Entrepreneurs of the World, Unite!

September 22nd, 2010 // 4:00 am @ Oliver DeMille

Click Here to Download a PDF of This Article

A revolution is needed.

Not just any revolution, mind you, but a specific kind of freedom shift that will make the critical difference.

In order to progress, we need a renaissance of the entrepreneurial mentality and many millions of entrepreneurs in our society.

The recession has already helped increase awareness of this need. The Information Age is naturally offering many improvements over the Industrial Age, but simple access to more information is not enough.

What we do with the increased power of widespread information is the key.

The great benefit of the Nomadic Age was family and community connection and a feeling of true belonging, while the Agrarian Age brought improved learning, science and art, and eventually democratic freedoms.

The Industrial Age allowed more widespread distribution of prosperity and social justice, and many improved lifestyle options through technological advances.

Unfortunately, during the Industrial Age many freedoms were decreased as free nations turned to big institutions and secretive agencies for governance.

The industrial belief in the conveyor belt impacted nearly every major aspect of life, from education and health care to agriculture, industry, business, law, media, family, elder care, groceries, clothing, and on and on.

Whether the end product was goods or services, these all became systemized on assembly lines—from production to delivery and even post-purchase customer service.

At the same time, we widely adopted certain industrial views which became cultural, such as “Bigger is always better,” “It’s just business,” “Perception is reality,” and many others. In truth, all of these are usually more false than true, but they became the cultural norm in nearly all of modern life.

Perhaps the most pervasive and negative mantra promoted by modernism is that success in life is built on becoming an employee and its academic corollary that the purpose of education is to prepare for a job.

Certainly some people want to make a job the focus of their working life, but a truly free and prosperous society is built on a system where a large number of the adult population spends its working days producing as owners, entrepreneurs and social leaders.

Producer vs. Employee Society

A society of producers is more likely to promote freedom than a society of dependents. Indeed, only a society of producers can maintain freedom.

Most nations in history have suffered from a class system where the “haves” enjoyed more rights, opportunities and options than the “have nots.” This has always been a major threat to freedom.

The American framers overcame this by establishing a new system where every person was treated equally before the law.

This led to nearly two centuries of increasing freedoms for all social classes, both genders and all citizens—whatever their race, religion, health, etc.

During the Industrial Age this system changed in at least two major ways.

First, the U.S. commercial code was changed to put limits on who can invest in what.

Rather than simply protecting all investors (rich or poor) against fraud or other criminal activity, in the name of “protecting the unsophisticated,” laws were passed that only allow the highest level of the middle class and the upper classes to invest in the investments with the highest returns.

This created a European-style model where only the rich own the most profitable companies and get richer while the middle and lower classes are stuck where they are.

Second, the schools at all levels were reformed to emphasize job training rather than quality leadership education.

Today, great leadership education is still the staple at many elite private schools, but the middle and lower classes are expected to forego the “luxury” of opportunity-affording, deep leadership education and instead just seek the more “practical” and “relevant” one-size-fits-all job training.

This perpetuates the class system.

This is further exacerbated by the reality that public schools in middle-class zip codes typically perform much higher than lower-class neighborhood schools.

Private elite schools train most of our future upper class and leaders, middle-class public schools train our managerial class and most professionals, and lower-class public schools train our hourly wage workers.

Notable exceptions notwithstanding, the rule still is what it is.

Government reinforces the class system by the way it runs public education, and big business supports it through the investment legal code.

With these two biggest institutions in society promoting the class divide, lower and middle classes have limited power to change things.

The Power of Entrepreneurship

The wooden stake that overcomes the vampire of an inelastic class system is entrepreneurial success.

Becoming a producer and successfully creating new value in society helps the entrepreneur surpass the current class-system matrix, and also weakens the overall caste system itself.

In short, if America is to turn the Information Age into an era of increased freedom and widespread economic opportunity, we need more producers.

How do we accomplish this Freedom Shift?

First of all, we must get past the obvious wish that Congress should simply equalize investment laws and allow everyone to be equal before the law.

Neither government nor big business has a vested interest in this change, and neither, therefore, does either major political party.

Nor does either side see much reason to change the public education system to emphasize entrepreneurial over employee training.

Either of these changes, or both, would be nice, but neither is likely.

What is more realistic is a grassroots return to American initiative, innovation and independence.

Specifically, regular people of all classes need to become producers.

A renaissance of entrepreneurship (building businesses), social entrepreneurship (building private service institutions like schools and hospitals), intrapreneurship (acting like an entrepreneur within an established company), and social leadership (taking entrepreneurial leadership into society and promoting the growth of freedom and prosperity) is needed.

Along with this, parents need to emphasize personalized, individualized educational options for their youth and to prepare them for entrepreneurship and producership, rather than cultivating in them dependence on employeeship.

If these two changes occur, we will see a significant increase in freedom and prosperity.

The opposite is obviously true, as well: The long-anticipated “train wreck” in society and politics is not so difficult to imagine as it was twenty years ago.

The education of the rising generation in self-determination, crisis management, human nature, history, and indeed, the liberal arts and social leadership in general, is the historically-proven best hope for our future liberty and success.

If entrepreneurial and other producer endeavors flourish and grow, it will naturally lead to changes in the commercial code that level the playing field for people from all economic levels and backgrounds.

Until the producer class is growing, there is little incentive to deconstruct the class system.

More than 80 percent of America’s wealth comes from small businesses, and when these grow, so will our national prosperity.

Today there are numerous obstacles to starting and growing small businesses. There will be many who lament that the current climate is not friendly to new enterprises.

Frontiers have ever been thus, and our forebears plunged headlong into greater threats. What choice did they have? What choice do we have? What if they hadn’t? What if we don’t?

The hard reality is that until the producer class is growing there will be little power to change this situation.

As long as the huge majority is waiting for the government to provide more jobs, we will likely continue to see increased regulation on small business that decreases the number of new private-sector jobs and opportunities.

The only realistic solution is for Americans to engage their entrepreneurial initiative and build new value.

This has always been the fundamental source of American prosperity.

The Growing Popularity of Producer Education

Consider what leading thinkers on the needs of American education and business are saying.

In Revolutionary Wealth, renowned futurist Alvin Toffler says that schools must deemphasize outdated industrial-style education with its reliance on rote memorization, the skill of fitting in with class-oriented standards, and “getting the right answers,” and instead infuse schools with creativity, individualization, independent and original thinking skills, and entrepreneurial worldviews.

Harvard’s Howard Gardner argued in Five Minds for the Future that all American students must learn the following entrepreneurial skills: “the ability to integrate ideas from different disciplines or spheres,” and the “capacity to uncover and clarify new problems, questions and phenomena.”

John Naisbitt, bestselling author of Megatrends, wrote in Mind Set! that success in the new economy will require the right leadership mindset much more than Industrial-Age credentials or status.

Tony Wagner wrote in The Global Achievement Gap that the skills needed for success in the new economy include such producer abilities as: critical thinking, problem solving, collaboration, leading by influence, agility, adaptability, curiosity, imagination, effective communication, initiative and entrepreneurialism.

Former Al Gore speechwriter Daniel Pink writes in A Whole New Mind that the most useful and marketable skills in the decades ahead will be the entrepreneurial abilities of high-concept thinking and high-touch leading.

Seth Godin makes the same case for the growing need for entrepreneurial-style leaders in his business bestsellers Tribes and Linchpin.

Malcolm Gladwell arrives at similar conclusions in the bestselling book Outliers.

There are many more such offerings, all suggesting that the future of education needs to emphasize training the rising generations to think and act like entrepreneurs.

Indeed, without a producer generation, the Information Age will not be a period of freedom or spreading prosperity. Still, few schools are heeding this research.

CNN’s Fareed Zakaria has shown in The Post-American World that numerous nations around the world are now drastically increasing their influence and national prosperity.

All of them are doing it in a simple way: by incentivizing entrepreneurial behavior and a growing class of producers.

Unlike aristocratic classes, successful entrepreneurs are mostly self-made (with the help of mentors and colleagues) and have a deep faith in free enterprise systems, which allow opportunity to all people regardless of their background or starting level of wealth.

Entrepreneurs and Freedom

History is full of anti-government fads, from the French and Russian revolutionists to tea-party patriots in Boston and anti-establishment protestors at Woodstock, among many others. Some revolutions work, and others fail.

The ones that succeed, the ones that build lasting change and create a better world, are led by entrepreneurial spirit and behavior. As more entrepreneurs succeed, the legal system naturally becomes more free.

As more people take charge of their own education, utilizing the experts as tutors and mentors but refusing to be dependent on the educational establishment, individualized education spreads and more leaders are prepared.

With more leaders, more people succeed as producers, and the cycle strengthens and repeats itself.

Freedom is the result of initiative, ingenuity and tenacity in the producer class. These are also the natural consequences of personalized leadership education and successful entrepreneurial ventures.

For anyone who cares about freedom and wants to pass the blessings of liberty on to our children and grandchildren, we need to get one thing very clear: A revolution of entrepreneurs is needed.

We need more of them, and those who are already entrepreneurs need to become even better social leaders. Without such a revolution, freedom will be lost.

Click Here to Download a PDF of This Article

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is the founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

He is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Education &Entrepreneurship &Featured &Government &History &Information Age &Liberty &Producers

Save the Cheerleader

September 21st, 2010 // 4:00 am @ Oliver DeMille

In our current two-party system, independents need the two big parties.

There is, of course, an Independent Party, and people have differentiated members of this party from independents by using the phrase “small ‘I’ independents” to denote those who aren’t part of any party.

Few independents have any interest in joining a third party. They consider this a worse option than signing up as a Democrat or Republican.

Most independents share a frustration with both major parties, and they see partisanship itself as symptomatic of America’s problem. Independents especially dislike the political wrangling of party battles.

But let’s get one thing clear: In nearly all elections, most independents end up voting for a candidate from one of the two big parties.

There are several lessons to be learned from this.

Let’s Party!

First, independents need the parties.

Perhaps a non-party arrangement like the one envisioned by America’s founding fathers will someday offer a better system. Or maybe independents will eventually take over one of the major parties.

But in our current system, independents need the parties to be and do their best. Independents need to be able to choose between the highest caliber of candidates and policies, and the sheer numbers affect both the ability to get a message out, and the ability to attract willing candidates.

Bottom line: the parties are still providing the available options for our votes.

Second, the two-party system needs independents.

When the big parties hold a monopoly on political dialogue and innovation, centrist members of both parties congeal together a great deal and the parties often seem more alike than different.

Throw large numbers of independents into the mix, however, and the parties are forced to energetically debate their platform and the weaknesses of their opposition’s candidates, policies and so forth.

They have to articulate their message more clearly and differentiate themselves in order to garner independent votes.

Ironically, as much as independents abhor political fighting, it is by contrasting themselves with such “vulgarity” that thoughtful, idealistic and principled independents define themselves.

Not as a group, of course—but as individuals who are independent of and above the disingenuous and exploitive methods and motivations they believe typify the party loyalists.

The noisy and unproductive debate is the point to which independents are counter-point.

At the same time (and this is point number three), the strong influence of independents keeps either party from obtaining too much power for long.

Studied, serious-minded citizens who think and act independently and make their influence felt are exactly the type of citizens the American founders hoped would populate the republic.

Party loyalties too often reduce this level of independence. At their best, independents function as much-needed checks and balances on the two-party system that has become too powerful.

Party People

The independents need the parties, and the two-party system needs the independents.

But a fourth lesson might be the most important. The individual parties themselves actually need independents.

Political parties are only as strong as their collective members, and there are certain types of members that are extremely valuable to party influence.

For example, parties benefit from Traditionalist members—people who were raised with passionate loyalties to Democrats or Republicans.

Such members nearly always vote for the party and its candidates, and often they cast straight party votes without seriously considering other options. Their allegiance to the long view of Party dominance overshadows their concerns and even outright disagreements with the Party.

Politicos are a second important group of members in any party.

Politicos love politics. They watch it with as much interest and passion as dedicated sports fans follow their team. Politicos listen to party leaders, think about and memorize talking points (often unconsciously), and promote the party line. They also study lots of literature debunking the other party and pass along these arguments.

A third type found in both parties is the Intellectual. Intellectual Partyists are distinguished most by their habits of skepticism and asking questions. They consider party literature mere propaganda and instead search out and study original sources.

Intellectuals typically read opposing party sources as much or more as works from their own party.

Policy Wonks are a fourth type in any party, and they care most about specific proposals, plans and models, and enjoy studying them in detail, discovering patterns and flaws, and creating counter-proposals and solutions.

They examine, scrutinize, analyze, write and attend lots of seminars, panels and other events filled with discussion. Most of them make their living doing this in academia, media, punditry, the lecture circuit or blogosphere, or the like.

Party Leadership

A fifth type of party people, Activists, are usually familiar with the other types but they put most of their effort into influencing state or federal legislative votes, agency policies, judicial cases or executive acts.

They are found at all levels of government from local to international organizations. Some of them put most of their focus into elections.

Party Officios, a sixth type of party promoters, hold party positions (voluntary and informal as well as official) in local precincts all the way up to national committees.

Some are full-time paid professionals or experts, but the large majority of them voluntarily serve as officers, delegates, candidates, unofficial advisors and other roles in the party.

Among party Officios are those holding office. These elected and appointed officials represent their party in specific positions of public service.

Seventh and eighth types are Donors and Fundraisers. They of course play important roles in all parties, since politics is expensive and funding often significantly influences policy and elections.

There are various other types of people that help parties succeed, but the most influential type of all is the people who could simply be called “Majorities.”

The obvious power of Majorities is that they have the numbers and therefore the votes to steer the party. They elect the delegates who elect the party candidates, and their influence is deeply and widely felt in general elections.

Majorities are mostly made up of regular, non-politician, thinking citizens who have the most influence on party delegates, general donations and the general voters.

Majority types are usually not Traditionalists, Politicos, Officios, Wonks or political experts.

But they keep track of what is happening in society and think seriously about political concerns, issues and elections. They spread their influence day after day and impact thinking widely and consistently.

The media is seldom able to predict close elections because of this wildcard: Since Majorities’ type of engagement is largely internal and interpersonal, and because their influence is largely in a realm that is under-valued (or perhaps beyond the control of) those in power, it is almost impossible to know what Majorities are really thinking and to predict how they will impact outcomes.

Save the Cheerleader

So why do the parties need independents?

At first glance, it might appear that the parties would do better if independents would just split and join the big parties.

But a deeper analysis shows how significant the growth of independents has become.

Independents aren’t just the new numerical majority; they are the barometer of success.

As a type, independents aren’t Traditionalists, Politicos or Officios. Most of them are Majorities, and a lot of them are Wonks.

In short, they care little about the future of the party, and a lot about helping both people in particular, and the nation in general.

Parties need the votes of independents, but they need something more. The two big parties both need independent Majorities.

When they are receiving independent support, they know that they are probably on track. Or, when they lose independents, they know to step back reevaluate their direction.

There are certainly times when government officials need to ignore independents and everyone else and stand firm on the right path.

But most times they can pretty much tell how well they are doing by finding out what the independents are thinking.

Of course, independents aren’t always right. But they are right more often than the big parties because in general, they care more about the nation than about party power. Madison and Jefferson would applaud.

This is a great benefit to both parties. In some ways, independents have made it easy for politicians. Win the independents, win the election.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is the founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

He is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Government &Independents &Politics

Independents & the Tea Party Movement

September 20th, 2010 // 4:00 am @ Oliver DeMille

Click Here to Download a PDF of this Article

Much of the media represents what it calls a “third” view as sometimes independents and other times the Tea Party.

In recent elections, these two groups have often voted together. They both tend to vote against entrenched power, and they both support better fiscal discipline from our leaders.

Beyond these two similarities, however, they bear little resemblance.

The Tea Party is angry at Washington. Independents want to see Washington get its act together.

The Tea Party is comparatively extreme in its views and strident in the tone of its arguments. Independents are typically moderate in viewpoint as well as methodology.

A majority of Tea Party supporters are former Republicans who feel disenfranchised from the GOP. Independents come from all parts of the political spectrum.

Tea Party enthusiasts tend to promote “revolution”—although their platform is more clearly defined by what they object to than by what they propose to do about it. Independents want substantive and tenable reform.

Tea Party crowds often act like football fans during big rivalry games. Independents most often talk like accountants analyzing today’s financials.

The Tea Parties want big, symbolic, massive change. They’re pretty clear on whom they think is to blame for America’s problems and they frequently recur to name-calling and sarcasm to make their point. Independents want certain policies to be passed that significantly improve government and society.

Tea Party supporters see themselves as part of a big fight, and they want to win and “send the bad guys packing.” Independents want the fighting, name calling, mudslinging and partisan wrangling to stop and for our leaders to just sit down together and calmly work up solutions to our major national challenges.

Voting

Tea Parties are bringing out more conservative voters to take on the Democratic majority. Independents are voting against Democrats right now because they want to see real progress, just like they voted against Republicans during much of the last decade.

If the Republican Party swings right, most of the Tea Partiers will consider their work done. If the Republican Party swings right, most independents will give it far less support.

Tea Parties are viscerally against liberalism. Independents will vote against Democrats on some issues and against Republicans on others, always throwing their support behind the issues and projects they think will best help America.

Few Tea Partiers voted for Obama. Many independents did. A lot of Tea Partiers see Sarah Palin as a viable presidential candidate. Hardly any independents support Palin or consider her a viable candidate for high federal office. Most Tea Party members vehemently disliked Ted Kennedy. Many independents like him a lot.

Many Tea Party supporters want Obama to fail, and in fact believe that he has already failed. A majority of independents are frustrated with President Obama’s work so far but sincerely hope he will turn it around by shifting his focus and adopting what they consider moderate and needed changes.

The Tea Party tends to compare Obama to the likes of Hitler, while most independents admire and like Obama personally even while disagreeing with the substance of some of his policies.

In short, Tea Partiers and independents aren’t cut from the same cloth and actually have very little in common. But, as mentioned, they have been voting together for the last six months and will likely continue to do so for some time ahead.

That being said, they are unlikely to stay connected in the long term. Of course, there are a number of independents who have aligned themselves with the Tea Party or Tea Party events in order to have an impact right now.

That’s what independents do.

How Populism Succeeds

Which group [independents or the Tea Party] is most likely to last? The answer probably depends on upcoming elections.

The Tea Parties are a populist movement, meaning that their popularity requires at least three things:

- An agreed upon enemy with enough power to evoke strong fears, anger and emotion

- An upcoming event to rally around, such as elections or national seminars

- A sense that they can actually change everything quickly and drastically

The first and second factors will stay around as long as a Democrat is in the White House.

Tea Party fervor may be lessened by the midterm elections if, and only if, a lot of Democrats lose—but will likely resurge again as the next presidential election nears.

The third requirement is what has generally doomed all historical populist movements. The Tea Party revolt is new and may gain energy. But things will change as soon as one major (and inevitable) event occurs.

When the Tea Party wins a major election and then watches its newly-elected candidates take office and join the system, it will turn its energy from activism to cynicism and lose momentum.

If those the Tea Party elects make a splash and take on the establishment, or symbolically seem to do so, the Tea Partiers will breathe easy, congratulate themselves on their victory and go back to non-political life.

If the new officials make few changes and Washington seems as bad as ever, many Tea Party enthusiasts will lose faith and give up on activism. More on this later.

The History of Conservative Populism

This series of events is cyclical, and the pattern has repeated itself many times. The Anti-Federalists, Whigs and Moral Majority all, in their day, fizzled out on this cycle.

Likewise, “constitutionalism” arose during the 1960’s, gained influence with publications and seminars in the 1970’s, and culminated in the election of Ronald Reagan.

After his inauguration, most constitutional organizations saw their donations and budgets halved—or worse—and many disappeared. The term “constitutionalist” lost it power—indeed, became a label for energetic irrelevance—and the nation moved on.

After Reagan, Rush Limbaugh increased in popularity and influence leading up to and throughout the Clinton years, and his radio show became the rallying point of conservative populism.

The press worried about the growing power of talk radio and both major political parties listened daily to Limbaugh’s commentary and strategized accordingly.

“Dittoheads” (Limbaugh fans) saw Clinton as the great enemy and rallied around elections, the Contract with America, and (between elections) Limbaugh’s show.

But with the election of Republican George W. Bush, Dittohead Nation congratulated itself on victory and mostly turned to non-political life. Today there is little excitement about or commentary on becoming a Dittohead.

It should be acknowledged that conservative populist movements have often added positive ideas to the national discussion and many of its leaders have helped raise awareness of freedom and promote citizen involvement.

In this sense, Anti-Federalists, Whigs, the Moral Majority, Constitutionalists, Dittoheads and the Tea Parties are not insignificant to American politics. They have had, and likely still will, huge impact.

Liberal vs. Conservative Populism

Note, in contrast [to conservative populism], that liberal populism typically follows a different path.

Movements such as Abolition, Feminism, Civil Rights and Environmentalism build and build until they are legislated. At that point, liberal populists get really serious and set out to expand legislation.

Not being saddled with trying to establish a negative, liberal populists don’t lose momentum like conservative populists—because the liberal objective isn’t to stop something but rather to achieve specific goals.

The challenge of conservative populism is that its proponents are, well, conservative. They see life as fundamentally a private affair of family, career and personal interests.

To the conservative, political activism is a frustrating, anomalous annoyance that shouldn’t be necessary—an annoyance that sometimes arises because of the actions of “bad” people abusing power.

The conservative soul idealizes being disengaged from political life; as a result, conservative populism is doomed to always playing defense.

The conservative will embrace politics when to continue to avoid politics poses a clear and present danger.

When conservatives engage politics in popular numbers, they do so in order to “fix things” so they can go back to not thinking about government.

The liberal soul, on the other hand, sees political life as a part of adulthood, natural to all people, and one of the highest expressions of self, society, community and the social order—not to mention a great deal of fun.

Many liberals greatly enjoy involvement in governance. The liberal yearns for participation in society, progress and politics.

They care about family and career as much as conservatives, of course, but many liberals consider involvement in politics to be at the same level of importance as family and work.

The Future of Tea & Independents

Tea Parties will likely grow and have impact for some years, but they are unlikely to become a long-term influence beyond Obama’s tenure.

In contrast, independents may well replace one of the major parties in the decades ahead.

Few independents are populists and are therefore not swayed by the political media or party politics. They watch Fox and MSNBC with equal skepticism, and prefer to do their own research on the detailed intricacies of the issues.

They generally distrust candidates and officials from all parties, believing that politics is a game of persuasion and spin.

Also: Independents really do stand for something. They want government to work. They want it to provide effective national security, good schools, responsible taxes and certain effective government programs.

Like conservatives, independents want government to spend less and stop trying to do too much. Like liberals, independents want government to tackle and fix our major challenges and where helpful to use effective government programs.

Independents want health care reformed, and they want it done in common-sense ways that really improve the system. They apply this same thinking to nearly all major issues.

Like many liberals, a lot of independents enjoy closely watching and participating in government. They take pleasure in activism and involvement. They prioritize political participation up there with family, career and personal interests.

All indications are that the Tea Parties are a short-term, albeit significant, movement, while the power of independents will be here for a long time ahead.

When the current political environment shifts and conservative populists lose their activist momentum, independents will still be studying the issues and making their views known.

In fact, a serious question now is whether the Republican and Democratic parties can both outlast the rise of independents. The answer is very likely “no.”

Click Here to Download a PDF of this Article

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is the founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

He is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Current Events &Government &History &Independents &Politics

The Latch-Key Generation & Independents

September 16th, 2010 // 4:00 am @ Oliver DeMille

The rise of Independents isn’t an accident. It is the natural result of both major parties emphasizing politics over principle and ideology over pragmatism.

A third reason for the rise of Independents is the widespread loss of blind faith in man-made institutions (like government and corporations) as the answers to society’s challenges.

These institutions have failed to perform, over and over, causing many of even the staunchest state- and market-loyalists to feel skeptical.

Fourth, the e-revolution has created a technological power of the citizenry, at least in the ability to widely voice views that diverge from the mainstream parties.

The Internet gave Independents (and many others) a voice. People who believed in common-sense pragmatism and principled choices over party loyalty have been around for a long time, but the e-revolution was needed to give them group influence.

But all of these reasons are really just after-the-fact justifications for why so many people are no longer channeled politically through one of the top parties.

They explain why people aren’t Republicans or Democrats, but they don’t explain why Independents are Independents.

Some Independents are actually from the far right and just anti-liberal, and others are leftists who are Independents because they are anti-conservative. Some are one-issue Independents, emphasizing the environment, feminism, race, the gold standard, etc.

A growing number of Independents, however, are Independents because they believe in a shared new ideal.

They have faith in both government and the market, but only to a certain extent. They are truly neither liberal nor conservative, but moderate. They want government and markets to work, and they want to limit both as needed.

Still, they are not just moderates, they are something more.

Three Versions of Management

What makes these Independents tick? They are motivated by a new focus, a set of goals surprising and even confusing to anyone who was taught that American politics is about right versus left, conservative versus liberal, family values versus progressivism, religious versus secular, hawk versus dove, and all the other clichés.

Independents are something new.

Daniel Pink argues that business is going through a major shift, that the entire incentive landscape of employees, executives and even owner-investors is changing.

Our ancestors were motivated mostly by “Management 1.0,” Pink says, which was a focus on physical safety and protection from threats.

“Management 2.0” came when people learned to produce things in a routine way, from planned agriculture to industry.

People became more motivated by a “carrot-and-stick” model of “extrinsic motivators.” Managers, teachers, parents and politicians created complex systems of rewards and punishments, penalties and bonuses to achieve results in this new environment.

In this model, conservatives are 1.0 because they want government to limit itself to protecting its citizens from external threats, to national security and legal justice.

Liberals support a 2.0 model where the role of government is to incentivize positive community behaviors by people and organizations, and also to enforce a complex system of punishments to deter negative behavior.

In education, 1.0 is the one-room schoolhouse focusing on delivering a quality, personalized education for each student.

In contrast, 2.0 is a conveyor-belt system that socializes all students and provides career rewards through job training, with benefits doled out based on academic performance.

The problem with 1.0 is that education is withheld from some based on race, wealth and sometimes gender or religion.

The 2.0 version remedies this, ostensibly providing democratic equality for students from all backgrounds; but the cost is that personalization and quality are lost, and a de facto new elite class is created by those who succeed in this educational matrix.

On the political plane, 1.0 promoted freedom but for an elite few, while 2.0 emphasized social justice but unnecessarily sacrificed many freedoms.

Version 3.0 combines freedom with inclusion, and this is the basis of the new Independents and their ideals.

It may seem oxymoronic to say that pragmatic Independents have ideals, but they are actually as driven as conservatives and liberals.

Independents want government, markets and society to work, and to work well. They don’t believe in utopia, but they do think that government has an important role along with business, and that many other individuals and organizations have vital roles in making society work.

They aren’t seeking perfect society, but they do think there is a common sense way in which the world can generally work a lot better than it does.

Mr. Pink’s “Management 3.0” is a widespread cultural shift toward “intrinsic motivators.” A growing number of people today (according to Pink) are making decisions based less on the fear of threats (1.0), or to avoid punishments or to obtain rewards (2.0), than on following their hearts (3.0).

This isn’t “right-brained” idealism or abstraction, but logic-based, rational and often self-centered attempts to seek one’s most likely path to happiness.

Indeed, disdain for the “secure career path” has become widely engrained in our collective mentality and is associated with being shallow, losing one’s way, and ignoring your true purpose and self.

This mindset is now our culture. For example, watch a contemporary movie or television series: The plot is either 1.0 (catch or kill the bad guys) or 3.0 (struggle to fit in to the 2.0 system but overcome it by finding one’s unique true path).

Settling for mediocrity in order to fit the system is today’s view of 2.0.

In contrast, the two main versions of 3.0 movies and series are: 1) Ayn Rand-style characters seeking personal fulfillment, and 2) Gene Rodenberry-style heroes who “find themselves” in order to greatly benefit the happiness of all.

Where the Greeks had tragedy or comedy, our generation finds itself either for personal gain or in order to improve the world.

Whichever version we choose, the key is to truly find and live our life purpose and be who we were meant to be.

And where so far this has grown and taken over our pop-culture and generational mindset, it is now poised to impact politics.

Few of the old-guard in media, academia or government realize how powerful this trend is.

Generations

Independents are the latch-key generation grown up.

Raised by themselves, with input from peers, they are skeptical of parents’ (conservative) overtures of care after years of emotional distance.

They are unmoved by parents’ (liberal) emotional insecurity and constant promises. They don’t trust television, experts or academics.

They don’t get too connected to any current view on an issue; they know that however passionate they may feel about it right now, relationships come and go like the latest technology and the only one you can always count on is yourself.

Because of this, you must do what you love in life and make a good living doing it. This isn’t abstract; it’s hard-core realism.

Loyalty to political party makes no sense to two generations forced to realize very young the limitations of their parents, teachers and other adults.

Why would such a generation give any kind of implicit trust to government, corporations, political parties or other “adult” figures?

Independents are more swayed by Google, Amazon and Whole Foods than Hollywood, Silicon Valley or Yale.

Appeals to authority such as the Congressional Budget Office, the United Nations or Nobel Prize winners mean little to them; they’ll study the issues themselves.

Their view of the experts is that whatever the outside world thinks of them, they are most likely far too human at home.

Officials and experts with noteworthy accolades, lofty credentials and publicized achievements make Independents more skeptical than star-struck.

They grew up with distant and distracted “corporate stars” for parents, and they aren’t impressed.

Having moved around throughout their formative years, never allowed to put down deep roots in any one town or school for long, why would they feel a powerful connection to country or nation?

If the government follows good principles, they’ll support it. If not, they’ll look elsewhere.

They understand being disappointed and having to move on and rely on themselves; in fact, this is so basic to their makeup that it is almost an unconscious religion.

If this all sounds too negative, consider the positives. The American founding had many similar generational themes.

Raised mostly by domestic help (parents were busy overcoming many out-of-the-home challenges in this generation), sent away to boarding schools or apprenticeships before puberty, the founders learned loyalty to principles over traditions, pragmatic common sense over the assurances of experts, and an idealistic yearning for improving the world over contentment with the current.

Today’s Independents are one of the most founders-like generation since the 1770s. They want the world to change, they want it to work, and they depend on themselves and peers rather than “adults” (experts, officials, etc.) to make it happen.

Independent Philosophy

There are many reasons why Independents don’t resonate with the two major parties, but this is only part of the story.

Most Independents aren’t just disenfranchised liberals or conservatives; they are a new generation with entirely new goals and views on government, business and society.

This is all hidden to most, because the latch-key generation isn’t vocal like most liberals and conservatives.

Trained to keep things inside, not to confide in their parents or adults, growing numbers of Independents are nonetheless quietly and surely increasing their power and influence.

Few Independents believe that there will be any Social Security monies left for them when they retire, so they are stoically planning to take care of themselves.

Still, they think government should pay up on its promise to take care of the Boomers, so they are happy to pay their part. Indeed, this basically sums up their entire politics.

They disdain the political debate that so vocally animates liberals and conservatives, and as a result they have little voice in the traditional media because they refuse to waste time debating.

But their power is drastically increasing. The latch-key Independents raised themselves, grew up and started businesses and families, and during the next decade they will increasingly overtake politics.

Like Shakespeare’s Henry V, they partied through the teenager stage, leaving their parents appalled by generational irresponsibility and lack of ambition, then they shocked nearly everyone with their ability and power when they suddenly decided to be adults.

Now, on eve of their entrance into political power, few have any idea of the tornado ahead.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is the founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

He is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Business &Culture &Current Events &Generations &Government &Independents &Politics &Technology

America’s Seven-Party System

September 9th, 2010 // 12:23 pm @ Oliver DeMille

High school civics classes for the past century have taught that America had a two-party system.

And up until the end of the Cold War, this was true. Each party had clear, distinct values and goals, and voters had simply to assess the differences and choose which to support.

Such clarity is long gone today, and there is no evidence that this will change any time soon.

As a result, more people now call themselves “Independents” than either “Democrats” or “Republicans.”

We are led today by the contests and relations of seven competing factions, or parties. These major factions are as follows:

Republicans

1. Nixonians

2. Reaganites

3. Populists

Democrats

4. Leftists

5. Leaders

6. Special Interests

Either/Neither

7. Independents

Neither party knows what to do about this. Both are plagued by deep divisions. When a party wins the White House, these divisions are largely ignored.

During a Party’s time in the White House, the underpinnings of the party weaken as differences are downplayed and disaffection quietly grows.

Fewer people wanted to be identified as Republicans with each passing year under the Bush administration, just as the Democratic coalition weakened during the Clinton years.

This is a trend with no recent exceptions. Being the party in power actually tends to weaken popular support over time.

Governance v. Politics

The emerging and improving technologies of the 1990s and 2000s have reinvented government by forcing leaders to constantly serve two masters: governance and politics.

Governance is a process of details and nuance, but politics is more about symbols than substance.

As I stated in The Coming Aristocracy, before the past two decades politics were the domain of elections, which had a compact and intense timeline.

After elections, officials had a period to focus on governing, and then a short time before the subsequent elections they would return to politics during the campaign period.

Now, however, governors, legislators and presidential administrations are required to fight daily, year-round, on both these fronts.

Both major parties struggle in this new structure. Those in power must dedicate precious time and resources to politics instead of leadership.

Worst of all, decisions that used to be determined at least some of the time by actual governance policy are now heavily influenced by political considerations, almost without exception.

Power facilitates governance, but reduces political strength. Every governance policy tends to upset at least a few supporters, who now look elsewhere for “better” leadership.

While Republicans and Democrats accomplish it in slightly different ways, both alienate supporters as they use their power once elected.

The Loyal Opposition

The party out of power has less of a challenge, but even it is expected to present alternate governance plans of nearly everything — plans which have no chance of ever being adopted and are therefore a monumental misuse of official time and energy — instead of focusing on their vital role of loyal opposition which should ensure weighty and quality consideration of national priorities.

The temptation to politicize this process is nearly overwhelming — meaning that the opposition party has basically abandoned any aspiration or intent to participate in the process of governing and become all-politics, all-the-time.

As a result, American leadership from both parties is weakened.

With the advancement of technology in recent years has come the increased facility for individuals to not only access news and information in real time, but to participate in the dialogue by generating commentary, drawing others’ attention to under-reported issues and ideas and influence policy through blogging, online discussions and grassroots campaigns.

An immensely important consequence of this technological progress has been the fractionalizing of the parties.

Republicans: The Party of Nixon vs. The Party of Reagan

Both Nixon and Reagan were Republicans, but symbolically they are nearly polar opposites to all but the most staunch Republican loyalists.

Reaganites value strong national security and schools, fiscal responsibility, and laws which incentivize small businesses and entrepreneurial enterprises.

Nixonians value party loyalty over ideology, government policy that benefits big business and large corporations, international interventionism and winning elections.

A third faction in the Republican community are the populists.

Feeling disenfranchised by the loss of the Party to the Nixonians, the populists want Americans to “wake up,” realize that “everything is going socialist,” and “take back our nation.”

Identified with and defined by talk-show figureheads with shrill voices, the populists are seen as more against than for anything. They believe that government is simply too big, and that anything which shrinks or stalls government is patently good.

A Bad Day To Be A Populist

The populists are doomed to perpetual disappointment, since any time they win an election they watch their candidate “sell out.”

It is hard to imagine a more thankless job than that of the candidate elected by populist vote; once she takes office she is consigned to offend and alienate either her constituents or her colleagues — most likely both.

She is either completely ineffective at achieving the goals of her constituency, or, if she learns to function within the machine, she has no constituency left.

Any candidate who tries to work within the system will lose her appeal to the populists.

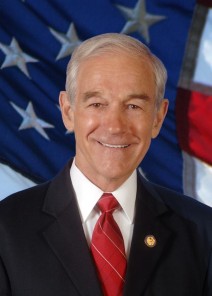

If such a candidate stays focused on principle, like the iconic Ron Paul, many populists will admire his purity but will criticize his lack of substantive impact — his accomplishments are seen as almost exclusively symbolic.

If such a candidate stays focused on principle, like the iconic Ron Paul, many populists will admire his purity but will criticize his lack of substantive impact — his accomplishments are seen as almost exclusively symbolic.

Some of the most influential populist pundits (like Rush Limbaugh) have lost “believers” by being outspokenly populist when it supports the party agenda (like during the Clinton Administration and later in rejecting McCain’s presidential candidacy as too moderate/liberal) and then switching to support the Party (backing President Bush even in liberal policies and supporting McCain when he became the Republican nominee).

This is seen by detractors as manipulative, corrupt and Nixonian at worst, and self-serving, hypocritical and opportunist at best.

Vast Right Wing Conspiracy

Populism is considered “crazy” by most intellectuals in the media and elsewhere.

This is probably inevitable and unchangeable given that the same things which appeal popularly (such as alarmism, extremism, labeling, using symbols, images, hyperbole and appeals to sentimentalism) are considered anti-truth to intellectuals.

Indeed, part of training the intellect in the Western tradition is to reject the message of such deliveries without serious consideration, and dismiss the messenger as either unfit or unworthy to have a serious debate on issues.

Wise intellectuals look past the delivery and consider the actual message. This being said, even when weighed on its own merit the populist message is unpopular with intellectuals.

Populism is based on the assumption that the gut feelings of the masses (The Wisdom of the Crowds) are a better source of wisdom than the considered charts, graphs and analysis by teams of experts.

This hits very close to home for those who make their living in academia, the media or government. So our system seems naturally to pit the will of the people against the wisdom of the few.

Crazy Like a Fox

It is interesting to compare and contrast this modern debate between the wisdom of the populists and that of experts and officials with the American founding view.

The brilliance of the founders was their tendency to correctly characterize the tendencies of a group in society and employ that nature to its best use in the grand design in order to perpetuate freedom and prosperity.

In fact, the American framers did empower the masses to make certain vital decisions through elections. Madison rightly called every election a peaceful revolution.

And, the founders did empower small groups of experts: the framers had senators, judges, ambassadors, the president and his ministers appointed by teams of experts.

Only the House of Representatives and various state and local officials were elected by the masses, and the House alone was given power over the money and how it was spent.

In short: The founders thought that the masses would best determine two things:

1. Who should make the nation’s money decisions, and

2. Who should appoint our other leaders.

Riddle: When Is A Democracy Not A Democracy?

The founders believed that most of the nation’s governance should come from teams of experts, as long as the masses got to decide who would appoint those experts and how much money they could spend.

Such a system naturally empowers and employs both populism and expertise.

If It’s Not Broken, Don’t Fix It

Compare today’s model: Senators are now elected by the populace and the electoral college has been weakened so that the popular vote has much more impact on electing a president than it once did (and than the founders intended), thus increasing the power of the popular vote.

Yet many of the same intellectuals who support ending the electoral college altogether ironically consider populists “crazy” and “extremist.” The incongruity is so extreme that is no wonder many conclude that there must be some dark, conspiratorial agenda driving this trend.

Talking Heads

The reason for this seeming paradox is simple: Where the founding era actually believed in the wisdom of the populace to elect, modern intellectuals seem to believe that few of these “crazies” actually believe what they say they believe.

Many intellectuals think that populists, conservatives and most of the masses are simply following the views provided by talking heads.

For them, populist “wing nuts” have been duped by the sophistries of Rush Limbaugh, Bill O’Reilly, Glenn Beck, Sean Hannity, Ann Coulter, or some other “self-serving anti-intellectual.”

But at its core, the alarmist and wild antics of populist pundits are not the real reason many intellectuals question the sanity of conservative populists.

The deeper reason is that few intellectuals believe that sane people don’t want more government.

They understand Nixonian Republicans and their desire for more power, government support of Big Business and less regulation of corporations. They may not agree with these goals, but they understand them.

They also understand poor and middle class citizens wanting more government help.

And they even understand the Reaganesque vision of fiscal responsibility along with strong schools, security and increased incentives for small business.

Does No Mean Yes?

What intellectuals struggle to understand is lower and middle class voters who don’t want government programs.

For example, few of the populist “crazies” who oppose President Obama’s health care would be taxed to pay for it, and most would see their family’s health care benefits increased by Democratic plans.

So why would they — how could they — oppose it?

Rich right-wing leaders who would bear the costs for health care must have convinced them.

This is a logical conclusion. Rich people opposing higher taxes makes sense. Lower and middle class people supporting increased government aide makes sense.

Rich talk show hosts telling people Obama’s plan is bad makes sense. The people being duped by this makes sense.

What doesn’t make sense, what few intellectuals are willing to accept, is that large numbers of non-intellectuals are looking past alarmist talk show host antics, closely studying the issues and deciding to choose the principles of limited government over direct, personal, monetary benefit.

Intellectuals could respect such a choice; lots of citizens refusing government benefits to help the nation’s economy and freedom would be an amazing, selfless act of patriotism.

But they don’t believe this is happening.

Instead, they are concerned that the “wing nuts” are following extremist pundits and unknowingly refusing personal benefit. That’s “crazy”!

This view is reinforced by the non-intellectual and often wild-eyed way some populists act and talk about the issues.

In this same vein, intellectuals also naturally support the end of the electoral college because it would naturally give them, especially the media, even more political influence.

The most frustrating thing for intellectuals is this: The possibility that these “crazies” aren’t really crazy at all — that they actually see the biased focus and struggle for power by the intellectual media and don’t want to be duped by it.

Such a segment of society naturally diminishes the potential influence of the media, and is treated by many as a threat.

By the way, many conservative populists claim to be Reaganites. In fairness, they do align with a major Reagan tenet — an anti-incumbent, anti-Washington, anti-insider, anti-government attitude. These were central Candidate Reagan themes.

However, once in office, President Reagan governed with big spending for security, schools and the other Reaganite objectives listed earlier.

This is a typical Republican pattern. For example, compare the second Bush Administration’s election attacks on Clinton’s spending with the reality of Bush’s huge budget increases — far above Clintonian levels.

Democrats: Leftists, Leaders and Special Interests

Having covered the Republican Party, the discussion of the Democratic Party will be more simple.

The three major factions are similar: those seeking power, those wanting to promote liberal ideas, and the extreme fringe. Let’s start with the fringe.

Where Republican “fringies” call for the reduction of government, Democratic extremists want government to fund, fix, regulate and get deeply involved in certain special interests.

And while conservative populists are generally united in wanting government to be reduced across the board, Democratic special interests are many and in constant competition with each other for precious government funds and attention.

While Republican extremists see the government, Democrats and “socialists” as the enemy, Democratic radicals see corporations, big business, Republicans and the House of Representatives (regardless of who is in power) as enemies.

Republican “crazies” distrust a Democratic White House, the FBI, Hollywood, the Federal Reserve, Europe, the media and the Supreme Court.

Democratic “crazies” hate Republican presidents, the CIA, Wall Street, Rush Limbaugh, hick towns, gun manufacturers, Fox News and evangelical activists.

Republican extremists like talk show hosts and Democratic extremists like trial lawyers.

How’s that for stereotyping?

A Rainbow Fringe

The Republican populist group is one faction — the anti-government faction. Radical Democrats are a conglomerate of many groups — from “-isms” like feminism and environmentalism to ethnic empowerment groups and dozens of other special interests, large and small, seeking the increased support and advocacy of government.

One thing Democrat extremists generally agree on is that the rich and especially the super-rich must be convinced to solve most of the world’s problems.

Ralph Nader, for example, argues that this must be done using the power of the super-rich to do what government hasn’t been able to accomplish: drastically reduce the power of big corporations.

Because Democrats are currently in power, the extreme factions have a lot less influence within the party than they did during the Bush years — or than Republican extremists do under Obama.

The call for a “big tent” is a temporary utilitarian tactic to gain power when a party is in the minority. When a party is in power, its two big factions run the show.

Call the two largest factions the “Governance” faction and the “Politicize” faction.

For Democrats, the Politicize faction is interested in maintaining national security while trying to reroute resources from defense to other priorities; increasing the popularity of the U.S. in the eyes of the world and especially Europe; promoting a general sense of increasing social justice, racial and gender equality, improved environmental and energy policy; and improving the economy.

A major weakness of this faction is its tendency toward elitism and self-righteous arrogance.

Is That Asking Too Much?

The Governance faction has to do something nobody else — the other Democrat factions, the Republican factions, the Independents — is required to accomplish. It has to bring to pass the following:

- Keep America safe from foreign and terrorist attacks

- Pass a health care bill that convinces Independents of real reform within the bounds of fiscal responsibility

- Bring the unemployment rate down — preferably below 7% within the next year

- Keep the economy from tanking

Capturing The Middle Ground

If the Democratic Governance faction accomplishes these four, it will achieve both its short-term governance and its political goals. If it fails in any of them, it will lose much of its Independent support.

The Obama Administration will maintain its base of Democrat support basically no matter what. And the Republican base will remain in opposition regardless.

But without the support of Independents, the White House will see reduced influence in Congress and the 2010 elections.

And when Democrats create scandals like Clinton’s handling of his affairs or the Obama Administration’s “war on Fox News,” Independents see them as Nixonian, responding by distancing themselves both philosophically and in the voting booth.

Independents are powerfully swayed by “The Leadership Thing,” and Obama clearly has it (as did both Reagan and Clinton — but not Bush, Dole, Bush, Gore, Kerry or McCain). It is doubtful that Candidate Obama will lose in 2012.

But “The Leadership Thing” runs in candidates only — not parties.

Obama won because so many independents supported him. Independents are a separate faction that truly belong to neither party.

Indeed, President Obama united most Democrats to support health care reform — partly by taking on Republicans. If a reform bill takes effect, he will likely win the support of Independents by taking on his own party on a few issues and playing back to the middle.

This is power politics.

The 7th Faction: Independents and Independence

Who are these people that vacillate between the parties? Are they wishy-washy, never-satisfied uber-idealist pessimists? Are they the weakest among us?

Why don’t they just pick a party and show some loyalty, some commitment, like Steelers fans or staunch religionists?

Actually, independents are the most consistent voters in America. True, they fluctuate between parties and seldom cast a straight party ballot, but they vote for the same things in nearly all elections.

In contrast, party loyalists stick with their party even when it adopts policies they patently disagree with. Some might argue that this is a more “wishy-washy” way to approach citizenship and voting.

Independents watch the issues, candidates and government officials very closely, since they don’t rely on party platforms to define their values or on affiliations to bestow their trust.

What They Want

Independents want strong national security, open and effective diplomacy, good schools, policies that benefit small businesses and families, social/racial/gender equality, and just and efficient law enforcement.

They see a positive role for government in all these, and dislike the right-wing claim that any government involvement in them is socialistic.

For example: Taxing the middle class to bail out the upper-middle class (bankers, auto-makers, etc.) is not socialism; it’s aristocracy.

Independents are unconvinced by Republican arguments that government should give special benefits to large corporations, or Democratic desires to involve government in many arenas beyond the basics.

Independents care about the environment, privacy, parental rights, reducing racial and religious bigotry, and improving government policy on immigration and other issues.

A Tough Sell

On two big issues, health care and taxation, Independents side with neither Democrats nor Republicans.

They want good health care laws that favor neither Wall Street corporations (a la Republican plans) nor Washington regulators (e.g. Democratic proposals). They want health care regulations that are truly designed to benefit small businesses and families in order to spur increased prosperity.

Independents want government to be strong and effective in serving society in ways best suited to the state, but they expect it to do so wisely and with consistent fiscal responsibility.

They tend to see Republicans as over-spenders on international interventions that fail to improve America’s security, and Democrats as wasteful on domestic programs that fail to deliver desired outcomes.

They want government to spend money on programs that work and truly improve the nation and the world. They are often seen as moderates because they reject both the right-wing argument against constructive and effective government action and leftist faith in more government programs regardless of results.

They want to cut programs that don’t work, support the ones that do, and adopt additional initiatives that show promise.

American Independents & American Independence

The future of America, and American Independence, will be determined by Independents.

Interestingly, Independents come from all six of the factions mentioned in this article. The one thing they all have in common is that they don’t see themselves as part of a specific party, but rather as independent citizens and voters.

The technologies of the past twenty years have made things more difficult for politicians, but they have made it easier for citizens to stand up for freedom.

What we do with this increase in our potential power remains to be seen.

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is the founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

He is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Aristocracy &Featured &Government &Independents &Liberty &Politics &Prosperity