SPECIAL REPORT Part II: Who I Want for President

September 15th, 2014 // 10:34 am @ Oliver DeMille

Diverging Paths

The good news is that the 2016 presidential election has the power to put America back on the right track.

The bad news is that same election could make things a whole lot worse for us.

If the United States votes for eight more years of a White House philosophy that believes in more big government, 2016 will be the year we officially endorsed the decline of America.

In a recent article I suggested that Rand Paul or Mitt Romney have a real chance in the next election. I received a lot of responses to this article—more than usual.

Some of them agreed, others showed support for these or different candidates (Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, Rick Perry, Paul Ryan, Chris Christie, Mike Huckabee, etc.), and still others suggested that the Democratic party is our best hope.

In all this, nobody addressed my main point. It went something like this:

“Wouldn’t it be nice if we elected a president who actually believed in following the letter of the Constitution? How refreshing! What a great boost that would be for freedom—in the U.S. and around the world.”

Freedom President

I suggested that Rand Paul would likely be that kind of leader, and I’m convinced that Mike Huckabee, Mike Lee, and perhaps others would fit this mold.

Think about it! What a powerful concept: A president who reads the Constitution and simply follows it. Now that’s a truly great idea.

The problem is that presidents don’t do this anymore. Worse, the American people don’t even expect them to do it.

The truth is that most recent presidents would tell you they did follow the Constitution, but when they say this they’re talking about the Supreme Court’s definition of the Constitution. That’s not what I mean.

I’m referring to following the Constitution the way the American founders used the phrase: by reading what it says, and following it. Not by using Supreme Court rulings or Attorney General letters as excuses or grants of executive authority.

This is a really big deal. If we don’t read the document and just follow it,* we aren’t really benefiting from what the Constitution is all about.

And freedom will continue to decline.

Contrast Politics

For example, when President Obama announced major airstrikes against ISIS in Iraq and Syria, he made sure to point out that he had the authority to order such military operations without any vote from Congress.

He called this following the Constitution, but it isn’t. The document is very clear: only Congress can vote for long-term military operations.

The president can act to stop a direct, immediate threat to the U.S. homeland, but anything beyond that requires a decision by Congress.

In contrast to Obama’s words, when Rand Paul was asked if the president needed Congressional authority for his long-term military plan, he responded that yes, this is exactly what the Constitution says.

It was refreshing to hear a top potential presidential candidate refer to the authority of the Constitution instead of the interpretations of the Court.

Sadly, Americans aren’t accustomed to hearing such words. Politicians refer to past precedents, the War Powers Act, Supreme Court decisions, earlier Congressional approvals that could be interpreted to apply in the current situation, and other policies—and all these distract from the real point.

The framers wrote the Constitution so the regular people could read and tell—with no help from experts—when their government officials were following it and when they weren’t.

False Authority and Failing Checks

It has become commonplace for the White House to simply ignore the Constitution, to intervene when and where it chooses, without regard to the document, and to claim that the Court gave it such power or that Congress allowed it such powers.

But the Constitution doesn’t give the Court or Congress the authority to grant the executive any powers. The Court can check the Oval Office, as can Congress, but neither have the Constitutional power give the Executive additional authority.

The people, not the Court, are the final experts on the Constitution. Presidents routinely pay little heed to the Constitution because the people let them get away with it.

The people keep electing candidates who openly say the role of the president is to go beyond the Constitution—especially in foreign relations, but also in domestic policy. As long as we keep voting this way, we keep losing more freedom.

Recent presidents from both parties have egregiously ignored the Constitution. And among the current potential candidates for president, it is commonplace to speak of following the Constitution and mean the modern, Beltway view of the president’s powers—ignoring the actual words in the document itself.

That’s why I’m so impressed when I hear Rand Paul and Mike Huckabee talk in a totally different way. Or Mike Lee, though he’s shown no interest in the 2016 presidency.

Again, wouldn’t it be great to elect a president who doesn’t consult Washington insiders but rather the pages of the U.S. Constitution when an issue arises.

Imagine a president who would tell Congress that we need serious military action but he won’t take it without their approving vote.

That kind of leadership is sorely missing in America, and one of the top causes of our decline.

Keepers Above the Law

One root of the problem is that most Americans today don’t really believe in limits on government. For example, just watch how the police behave in almost every cop-oriented television drama and movie.

They frequently don’t wait for a warrant, they smash in doors of homes and apartments with guns waiving and SWAT units swarming. The good cops, the best officers in these shows, are the ones who push the law to its furthest limits and even break it when they deem it “necessary.”

The more they ignore or circumvent the Constitutional guidelines and get away with it, the better cops they are. Or so they are portrayed.

I’m not saying that the Hollywood version of police actions is always accurate in real life (though the increased militarization of law enforcement is a serious, growing threat to regular citizens).

I am saying that these TV dramas and movies are a very real portrayal of how most Americans believe the cops are and should be.

This is what our culture has come to consider good police work—finding ways to sneak around or get away with just ignoring Constitutional limits, protections, and due process.

Vice as Virtue

Most Americans won’t say it in so many words, but they are used to thinking of police officers as above the law in many—if not most—situations, and of expecting the good cops to bend the “annoying” Constitutional limits and just do whatever is needed to go get the bad guys.

And if this is how they see the police, consider how much more they admire this same bravado in the President.

Of course, both parties whine when a president from the other party exerts unconstitutional influence or executive orders to expand his power. But they frequently defend their own party’s president in the same, or worse, abuses.

It’s literally endemic in our modern system. It bears repeating until we realize what a major threat this is!

The way our majority culture now sees it, the best cops and government leaders do whatever it takes, even bending or ignoring the Constitutional rules, to “do the right thing.”

The way our majority culture now sees it, the best cops and government leaders do whatever it takes, even bending or ignoring the Constitutional rules, to “do the right thing.”

Think of the most popular police dramas and movies—the main character(s) is always the “good guy” who breaks the Constitutional boundaries in service of the greater good.

NCIS, CSI, Blue Bloods, Hawaii Five-0, Law and Order, Chicago PD, Arrow, Bones, Castle, Criminal Minds, NCIS Los Angeles, Agents of SHIELD, Scandal, Covert Affairs, 24, The Blacklist, and many others, all follow this plotline.

These aren’t obscure programs; they are among the most popular in our era. One or more of them is almost always playing on American prime time, and our culture is inundated with their messages.

The Power of 2016

This is how we see government officials, and especially the government agents who carry guns or work in the Oval Office. Again, I’m not saying people openly support this view in polls; I’m saying it is now part of our gut-level cultural expectation.

A majority of Americans now think government agents can and even should routinely push and even break Constitutional limits.

Yes, some people watch cop shows or government dramas and think, “That’s terrible! How can our leaders consistently get away with just disregarding and even flouting the Constitution? They should be reprimanded and removed.” But such Americans are a small minority.

Most of the electorate considers such behavior by police and top executive officials as the norm, and as what is needed to get the job done.

When someone they personally know or identify with gets pushed around, they cry unfair. But when it’s just other people suffering at the hands of abusive government actions, most voters turn a blind eye.

Would I like something different, a president who reads the Constitution to see if he has the authority for a certain action and then realizes he doesn’t and chooses to stay within the bounds of that great document? You bet I would. The future of freedom depends on it.

The thing is, I think we actually have the power to elect such a leader in 2016. Watch what the potential candidates say. So far, Rand Paul and Mike Huckabee are excellent examples of leaders who talk a lot about following the Constitution and really stand for this approach. Regardless of political parties, that’s the kind of President we want.

* Of course, the people have made changes to it over time, including the Amendments and the end of slavery and reduction of racism (there is more work to be done on this). Note that these changes were made by the people, not the federal government, and following them is in keeping with the people overseeing their leaders and holding them to the Constitution.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Among many other works, he is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, The Coming Aristocracy, and FreedomShift: 3 Choices to Reclaim America’s Destiny.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Government &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Politics &Statesmanship

Are You Part of TV World (A Different Way to Get the News)

March 21st, 2014 // 12:01 pm @ Oliver DeMille

Where to Look

I keep getting asked what I read to study current events. I actually taught a whole class on this recently—and it’s still available. By taking this class, you’ll get the real scoop on the best current events publications.

In this article, I’ll just share the Cliff’s Notes version. Read Foreign Affairs, the Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, and The Economist.

There. That’s it.

Enjoy.

But there is a deeper way to think about this. To begin, there is actually a bit of a problem with the question itself: “What should I read to study current events?” The real answer is, “Everything.” Read a lot. If you’re conservative, read conservative and liberal publications. If you’re liberal, read liberal and conservative periodicals. You can’t study current events from one political view—not if you want to really know what’s happening.

Compare and Contrast

This goes for television and radio as well. When I watch a certain event to see how it is reported in the news, I always see what MSNBC and Fox News both have to say. Then I watch CNN and one of the networks, usually ABC or CBS, for their views as well. Bloomberg Television, C-Span, and PBS news shows often add interesting nuances.

But reading is better than watching. The NY Times and Wall Street Journal are fun to compare. USA Today and various online thought leaders share vital out-of-the-box insights. I could go on and on. Read. Read a lot. Read more.

But that’s only half of the message. The other half is a bit counter-intuitive, but it is still very important.

One of the problems with looking for one or two publications to read is that it limits us to one or two publications. This brings us to the main point: It is a major problem when we only get our news from news outlets.

To really know what’s going on in our world, you have to get beyond the news. Behind the news, under the news. You have to feel what the people are feeling, and dig to get a sense of what is happening in their culture. Their daily lives.

Culture and Events

To do this, I read lots of non-news publications. They are incredibly insightful. I read men’s magazines (like Men’s Health, Esquire, GQ, etc.), women’s magazines (Vanity Fair, More, Good Housekeeping, etc.), variety magazines (Rolling Stone, Entertainment Weekly, Via), cultural magazines (The Atlantic, Foreign Policy, Harper’s, etc.), specialty magazines (Harvard Business Review, Guns and Ammo, Yoga Journal, etc.), science magazines (Psychology Today, Prevention, Popular Science, etc.), and more. These teach as much about current events as any news publication.

For example, I like to go to Barnes and Noble and grab a copy of Yoga Journal, Guns and Ammo, Entertainment Weekly, and Harvard Business Review. Then I read the main articles in each, in one sitting. It’s fascinating. These four publications are written to very different audiences, as you might have gathered, and they use different vocabularies, examples, assumptions, and writing styles. Yet all are quality publications with important articles. Add TV Guide to these four and you’ve got a manual on current America—like it or not.

Together they give the reader a cross-section insight into current events, much more than you could get by concurrently reading a top conservative magazine (say, The Weekly Standard) and liberal periodical (for example, The Nation). The ads in each of these four magazines listed above teach almost as much, sometimes more, than the articles. Reading non-news publications along with news is the key to really understanding current events.

Take off the Rose Glasses

Really. It is important, however, to read them differently than typical readers. Don’t read non-news periodicals looking for literal news. Read them to see what things they talk about that are newsworthy. Read like an anthropologist, looking for interesting trends and groups in modern society that could influence the world.

And think, think deeply, while you read. What does each article say (implicitly as well as explicitly) about our modern society? What trends does it portend? What assumptions does each author make about our current world, and what does this tell you about our culture?

Become a voracious reader. Turn TV World into Thinking World, at least in your own life. Oh, and ask the same kinds of questions when/if you watch television. We live in an Information Age, but we need more people who treat it like a Thinking Age.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Among many other works, he is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, The Coming Aristocracy, and FreedomShift: 3 Choices to Reclaim America’s Destiny.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Blog &Culture &Current Events &Education &Generations &Information Age &Statesmanship

What is Freedom?

June 17th, 2013 // 10:38 am @ Oliver DeMille

I frequently get asked something along the lines of, “Oliver, you talk a lot about freedom; but what, exactly, do you mean by the word ‘freedom?’ How do you define it?”

It’s a very good question. To answer it, I first want to define “liberty.” After all, the Declaration of Independence boldly affirms that among our inalienable rights are “…life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Actually, the key word in this sentence is “inalienable,” and everyone should read the excellent article by Kyle Roberts on what this word really means.

Liberty and freedom are similar, but they are slightly distinct, and understanding them both is essential in a society that is losing its freedoms.

Liberty

As for “liberty,” I define it as “the right to do whatever a person wants as long as it doesn’t violate the inalienable rights of anyone else.” Of course, in order to exercise liberty, a person needs to know what inalienable rights are—otherwise, he won’t know whether or not he is violating them.

Thus knowledge and wisdom are required to maintain one’s liberty, because a person who violates somebody else’s inalienable rights naturally forfeits his own liberty. The extent of this forfeiture is equivalent to the depth of the violation—when this is applied well, it is called justice.

License

License, as opposed to liberty, is defined as “the prerogative to do whatever a person wants or is able to do.” Note that this has often been used in history as an excuse to plunder, force or otherwise violate the rights of others. Thus license and tyranny are nearly always connected—the tyrant is tyrannical precisely because he takes license as he wills, and the person who pursues license eventually exerts tyranny of some kind.

Sometimes people pick one of the inalienable rights and use it to define “liberty,” such as: “Liberty is the right to do whatever a person wants as long as it doesn’t violate the property of another. Or … the life of another, etc. The problem with this type of definition is that though it is often accurate, it is also too limited. The violation of any inalienable right takes away one’s liberty.

Now that we have a definition of “liberty,” we can also define and compare the meaning of “freedom”:

Liberty: The right to do whatever a person wants as long as it doesn’t violate the inalienable rights of anyone else.

Freedom: A societal arrangement that guarantees the right of each person to do whatever he/she wants as long as it doesn’t violate the inalienable rights of anyone else.

“Liberty” comes from the Latin root liber though the French liberte, meaning “free will, freedom to do as one chooses … absence of restraint” (Online Etymology Dictionary). In contrast, the word “freedom” was rooted in the Old English freodom, which meant “state of free will; charter, emancipation, deliverance” (ibid). Thus liberty could exist with or also without government, but freedom was usually a widespread societal system that required some authority to maintain it.

In most eras of history, the goal is liberty, but it is almost never maintained without freedom. In other words, it is possible to have liberty without freedom, but in such cases it seldom lasts very long and it is usually only enjoyed by a limited few.

When freedom is present, however, liberty exists for all who don’t violate the inalienable rights of others.

What About Now?

This trip down memory lane has an important current application. A lot of people want liberty; in fact, nearly everyone desires liberty. But the only duty of liberty is to honor the inalienable rights of everyone else, and as a result liberty without freedom is fleeting.

In contrast, freedom requires many more duties, and therefore it musters much more from its people. It only succeeds when the large majority of people in a society voluntarily fulfill many duties that keep the whole civilization free.

To repeat: those who stand for freedom must honor the inalienable rights of all, and they must also take responsibility for standing up and helping ensure that society succeeds. No truly free government directs this free and voluntary behavior, but without it freedom decreases.

For example, one of the duties of those who support freedom is free enterprise—to take action that improves the society and makes it better. No government should penalize a person who does not do this (such penalties would reduce freedom), but overall freedom will decrease if a person has the potential to take great enterprises that improve the world, but doesn’t.

Thus freedom is very demanding. If people don’t voluntarily do good things, and great things, freedom declines. If they don’t exert their will and take risks to improve the world, freedom stagnates and decreases.

Freedom and Morality

Another way that people voluntarily increase freedom is by choosing morality. In societies where a lot of the people don’t choose a moral life, liberty may be maintained by some people but the freedom of all people eventually declines. When more people choose the path of virtuous living, freedom grows.

The same is true of charity and service. When more people choose it, freedom increases. There are a number of other ways people can voluntarily take actions that have a direct and positive impact on freedom. In the freest societies, a lot of the people choose to engage in many such behaviors.

When we pledge allegiance to the flag, we do so to promote “…liberty and justice for all.” This is the role of government—liberty and justice, or in other words the protection of inalienable rights and the providing of recompense if such rights are violated.

But while in free nations government is limited to this role, the people in a free society must do much more. If they all do their best, fully living up to their potential, freedom greatly increases.

In other words, the real question isn’t “What is freedom?” but rather “What is my role in freedom?”

The answer is different for each person, but the key is to not worry about how other people use their freedom. As long as they aren’t violating inalienable rights, they won’t hurt you. Your focus (and my focus, and each individual’s focus) should be, simply, “Am I living up to my full potential, my great life mission and purpose in this world?”

If your answer to this question is “yes,” you are a promoter of freedom and your efforts and projects will help increase freedom for everyone. If not, now is the time to get started…

Category : event &Featured &Foreign Affairs &Information Age &Liberty &Mini-Factories &Mission &Politics &Statesmanship &Technology &Tribes

Attention Span: Our National Education Crisis

September 22nd, 2011 // 10:04 am @ Oliver DeMille

This article was originally published as a newsletter article for Oliver’s college students, and was later featured as a chapter in the book A Thomas Jefferson Education Home Companion.

This article was originally published as a newsletter article for Oliver’s college students, and was later featured as a chapter in the book A Thomas Jefferson Education Home Companion.

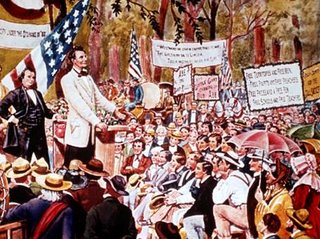

On October 16, 1854, in Peoria, Illinois, Stephen Douglas finished his 3-hour address and sat down. Abraham Lincoln stood.

He “reminded the audience that it was already 5 pm,” and then told them that it would take him at least as long as Mr. Douglas to refute his speech point by point, and that Mr. Douglas would require at least an hour of rebuttal [1].

He recommended that everyone take a one-hour dinner break, and then return for the four additional hours of lecture. The audience amiably agreed, and matters proceeded as Lincoln had outlined.

“What kind of audience was this? Who were these people who could so cheerfully accommodate themselves to seven hours of oratory?”[2]

This was only one of seven debates, and many people attended as many as they could.

In contrast, I was invited as a guest on the early morning NBC station newscast in Yuma, Arizona the day after the Columbine High School tragedy in Littleton, Colorado. The primary purpose of my visit was to deliver lectures at the local community college and then give a speech at an annual foundation banquet—the title of my speech was along the lines of “What Jefferson Would Do to Fix Modern Problems.”

The Columbine coverage took up most of the hour, and when it came time for our interview the anchor turned to me and said, without any preview, something like: “What would Thomas Jefferson think about this Columbine tragedy—you have 30 seconds.”

I don’t remember my exact answer, but I tried to communicate that Thomas Jefferson would not try to analyze and solve such a problem in thirty seconds, and until our means of dealing with serious national problems stops being handled in 30-second sound bite opinions we will continue to see such problems—indeed, they will get worse.

With that our interview was over, we unhooked our microphones and left the studio.

But the event has troubled me ever since. Hundreds of television professionals asked similar questions over the next few days, and have done so repeatedly with hundreds of events since—answers are given in thirty second sound bites, people shake their head at the day’s latest shocking news, and then they go on about their work.

This is how we deal with problems in America today—and then we conclude by calling on government to fix everything. We express opinions–in soundbites on television, at work and social events, and in restaurants and taxis. Then we shake our heads and go back to our lives. We live on a steady diet of opinions, opinions, opinions. In 30-second doses. And then we forget and move on.

What is the difference between these two audiences—those who listened attentively for seven hours to Lincoln and Douglas and came back for more, and those of us who hear and express opinions lightly and then move on?

Not to put too fine a point on it, but these two audiences are drastically different—in their culture, their education, their habits and in their capacity to be free.

The group who heard Lincoln were capable of education, and capable of freedom. The latter group is largely incapable of either unless something changes.

Specifically, a great education ultimately comes down to one thing. Those who have it can gain a superb education. Those who don’t cannot. A nation of people with it can earn its freedom. A nation without it is either not free or in the process of losing its freedom.

If you are going to be a successful leader in the future, you must develop this trait. It is not just a nice thing to have, or a good thing—it is essential; it is vital.

Without it you cannot be a statesman and the world will be led by whoever has it—whether they are virtuous or not, good or evil, dedicated to moving the cause of liberty or some other cause.

You will probably not like to hear what I have to say about it—because it will mean that you have to change, and change is hard; I didn’t like it when I learned it–because I had to change.

Jefferson probably didn’t like it either, but he did it. Lincoln probably didn’t like it; but he did it. You must have this trait if you want to be a successful learner and become a leader. The nation must have leaders with this trait if it is to stay free.

So, if I say things you don’t like, ignore that. Don’t ask, “Do I like what he’s saying?” Ask, “is it true? And what changes will I make because it’s true?”

Each of us needs this trait because each of us wants to fulfill our mission in life, to really make a difference in the world. So, even if it is hard to get this trait–and it is–it is worth it, and it is important.

The vital trait I speak of is attention span.

II. Attention Span and Freedom

Of course, attention span by itself is not enough to guarantee education or freedom, but a person lacking attention span must either develop it or he will not become educated, and a nation without attention span must either gain it or lose its freedoms.

If I were speaking of making money, the point would be obvious. If you don’t go to work and stay a few hours, your paycheck will be small.

In fact, figure out what your paycheck would be if you crammed your work the day before a big bill was due, and you’ll have a pretty good indication of how much that same amount of study is really worth.

Or, figure out how much money you’d make if you spent four years putting in an hour or two a day between fun activities—you certainly wouldn’t make enough to live on.

If you put in that same kind of study, you won’t have much of an education to show for it either. The diploma on the wall may look the same, but it will be empty of meaning.

Without attention span—specific, dedicated time spent at work or managing one’s resources—income and wealth will dry up. The same is true of education, where the currency is study instead of labor, and the commodities are virtue, wisdom and freedom.

But how does a person or nation without attention span develop it, increase it, or improve it? There is only one way: discipline yourself to put in the time.

Speaking of attention span and education: Slow down and learn. Slow down and put in the time reading, writing, discussing, listening, pondering, thinking, praying. Spend hours and hours in the classics, and you will acquire a superb education. A nation of superbly educated individuals will maintain its freedom.

In Lincoln’s day the culture of learning was based around books. Today, as Neil Postman points out in his excellent book Amusing Ourselves to Death, the culture of learning is based on television and internet technology.

All of our forms of public discourse are based less and less on books and more and more on electronic media.

Most of the major decisions of society are made in five places—families, churches, schools, businesses and governments—and four of the five are moving consistently away from books toward electronic media.

Politics is now almost exclusively an electronic event, more and more people attend church in front of their television set, businesses survive through electronic marking, and schools are “computerizing” as quickly as possible—the wave of the future, we are told, is virtual education, virtual politics, e-business and electronic evangelizing.

Even the family is increasingly virtual—parents and children communicate with fax and email, and family time is increasingly spent in front of the television set, except for those off in their own rooms surfing the net.

Now don’t get me wrong: I like the latest hit movie or website as much as anyone, and I believe that television and internet technology are of great benefit to society—they significantly empower business and greatly enhance entertainment.

But they have also displaced books as the source of cultural learning, and this is a very discouraging development because of the impact of society’s morals; but that is not my chief point here.

My point is that it is bad to replace books with television and internet because of the consequences to education and freedom.

Specifically, the medium of the electronic screen teaches at least five deadly fallacies about education, and consequently freedom:

Fallacy Number 1: Learning should be fun.

Indeed, the lesson seems to be that everything should be fun.

The worst criticism of our time is that something is boring, as if that made it less true or less important or less right.

There is nothing wrong with fun, but there is everything wrong with a society whose primary purpose is to seek fun.

In American society, particularly among those under 40, the love of fun is the root of all evil. This is the legacy of the sixties—seeking fun has become a national pastime.

With respect to the education of an adult, fun is simply not a legitimate measurement of value.

Things should be judged by whether or not they are good, true, wholesome, important or right. Commercialistic society judges things by whether they are profitable, and even socialism judges whether something is fair or equitable.

But what kind of a society makes “fun” the major criteria for its actions and choices?

Consider how this lesson impacts the education of youth and adults. Learning occurs when students study. Period. No fancy buildings or curricula or assemblies or higher teacher salaries change this core principle.

Learning occurs when students study, and any educational system is only as good as the student’s attention span and the quality of the materials.

Now, study can be fun, but it is mostly just plain old-fashioned hard work, and nearly all of the fun of studying comes after the work is completed.

In essence, there are really two kinds of fun—the kind we earn (which used to be called “leisure”), and the kind that we just sit through as it happens to us (entertainment). There are very few things in life as fun as real learning, but we must earn it. And this kind of fun always comes after the hard work is completed.

No nation that believes that learning should be fun, in the unearned sense, is likely to do much hard studying, so not much learning will occur.

And without that learning the nation will not remain free. Nor will people stay moral, since righteousness is hard work and just doesn’t seem nearly as fun as some of the alternatives.

No nation focused on unearned fun will pay the price to fight a revolutionary war for their freedoms, or cross the plains and build a new nation, or sacrifice to free the slaves or rescue Europe from Hitler, or put a man on the moon. We got where we are because we did a lot of things that weren’t fun.

Americans today believe that it is their right to have fun. Every day they expect to do something fun, and they expect nearly everything they do to be fun. Most adults eventually figure out that fun isn’t the goal, but many of today’s students firmly believe that learning must be fun; if not, they put down the books and go find something else to do.

Fallacy Number 2: Good teaching is entertaining.

Since fun is the goal, teachers must be entertaining or they aren’t good teachers. “He is boring,” is the worst criticism of a teacher these days.

The problem with this false lesson, besides the fact that some of the best teachers aren’t a bit entertaining, is that it assumes that teachers are responsible for education in the first place.

Now remember, I’m speaking of the role of adult and youth students to own their responsibility for their education.

This is not intended as license for parents and educators to abdicate the responsibility to be all that they can be as mentors.

But think of it: if we, as students, are waiting around for our teachers to get it right or else we’re not gonna study, who really loses?

Whose job is education anyway?

All of us have watched a movie with a bad ending, and since our goal in watching was to be entertained, we are upset that the movie ended that way. We blame it on whoever made the movie; it was their fault.

Our culture approaches teachers the same way—if we weren’t entertained or didn’t learn, it is their fault. “What kind of a teacher is he, anyway; I didn’t learn anything in his class.”

But if I don’t learn something in a class, it is my own fault, no matter how good or bad the teacher is.

Good teaching is a wonderful and extremely important commodity, but that is another essay, and it is not responsible for a student’s success. Students are. To tell them otherwise is to leave them victims who are forever at the mercy of the system.

And history is full of examples of students who owned their role and achieved greatness because they recognized that it was their job to supply the motivation and the effort to gain a great education.

Our society likes to blame its educational shallowness on its teachers because it is just plain easier to blame than to study. And it is easier for parents and politicians to join the blaming game than to set an example of studying that will inspire their youth to action.

The impact on education is clear: We blame teachers and our schools for the problems, while we do everything except the hard work of gaining an education for ourselves, thus inspiring and facilitating our children to do the same.

The impact on freedom is equally direct: Students who have been raised to blame educational failure on someone else usually become adults who expect outside experts to take care of our freedom for us.

Even those who become activists tend to spend a lot of time exposing the actions of others, “waking people up” to what “they” are doing.

And whether “they” refers to conspirators, liberals, or the religious right, the activists seldom do anything about the situation except talk—in more shallow 30-second sound bite opinions.

A corollary of this false lesson is that students need a commercial every 8.2 minutes. We are conditioned to short attention spans, and therefore to shallow educations and nominal freedoms.

The reality is that unless you spend at least two hours on something, chances are you didn’t learn much. Without attention span, little is learned.

Fallacy Number 3: Books, texts and materials should be simple and understandable.

Now, mind you–I’m not suggesting that authors should be purposely obscure or irrelevant. I’m just returning to the idea that we, as students, must step up to whatever obstacles may be in our way.

It’s our job to do whatever it takes to get an education, no matter the quality or interest level of our materials. But even beyond that obvious point, the problem with this error is that the complex stuff is actually the best, the most interesting, ironically the most fun, and certainly the most likely to produce individual thinkers and a free nation.

The classics, the scriptures, Shakespeare, Newton—works really worth tackling are the best and most enjoyable.

Consider the impact of simple materials on education. For example, what kind of nation would the founders have framed had they been taught a diet of easy textbooks, easier workbooks, more quickly understood concepts and curricula?

A free people is a thinking people, and thinking is hard work—it is, in fact, the hardest work, which is why so little of it takes place in a society which avoids pressure and takes the easy path.

The only reason to choose easier curriculum is that it is easier, but the result is weaker graduates, flimsier characters, vaguer convictions and impotent wills.

Thucydides said it bluntly: “The ones who come out on top are the ones who have been trained in the hardest school.”

This is true of individuals and of nations.

I am not saying that everything that is hard has value, but I am saying that most things of value are hard. If your studies weren’t hard, really hard, chances are you didn’t learn much.

Fallacy Number 4: “Balance” means balancing work with entertainment.

Today’s adults don’t usually find out what really hard work is until they graduate and have to support a family. The average person supporting a family in modern America puts in over fifty hours a week at work; in most countries the amount is much higher.

But the American high school system conditions most students to attend class five hours a day and do outside study a few extra hours a week. The rest of the time is filled with activities, friends and occasional family time. And this has become the standard for balance.

Most college students follow suit: they are in class three to five hours a day, they study a couple of hours a day, and they fill the rest of the time with activities and friends.

Again, this is considered “balanced.”

Once people get out of school and go to work, “balance” most often means the need to spend more time with their family.

But while in school, they say it to mean that they need to spend more time with their friends engaging in fun activities. Family time and study time are shoved aside.

One of my mentors, a religious leader from my faith, taught that the right approach to daily life is eight hours a day of sleep, eight hours a day of work, and eight hours a day of leisure.

And he spoke at a time when leisure didn’t mean entertainment.

Indeed, leisure means serving people, studying, learning, being involved in community service and government, and so on—whereas the slaves in Rome were considered incapable of leisure and so their masters gave them entertainment to keep them pacified.

The media age has tried to convince us all, quite successfully, that we need entertainment—and often.

I take the eight hours sleep, eight leisure and eight work quite literally—it is a solid and realistic approach to “balance.”

In all my years of teaching, I have never had a married, working 40 hours a week student complain about not having time to study. They all make the time.

Those who complain are always those wanting more time for entertainment, never those who want more time for work or family.

Every single one of those complaining that they want balance has been someone without a full or steady part time job. That is amazing to me.

The simple truth is that they are right—they do need balance. They need to start working and studying as if they were college students.

Studying a minimum, and I mean minimum, of forty hours a week in college is balance—it balances the pre-college years where most students did real, intensive study only a few hours in their whole life.

And a few college students actually studying enough to become Jeffersons and Washingtons is balance to a whole generation of college students playing around.

If you really want to invoke balance, I think you could make a strong argument that entertainment is not part of a balanced life—unless it is the leisure sort done with family or to learn or serve. Get rid of entertainment time, and fill it with studying, and you will start to find balance.

Until then, you will continue to feel unbalanced—and whatever you blame it on, the study will not unbalance you.

On occasion I have had students who did become unbalanced in the side of their studies, and I have recommended that they cut back and spend more family time. But this has happened perhaps three times out of hundreds of students.

In contrast, it always surprises me who tries to argue for balance—they are usually the ones in no danger whatsoever of becoming unbalanced studiers.

Fallacy Number 5: Opinions matter.

This is perhaps the biggest, most widespread and most fallacious lesson of the electronic age.

A time traveler visiting from history might well consider this the most amazing thing about our age. Everybody has an opinion, which can be delivered in 30 seconds or less, and these opinions are considered newsworthy, valuable, and a sound basis for public policy and individual action.

But an opinion is really just something you aren’t sure about yet–either because you haven’t done your homework, or because after the homework is thoroughly complete the answers are still a bit unclear.

Opinions are at best educated guesses, at worst dangerously uneducated guesses. In any case, opinions are just guesses.

Great people in history know and choose. Opinions are really nothing more than the lazy man’s counterfeit for knowing and choosing. Again, there is a place for opinion, but after the hard work is completed, not as a replacement for it.

In short—opinion is not a firm basis for anything except passing time (which may be one of the reasons the market won’t listen to more than 30 seconds of it at a time).

Imagine what the educational system might look like in a society that values opinions over knowledge. Or try to imagine the future governmental and moral choices of a society where all opinions are created equal, and endowed by their creator with inalienable rights.

Certainly such a society will not be wise, or moral, or free.

III. How to Increase Attention Span

Now, in pointing out these false lessons of the electronic age, my point is not that books are better than computers or televisions. There is nothing I know of that makes paper and binding inherently better than plastic and silicon.

Computers are better than books for many things, such as tracking and storing large amounts of information, speeding up communication and technological progress, and increasing the efficiency and even effectiveness of business.

Television is better than books for many purposes, including mass and speedy communication, business advertising and marketing, and entertainment options where important ideas can be portrayed and carried to the hearts of people more quickly.

My point is not that books are inherently better than electronic screens, nor is it that electronic media is bad. Nor is my point that the electronic media undermines our morals; the truth is that many books are at least as bad.

My point is that books are better than television, or the internet, or computer for educating and maintaining freedom.

Books matter because they state ideas and then attempt to thoroughly prove them.

The ideas in books matter because time is taken to establish truth, and because the reader must take the time to consider each idea and either accept it, or (if he rejects it) to think through sound reasons for doing so.

A nation of people who write and read is a nation with the attention span to earn an education and a free society if they choose.

The very medium of writing and reading encourages and requires an attention span adequate to deal with important questions and draw sound and effective conclusions. The electronic media arguably does not do this in the same way.

Now, idealism aside, the reality is that 30 second sound bites is how public dialogue takes place in our society, and we can either whine about it or we can adapt to the realities and develop our skills to be leaders.

A leader of public dialogue in our day must use the 30 second method; in fact, the reality is closer to 6 seconds than 30.

I am not saying that we should ignore this reality and prepare for 7-hour debates to impact public opinion. The electronic age is real and statesmen should be prepared to utilize it effectively.

But there is a huge difference between those who just polish their media technique and those who do so after (or at minimum, while) acquiring a quality liberal arts education.

Technology is a valuable tool, and a person who has paid the price to know true principles and understand the world from a depth and breadth of knowledge and wisdom, and then applies his or her wisdom through technology is much more likely to achieve statesmanlike impact.

His 6-second sound bites will not be opinions, but rather ideas that have been fully considered, weighed and chosen.

Indeed, and this is my most important point, in the electronic age your attention span is even more important than it was at other times in history.

The future of freedom may well hinge on one thing—our attention spans. And certainly your future success as a leader and statesman depends on your attention span.

One thing is certain: there will be no Lincolns, Washingtons, Churchills, Gandhis, or the mothers and fathers who taught them, without adequate attention span.

CONCLUSION

I wish I had some tricks to give you to increase your attention span. But there is only one that I know of: discipline and hard work, hours and hours and hours studying, with hopefully some prayer and meditation in the mix.

There will be leaders of the next 50 years; I believe you will be among them. But only if you increase attention span.

Otherwise, you will be one of the masses, going along with whatever those in power do to society, led along by your “betters”—not because they are better morally, but because they have a longer attention span.

Too many leaders in history have been people without virtue, who ruled because they had the knowledge. Knowledge truly is power. In this day, it is time for people of virtue to also become people of wisdom.

I challenge each of you to be one of them.

Don’t let your habits of entertainment, your attachment to fun and slave entertainment stop you from becoming who you were meant to be. Become the leader you were born to be—spend the hours in the library. Let nothing get in your way.

Many things will arise to distract you; study will often seem the least attractive alternative for the evening. But you know better. You were born to be the leaders of the future.

Now do it—not in 30-second sound bites of opinion, but in seven to ten hour daily stretches of building yourself into a leader, a statesman, a man or women capable of doing the mission God has for you.

Endnotes:

- Postman, Neil. 1985. Amusing Ourselves to Death. New York: Penguin Books. p.44

- Ibid.

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, 1,1.84.4. For a fuller treatment of this subject, see Josiah Bunting III. 1998. An Education for Our Time. Washington D.C.: Regnery Publishing, Inc.

Category : Blog &Citizenship &Education &Generations &Government &History &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty

Freedom in Decline and the Missing Metaphor

July 6th, 2011 // 9:40 am @ Oliver DeMille

One reason freedom is threatened with serious decline in our time is that metaphor is often missing among those who love liberty.

Our modern educational system has taught most of us to focus on the literal, to separate the fields of knowledge, to learn topics as if they are fundamentally detached from each other, and to build areas of expertise and career around disconnected specialties.

We are even encouraged to separate the various parts of our life—not only math class from English class or gym from history, but also school from family, work from private lives, spouse from child relationships, family from friend relationships, religion from politics, career from entertainment.

Most children and parents leave home in the morning to spend time at school, work and other separate activities—ultimately spending less time with each other than with people outside the family. Anything less than such separation of the various parts of our lives is considered unhealthy by many experts.

Thus it is not surprising that the use of metaphor is often missed in our modern world. We seem to be a nation of literalists now. We understand allegory, comparison, contrast, simile and even imagery, as long as the comparisons are patently apparent or clearly spelled out. Metaphor?—not so much.

There are many exceptions to this, of course, but such literalism is increasingly the norm. Symbol is and will always be important, but the artistic, understated, abstract and poetic is out of vogue in many circles that promote freedom.

Stay Out of Politics

Consider, for example, the way some conservative radio talk-show hosts rant against Hollywood actors or best-selling singers speaking out on political themes. The argument in such cases usually centers on the idea that actors/performers have no business opining on political topics—that, in fact, they know little about such things and should stick to their areas of expertise.

At one level, this assumes that the actors’ roles as citizens are trumped by their careers. Ironically, such talk-show hosts usually give great credence to the voices of regular citizens as part of their daily fare—as long as the citizens tend to agree with the host. Likewise, such hosts frequently seek credibility by bringing like-minded celebrities to their show. Note that this is a favorite tact of media in general—television as well as radio, liberal as well as conservative.

At another level, the idea that actors or other artists are simply entertainers rather than vitally important social commentators misses the deep reality of the historical role of art. Artists are as important to social-political-economic commentary as journalists, scientists, the professorate, clergymen, economists, the political parties or other public policy professionals.

Napoleon is sometimes credited with saying that if he could control the music or story-telling of the nation he would happily let the rest of the media print what it wanted: “A picture is worth a thousand words.” (Or more literally, “a good sketch is better than a long speech.”)

Those who think artists are, or should be, irrelevant to the Great Conversation might consider such artists as Harriet Beecher Stowe, Nietzsche, Goya, Picasso, Goethe, Ayn Rand, C.S. Lewis or George Orwell. Can one really argue that Ronald Reagan, Charleston Heston, Tina Fey, Jon Stewart, Aaron Sorkin or the writers of Law and Order have had only a minor impact on society and government?

Artists should have a say on governance–first because all citizens should have a say, and second because the fundamental role of the artist is not to entertain (this is a secondary goal) but to use art to comment on society and seek to improve it where possible. The problem with celebrity, some would argue, is that many times the public gives more credence to artists than to others who really do understand an issue better. This is a legitimate argument, but it tends to support media types rather than the citizenry.

Early American Art

On an even deeper level, art is not just the arena of artists. Tocqueville found it interesting that in early America there were few celebrity artists– but that most of the citizens personally took part in artistic endeavors and tended to think artistically.

Another way to say this is that they thought metaphorically in the broad sense:

- They clearly saw the connections between fields of knowledge and the application of ideas in one arena to many others

- They understood the interrelations of disparate ideas without having to literally spell things out

- They immediately applied the stories and lessons of history, art and literature to current challenges

Another major characteristic Tocqueville noted in early American culture was its entrepreneurial spirit, initiative, ingenuity and widespread leadership—especially in the colonial North and West, but not nearly so much in the brutal, aristocratic, slave-culture South of the 1830s.

Freedom and entrepreneurialism are natural allies, as are creative, metaphorical thinking and effective initiative and wise risk-taking.

I’ve already written about the great on-going modern battle between innovation and conformity (“The Clash of Two Cultures”), which could be called metaphorical thinking versus rote literalism:

In far too many cases, we kill the human spirit with rules of bureaucratic conformity and then lament the lack of creativity, innovation, initiative and growth. We are angry with companies which take jobs abroad, but refuse to become the kind of employees that would guarantee their stay. We beg our political leaders to fix things, but don’t take initiative to build enough entrepreneurial solutions that are profitable and impactful.

The future belongs to those who buck these trends. These are the innovators, the entrepreneurs, the creators, what Chris Brady has called the Rascals. We need more of them. Of course, not every innovation works and not every entrepreneur succeeds, but without more of them our society will surely decline. Listening to some politicians in Washington, from both parties, it would appear we are on the verge of a new era of conformity: “Better regulations will fix everything,” they affirm.

The opposite is true. Unless we create and embrace a new era of innovation, we will watch American power decline along with numbers of people employed and the prosperity of our middle and lower classes. So next time your son, daughter, employee or colleague comes to you with an exciting idea or innovation, bite your tongue before you snap them back to conformity.

Innovation vs. Conformity

Metaphor gets to the root of this war between innovation and conformity. The habit of thinking in creative, new and imaginative ways is central to being inventive, resourceful and innovative.

Note that all of these words are synonyms of “productive” and ultimately of “progressive.” If we want progress, we must have innovation, and innovation requires imagination. Few things spark creativity, imagination or inspiration like metaphor.

If we want to see a significant increase in freedom in the long term, we’ll first need to witness a resurrection of metaphorical thinking. This is one reason the great classics are vital to the education of free people. The classics were mostly written by authors who read widely and thought deeply about many topics, and even more importantly most readers of classics study beyond narrow academic divisions of knowledge and apply ideas across the board.

In contrast, modern movie and television watchers, fantasy novel or technical manual readers, and internet surfers don’t tend to routinely correlate the messages of entertainment into their daily careers. There are certainly deep, profound, classic-worthy ideas in our contemporary movies, novels, and online. But only a few of the customers watch, read or surf in the classic way—consistently seeking lessons and wisdom to be applied to serious personal and world challenges.

Only a few moderns end each day’s activities with correspondence and debate about the movies, books and websites they’ve experienced with other deep-thinking readers who have “studied” the same sources. Facebook can be used in this way, but it seldom is.

Alvin Toffler called this the “Information Age” rather than the Wisdom Age for this reason—we have so much information at our fingertips, but too little wise discussion of applicable ideas. As Allan Bloom put it in The Closing of the American Mind, people don’t think together as much they used to. Even formal students in most classes engage less in open dialogue and debate than in passive note-taking and solitary memorizing.

Leadership Thinking

All of this is connected with the decline of metaphorical thinking. The point of education in the old Oxford model of learning (read great classics, discuss the great works with tutors who have read them many times and also with other students who are new to the books, show your proficiency in creative thinking in front of oral boards of questioners) was to teach deep, broad, effective metaphorical thinking.

All of this is connected with the decline of metaphorical thinking. The point of education in the old Oxford model of learning (read great classics, discuss the great works with tutors who have read them many times and also with other students who are new to the books, show your proficiency in creative thinking in front of oral boards of questioners) was to teach deep, broad, effective metaphorical thinking.

Such skills could accurately be called leadership thinking, and generations of Americans followed the same model (until the late 1930s) of reading and deeply discussing the greatest works of mankind in all fields of knowledge. Note that thinking in metaphor naturally includes literal thinking– but not vice versa.

This style of learning centered on the student’s ability to see through the literal and understand all the potential hidden, deeper, abstract, correlated and metaphorical meanings in things. Such education trained people to think through—and see through—the promises, policies and proposals of their elected officials, expert economists, and other specialists, and to make the final decisions as a wise electorate not prone to fads, media spin or partisan propaganda.

A New Monument

As a society understands metaphor, it understands politics. This is a truism worth chiseling into marble. When the upper class understands metaphor while the masses require literality, freedom declines.

The surest way to understand metaphor is to read literature and history and think about it deeply, especially about how it applies to modern realities (which is why classrooms were once dedicated to discussion about important books, as mentioned above).

This is why the university phrase “I majored in literature, science, or history” is a middle-class expression while the upper class prefers to say, “I read literature, science, or history at X University.”

The differences here are striking: the upper class never believes it has actually “majored” a topic, while the middle class can seldom claim to have seriously “read” all the great works in any important academic field.

This fundamental difference in education remains a cause of the widening gap between upper and middle class. Indeed, education is a major determining factor of the contemporary (and historical) class divide. It is the ability to think metaphorically (to in fact consider everything both literally and metaphorically) and to automatically seek out and consider the various potential meanings of all things, that most separates the culture of the “haves” from the global “have-nots.”

The Ideology Barrier

In politics, the far left and far right—including, most notably right now, the environmental movement and the tea parties—significantly limit their own growth by staying too literal.

This comes across to most Americans as ineffectively rigid, intolerant, naïve, and even ideological.

The fact that most environmentalists and tea partiers are genuinely passionate and sincere is not a plus in the eyes of many people as long as such activists are seen to be humorless and even angry.

Such activists may not in fact be humorless and angry, but when they seem to be these things, they diminish their ability to build rapport with anyone that does not already understand their point of view.

Feminism once carried these same negatives, but recently gained more mainstream understanding once feminist thinkers moved past literality and used art and entertainment to gain positive support. The gay-lesbian community made the same transition in the past two decades, and environmentalism is starting to make this shift as well (witness the recent hubbub over Cars III).

Whether you agree or disagree with these political movements is not the point; they gain mainstream support by portraying themselves as relaxed, happy, caring and likeable people, and by sharing their principles by telling a story.

False Starts, or, Failed Expectations

President Bush attempted to effect such a change in the Republican Party with his emphasis on Compassionate Conservatism, but this theme disappeared after 9/11.

President Obama exuded this relaxed optimism through the 2008 campaign and several months into his presidency, becoming a symbol of change and leadership to America’s youth (who hadn’t had a real political hero since Ronald Reagan). The president’s cult-hero status disappeared when the Obama Administration’s literality (not liberality) was eventually interpreted as robotic, smug and even defensive.

The White House’s big-spending agenda in 2009-2010, coming on the heels of over seven years of Republican-led overspending, sparked a tea party revolt. It also drove most independents to the right, not because they supported right-wing policies but rather because independents tend to understand metaphor: they saw that the Obama agenda was primarily about bigger government and only secondarily about real change.

To put this as literally as possible, President Obama desired lasting change in Washington, but he cared even more about certain policies which required massive government spending.

There are true supporters of real freedom on all sides of the political table: Democratic, Republican, independent, blue, red, green, tea party, etc. They would all do well to spread deep, quality, creative, artistic and metaphorical thinking in our society.

As Lord Brougham taught:

“Education makes a people easy to lead, but difficult to drive; easy to govern, but impossible to enslave.”

He was speaking not of modern specialized job training but of reading the greatest books of mankind. Leaders are readers, and so are free nations.

Symbolism, Nuance and the Deficits of Literalism

As long as metaphor is missing in our dialogue—not to mention much in our prevailing educational offerings—the people will be continually frustrated by their political leaders.

Campaigns succeed through symbolism, especially metaphor, while daily governance naturally requires a major dose of literalism. Sometimes a significant crisis swings the nation into a period of metaphor, but this mood seldom lasts much longer than the crisis itself.

The most effective leaders (e.g. Washington, Jackson, Lincoln, the Roosevelts and Reagan) are able to communicate a metaphor of American grand purpose even while they govern literally. For example, the Jeffersonian “era” lasted for decades beyond his term of office, building on the American mind captured by the metaphor of freedom; John Adams’ literalism hardly carried him through his one term.

While some of this is the responsibility of the leader, it is ultimately the duty of the people to think in metaphor and understand the big themes and hidden nuances behind government proposals and policies.

In this regard, groups such as environmentalists and tea parties seem to really understand the major trends and are courageously making their voice heard. Unfortunately for their goals, they have yet to effectively present their messages using metaphor. People tend to see them, as mentioned above, as humorless, angry and ideologically rigid.

The irony is rich, because most Americans actually support both a higher level of environmental consciousness and a major increase of government fiscal responsibility. In literal terms, many Americans agree with a large number of green and tea party proposals even as they say they dislike the “environmentalists” and the “tea parties.”

Again, the problem is that these groups tend to emphasize only the literal.

Such examples may be interesting, but the real problem for the future of American freedom is a populace that doesn’t naturally think through everything in a metaphorical way.

A free society only stays as free—and as prosperous—as its electorate allows.

When a nation has been educated to separate its thinking, it tends to be easily swayed by an upper class that understands and uses metaphor—in politics, economics, marketing, media, and numerous walks of life. It becomes subtly enslaved to experts, because, quite simply, it believes what the experts say.

Alternate Timeline of Literalism

If the American founding generation had so believed the experts, it would have stuck with Britain, would never have bothered reading the Federalist Papers, and would have left governance to the upper class.

The capitol would probably be New York City, and the middle class would have remained small. We would be a more aristocratic society, with an entirely different set of laws for the wealthy than the rest.

Such forays into theoretical history are hardly provable, but one thing is clear: American greatness is soundly based on a citizenry that thought independently, creatively, innovatively and metaphorically. The educational system encouraged such thinking, and adult discourse continued it throughout the citizen’s life.

Great education teaches one to listen to the experts, and to then take one’s own counsel on the important decisions.

Indeed, such education prepares the adult to weigh the words of experts and all other sources of knowledge and then to choose wisely.

Sit in chair; open book. Read.

Metaphor matters. Metaphorical thinking is vital to freedom. The classics are the richest vein of metaphorical and literal thinking.

Every nation that has maintained real freedom has been a nation of readers—readers of the great books. Freedom is in decline precisely because reading the great classics is in decline. Fortunately, every regular citizen can easily do something to fix this problem.

The books are on our shelves.

For more on this topic, listen to “The Freedom Crisis.”

Click here for details >>

***********************************

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

Oliver DeMille is a co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of Thomas Jefferson Education.

He is the co-author of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestseller LeaderShift, and author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, and The Coming Aristocracy: Education & the Future of Freedom.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah.

Category : Aristocracy &Arts &Blog &Culture &Current Events &Education &Featured &Generations &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Politics