improve the world

- I am smiling, laughing and relaxing a lot more

- I am finding so many fun ways of serving my wife

- I am helping build things that really make a positive difference

- I am working hard to…

- I am changing the way I used to…

- I am serving others in such great ways by…

- I am improving myself so much by…

- I am loving my new focus on…

- I am…

Regardless of the experts, what each of us does in our personal life is the key to the future. (And are there really any true experts on being a real man, husband and father—except, perhaps, great men, husbands and fathers—and, of course, your wife.)

There are so many things we can do, as men, right now to become better and to improve the world. We can do so much that is fun, that requires strength, that makes us feel truly alive. We can add so much meaning to the world.

Whatever the experts say, I believe we are living in the beginning of a renaissance of manhood. If not, it is time to start one.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Community &Culture &Current Events &Family &Featured &Generations &Mission

The Education Crossroads

November 12th, 2010 // 5:18 am @ Oliver DeMille

Education today is at a crossroads, and the options are fascinating.

Certainly the rise of the Internet has revolutionized most industries, and its impact on education is expected to be significant. But the change in technology isn’t the only major shift which is impacting schooling.

The end of the Cold War ushered in a new era of world politics — and of course, politics always impacts education.

Also, economic struggles have caused nations to put a premium on expenses, with the result that education is being asked to meet higher standards in order to justify its cost.

All of this would seem to indicate the need for broader, more inclusive and expansive education, with a focus on quality teaching and increased excellence.

Instead, these three trends have combined to create a surprising result.

Where increased Internet connections at first promised to bring more understanding, tolerance and cooperation between groups, the opposite has too often occurred.

Though we have the world at our online fingertips and the ability to interact directly with those of differing views, ideas and values, too many people are joining cliques that promote a narrow mindset and exclude and mistrust all others. The defensive posture occasioned by economic challenges and world events seems to increase this tendency.

Where is the Melting Pot?

The 18th and 19th century ideal of a melting pot doesn’t seem to be spreading enough online. In the 1970s it sort of evolved into the salad bowl idea, where differences were welcome as we all mixed together in a single serving.

Now we’re lucky if the clans in society agree to occupy a separate station at the same smorgasbord.

The danger to freedom is significant, maybe even extreme. James Madison taught in Federalist 10 that numerous factions would benefit freedom by keeping any one or two groups from becoming too powerful.

All decent groups would have a say in the world in this model, Madison argued. This benefit still remains in the Internet era.

But Madison also argued that people would come together when great cooperation was needed, that people and groups would put aside differences and collaborate on the important things.

Unfortunately, this powerful cultural model is unraveling in our time.

The reason is simple: As people increase their connections with those who agree with them on most things, they begin to fall into groupthink, a malady where most of those you communicate with agree with you on most things and disagree with you on little. Each member of the group learns how to more effectively argue the clique’s talking points, and nearly everyone stops listening to other points of view.

From Madison’s day until the Internet age, such natural bonding with groups was always tempered by geography. No matter how hard people tried to interact only with like thinkers, no matter how hard they worked to keep their children free from diverse views, neighbors nearly always ruined this utopian scheme.

The debate, the discussion, the conversations amongst diverse peoples all living in a free society — these helped individual citizens become deep thinkers and wise voters, and it helped ensure that negative traditions slowly were replaced with better ones. Without such progress, no free society can retain its freedoms.

But in the virtual age, no such checks or balances are in place. Youth and adults in all educational models and work environments are able to avoid deep conversations about important topics like politics, beliefs and principles with all who disagree with them.

This is facilitating a clique mentality. Social networks, email, cell phones and the other emerging technologies all strengthen this trend away from diverse and connected communities and toward homogenous and exclusive cliques.

The problem is that such cliques are by their very nature arrogant, overly sure of their own correctness on nearly everything, and vocally and even angrily opposed to pretty much everyone outside of their own clique.

Unfortunately, they too often spend a great deal of energy and effort demeaning other people, groups and ideas. Such cliques typically refuse to admit their own weaknesses while they label and vilify “outsiders.”

On the positive side, this is one reason there are now more independents than either Democrats or Republicans: a lot of people just got tired of too much hyper-partisan rhetoric.

But this problem goes far beyond politics, and impacts nearly every segment of our society. It is like adopting Elementary or High School culture among the adults in our world.

Dangerous Cliques

Since education is always an outgrowth of society, this trend is a major concern. The rebirth of tribes in our time, many of them online tribes made up of people who find common ground and like to work together, is the positive side of this same trend.

Indeed, using technology to interact and connect with people you like and learn with is certainly constructive. Leaders are needed to help increase the positive melting pot on line and in social networks.

Hopefully this will continue to grow. But its negative counterfeit is an increasing problem.

A first step in dealing with the growing “High School-ization” of our adult society is to simply identify the difference between the positive New Tribes and the opposing trend of growing cliques:

| New Tribes | Cliques |

| Tolerant, Inclusive, Friendly | Intolerant, Arrogant, Exclusive |

| Respectful of Other Views | Angry and Overly Critical of Other Views |

| Market by Helping You Find the Best Fit for You, From Them or Their Competitors | Market by Tearing Down Competitors to Build Themselves |

| Respect Your Ability to Make the Best Choices for You | Act As If You Need Their Expertise to Succeed and Will Fail Without Them |

| Offer to Help You Meet Your Needs | Try to Convince or Sell You to Act “Now” in the Way They Want, or You’ll Fail |

In short, the positive New Tribes offer you more freedom, empower you, and give you opportunities and options in a respectful and abundant way, while the clique mentality thinks it must “sell” you, convince you, and tear down the competition.

The New Tribes are relaxed, supportive and open, while cliques are closed, scarcity-minded and disrespectful of the competition and all “others.”

Ruining the Game

When my son was young he wanted to join a sports team, so I took him to watch a number of sports in progress. He ended up engaging karate, which became a long-term interest in his life.

During the visits to various sports venues, he witnessed an angry father at a little league baseball game. While most of the parents in attendance probably hoped their child would win, they seemed to find value in the game regardless of wins and losses; they apparently felt that the game was a positive experience for all the kids — for other children as well as their own.

One man took a different approach. He yelled and swore at each umpires’ calls that went against his child. He quite vocally demonized the other team and the other team’s coach. He stood behind the backstop when the other team was pitching and tried in many ways to distract the opposing pitcher.

He went after this 10-year-old pitcher from the other team like he actually wanted to hurt him. The boy’s coach had to go reassure the pitcher several times. I don’t know if the boy was afraid of the angry man, but he looked like it.

Most of the parents in the crowd were upset with this man, but they remained polite. After about 30 minutes of this, my eight-year-old son asked if we could leave. He was uncomfortable with the situation even as a mere spectator.

He never asked to go back to a baseball game, and we didn’t stay long enough to see if anything was done to help this man calm down. From the conversations in the crowd, it was clear that the man did this at every game.

I do believe that this man cared for his son and wanted to help him. He may have had many good intentions, and he certainly had some positive intentions. But he acted in the clique mentality. He did it without respect or proper boundaries.

(A new thought: I’m pretty sure he soured my son to playing baseball, but only now as I write this does it occur to me that maybe he also helped interest my son in karate for his own defense!)

A High-School-ization of Society

If you are this kind of a sports parent (or sports fan in high school, college or professional sports), you know who you are.

But do we not also see these clique behaviors too often in business, work, politics and even education?

Clearly the impact on education is significant. More to the point, the future of education can’t avoid being impacted by the High School-ization of culture.

Cliques are negative in many ways. And: they are just plain mean. They can do lasting damage even among youth; so imagine their potential impact when adopted by a significant and increasing number of adults of our society.

In short: the Cold War is over and we tend to look for enemies within rather than outside of our own nation; economic struggles of the past years have made most people less tolerant and more self-centered and even scared; and the technology of the day has made it easier than ever to connect with and only listen to a few people who tend to agree with us on almost everything.

The result is more frustration, anxiety, and anger with others. More people are thinking in terms of “us versus them,” and most of our society has stopped really listening to others.

Unless these tendencies change, things will only get worse. The future of education is closely connected with these trends, tendencies and perspectives.

In politics, the response to these challenges has been the rise of the independents. In business, it has been a growing rebirth of entrepreneurship.

And in marketing, it has been a focus on Tribes as the new key to sales. But in education, no clear solutions have yet arisen. I propose the principles of Leadership Education as part of the answer.

Modern versus Shakespearean Mindsets

The great classical writer Virgil provides some insight into the challenge ahead for education. In our day we tend to see the world as prose versus poetry. Some might call this same split the left brain versus the right brain, science versus art, or logic versus creativity.

Using this modern view of things, some educational thinkers see the future of education as the continuing split between the test-oriented public and traditional private schools versus the eclectic personalization of charter, the new private and home schooling movements.

Or we may see the intermixing of these two models as traditional schools become more creative and new-fangled education becomes more test-focused.

In an earlier age, the Shakespearean world tended to divide learning into three categories: comedies, tragedies and satires.

Comedies show regular people working in regular circumstances and finding love or happiness in regular life.

Tragedies pit people against drastic challenges that test them beyond their limits and bring major changes to their lives and even the world.

Satires emphasize the futility of our actions and show us the power of fate, destiny and other things we supposedly cannot control.

Applying this mindset, one would expect to see a future of education with all three outcomes. Comedic approaches to education try to make sure everyone gets basic literacy and that all schools meet minimum standards. No child can be left behind in this education for the regular people — and we’re all regular people.

In contrast, some will seek for a truly great education and to make a great difference in the world. If they fail, the tragedy is the loss of their potential greatness to the world. If they succeed, the world will greatly benefit from their leadership, contributions and examples.

All education should be great, this view maintains, and all people have potential greatness within. If I thought the Shakespearean worldview was driving our future, I would be of this view.

A satirical stance would argue that some people will get a poor education and yet do great things in their careers and family. Others, according to this view, will get a superb education and then either fail to accomplish much of anything or do many bad things with their knowledge.

Education has little correlation with life, the satirist maintains. Fund education better, or don’t; increase standards, or not; emphasize learning or just ignore it—none of this matters much in the satirical view. A few will rise, a few will fall, most will stay in the middle, and education will have little to do with any of this.

I disagree with this perspective, and I believe that history is proof of its inaccuracy. There are, of course, a few exceptions to any system, model or rule; but for the most part a quality educational model has a huge impact on the freedom and prosperity of society.

But I do not believe that either the modern or the Shakespearean mindsets will influence our future as much as that from and even earlier age — the era of Virgil.

But I do not believe that either the modern or the Shakespearean mindsets will influence our future as much as that from and even earlier age — the era of Virgil.

I am convinced that Virgil’s understanding of freedom eclipses both of these others. Virgil witnessed Rome losing many of its freedoms, and he saw how the educational system had a direct impact on this loss.

In the Virgilian model, education is not modeled on the conflict between left and right brains nor on the battles and interplay between comedy, tragedy and satire.

Instead, he saw learning as the interactions of the epic, the dialectic, the dramatic, and the lyric.

In our post-Cold-War, Internet-Age, financially challenging world, our learning is deeply connected with all four of these.

Epic education means learning from the great(est) stories of humanity in all fields of human history and endeavor, from the arts and sciences to government and history to leadership and entrepreneurship to family and relationships, and on and on.

By seeing how the great men and women of humanity chose, struggled, succeeded and failed, we gain a superb epic education. We learn what really matters.

The epics include all the greats — from the great scriptures of world religions to the great classics of philosophy, history, mathematics, art, music, etc.

Epic education focuses on the great classic works of mankind from all cultures and in all fields of learning.

Dialectic education uses the dialogues of mankind, the greatest and most important conversations of history and modern times. This includes biographies, original writings and documents that have made the most difference in the world. It is also very practical and includes on-the-job style learning.

Again, this tradition of learning pulls from all cultures and all fields of knowledge.

It especially focuses on areas (from wars and negotiations to courts of law and disputing scientists, to arguing preachers and the work of artists, etc.) where debating sides and conflicting opponents gave rise to a newly synthesized outcome and taught humanity more than any one side could have without opposition. Most of the professions use the Dialectic learning method.

Dramatic learning is that which we watch. This includes anything we experience in dramatic form, from cinema and movies to television and YouTube to plays, reality TV programs, etc.

In our day this has many venues—unlike the one or two dramatic forms of learning available in Virgil’s time. There is a great deal to learn from drama in its many classic, modern and post-modern modalities.

Lyric education is that which is accompanied by music, which has a significant impact on the depth and quality of how we learn. It was originally named for the Lyre, a musical instrument that was used for musical accompaniment during a play, or with poetic or prose reading.

Some educational systems still use “classical” (especially Baroque) and other types of music to increase student learning of languages, memorized facts and even science and math.

And, of course, most Dramatic (media) learning is presented with music.

Epic Freedom

With all this as background, I think the future of education is very much in debate. My reasons for addressing this are:

- It appears that far too few people are engaged in the current discussion that will determine the future of education.

- Even most who are part of the discussion are hung up on things like public versus private schools, funding, testing, left versus right brain, minimum standards for all (comedic) versus the offer of great education for most (to avoid tragedy), teacher training, regulations, policy, elections, etc.

- I know of very few people considering the future of education from its deepest (what I’m calling Virgil’s) level.

Specifically, our current technology has changed nearly everything regarding education, meaning that in the Internet Age the cultural impact of the Dramatic and Lyric styles of learning over the other types threaten to undo American freedom.

In short, freedom in any society depends on the education of the citizens, and when the Epic and Dialectic disappear, freedom soon follows.

And make no mistake: The Epic and Dialectic models of learning are everywhere under attack. They are attacked by the political Left as elitist and contrary to social justice; they are attacked by the political Right as useless for one’s career advancement.

They are attacked by the techies as old, outdated and at best quaint. They are attacked by the professions as “worthless general ed. courses,” and by too many educational institutions as “irrelevant to getting a job.”

But most of all (and this is far and away their most lethal enemy) they are supplanted by the simple popularity and glitz of the Dramatic and Lyric.

I do not believe that the Dramatic, Lyric and other parts of the entertainment industry have an explicit agenda to hurt education or freedom—far from it. They bask in a free economy that buys their products and glorifies their presenters.

Nor are Dramatic and Lyric products void of educational content or even excellence. Many movies, television programs, musical offerings and online sites deliver fabulous educational value.

Songs and movies, in fact, teach some of the most important lessons in our society and many teach them with elegance, quality and integrity.

But with all the good the Dramatic and Lyric styles of learning bring to society, the reality is that both free and enslaved societies in history have had Dramatic and Lyric learning.

In contrast, no society where the populace is sparsely educated in the Epics has ever remained free. Period. No exceptions.

And in the freest nations of history (e.g. Golden Age Greece, the Golden Age of the Roman Republic, the height of Ancient Israel, the Saracens, the Swiss vales, the Anglo-Saxon and Frank golden ages, and the first two centuries of the United States, among others), both the Epic and Dialectic styles of learning have been deep and widespread among the citizenship of the nation.

If we want to remain a free society, we must resurrect the use of Epic education in our nation.

Six Futures

Using Virgil’s models of learning as a standard, I am convinced that we are now choosing between six possible futures for our societal education—and freedom. Our choice, at the deepest level of education, is to select one of the six following options (or something very much like them):

I. Epic Only.

Since all societies adopt Dramatic and Lyric methods of learning, this model would make Epic education official in academic institutions and leave the Dramatic and Lyric teaching to the artists. Such a model is highly unlikely in a world where career seriously matters and has only been applied historically in slave cultures with strong upper classes.

(Theoretically, this model might be offered to all citizens in society instead of the more elitist model of history. But without career preparation, some in the lower and middle classes would be lacking in opportunity regardless of the quality of their Epic education.) This model is very bad for prosperity and freedom.

II. Dialectic Only.

Again, such a society would have non-school Dramatic and Lyric offerings and schools would emphasize career training, job preparation, and basic skills for one’s professional path.

Business, leadership and politics would be run by trained experts and citizens would have little say in governance. Like the aristocracies of history, this model is not friendly to freedom — though it can support prosperity for a short time.

III. Dramatic and Lyric Only.

Only tribal societies have adopted such a model, and they were easily conquered by enemies and marauders. This model is not good for prosperity or freedom.

IV. Epic and Dialectic Together.