The Little Fix

May 4th, 2011 // 2:45 pm @ Oliver DeMille

Sometimes small and simple things make all the difference. Malcolm Gladwell called this “the tipping point,” and an old proverb speaks of mere straws “breaking the camel’s back.” In my book FreedomShift I wrote about how three little things could—and should—change everything in America’s future.

Following is a little quote that holds the fix to America’s modern problems. This is a big statement. Many Americans feel that the United States is in decline, that we are facing serious problems and that Washington doesn’t seem capable of taking us in the right direction. People are worried and skeptical. Washington—whichever party is in power—makes promises and then fails to fulfill them.

What should America do? The answer is provided, at least the broad details, in the following quote. The famous Roman thinker Cicero is said to have given us this quote in 55 BC. However, it turns out that this quote was created in 1986 as a newspaper fabrication.[i] Still, the content of the quote carries a lot of truth:

“The budget should be balanced, the Treasury should be refilled, public debt should be reduced, the arrogance of officialdom should be tempered and controlled, and the assistance to foreign lands should be curtailed lest Rome become bankrupt.”

Consider each item:

- Balance the budget. There are various proposals to do this, nearly all of which require cutting entitlements and also foreign military expenditures. Many do not require raised tax rates. But most Americans would support moderate tax increases if Washington truly gets its outrageous spending habit under control. Paying more taxes in order to see our national debts paid off and our budgets balanced would be worth it—if, and only if, we first witness Washington really fix its spending problem.

- Refill the Treasury. This is seldom suggested in modern Washington. We have become so accustomed to debt, it seems, that the thought of maintaining a long-term surplus in Washington’s accounts is hardly ever mentioned.

- Reduce public debt. This is part of various proposals, and is a major goal of many American voters (including independents, who determine presidential elections).

- Temper and control the arrogance of officialdom. This is seldom discussed, but it is a significant reality in modern America. We have become a society easily swayed by celebrity, and this is bad for freedom.

- Curtail foreign aid. The official line is that the experts, those who “understand these things,” know why we must continue and even expand foreign aid, and that those who oppose this are uneducated and don’t understand the realities of the situation. The reality, however, is that the citizenry does understand that we can’t spend more than we have. Period. The experts would do well to figure this out.

The question boils down to this: Is the future of America a future of freedom or a future of big government? Our generation must choose.

The challenge so far is that the American voter wants less expensive government but also big-spending government programs. Specifically, we want government to stop spending for programs which benefit other people, but to keep spending for programs that benefit us directly.[ii] We want taxes left the same or decreased for us, but raised on others. We want small business to create more jobs, but we want small businesspeople to pay higher taxes (we don’t want to admit that by paying higher taxes they’ll naturally need to reduce the number of jobs they offer).

The modern American citizen wants the government programs “Rome” can offer, but we want someone else to pay for it. We elect leaders who promise smaller government, and then vote against them when they threaten a government program we enjoy.

Over time, however, we are realizing that we can’t have it both ways. We are coming to grips with the reality that to get our nation back on track we’ll need to allow real cuts that hurt. The future of America depends on how well we stick to our growing understanding that our government must live within its means.

[i] Discussed in Gary Shapiro, The Comeback: How Innovation Will Restore The American Dream.

[ii] See Meet the Press, April 24, 2011.

**********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Blog &Citizenship &Culture &Economics &Education &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History

The Clash of Two Cultures

April 26th, 2011 // 8:30 am @ Oliver DeMille

America is in the midst of a major clash of two cultures. Most of the rich world, and the developing world as well, are experiencing the same challenge.

This contest is seldom cooperative, often violent, and increasingly heated. It has the passion of the age-old class debate between the rich and the middle classes, the political angst of Republican versus Democrat, or the intensity of Cold War America versus the Soviet Union. It is much more obsessive than raging sports rivalries which so many Americans have experienced.

This conflict is intellectual in nature, though its results are physical, economic and substantive. There have been such intellectual battles before, such as conservatism versus liberalism. But, given human nature, the conservative-progressive debate seldom gained the zeal or ardor of Democratic fights with Republicans. Somehow having professionals who make their living promoting each opposing side drastically intensifies the natural belligerence of skirmishing viewpoints. In fact, it has been intellectual wars that caused the greatest conflicts of history—from strife between religions to capitalism versus communism.

The sides of this new war are conformity and innovation. This may at first sound less hostile than some struggles, but it would be a mistake to underestimate this issue. It is remaking the world as we know it.

Of course, those who support conformity have been around for a long time. And innovation has always been a rowdy, if lucrative, minority movement. Ironically, the leaders of conformity have typically come from the upper classes—nearly all of whose wealth, family legacy, and status was created by one or more ancestral innovator(s). Innovation breeds growth, wealth, success and status. The old parable of the tree house, as told to me by a partner of a major Los Angeles law firm, is applicable: build the tree house, then kick out the ladder so only those you personally select can ever come up.

Of course, the extreme of either side is—as extremes tend to be—worse than the moderate of either. Pure innovation with no regard for the lessons of history is just as bad as dogmatic conformity without openness, toleration or creativity. When I speak here of Innovation I mean a bent toward innovation within the proven rules of happiness and wisdom, and by Conformity I mean a focus on fitting in but with some open-mindedness in times of challenge. Note that even these two moderate styles are almost polar opposites.

Nearly all of our schools have a hidden, compulsory curriculum of training for conformity, and innovative teachers or institutions are pressured to become like the rest or face widespread official rebuke. The classic movie Dead Poet’s Society portrays this well.

Our universities follow this pattern more often than not, as do most institutions in our society. Entrepreneurship, for example, which is the catalyst of nearly all great business growth, is considered “lesser” by most business students and MBA programs. Many great companies were founded and built by individuals whose resumes would not get past the first glance in personnel departments of those same corporations today. And, indeed, the company’s biggest competitors are likely to be led by innovative thinkers and leaders who likewise wouldn’t get a job at the company (too many Ivy League MBA’s to compete with).

A quick read of the bestselling Rich Dad, Poor Dad shows how these two mindsets sometimes present themselves in families. But these two cultures are found at all social levels and in every geographical setting. Blue-collar working fathers are as likely to spout conforming rules as silver-spoon fathers: “This is just how things are; so you better get used to it!” “But, dad…” “Don’t contradict me. The world is what the world is! I’m telling you how things are!”

Such rigid thinking is a symptom of the widespread doctrine of conformity. It rules in many families, communities, businesses, schools, churches, nations, associations—indeed, almost everywhere. It is, in fact, on the throne in nearly every setting and society. It has the benefit of learning from the best lessons of the past, but it seems to chronically ignore the lesson that innovation is both advantageous and desired.

Futurist Alvin Toffler argued that our schools will not be competitive in the world economy unless we replace rote memorization, fitting in, and getting the “right” answer with things like independent thinking, leadership practice, creativity and entrepreneurialism. Several of Harvard’s educational scholars and Secretary of Education Arne Duncan have made the same point—repeatedly.

But our schools are run on conformity, and until we promote innovators to educational leadership such changes will be rare. And when we do put innovators in charge, the attacks from entrenched powers are incessant.

Likewise, our economic experts are those who conform to the “accepted” analyses—economists with divergent, and often more accurate, predictions based on innovative models are given little press by the conformist economics, academic and media professions.

I have long suggested that the way to fix American education is to get truly great teachers in more of our classrooms. But innovative teachers often don’t fit in the bureaucratic school systems. Many of the best teachers leave schools simply because they can’t innovate in a conformist system.

An article by Tim Kane in The Atlantic noted:

“Why are so many of the most talented officers now abandoning military life for the private sector? An exclusive survey of West Point graduates shows that it’s not just money. Increasingly, the military is creating a command structure that rewards conformism and ignores merit. As a result, it’s losing its vaunted ability to cultivate entrepreneurs in uniform.”

This seems indicative of our entire culture right now. Conformity is winning far too often. Companies and organizations which elect to encourage the innovative side of the debate are seeing huge success, but this is taking many of the “best and brightest” away from academia, the public sector and the United States to more entrepreneurial-minded environments in private companies and international firms.

In far too many cases, we kill the human spirit with rules of bureaucratic conformity and then lament the lack of creativity, innovation, initiative and growth. We are angry with companies that take their jobs abroad, but refuse to become the kind of employees that would guarantee their stay. We beg our political leaders to fix things, but don’t take initiative to build entrepreneurial solutions that are profitable and impactful.

The future belongs to those who buck these trends. These are the innovators, the entrepreneurs, the creators, what Chris Brady has called the Rascals. We need more of them. Of course, not every innovation works and not every entrepreneur succeeds, but without more of them our society will surely decline. Listening to some politicians in Washington, from both parties, it would appear we are on the verge of a new era of conformity! “Better regulations will fix everything,” they affirm.

The opposite is true. Unless we create and embrace a new era of innovation, we will watch American power decline along with numbers of people employed and the prosperity of our middle and lower classes. So next time your son, daughter, employee or colleague comes to you with an exciting idea or innovation, bite your tongue before you snap them back to conformity.

The future of our freedom and prosperity depends on innovative thinking, and the innovation we need may be in the mind of your fifteen-year-old son or your husband, wife or employee. This battle will ultimately be fought in families, where youth get their fundamental cultural leaning—toward either conformity, seeking popularity and impressing others or, in contrast, creativity, initiative, and innovation.

Thomas Jefferson Education is naturally pointed toward innovation, but it is up to parents, mentors and teachers to implement this leadership skill. I invite all to join this battle, and to join it firmly committed to the side of innovation. Do whatever you can to encourage innovation and be skeptical of rote conformity. That’s a change that could literally change everything.

**********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Blog &Business &Culture &Education &Family &Government &Independents &Leadership

The Freud Doctrine

April 21st, 2011 // 7:35 am @ Oliver DeMille

Freud has too much power in our current world. Those who practice in the mental health fields know that little of Freud is still used in modern psychology; and most others only read Freud, if at all, from a few selected readings in a basic psychology course from college. But Freud’s lasting legacy comes from another source—one that has significantly influenced our modern world in ways little understood.

Freud’s view of reality and truth dominates much of the modern world, even among people who have never closely read or studied his writings. One glaring example can be found in Freud’s teachings about science.

He wrote that science:

“…asserts that there is no other source of knowledge of the universe, but the intellectual manipulation of carefully verified observations, in fact, what is called research, and that no knowledge can be obtained from revelation, intuition, or inspiration.

“It is inadmissible to declare, that science is one field of human intellectual activity, and that religion and philosophy are others, at least as valuable, and that science has no ability to interfere with the other two, that they all have an equal claim to truth, and that everyone is free to choose whence he shall draw his conviction and in which he shall place his belief.

“Such an attitude is considered particularly respectable, tolerant, broad-minded, and free from narrow prejudices. Unfortunately, it is not tenable…. The bare fact is that truth cannot be tolerant and cannot admit compromise or limitations, that scientific research looks on the whole field of human activity as its own, and must adopt an uncompromisingly critical attitude towards any other power that seeks to usurp any part of its province.”

In short: In the Freudian worldview, science is the only source of truth for any and all fields of knowledge, and it must take “an uncompromisingly critical attitude” toward any other source of knowledge. We might call this The Freud Doctrine.

The debates between “science” and “religion” are well known. In fairness, religion has often taken half of the same stance—that God’s wisdom applies to all areas of knowledge—and at times even the second half of the model—that religion should therefore have a critical attitude toward science and other sources of knowledge. Indeed, the injustices heaped upon Copernicus and Galileo, among others, are clear examples of church overreach into the works of science.

But it is Freud’s argument that science is above philosophy that has perhaps had the most negative impact on modern politics and society. Science gets its knowledge through experimentation, and it has become a field dominated by experts and specialists. Most religions claim knowledge through revealed writings, and they are also nearly all subject to the authority of official leaders. Indeed, the professionals of science and religion have long battled each other in many arenas.

In contrast, philosophy, as much as it had accepted leaders in ancient times, is now wide open to the masses. Freud’s attack on philosophy therefore amounts in our day to a decree that the common sense of the regular citizen and the reason of the average person must be overseen by the “true” and “accepted” wisdom of the experts—who, of course, base their conclusions on research, scientific methodology and therefore “real truth” rather than the “inferior thinking of the common man.”

Whether Freud meant by “philosophy” the work of philosophy professionals in the academy or the daily reason of the people is irrelevant; in our time a literal elite class of professionals, experts and officials apply his teaching like a prime directive—without questioning assumptions and with immediate rancor for any who question the dogma of the primacy of scientific research. “The Freud Doctrine” is a reality in our world.

There are a number of problems with The Freud Doctrine, the idea that only the professionals and experts understand the truth because only they rely entirely on credible research, and that the rational thought of non-experts and the non-credentialed (and even those with prestigious credentials whose conclusions are outside the expert consensus) is simply inferior.

First, this idea isn’t even internally consistent. For example, the accepted experts in this model systemically disagree with each other—the top experts in the social sciences, hard sciences and mathematical fields often come up with widely divergent conclusions as they attempt to deal with a given problem. At a deeper level, few mathematical schools of thought agree on many of the basics, and the gaps in agreement between biologists, chemists and physicists are legendary. Add the practical fields like medicine and engineering, and the conflicts are epic. How can we truly trust the experts when so many of them disagree on so much?

Second, on a logical level, the Freudian-based worldview isn’t even tenable. For example, Freud’s insistence that only experimental knowledge has any basis of truth, that everything else is “not tenable” and must be resisted in “intolerant” and “uncompromising” ways, leaves out at least two important fields of knowledge that are highly credible in the modern perspective: mathematics and logic. Put simply, neither mathematics nor logic is experimental. In fact, all the major arguments against using religion or reason to find truth also discredit the validity of logic and math. Yet the modern faith in experts includes mathematics and formal logic along with the hard sciences.

Third, and this is the most significant problem with the modern system of leaving our leadership to the experts, this approach hasn’t worked very well. As David Brooks wrote in The Social Animal:

“Since 1983 we’ve reformed the education system again and again, yet more than a quarter of high-school students drop out, even though all rational incentives tell them not to. We’ve tried to close the gap between white and black achievement, but have failed. We’ve spent a generation enrolling more young people in college without understanding why so many don’t graduate.

“One could go on: We’ve tried feebly to reduce widening inequality. We’ve tried to boost economic mobility. We’ve tried to stem the tide of children raised in single-parent homes. We’ve tried to reduce the polarization that marks our politics. We’ve tried to ameliorate the boom-and-bust cycle of our economics. In recent decades, the world has tried to export capitalism to Russia, plant democracy in the Middle East, and boost development in Africa. And the results of these efforts are mostly disappointing.

“The failures have been marked by a single feature: Reliance on an overly simplistic view of human nature. Many of these policies were based on the shallow social-science model of human behavior. Many of the policies were proposed by wonks who are comfortable only with traits and correlations that can be measured and quantified.”

There are many other examples. Legislatures have trusted experts, the citizenry has trusted experts and legislators, and the results have been less than exemplary. When policy is based on research and experimentation, common sense is sparsely applied and, it turns out, desperately needed.

This is not an indictment of science. Most scientists would observe the limp results of too much Ivory Towerism and alter their hypotheses and policies. The major problem with The Freud Doctrine as it has evolved to date is that our policies give full lip service to science, use the gravitas of “science” to shut down views from religion or art or worst of all common reason, and then ignore science as it becomes entirely politicized in our legislatures and especially in bureaucratic implementation and judicial oversight.

The tragedy is that the whole process flies above the active participation of the common citizen. After all, unless you are a professional scientist or researcher, Freud’s system has discredited anything you have to add. Professional politicians get around this by citing the experts, as do professional journalists. But the citizens—they are relegated to the gallery, where they are told to observe as long as they stay quiet and don’t disturb the process.

The Internet has changed all this, or at least it has started the change. The experts (predictably) complain that much of what is written online doesn’t meet rigorous scientific standards. Thank goodness for that! The shift is evoking the return of a long-underutilized human ability among the regular citizenry—listening to and learning truth from analytical reason. Lots of the online analysis is shallow, misleading or false, which causes readers to turn on their reason and really think things through. A new period of deep-thinking citizens is emerging.

The war between “truth by experts” and “truth from widespread individual reason” (Freud vs. Jefferson) has just begun, but the results seem inevitable. Barring a shut-down of open dialogue, the future of independent thinking and the freedom it usually engenders is bright.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Blog &Culture &Education &Generations &Government &Leadership &Postmodernism

Is America a Democracy, Republic, or Empire?

April 20th, 2011 // 7:09 am @ Oliver DeMille

Some in Washington are fond of saying that certain nations don’t know how to do democracy.

Anytime a nation breaks away from totalitarian or authoritarian controls, these “experts” point out that the people aren’t “prepared” for democracy.

But this is hardly the point.

A nation where the people aren’t prepared for democracy–but where a strong leader is prepared for tyranny–is still better off as a democracy.

A nation where the people aren’t prepared for democracy but where an elite class is prepared for aristocracy is still better off as a democracy.

A nation where the people aren’t prepared for democracy but where a socialist or fundamentalist religious bureaucracy is prepared to rule is still better off as a democracy.

Whatever the people’s inadequacies, they will do better than the other, class-dominant forms of government.

Winston Churchill was right:

“Democracy is the worst form of government–except for all those others that have been tried.”

False Democracy

When I say “democracy,” I am of course not referring to a pure democracy where the masses make every decision; this has always turned to mob rule through history.

Of Artistotle’s various types and styles of democracy, this was the worst. The American founders considered this one of the least effective of free forms of government.

Nor do I mean a “socialist democracy” as proposed by Karl Marx, where the people elect leaders who then exert power over the finances and personal lives of all citizens.

Whether this type of government is called democracy (e.g. Social Democrats in many former Eastern European nations) in the Marxian sense or a republic (e.g. The People’s Republic of China, The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics–USSR, etc.), it amounts to the same oligarchic model of authoritarian rule.

Marx used the concept of democracy–he called it “the battle for democracy”–to argue for the working classes to rise up against the middle and upper classes and take back their power.

Ironically, he believed the masses incapable of such leadership, and felt that a small group of elites, the “vanguard”, would have to do the work of the masses for them.

This argument assumes an oligarchic view of the world, and the result of attempted Marxism has nearly always been dictatorial or oligarchic authoritarianism.

In this attitude Marx follows his mentor Hegel, who discounted any belief in the power or wisdom of the people as wild imaginings (see Mortimer Adler’s discussion on “Monarchy” in the Syntopicon).

The American founders disagreed entirely with this view.

A Democratic Republic

The type of democracy we need more of in the world is constitutional representative democracy, with:

A written constitution that separates the legislative, executive and judicial powers. Limits all with checks and balances, and leaves most of the governing power in the hands of the people and local and regional, rather than national, government institutions.

In such a government, the people have the power to elect their own representatives who participate at all levels. Then the people closely oversee the acts of government.

One other power of the people in a constitutional representative democratic republic is to either ratify or reject the original constitution.

Only the support of the people allows any constitution to be adopted (or amended) by a democratic society.

The American framers adopted Locke’s view that the legislative power was closest to the people and should have the sole power over the nation’s finances.

Thus in the U.S. Constitution, direct representatives of the people oversaw the money and had to answer directly to the people every two years.

Two Meanings of “Democracy”

There are two ways of understanding the term democracy. One is as a governmental form–which is how this article has used the word so far. The other is as a societal format.

There are four major types of societies:

- A chaotic society with no rules, laws or government

- A monarchical society where one man or woman has full power over all people and aspects of the society

- An aristocratic society where a few people–an upper class–control the whole nation

- A democratic society where the final say over the biggest issues in the nation comes from the regular people

As a societal form, democracy is by far the best system.Montesquieu, who was the source most quoted at the American Constitutional Convention, said:

“[Democracy exists] when the body of the people is possessed of the supreme power.”

In a good constitutional democracy, the constitution limits the majority from impinging upon the inalienable rights of a minority–or of anyone at all.

Indeed, if a monarchical or aristocratic society better protects the rights of the people than a democratic nation, it may well be a more just and free society.

History has shown, however, that over time the people are more likely to protect their rights than any royal family or elite class.

When the many are asked to analyze and ratify a good constitution, and then to protect the rights of all, it turns out they nearly always protect freedom and just society better than the one or the few.

It is very important to clarify the difference between these two types of democracy–governmental and societal.

For example, many of the historic Greek “democracies” were governmental democracies only. They called themselves democracies because the citizens had the final say on the governmental structure and elections–but only the upper class could be citizens.

Thus these nations were actually societal aristocracies, despite being political democracies.

Plato called the societal form of democracy the best system and the governmental format of democracy the worst.

Clearly, knowing the difference is vital.

Aristotle felt that there are actually six major types of societal forms.

A king who obeys the laws leads a monarchical society, while a king who thinks he is above the law rules a tyrannical society.

Likewise, government by the few can either have different laws for the elite class or the same laws for all people, making oligarchy or aristocracy.

In a society where the people are in charge, they can either rule by majority power (he called this democracy) or by wise laws, protected inalienable rights and widespread freedom (he called this “mixed” or, as it is often translated, “constitutional” society).

Like Plato, Aristotle considered the governmental form of democracy bad, but better than oligarchy or tyranny; and he believed the societal form of democracy (where the people as a mass generally rule the society) to be good.

Democracy or Republic?

The authors of The Federalist Papers tried to avoid this confusion about the different meanings of “democracy” simply by shortening the idea of a limited, constitutional, representative democracy to the term “republic.”

A breakdown of these pieces is enlightening:

- Limited (unalienable rights for all are protected)

- Constitutional (ratified by the people; the three major powers separated, checked and balanced)

- Representative (the people elect their leaders, using different constituencies to elect different leaders for different governmental entities–like the Senate and the House)

- Democracy (the people have the final say through elections and through the power to amend the constitution)

The framers required all state governments to be this type of republic, and additionally, for the national government to be federal (made up of sovereign states with their own power, delegating only a few specific powers to the national government).

When we read the writings of most of the American founders, it is helpful to keep this definition of “republic” in mind.

When they use the terms “republic” or “a republic” they usually mean a limited, constitutional, representative democracy like that of all the states.

When they say “the republic” they usually refer to the national-level government, which they established as a limited, constitutional, federal, representative democracy.

At times they shorten this to “federal democratic republic” or simply democratic republic.

Alexander Hamilton and James Wilson frequently used the term “representative democracy,” but most of the other founders preferred the word “republic.”

A Global Problem

In today’s world the term “republic” has almost as many meanings as “democracy.”

The term “democracy” sometimes has the societal connotation of the people overseeing the ratification of their constitution. It nearly always carries the societal democracy idea that the regular people matter, and the governmental democracy meaning that the regular people get to elect their leaders.

The good news is that freedom is spreading. Authoritarianism, by whatever name, depends on top-down control of information, and in the age of the Internet this is disappearing everywhere.

More nations will be seeking freedom, and dictators, totalitarians and authoritarians everywhere are ruling on borrowed time.

People want freedom, and they want democracy–the societal type, where the people matter. All of this is positive and, frankly, wonderful.

The problem is that as more nations seek freedom, they are tending to equate democracy with either the European or Asian versions (parliamentary democracy or an aristocracy of wealth).

The European parliamentary democracies are certainly an improvement over the authoritarian states many nations are seeking to put behind them, but they are inferior to the American model.

The same is true of the Asian aristocratic democracies.

Specifically, the parliamentary model of democracy gives far too much power to the legislative branch of government, with few separations, checks or balances.

The result is that there are hardly any limits to the powers of such governments. They simply do whatever the parliament wants, making it an Aristotelian oligarchy.

The people get to vote for their government officials, but the government can do whatever it chooses–and it is run by an upper class.

This is democratic government, but aristocratic society. The regular people in such a society become increasingly dependent on government and widespread prosperity and freedom decrease over time.

The Asian model is even worse. The governmental forms of democracy are in place, but in practice the very wealthy choose who wins elections, what policies the legislature adopts, and how the executive implements government programs.

The basic problem is that while the world equates freedom with democracy, it also equates democracy with only one piece of historical democracy–popular elections.

Nations that adopt the European model of parliamentary democracy or the Asian system of aristocratic democracy do not become societal democracies at all–but simply democratic aristocracies.

Democracy is spreading–if by democracy we mean popular elections; but aristocracy is winning the day.

Freedom–a truly widespread freedom where the regular people in a society have great opportunity and prosperity is common–remains rare around the world.

The Unpopular American Model

The obvious solution is to adopt the American model of democracy, as defined by leading minds in the American founding: limited, constitutional, representative, federal, and democratic in the societal sense where the regular people really do run the nation.

Unfortunately, this model is currently discredited in global circles and among the world’s regular people for at least three reasons:

1. The American elite is pursuing other models.

The left-leaning elite (openly and vocally) idealize the European system, while the American elite on the right prefers the Asian structure of leadership by wealth and corporate status.

If most of the intelligentsia in the United States aren’t seeking to bolster the American constitutional model, nor the elite U.S. schools that attract foreign students on the leadership track, it is no surprise that freedom-seekers in other nations aren’t encouraged in this direction.

2. The American bureaucracy around the world isn’t promoting societal democracy but rather simple political democracy–popular elections have become the entire de facto meaning of the term “democracy” in most official usage.

With nobody pushing for limited, constitutional, federal, representative democratic republics, we get what we promote: democratic elections in fundamentally class-oriented structures dominated by elite upper classes.

3. The American people aren’t all that actively involved as democratic leaders.

When the U.S. Constitution was written, nearly every citizen in America was part of a Town Council, with a voice and a vote in local government. With much pain and sacrifice America evolved to a system where every adult can be such a citizen, regardless of class status, religious views, gender, race or disability.

Every adult now has the opportunity to have a real say in governance. Unfortunately, we have over time dispensed with the Town Councils of all Adults and turned to a representative model even at the most local community and neighborhood level.

As Americans have ceased to participate each week in council and decision-making with all adults, we have lost some of the training and passion for democratic involvement and become more reliant on experts, the press and political parties.

Voting has become the one great action of our democratic involvement, a significant decrease in responsibility since early America.

We still take part in juries–but now even that power has been significantly reduced–especially since 1896.

In recent times popular issues like environmentalism and the tea parties have brought a marked increase of active participation by regular citizens in the national dialogue.

Barack Obama’s populist appeal brought a lot of youth into the discussion. The Internet and social media have also given more power to the voice of the masses.

When the people do more than just vote, when they are involved in the on-going dialogue on major issues and policy proposals, the society is more democratic–in the American founding model–and the outlook for freedom and prosperity brightens.

The Role of the People

Human nature being what it is, no people of any nation may be truly prepared for democracy.

But–human nature being what it is–they are more prepared to protect themselves from losses of freedom and opportunity than any other group.

Anti-democratic forces have usually argued that we need the best leaders in society, and that experts, elites and those with “breeding,” experience and means are most suited to be the best leaders.

But free democratic societies (especially those with the benefits of limited, constitutional, representative, and locally participative systems) have proven that the right leaders are better than the best leaders.

We don’t need leaders (as citizens or elected officials) who seem the most charismatically appealing nearly so much as we need those who will effectively stand for the right things.

And no group is more likely to elect such leaders than the regular people.

It is the role of the people, in any society that wants to be or remain free and prosperous, to be the overseers of their government.

If they fail in this duty, for whatever reason, freedom and widespread prosperity will decrease. If the people don’t protect their freedoms and opportunities, despite what Marx thought, nobody will.

No vanguard, party or group of elites or experts will do as much for the people as they can do for themselves. History is clear on this reality.

We can trust the people, in America and in any other nation, to promote widespread freedom and prosperity better than anyone else.

Two Challenges

With that said, we face at least two major problems that threaten the strength of our democratic republic right now in the United States.

First, only a nation of citizen-readers can maintain real freedom. We must deeply understand details like these:

- The two meanings of democracy

- The realities and nuances of ideas such as: limited, constitutional, federal, representative, locally participative, etc.

- The differences between the typical European, Asian, early American and other models competing for support in the world

- …And so on

In short, we must study the great classics and histories to be the kind of citizen-leaders we should be.

The people are better than any other group to lead us, as discussed above, but as a people we can know more, understand more, and become better leaders.

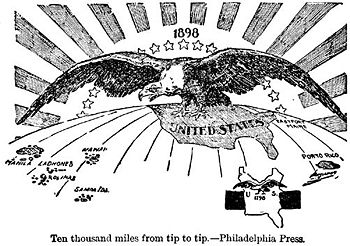

As George Friedman has argued, we now control a world empire larger than any in history, whether we want to or not.

Yet a spirit of democratic opportunity, entrepreneurial freedom, inclusive love of liberty, freedom from oppressive class systems, and promotion of widespread prosperity is diametrically opposed to the arrogant, selfish, self-elevating, superiority-complex of imperialism.

This very dichotomy has brought down some of the greatest free nations of history.

On some occasions this challenge turned the home nation into an empire, thus killing the free democratic republic (e.g. Rome).

Other nations lost their power in the world because the regular people of the nation did not reconcile their democratic beliefs with the cruelty of imperial dominance and force (e.g. Athens, ancient Israel).

At times the colonies of an empire used the powerful democratic ideals of the great power against them and broke away.

At times the citizens of the great power refused to support the government in quelling rebellions with which they basically agreed (e.g. Great Britain and its relations with America, India, and many other former colonies).

Many of the great freedom thinkers of history have argued against empire and for the type of democratic republic the American framers established–see for example Herodotus, Thucydides, Aristotle, the Bible, Plutarch, Tacitus, Augustine, Montaigne, Locke, Montesquieu, Gibbon, Jefferson, The Declaration of Independence, and Madison, among others.

The Federalist mentions empire or imperialism 53 times, and not one of the references is positive.

In contrast, the main purpose of the Federalist Papers was to make a case for a federal, democratic republic.

Those who believe in American exceptionalism (that the United States is an exception to many of the class-oriented patterns in the history of nations) now face their greatest challenge.

Will America peacefully and effectively pull back from imperialism and leave dozens of nations successfully (or haltingly) running themselves without U.S. power?

Will it set its best and brightest to figuring out how this can be done? Or to increasing the power of empire?

Empire and Freedom

Some argue that the United States cannot divest itself of empire without leaving the world in chaos.

This is precisely the argument nearly all upper classes, and slave owners, make to justify their unprincipled dominance over others.

The argument on its face is disrespectful to the people of the world.

Of course few people are truly prepared to run a democracy–leadership at all levels is challenging and at the national level it is downright overwhelming.

But, again–the people are more suited to oversee than any other group.

And without the freedom to fail, as Adam Smith put it, they never have the dynamic that impels great leaders to forge ahead against impossible odds. They will never fly unless the safety net is gone.

The people can survive and sometimes even flourish without elite rule, and the world can survive and flourish without American empire.

A wise transition is, of course, the sensible approach, but the arrogance of thinking that without our empire the world will collapse is downright selfish–unless one values stability above freedom.

How can we, whose freedom was purchased at the price of the lives, fortunes and sacred honor of our forebears, and defended by the blood of soldiers and patriots in the generations that followed, argue that the sacrifices and struggles that people around the world in our day might endure to achieve their own freedom and self- determination constitute too great a cost?

The shift will certainly bring major difficulties and problems, but freedom and self-government are worth it.

The struggles of a free people trying to establish effective institutions through trial, error, mistakes and problems are better than forced stability from Rome, Madrid, Beijing, or even London or Washington.

America can set the example, support the process, and help in significant ways–if we’ll simply get our own house in order.

Our military strength will not disappear if we remain involved in the world without imperial attitudes or behaviors. We can actively participate in world affairs without adopting either extreme of isolationism or imperialism.

Surely, if the world is as dependent on the U.S. as the imperial-minded claim, we should use our influence to pass on a legacy of ordered constitutional freedom and learning self-government over time rather than arrogant, elitist bureaucratic management backed by military might from afar.

If Washington becomes the imperial realm to the world, it will undoubtedly be the same to the American people. Freedom abroad and at home may literally be at stake.

The future will be significantly impacted by the answers to these two questions:

Will the American people resurrect a society of citizen readers actively involved in daily governance?

Will we choose our democratic values or our imperialistic attitudes as our primary guide for the 21st Century?

Who are we, really?

Today we are part democracy, part republic, and part empire.

Can we find a way to mesh all three, even though the first two are fundamentally opposed to the third?

Will the dawn of the 22nd Century witness an America free, prosperous, strong and open, or some other alternative?

If the United States chooses empire, can it possibly retain the best things about itself?

Without the Manifest Destiny proposed by the Founders, what alternate destiny awaits?

Above all, will the regular citizens–in American and elsewhere–be up to such leadership?

No elites will save us. It is up to the people.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Constitution &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History &Leadership &Liberty &Politics &Postmodernism &Statesmanship

Quantity. Quality. Method.

April 12th, 2011 // 6:45 am @ Oliver DeMille

How much?

How well?

How?

These three aspects of success in any endeavor can teach us a lot about government, freedom and prosperity. Most importantly, they can teach us about government for freedom—since most governments in history have had different goals than liberty.

Good government—which maintains freedom and opportunity for all citizens—must meet the tests of quantity, quality and method. We naturally use all three in governmental analysis, often without noticing it. For example, terms such as democracy, aristocracy and monarchy emphasize the quantity of leaders—many, few or one. In contrast, we emphasize the method of governance in terms like communist, capitalist, commercial, and limited governments—these all describe the process which drives their respective societies. Words such as oligarchy, confederation, socialist, mercantile, militarist, federal, national and empire deal with the qualities of a nation’s governance, the attributes that make it what it is.

Quality, quantity and method are different ways to analyze any governmental institution, power, program or proposal. All three are important. Before we tackle how this applies to government, let’s learn a little about these three perspectives using a few examples. In the Great Books, for example, the discussion of quality centers on primary versus secondary qualities: attributes that cannot be separated from a thing are primary qualities, while attributes that can be changed without changing the thing—like color, taste, number or temperature, etc.—are secondary.

As for quantity, a big debate through written history has been the question of why mathematics doesn’t directly apply to the real world. Engineers, inventors and others who use math in the real world have to calculate for various non-mathematical realities in order to apply math to real things. This has caused many arguments among the great thinkers, from Aristotle to Buckminster Fuller. Newton invented calculus in order to bridge the gap between the mathematical and physical universes.

Perhaps the most interesting point about all this is that the discussion of method, as opposed to quality and quantity, runs through the Great Books and great conversation of history at nearly every turn. Almost every topic covered by the great thinkers and leaders from ancient, medieval and early modern (1800s) times deals extensively with competing ideas of method. Amazingly, this significantly slows in modern times, especially after 1900. Somehow the general acceptance of scientific experts as the true authorities on almost everything caused, or at least coincided with, a reduction of the common people asking questions about method.

Consider some examples that most moderns have experienced. Let’s say you decide to lose weight or get in shape. One diet approach, the most frequent in the United States, is to focus on “how much” food you eat. The formula is simple: Cut Calories + Exercise More = Lose Weight. This view attempts to change your body by decreasing how much food you eat and increasing the amount of exercise you get. Quantity is the focus.

Another viewpoint emphasizes the quality of what you eat (e.g. no sweets or fats, more raw vegetables, fewer carbohydrates, etc.). This perspective holds that if you eat the right kinds of foods and cut out the “bad” foods you’ll get your desired result. Likewise, it suggests effective exercise, like certain weight-training routines, interval cardio workouts, or changing your exercise to keep your body constantly adapting. The emphasis here is on “how well” you eat or exercise rather than how much.

A combined perspective emphasizes both how much and how well you eat, exercise, study, sell or whatever you are trying to do. Most modern “how to” literature combines these, and there are many thousands of management, sales, health and other books and programs in many fields of life.

Only a few programs exist from the third perspective: method. This viewpoint cares less about “how much” or “how well” than about “how”. For example, it might recommend eating whatever you want, as much as you want, but chewing each bite 20 times and fully enjoying each mouthful. The fact that those who do this tend to eat a lot less (you get full with less food) and better food (when you really taste them, many junk foods lose their appeal), isn’t the point. The focus is on process or method. Again, this is less common than the quality and quantity approaches.

Another example is provided by college sports. One team might focus on getting the most fans (quantity), and consider this the measure of a successful sports program. More fans often means more money for the school, more donations, better community relations, and so on. Another school might emphasize getting the best, most talented, coaches and players (quality). A third might focus on the process of great practices, training, conditioning and preparation—trusting that doing the right things will bring the desired outcomes (method).

The most successful programs—like the most effective sales techniques, educational systems, and governments, etc.—will encourage all three: quantity, quality and method. If a team becomes the best recruiter in the nation but puts very little work into conditioning or practice, it will likely not win very often. On the other extreme, teams which ignore recruiting probably won’t flourish either. All three perspectives are needed.

Two more quick examples: Imagine a school or church which focuses only on numbers without regard to knowledge or truth, or exclusively on truth while refusing to share it with anyone. Few modern institutions seem to focus on greatness—on the methods and processes of, say, being a great student, a great teacher, or a great believer. The scientific method lends itself to experts, and it seems that in the wake of accepting this reality our society has decided to leave most issues of method to the specialists.

There are many examples of all three perspectives in business, science, art and beyond, and method remains a small minority in most fields. Quality and quantity rule the day. As stated above, this is the opposite of nearly all recorded history.

Let’s consider how these concepts apply to government. One way to measure the effectiveness of a government is how big or small it is (quantity). If it is too small, it is naturally weak, and it if it is too big it is naturally tyrannical—so argue the authors of The Federalist. A second viewpoint asks how “good” our leaders are, or how “effective” a government program is (quality). Both of these are legitimate ways to analyze our government.

A third perspective is to analyze government by process (method). For example, does it have a written constitution? Does this constitution separate the legislative, executive and judicial powers in a way that all three are independent, generally equal with each other in power, and effectively checked and balanced? Does this constitution separate (or fit into a separation of) national, provincial and more local governments—with most sovereign powers left to the lower governments and the people? Was this constitution ratified by the people? Do the regular people deeply understand this constitution today? Does the government always follow the constitution?

Any nation that does not follow these methods will not long maintain widespread freedom or prosperity. Free citizens who expect to remain free must carefully analyze and lead their government utilizing all three of these perspectives.

Unfortunately, nearly all current discussion of government centers around one thing—debates about the quality of our elected leaders and the effectiveness (or not) of various government programs. The quantity and method questions are seldom mentioned by anyone.

There are many examples of how this drastically impacts our freedom and prosperity. Consider taxes. Following the modern trend, most current debate about taxes centers on quantity (e.g. How much is too much?, How can government tax the people more?, or, Don’t we need to raise taxes to pay down our deficit?) or quality (e.g. Should we tax the wealthy or everyone equally?, or, Are income, sales or other kinds of taxes best?).

In contrast, the American founding generation used a method approach to taxes: Many kinds (quality) and levels (quantity) of taxes were constitutional, but the federal government could only assess taxes from the state governments—never from individuals or households. When we changed the method, we saw the rise of government that is too big, too inefficient and increasingly out of control.

This same argument (that we are mostly ignoring the method approach to government and that all three approaches are important) can be applied to many of our most pressing current issues, from education or health care to energy policy, immigration, fiscal and monetary decisions, the national debt and deficits, etc.

Quality government matters, certainly, but the quantity and method questions (especially method) are ultimately more important to the freedom and prosperity of the people. If the regular people want to remain free, they must understand and act on this.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Constitution &Culture &Economics &Education &Entrepreneurship &Government &Politics