Don’t Miss This Book!

April 15th, 2019 // 9:44 am @ Oliver DeMille

A Note from Oliver DeMille…

Summer – 1985 or 1986: I couldn’t believe it. I found myself holding my breath. Hanging on every word, page after page, waiting to see if freedom would be lost forever… Could they fix it? Or was it too far gone? And how could they get back their freedoms if they waited any longer?

I was a teenager at the time, and I had no idea that I would eventually dedicate much of my adult life to studying and promoting freedom, and the great principles upon which freedom is based.

But I don’t think I would have become a serious student or promoter of freedom without reading two books – both of which made me fall head-over-heels in love with freedom, and inserted deeply into my heart and mind why it matters.

The two books were The Alliance by Gerald Lund and The Making of America by [the man who later became my personal mentor] Cleon Skousen, and they changed my life. I truly came to love freedom as I read them during one hot summer in the family home where I grew up.

The Battle for our Youth

Today I look around at the rising generation – over 50% of whom (in the United States) say they like socialism. I look at the lack of interest in freedom among so many young people, and I worry about the future. After all the blood and tears that the Founders, pioneers and so many soldiers paid for our freedoms, why can’t everyone see how important this is? We can’t remain free if the youth don’t care about it, or if they think socialism is a better path. But just caring about freedom isn’t enough. We need the younger generation to truly fall in love with freedom.

Nothing else will prepare them to be the kind of people who stand up for freedom and right and make sure it isn’t lost.

I’m writing today to highly recommend a new book that I believe will have the same kind of impact on those who read it – inspiring them to fall deeply in love with freedom. Or, if they already care about freedom, as many do, to love and cherish it even more.

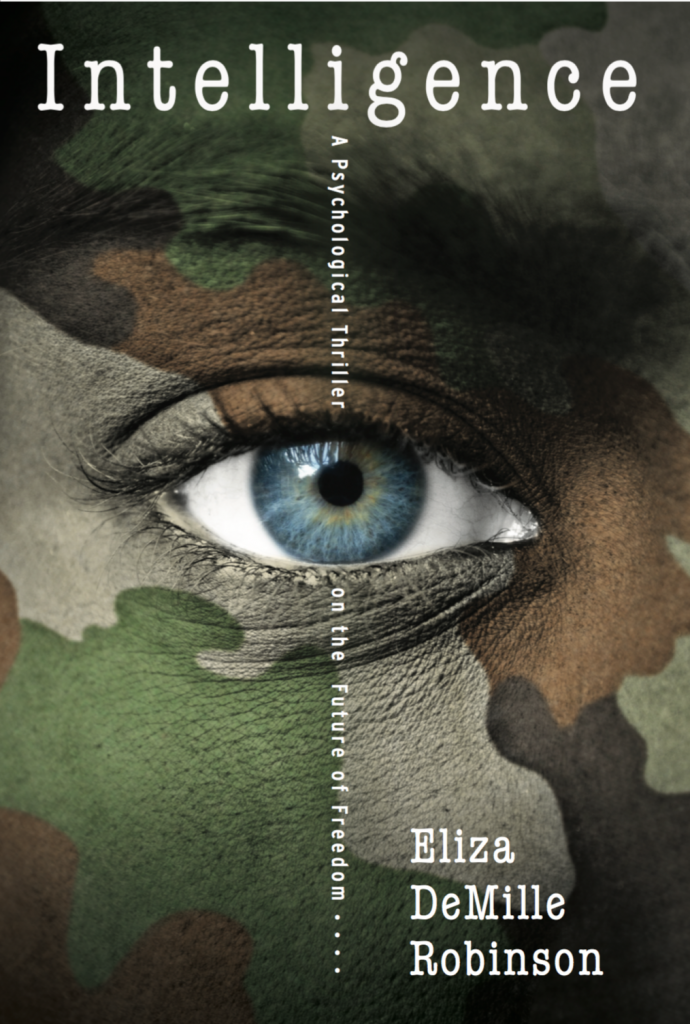

The book is Intelligence, written by Eliza DeMille Robinson, my daughter and mentee during over 20 years of personalized homeschool mentoring.

This is a dystopian novel, with real answers for the real world – plus a bit of an epic on the future of freedom, and a truly excellent read. I smile as I review it, seeing the years of study in history, leadership, freedom, government, literature, classics, science and other books with discussions!

I see all that she discovered – we discovered together – now poured into the plot and characters. The book depicts a near-future world torn apart by the battle between freedom and socialism, and paints a realistic and challenging picture of where we may be heading in our modern society if the conveyor-belt system of education keeps expanding at its current pace!

It speaks directly to people today, both those in the rising generations and their parents. It is a powerful message for this time, our specific time, in history.

TJEd is proud to promote this important new book, because we consider Intelligence a must-read for anyone who loves freedom, great education, and sees the increase in value and need for Leadership Education in our world today.

Eliza has been writing and rewriting this book for five years, and I have watched it develop from a good idea into a solid story by a student, then into an excellent book in its own right–and, during the last year, into a truly great book with an important message for everyone in our current generation.

It’s exciting to now see it published. I think this book is especially powerful for today’s youth, to help them value freedom, love learning at an even deeper level, and actually fall in love with freedom–something that is increasingly and tragically rare in the rising generation.

This is a great book, a life-changing book! We are proud to promote it to everyone who cares about the direction modern education is too often taking many families and our world, and all who care about the freedoms that are being lost almost daily.

Don’t miss this great book – for youth, for parents, and the whole family. The time for such a story is now, while we can still make a difference for freedom.

Prepare to be inspired…

January 2019: I realize that once again I’m holding my breath, caught up in the intensity of the story. This feels just like it did back then. I inhale deeply as I turn the page; then as I read about dear Brianna’s decision, the tears come. Then the sobs; my mind is reeling. I keep thinking: freedom is worth it. So worth it. I wipe away the tears and keep reading…

What are readers saying?

“A dystopian novel worthy of sitting beside titles like The Hunger Games and The Giver, Intelligence tells a story that is crucial to our rising generation. Excellent for teens and adults, its deep and plentiful messages remind readers about the impact of our current decisions on our future, providing hours of discussion time after just a single chapter!”

~Jonathan D. Martin, 14yo TJEd High student

“I’m a huge fan of dystopian fiction. Intelligence goes even a step above and beyond what we have read in current fiction. It not only has an original and intriguing plot, but it illustrates true principles to keep our country free. This is must read for my teens! Robinson is a captivating author. I look forward to reading much more of her work!”

~Toni Nelson

“Deeply thought provoking, couldn’t put it down, then couldn’t wait to discuss it with friends and family! So much here: what a personal life mission looks like, how it is discovered; the basic premise of freedom on all levels from national/governmental to individual/personal; sacrifice and what is worth the sacrifice; what is good, what is evil and what determines that all wrapped up in a captivating, moving storyline. ”

~Sarah Teichert

“More than anything, Intelligence, By Eliza DeMille Robinson, whet my palate for more! In this first book, you get a thrilling journey through the souls of unique and interesting individuals as they discover what is worth fighting and sacrificing for. The individual, the collective, the very state of the world hangs in the balance as the dedicated few battle for freedom, truth, and all that is right and worthy in the world. It’s a bit dystopian, a bit sci-fi, a bit coming of age, a bit a hero’s tale, a bit treatise on the future of the human race! The world Eliza builds will all ring a bit disturbingly true and you’ll come to take a moment to search your soul as the characters search theirs and find their true calling and power as individuals.”

~Lisa Paul

Excellent for gifting, book clubs, and family discussion! Purchase your copies today!

Category : Blog &Book Reviews &Culture &Education &Featured &Government &History &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Politics &Statesmanship

Jefferson-Madison Debates: A Week of Socialism

August 21st, 2018 // 2:21 pm @ Oliver DeMille

The Media of Our Time

This week I read five books, and one of them was an easy, enjoyable novel—a western entitled Flint that I’ve read and reread several times. Surprisingly, it was the western that first got me thinking about socialism. It contains a classic East Coast vs. Wild West milieu, where the main character experiences and ultimately chooses the fiercely independent lifestyle of the West over the more “socialized” culture of New York and New England. When I read the other four books they kept challenging my mind with similar themes—the kind that woke me up in the night numerous times with “new” thoughts that somehow refused to wait for morning. Fortunately, I keep a notebook on the nightstand for just such events.

This week I read five books, and one of them was an easy, enjoyable novel—a western entitled Flint that I’ve read and reread several times. Surprisingly, it was the western that first got me thinking about socialism. It contains a classic East Coast vs. Wild West milieu, where the main character experiences and ultimately chooses the fiercely independent lifestyle of the West over the more “socialized” culture of New York and New England. When I read the other four books they kept challenging my mind with similar themes—the kind that woke me up in the night numerous times with “new” thoughts that somehow refused to wait for morning. Fortunately, I keep a notebook on the nightstand for just such events.

Watching and reading the news added to this mental battle, since socialism is making a serious comeback right now in some corners of American politics. But mostly my thoughts centered on the books themselves. The first one after the western got the ball rolling because it openly promotes socialism, the cooperative type that focuses more on economics and culture than politics. It really made me think, because it skipped theory and emphasized current actions. Sobering.

Then I kept reading, and all the books were deep—nothing to skim. Every word was important; every sentence and paragraph deserved consideration.

By the time I finished the last book, I had a lot of ideas bouncing around in my head. As mentioned, the first book was about cooperatives as a replacement for corporate greed—putting “democracy” back in the business world, as the author put it, and a second offered a detailed history of the Supreme Court’s impact on American public education (and its governmental/legal influence on non-public education as well). There are a lot of socialist ties in education, sadly.

The third book amounted to a warning. China is growing—in power, wealth, and global ambition. We seldom hear much in the media about the major China threat, even though it is increasing at a staggering pace. Xi Jinping has centralized power within the People’s Republic of China to a level unprecedented since Mao (some would say with more power than Mao, given China’s huge economy and global reach). China’s plans for the decade ahead are remaking the globe. Yet, again, this is a topic hardly discussed in current America. Both communism and socialism refuse to die or go away; in some ways they are powerfully ascendant right now.

Finally, the last book, really just excerpts from a book that hasn’t yet been fully released, shares Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s thoughts about his famous 1978 speech at Harvard. If you’ve ever read A World Split Apart (the Harvard speech), you know it is important, and incredibly powerful. Every idea is profound, and unexpected. The excerpts from his new collection, to be published in late 2018, are equally compelling. In 1978 his words seemed a lot more anti-capitalist than anti-communist or even anti-socialist, but today I kept noticing the way his commentaries on America’s mainstream media crisply poke holes in an industry that has arguably become the world’s leading apologist for socialism. Deep. And this historical trend from 1978 has now become a tidal wave.

Following are my notes and main conclusions on these four books. I think they’re worth considering. There is a lot of important information packed into this article. If you give these ideas a chance, I think they’ll help you think even more deeply—and I hope more wisely as well—about our current events and challenges. It seems increasingly true that in our age of rampantly-partisan media, books frequently tell us more about events than the nightly news. It may be that a return to books (even more than the growth of the Internet) is the actual “new media” of our time. So much of what calls itself media today isn’t journalism at all, but just entertainment for the two major political parties, or worse, strident muckraking. Here goes…

Book One

Everything for Everyone (by Nathan Schneider)

Everything for Everyone (by Nathan Schneider)

-

5 Stars for Importance

-

2 Stars for Promoting Freedom

-

4 Stars for Fun

Theme: Like it or Not, Socialism by Any Other Name is Still Socialism (But Capitalism is Either Really Bad or Really Good, Depending…)

The Problem, as described in Everything for Everyone, is that modern capitalism has become an enemy to democracy and culture. The book refers to the American economy as “A new feudalism on the rise” where “monopolistic corporations feed their spoils to the rich [while] more and more of us are expected to live gig to gig.” It traces the history of the idea that the best societies exist where the people share “all things in common”, from medieval monasteries and guilds to modern urban taxi cooperatives taking on Uber, from “freespace” supporters in San Francisco to online platforms, and numerous other examples.

The Solution, according to this book, is the spread cooperatives, groups democratically run by cooperating people—not dominating corporations controlled by a hierarchy of the elite few. Based on the marketing copy, the book appeared to promote an extremist utopia for utopians, which coincides nicely with the increasing popularity of socialism in the Democratic Party. The subtitle (“The Radical Tradition that Is Shaping the Next Economy”) predicts that this Solution is the clear way forward, our best path to a better future. And the author’s most recent book before this one, entitled Thank You, Anarchy: Notes from the Occupy Apocalypse, seems to reinforce this impression. But Everything for Everyone is a lot deeper than it seemed to me at first glance.

Indeed, as I read, I found myself marking numerous sentences, paragraphs, and quotes for future reference. The book is a treasure-trove of thinking on modern problems—clearly coming from a place Left of Center, but not patently anti-capitalist. Again, given the marketing copy, this surprised me. For example, while promoting the virtues of cooperation in very progressive-sounding language, the author also wrote: “Does cooperation count as capitalism, or something else?… If capitalism means freely associating in the economy, or ingenuity and innovation, or the rough-and-tumble of setting up a business, or price-based reasoning—then yes, cooperation overlaps with it. But if capitalism means a system in which the pursuit of profit for investors is the overriding concern, cooperation is an intrusion.”

To be clear, the term “capitalism” is often used in different ways by different people, and has evolved over time. Free Enterprise Capitalism (which promotes “freely associating in the economy… ingenuity and innovation… the rough-and-tumble of setting up a business…”) is not the same thing as Crony Capitalism or what is sometimes termed “Corporate Capitalism”—where institutions with capital are treated differently by government, law, and the commercial code. In Free Enterprise Capitalism, all people and institutions are treated equally by the law; in Corporate/Crony Capitalism the rich are given special legal and financial benefits. In my view, the real negative isn’t what Schneider calls “the pursuit of profit as the overriding concern”, but rather these special legal benefits that are both undemocratic and elitist, and also undermine Free Enterprise.

Overall, I consider this book a great read about our modern world. On the one hand, I heartily agree with its warning against the increasing dangers of government-by-corporate-powers, the Military-Industrial-Complex in its newest form, sometimes called The Black Box Society (another excellent book) or Government by Corporate Algorithm, Crony/Corporate Capitalism, or simply Elitism. The idea that economic progress must be a top-down process controlled by elites—while most people struggle paycheck to paycheck—is the source of many of our modern problems. More people on the Right need to understand and accept this challenge, because it’s real.

At the same time, I have mixed feelings about many of the proposed solutions in Everything for Everyone. Just like capitalism can adopt the empowering Free Enterprise approach or succumb to the controlling Crony/Corporate/Elitist model of capitalism, cooperative organizations and co-ops can be either freedom-supporting grassroots enterprises (which require a free economy if they want to flourish) or force-based. Where the author encourages the first, I like it. When the book promotes the second, not so much.

From the book: “What would it take so that a can-do group of pioneers—people with a need to meet or an idea to share with the world—might conclude that the best, easiest way to build their business is by practicing democracy?” Again, these words seem to lean toward freedom, and certainly the idea of more entrepreneurs and owners in our business structures is appealing. Even necessary, I think. But how easily does this approach turn into force-based controls? Is this joint-ownership system built on contract and market forces, or does it depend upon or even promote government forced “cooperation”? Both iterations will likely be applied.

The reality is that democracy is hard. The reason we use it in government is that government itself is force, and without a healthy dose of official voting power vested in the regular citizens, government will always be dominated by some group of elites—who seldom give the people any real equality (despite promises) or treat the people with respect, or allow any true freedom. And, secondly, the best governments, the free ones, check and balance democratic parts of government with branches that are aristocratic (e.g. Senate), appointed (e.g. Executive), and even appointed by the appointers (e.g. Judiciary).

This has been a long-established reality, even before Aristotle openly pointed it out. In the American arrangement of this model, the Framers made sure democracy had the final say (mostly through the power of the purse held by the democratically-elected House of Representatives), but not the entire say. Such a democratic republic is democratic, yes, but it’s not a pure democracy.

Thus, if most good democratic republics, where democracy has the final say through the purse strings, end up losing their freedoms to aristos and elites (and they do, as Madison pointed out in The Federalist), how much more quickly will this decline occur in democratic cooperatives? On a side note, as I read Everything for Everyone, I kept thinking of another book, similar in some very important ways, entitled Beyond Capitalism and Socialism, edited by Tobias J. Lanz. These two books are worth reading together, comparing and contrasting. Also throw into this conversation the book Give People Money, by Annie Lowry, which I reviewed earlier this year.

Finally, in addition to the important ways Everything for Everyone contributes to the discussion of where we want our economy to go, it is also a valuable book on current politics. For those on the Left, it shares a number of ways people are trying to seek a better economic model for the future—real people, doing real projects. Not just theory, which is often the Achilles heel of proposals from the Left. This provides the most value in the book, in my opinion. For those on the Right, this book strips away many of the stereotypes and misconceptions about the modern Left (the mainstream media version), and will help conservatives and independents understand more deeply what many on the Left are really about. Understanding this is important for everyone.

Book Two

The Schoolhouse Gate (by Justin Driver)

The Schoolhouse Gate (by Justin Driver)

-

5 Stars for Importance

-

3 Stars for Freedom

-

3 Stars for Fun

Theme #1: The Court Gets a Lot of Things Wrong (And It’s Okay to Say So Out Loud…)

Theme #2: The Court is Far Too Involved in Education (The Constitution Mostly Left this to the States, But Try Telling That to the Court…Or Congress, the White House, or Anyone Else in Washington)

First of all, I like that this book seems to take a 3-branch view of the Constitution (that the Supreme Court can be wrong, and often is, and that the Legislative and Executive branches are co-equal with the Judiciary) rather than the erroneous 1-branch view that the Court is the final and highest power in the nation. The 1-branch view is much more common in today’s world, especially in the mainstream media. Putting the topic of education aside for a moment, the 3-branch approach makes this book a rarity, one that is a must-read work for anyone interested in the modern Court. (Another book that effectively speaks from the 3-branch approach, with more specifics, is Constitutional Law by Nowak and Rotunda, Seventh Edition.)

As mentioned, The Schoolhouse Gate is laced with the idea that the Court is sometimes wrong. For example, the author says: “The Supreme Court has also stumbled…” and calls one landmark case “a Constitutionally questionable decision…” The federal Courts in general are said to make “many wrongheaded decisions…” The book is filled with such language, a refreshing approach in our time. Also, one of the best things about this book is that is written for the regular reader, not limited to a few legal scholars.

The focus of The Schoolhouse Gate—Court decisions and trends dealing with American education over time, including recent cases—is must-know information for all informed Americans. In historical scope, it reminds me of Constitutional histories by Forrest McDonald, but with more detail. Most people today don’t know the information outlined in The Schoolhouse Gate; making Driver’s book all the more important. I didn’t agree with all the book’s conclusions, but I did agree with many—and either way the book consistently caused me to think about things I had never really considered.

In my view, the Court has made a few very important decisions about education that are really good for our nation, and a number of bad decisions that aren’t. In most cases, it would be better to leave educational decisions to the states, as per the Constitution. A question that kept recurring in my mind as I read: “Is the Court approach to education rooted more in individual liberty or collectivist socialism?” The answer is far too often, though not always, the latter.

Largely as a result of this, today’s modern schools are in many cases de facto incubators of socialism—from mild to more extreme. This applies not only to elementary and high schools, but to most of higher education as well. The drive is to make schools as similar as possible, often under the guise of “equality” and a professorate made up not just largely, but almost entirely of progressives. Conservatives are a rarity in nearly all the top American institutions of higher learning. In far too many cases, conservative students are penalized for their political views—and a lot of them hide or even change their politics during their time on campus.

What happens to a society where many of the children are raised in conservative or conservative-leaning homes, educated in elementary/secondary schools that lean strongly Left, and then trained in “higher” institutions with a fundamental and passionate allegiance to the Left? In many cases the conservatism of parents and grandparents is mocked as childish, and Leftism is ultimately considered truly “higher” (meaning “better, more advanced, more correct”) learning. The “adults” and “grown ups” in such a model must, by definition, come from the Left (or, if Republican, of the progressive type). This is the fruit of thirty years of infiltration in lower schools and on campus, frequently supported and even encouraged by Court decisions.

Book Three

The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State

The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State

(by Elizabeth C. Economy)

- 5 Stars for Importance

- 4 Stars for Freedom

- 3 Stars for Fun

Theme: While the Media is Overwhelmingly Obsessed with Russia, the Threat from China is Growing at an Alarming Rate

The next ten decades belong to China, if ownership and contractual access to the world’s natural resources are any indication. Historically, these are always the best indication of what’s ahead. Yet, astoundingly, few in current America are giving this the attention it demands. The United States literally may face an existential threat from China in the decades ahead.

Elizabeth C. Economy’s book The Third Revolution makes the case that there have been three great eras in modern China: (1) the Maoist Revolution that brought communism to China, (2) the “Second Revolution” led by Deng and those who came after him, which emphasized more openness—both in China’s domestic economy and in relations with the outside world, and (3) the current “Third Revolution” which focuses on increasing the power of one leader within the nation, Xi Jinping, and boosting China to the pinnacle of power and leadership on the global stage.

Consider the following quotes from Economy’s book:

“The ultimate objective of Xi’s revolution is his Chinese Dream—the rejuvenation of the great Chinese nation…. Xi’s predecessors shared this goal as well. What makes Xi’s revolution distinctive is the strategy he has pursued: [1] the dramatic centralization of authority under his personal leadership; [2] the intensified penetration of society by the state; [3] the creation of a virtual wall of regulations and restrictions that more tightly controls the flow of ideas, culture, and capital into and out of the country; and [4] the significant projection of Chinese power.”

“It represents a reassertion of the state in Chinese political and economic life at home, and a more ambitious and expansive role for China abroad.”

“Unlike his immediate predecessors, he has assumed control of all the most important leading committees and commissions that oversee government policy; demanded pledges of personal loyalty from military and party leaders; eliminated political rivals through a sweeping anticorruption campaign…. [A]dvocates for change or those who seek a greater voice in political life, such as women, labor, or legal rights activists, increasingly risk detention or prison.”

This new approach goes well beyond international economic expansion. For example, as Economy shows, since 2014 Xi’s government has driven “massive land reclamation and militarization of the islands in the South China Sea…. He has established China’s first overseas military logistics base; taken significant [steps to increase]…strategic ports in Europe and Asia; championed China as a leader in addressing global challenges, such as climate change [with China’s largest competitor, the United States, largely footing the bill]; and proposed a number of new trade and security institutions [and a PRC-dominated world reserve currency to replace the U.S. dollar]. Xi seeks to project power in dramatic new ways and reassert the centrality of China on the global stage.”

Note that all of these initiatives and changes began during the Obama era, while the United States struggled in the aftermath of the Great Recession. The economic rebound of the United States, beginning in 2017 and corresponding with a more aggressive foreign policy under the Trump Administration, has changed the dynamic of Chinese-American relations, but China hasn’t changed its trajectory.

Economy points out the drastic significance of the situation:

- “[A]ll the major economies of the world, save China, are democracies.”

- “China is an illiberal state seeking leadership in a liberal world order.”

I consider this one of the most important books of our time. As I’ve said about the other books reviewed here, it is a must-read for anyone who cares about America. And the future of the world, for that matter. It’s that significant.

Economy’s proposed policies and solutions are particularly interesting. Whether you agree with them, or part of them, or disagree, they bring up topics that demand a lot more consideration and discussion by regular Americans. If we don’t engage such conversations, we leave public policy and national direction to a few experts in academia, think tanks, media, and government. This is hardly the American way, though it has dangerously become the norm in many policy debates during recent decades.

An example of Economy’s suggestions is the need to recognize the influence that China now has on American campuses, and how important it is for Americans to learn what is occurring. She wrote: “China under Xi Jinping also seeks to influence the domestic politics of other countries as those politics relate to China. The Chinese government mobilizes students and other citizens living abroad to represent the interests of the Chinese government by, for example, spying on other Chinese students, denouncing professors who offer contrarian opinions [isn’t the purpose of universities in a free society to allow open discussion of differing ideas?], and protesting against invited speakers who criticize China.”

In reality, the media obsession with Russian influence on American elections is ironic given the sheer scope and scale of China’s much bigger presence and influence—not just in the U.S. but also in Europe and around the world. This mirrors the general silence about China (again: the world’s second largest economy, which now rivals the U.S. economy) and daily onslaught of commentary on Russia meddling (the same Russia whose economy is only about half the size of the economy of California). American citizens need more perspective on what’s really happening.

As Economy recommends to the Trump Administration: “… the United States can gain leverage in negotiations with China by understanding domestic dynamics within the country around particular issues.” The interest of Chinese citizens in the English language and American culture, politics, business and society dwarfs the level of American interest or focus on anything Chinese. Our lack of seriousness in this respect is dangerous.

Whether the future will actually be dominated by China remains to be seen. But it is certainly a real possibility, and we are right now on track to see this outcome. If it occurs, it could very well spell disaster for freedom.

Book Four

Between Two Millstones, Book I (by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Peter Constantine)

Between Two Millstones, Book I (by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Peter Constantine)

-

5 Stars for Importance

-

5 Stars for Promoting Freedom

-

5 Stars for Fun

Theme: Just Read It—It’s Awesome

When Solzhenitsyn spoke at Harvard in 1978, he caused a firestorm of media criticism. Many expected him to describe the weaknesses and evils of communism, and show the many ways America and the West are better—as he had done in earlier speeches. But at Harvard he targeted a different problem: the systemic flaws and mistakes of Western Civilization, especially in the United States. He attacked the way we do business, our legal system, our colleges and universities, our culture (or more accurately, the ways we lack culture), and above all our modern media.

Decades later, in Between Two Millstones, we get to read and think about his critique of how his speech was received, and why it matters. This provides one of the most poignant descriptions of modern media available. If you haven’t read his speech, published as A World Split Apart, it’s worth studying before you read Two Millstones. Together they provide a powerful commentary, one we should all engage and consider.

Specifically, concerning what we today call the mainstream media, Solzhenitsyn points out that our roots are muddled: “Western society is based on a legal level that is far lower than the true moral yardstick…” Because of this, he argues, we tend to consider something good as long as it is legal, and we usually apply this to all parts of society, including business, family, education, media, etc. Thus media can say whatever it wants, as long as it is legal. Indeed, media doesn’t have to stand for truth, or accuracy, as long as what it says is legal by the letter of the law.

The result is a major power grab, albeit a somewhat subtle one. Solzhenitsyn wrote: “And above all, the press, not elected by anyone, acts high-mindedly and has amassed more power than the legislative, executive, or judicial power.”

This should make every American stop and think deeply. It didn’t quite reach everyone in 1978, but it is still relevant.

He continued: “And in this free press itself, it is not true freedom of opinion that dominates, but the dictates of the political fashion of the moment, which leads to a surprising uniformity of opinion.” He points out that this is the thing that “irritated” the mainstream media the most about his speech. Claiming to be champions of diversity and open thinking, the media is often the enemy of both.

Here are some of the bad habits and underhanded tactics of the mainstream media, as suggested by Solzhenitsyn:

- They “completely” missed the things Solzhenitsyn thought were important about the speech, the very things the speech was actually about, and focused on their own agenda—misrepresenting and tangentially citing his message in order to make it fit their narrative so they could attack it. He called this “a remarkable skill of the media”.

- “They…invented things that simply did not exist in my speech”.

- They “prepared their responses in advance”, and focused their commentary not on what he actually said but on their plans to discount what they anticipated he would say—ready to pounce and then twisting phrases and words to make connections with their pre-designed rebuttals.

- They didn’t just misreport the facts, but in addition “the press spouted scalding invective…” They did this without telling the populace that these were just the opinions of the reporters; instead they acted as if their “invective” and anger were objective and wise. Even true. In reality it was only their opinion, and frequently differed from the facts and what he actually said in the speech.

- Overall the media tends to reject and attack those who criticize them, and reward only those who “flatter” them.

Of course, he expected the mainstream media to disagree with him. After all, he frequently and openly accused the media of many mistakes, including “stuffing” the people’s “souls…with gossip, nonsense, vain talk.” They naturally pushed back.

What did surprise him is what happened in another part of America, away from the centers of power. Solzhenitsyn wrote:

“…one could also begin to read many responses that were markedly distinguished from the arrogant stance of the America of New York and Washington… Gradually another America began unfolding before my eyes, one that was small-town and robust, the heartland, the America I had envisioned…. I now felt a glimmer of hope…”

From the local and non-mainstream media he heard such responses as:

- “We know in our hearts he is right…”

- “His speech ought to be burned into America’s heart. But instead of being read, it was killed” by the mainstream media.

- “Can the press maintain diversity when ultimate control [of the media] rests in the hands of a small group of corporate executives?”

The two Americas were already a reality in 1978. But, like always, the mainstream media paid little heed to the media of “the heartland” or the views of non-elite Americans. To get the real story on things, people will apparently have to see past the mainstream media and find more truthful and more, well… journalistic… sources—and concerning his speeches and books, nothing is better than the original words of Solzhenitsyn himself.

From what I can tell from the early excerpts that are available to read, Between Two Millstones will be a great book, an important read, and one that will make every reader think and rethink. To be published in late 2018, forty years after the Harvard speech, it should be read by everyone who cares about our society and its future.

Conclusion

My stroll through these four books this week (five, if you count the western), with their recurring theme of socialism, from various angles, has prompted me to move even further past the old view that liberalism and conservatism are the dominant political forces of our time. I am increasingly convinced that socialism is powerfully on the rise right now (both in the U.S. and around the world), and that it presents a clear and present danger to freedom.

Above all, I am more convinced than ever of just how important it is for those who care about freedom to read more and raise the awareness of what is at stake in the months and years just ahead. I think books are the true “new media”, while most mainstream news outlets and platforms are mired in non-journalistic battles to promote false narratives. This demands that we, the regular people, take action to dig a lot deeper in our own study of what’s really happening.

A few final questions:

-

What important things are you reading this week and month?

-

What are the “theme units” you’re finding in what you read?

-

Are you writing down your thoughts?

-

With whom are you sharing what you are learning?

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Book Reviews &Business &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Education &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Politics

The Jefferson-Madison Debates: To Pay, or Not to Pay…

June 12th, 2018 // 10:12 am @ Oliver DeMille

Tackling a Universal Basic Income

(Book Reviews: Annie Lowrey, 2018, Give People Money;

Richard Weaver, 1948, Ideas Have Consequences [2013 reprint])

“Neither parents nor children have any other prospects than what are founded upon industry, economy, and virtue…. Hence arises a spirit of universal activity, and enterprise in business…. No difficulty or hardship seems to discourage them.”

—Samuel Williams, History of Vermont, 1794

“Buy that latte and a child dies.”

—Esquire, The Money Issue, April 2016

Up or Down

I recently saw a cartoon that made me smile. If I remember correctly, it portrayed a Raptor on the left, an ostrich-like creature in the middle, and a chicken [Editor: Kiwi, actually?] on the right. The caption read:

EVOLUTION

MISTAKES WERE MADE

I laughed pretty hard. If evolution really did go from raptors to chickens, Darwin’s survival of the fittest and natural selection leave a lot of questions. Funny.

I laughed pretty hard. If evolution really did go from raptors to chickens, Darwin’s survival of the fittest and natural selection leave a lot of questions. Funny.

A similar energy frequently invades modern public policy. Far too many government programs seem to accept that if we have the right goals in mind, if our heart is in the right place and we’re really trying to fix things, it doesn’t matter much if we legislate in a way that will actually solve the problems. Just trying is, apparently, enough.

For example, we want better education for our youth, but if throwing more money at public schools would really fix the problem, we’d be ahead of Japan, the United Kingdom and Switzerland in language, math, and science. In fact, the U.S. ranks 17th overall among industrialized nations (Source: Ranking America), and while we rank first in expenditures per student (over $12,000 per year for each high school student), American 15-year-olds score 31st in math literacy and 23rd in science (Source: CBSnews.com). Clearly something more than additional funding is needed—like a re-emphasis on real teaching, which means mentored personalization for each student. Instead, government programs keep throwing more money at schools in ways that don’t help, as if trying harder is somehow good policy.

Likewise, if passing tougher gun laws would seriously solve or even significantly reduce violent crime, they might make sense. But since the statistics clearly show that such laws don’t fix the problem (criminals don’t really follow them, after all), why are we still even debating the topic? Why is it a good idea to have the law-abiding citizens unarmed and the criminals armed to the teeth—as a direct result of government policy—is pretty much mindboggling. But at least somebody is trying, right?

Better than Bad

One more example: if we really could significantly reduce the cost of health care for everyone, and at the same time insure everyone, keep the same doctor, and keep the same healthcare provider, who wouldn’t want that? But Obamacare was promoted and passed even though many of the experts warned of exactly what happened—premiums skyrocketed, many people had to change their healthcare providers, a lot of companies and states pulled out, and a lot of people couldn’t keep their doctor. “We had to try, though, didn’t we?” Some Americans apparently still think this is a sound basis for government policy. We subscribe to the kindergarten mentality of “‘A’ for effort,” or “‘A’ for intention” –regardless of principles or outcomes.

One more example: if we really could significantly reduce the cost of health care for everyone, and at the same time insure everyone, keep the same doctor, and keep the same healthcare provider, who wouldn’t want that? But Obamacare was promoted and passed even though many of the experts warned of exactly what happened—premiums skyrocketed, many people had to change their healthcare providers, a lot of companies and states pulled out, and a lot of people couldn’t keep their doctor. “We had to try, though, didn’t we?” Some Americans apparently still think this is a sound basis for government policy. We subscribe to the kindergarten mentality of “‘A’ for effort,” or “‘A’ for intention” –regardless of principles or outcomes.

In short, when we don’t understand human nature, we make mistakes. Numerous governmental attempts to solve our problems could be labeled:

GOVERNMENT PROGRAM

MISTAKES WERE MADE

This time nobody’s laughing though, maybe because we realize that we are the chickens in the cartoon. And if you’ll forgive a mixed metaphor, now: Not a lot of people like being guinea pigs. We need a better standard for government policy than “But we have to try! It’s such a big problem, so even bad policy is better than no policy.”

And yet: Not so. Government policies sometimes make things worse, not better.

Part II

“Do you see the necessity of accepting duties

before you begin to talk of freedoms?

These things will be very hard,

they will call for deep reformation.”

—Richard Weaver, Ideas Have Consequences, 1948

“You need $1,000 today. How to get it.”

—Headline in Esquire, The Money Issue, April 2016

Open Account, Open Mind

Which brings us to a very important topic: A Universal Basic Income (UBI). The UBI has been recommended in one form or another by Mark Zuckerberg, Richard Branson, Ray Kurzweil, Bernie Sanders and others, and now Annie Lowrey’s new book Give People Money makes an energetic case for it. Lowrey’s subtitle outlines the major perceived benefits of the program: “How a Universal Basic Income Would End Poverty, Revolutionize Work, and Remake the World”.

Which brings us to a very important topic: A Universal Basic Income (UBI). The UBI has been recommended in one form or another by Mark Zuckerberg, Richard Branson, Ray Kurzweil, Bernie Sanders and others, and now Annie Lowrey’s new book Give People Money makes an energetic case for it. Lowrey’s subtitle outlines the major perceived benefits of the program: “How a Universal Basic Income Would End Poverty, Revolutionize Work, and Remake the World”.

“Imagine if every month the government deposited $1,000 into your checking account,” suggests the ad copy for Give People Money, “with nothing expected in return.” Interesting. Nothing expected in return? What about the taxes needed to fund the $1K per person across the nation, or the globe? That’s actually quite a significant expectation.

But I digress. Let’s keep an open mind and listen to Lowrey’s proposal. After all, even arch-conservative/libertarian thinkers Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek made a case for a Universal Basic Income, or something like it.

Hayek said:

“The assurance of a certain minimum income for everyone, or a sort of floor below which nobody need fall even when he is unable to provide for himself, appears not only to be a wholly legitimate protection against a risk common to all, but a necessary part of the great society in which the individual no longer has specific claims on the members of the particular small group into which he was born.”

Friedman suggested that in times of economic stagnancy, when consumers aren’t spending and producers aren’t creating, it might be prudent to jumpstart the economy by “helicoptering.” This consists of dumping large amounts of cash from helicopters, allowing people to pick up the money and spend it—thus rebooting business. Of course, the actual idea behind “helicoptering” was to deposit a predetermined amount of money into the bank accounts of large numbers of people, those making less than a certain amount of money, not actually throwing cash from helicopters. While this plan focused on a one-time event, not a monthly deposit like most Universal Basic Income proposals, the principles are reminiscent.

Ends and Beginnings

To many conservatives, it makes sense that liberals, progressives, and socialists would endorse the idea of a Universal Income. But the same basic support from both Hayek and Milton Friedman is a head-scratcher.

To many conservatives, it makes sense that liberals, progressives, and socialists would endorse the idea of a Universal Income. But the same basic support from both Hayek and Milton Friedman is a head-scratcher.

In context, Hayek seems to have made this proposal as an alternative to entrenched socialism: a system where most or all of the jobs are controlled and distributed by government. In such an environment, a Universal Income would actually provide the opportunity for a budding free market, a chance for entrepreneurship, or “to relocate” to another nation with more freedom. (See Matt Zwolinski, “Why Did Hayek Support a Basic Income?” Libertariansim.org).

Lowrey’s proposal, in contrast to Hayek, is set in our current world. Or, more precisely, in a better world built on this one. The benefits of the program would be, mainly:

*End systemic poverty. By “hacking poverty”, we could eliminate much of the suffering and dead-end misery in the world (or nation). (Give People Money) Those who want more than the $1,000 per month, or whatever the UBI is, could work more or build a business, etc.—just like many people do now. But those who choose otherwise would at least have a basic living.

*Emphasize individual purpose. People could focus on doing work they love, rather than being tossed about by the cold demands of market forces. Individuals could emphasize their life purpose, and spend their days doing things they really care about. No more “crummy jobs.” (Ibid.) This might even help create a “groovy, Trekkie post-capitalist world without work”. (Ibid.)

*Improve social justice. It might even help nudge the world towards truly solving the problems of social injustice. “A UBI” Lowrey says, “would undercut the basis of such judgments [including racial, class, and gender discriminations] and be a powerful force for human dignity.” (Ibid.) It would also acknowledge “that our market economy leaves people out and behind, creating poverty and punishing individuals who cannot or are not working for an employer…. It would acknowledge our interdependence as well as our independence.” (Ibid.)

*Increase and spread freedom. Lowrey: “A universal, unrestricted cash benefit—just giving people money—would promote the ‘true individual freedom’ that comes from ‘economic security and independence’ as Roosevelt argued seventy years ago.” (Ibid.)

Into Reality

Most people—whatever their political leanings—can agree with the goals of ending poverty, emphasizing individual purpose in life, improving social justice for everyone, and increasing/spreading freedom. Personally, I don’t know anyone who is against these 4 things. The devil, the cliché promises, is in the details. The disagreement turns on how to accomplish such ideals. Conservatives, libertarians, liberals and progressives, not to mention socialists, anarchists, communists, mercantilists, humanists, distributists, originalists and Keynesians have long pointed out the flaws in each others’ proposals. How indeed can such goals be realized? Or, as Nietszche often quipped: “How now?”

Most people—whatever their political leanings—can agree with the goals of ending poverty, emphasizing individual purpose in life, improving social justice for everyone, and increasing/spreading freedom. Personally, I don’t know anyone who is against these 4 things. The devil, the cliché promises, is in the details. The disagreement turns on how to accomplish such ideals. Conservatives, libertarians, liberals and progressives, not to mention socialists, anarchists, communists, mercantilists, humanists, distributists, originalists and Keynesians have long pointed out the flaws in each others’ proposals. How indeed can such goals be realized? Or, as Nietszche often quipped: “How now?”

It’s one thing to have a dream; quite another to implement it effectively—in a way that both works and lasts. Lowrey, fortunately, gives us specifics: She wrote: “Providing a $1,000-a-month UBI to every American citizen would mean spending something like an additional $3.9 trillion a year. This is equivalent to a fifth of the American economy—and equal to every penny the federal government currently spends, on everything from building bridges to fighting wars to caring for the elderly to prosecuting crimes to protecting wetlands.” (Ibid.)

The obvious first question is: Who’s going to pay for this? Lowry: “The top 1 percent of earners pay about 40 percent of all income taxes, which comes to about $600 billion a year. You could tax away every penny they earned, and it would still not come close to paying for a full-fat UBI in other words.” (Ibid.)

Not a good start. But, Lowrey points out: “Eliminating or trimming back other programs would help defray the expense. Right now, the government spends roughly $2.7 trillion on its social-insurance programs…. Still, a $1,000-a-month benefit, or a smaller one, would require new spending and likely new sources of revenue, regardless of how deep other budgets were cut…. Giving the same thing to everyone means spreading the butter a lot thinner, meaning that we need more butter.” (Ibid.)

She identifies some of the major criticisms of a UBI, but suggests that “the knee-jerk opposition to some form of a UBI—crying that it is too expensive or unrealistic—feels over-wrought. Raising enough revenue for a $1,000-a-month UBI is more a matter of will than of mathematics, and would bring the United States’ tax burden in line with that of the European social democracies…. Creating a top tax bracket at 55 percent, instituting a modest wealth tax, ending the mortgage interest deduction, implementing a value-added tax—proposals like those would get us there.” (Ibid.) She further argues that since the U.S. government prints its own money, “dollars are not something the United States government can run out of.” (Ibid.) [Editor coughs and sputters…]

Lowrey is quick to add that the government shouldn’t print so much money as to cause rampant inflation, but still, she maintains, government debts, deficits, and a bit of inflation aren’t the worst things in the world. A UBI is worth it, she seems to suggest. But her easy approach to the math is…well…you decide: “A financial transactions tax would raise an estimated $100 billion to $400 billion a year. A value-added tax could easily raise a trillion dollars. A well-designed carbon tax would raise about $100 billion a year. Moreover, a wealth tax, such as a hefty levy on estates over $3 million, could raise hundreds of billions.” (Ibid.) Taxes on robots are also a possibility, Lowrey suggests, as are Negative Income Taxes where the IRS sends monthly checks to everyone below the poverty level. (Ibid.)

Where? How?

On a personal level, I was very excited to read the section on “how” to fund a UBI. After reading over three-fourths of the book and its very interesting examples and ideas about UBI economics, I was thrilled to finally get to the nitty-gritty of the plan. The finances. But…it never came. The paragraph above was as close as it got. Granted, these are interesting ideas about funding a UBI, but there is no actual detailed proposal in this book. Disappointing, to say the least.

On a personal level, I was very excited to read the section on “how” to fund a UBI. After reading over three-fourths of the book and its very interesting examples and ideas about UBI economics, I was thrilled to finally get to the nitty-gritty of the plan. The finances. But…it never came. The paragraph above was as close as it got. Granted, these are interesting ideas about funding a UBI, but there is no actual detailed proposal in this book. Disappointing, to say the least.

In fairness, perhaps a specific plan for a UBI wasn’t Lowrey’s point—such a plan might detract from her real goal, which was to promote the idea of implementing a UBI. The plan can come later. Or, possibly, she has such a plan but felt that this book should emphasize the benefits of the idea, not get people caught up in the details of just one way to do this. Wise choice, perhaps.

Still, without a specific plan, without real numbers, how can we assess the efficacy of pursuing a UBI? “We have to try” simply isn’t good enough. Especially when the numbers are so fuzzy. For example, a carbon tax might “raise about a $100 billion a year”, but how would the same tax reduce revenues from other segments of the economy—with profits impacted by energy prices? Increased fuel prices caused by such a tax would impact almost every sector of the economy. And, yes, a “value-added tax” might “easily raise a trillion dollars”, but this is a gross total, not net. The impact would be huge, and not all for good.

Likewise, even if everything Lowrey says about increased taxes is true, what is the net impact of “[c]reating a top tax bracket at 55 percent, instituting a modest wealth tax, ending the mortgage interest deduction,” etc.? What, precisely, is a “modest wealth tax”? Modest by what standard? And how does such a tax impact charities, philanthropies, and those who receive inheritances? True, Lowrey’s point is that there are ways to increase taxes—and thereby pay for a UBI—but she says little about how such increases will redirect and redistribute money. Or even if any (or all) of these increases will boost or weaken the overall economy. If GDP actually declines, the source of UBI funding will dry up, or at least diminish—while the amount required to send out $1,000-per-month naturally goes up with population.

For the Future

I actually really like Give People Money—it is well-written, enjoyable to read, full of interesting stories – sometimes fascinating, always thought-provoking. The research and quotes are excellent. Any book that features George Jetson in the same sentence as Marie Curie has my attention. By the way, I spent three very enjoyable hours just reading the endnotes and looking up articles and sources that sparked my interest. Fascinating! I’m a Lowrey fan.

I actually really like Give People Money—it is well-written, enjoyable to read, full of interesting stories – sometimes fascinating, always thought-provoking. The research and quotes are excellent. Any book that features George Jetson in the same sentence as Marie Curie has my attention. By the way, I spent three very enjoyable hours just reading the endnotes and looking up articles and sources that sparked my interest. Fascinating! I’m a Lowrey fan.

In short, I recommend the book. It’s a great read, a fun trip into economic comparisons—from Keynes to Hunger Games to Maslow’s hierarchy to Ford trucks, AI and Silicon Valley. But I didn’t come away from it with any sense that a UBI is realistic. Intriguing, yes. Thought-provoking, yes. Realistic, no. Fundable, possibly—in the short term; but what about the lasting impact?

There is another proposal of this type that is worth considering. Charles Murray has suggested that every adult receive $10,000 per year and that all other welfare-state programs be discontinued. (See In Our Hands; see also “A Guaranteed Income for Every American,” Wall Street Journal) This would cost taxpayers less than the current safety net, some argue, and it would put decisions in the hands of the actual people. Clearly a lot of government waste and misuse of funds would also be eliminated.

The key to this proposal is that it would end all other government social-insurance programs, departments, polices and expenses. Interestingly, most of the criticism against Murray’s plan, nearly all from liberals and the Left, emphasizes that it is financially infeasible. According to Murray’s own numbers, there is a $355 billion shortfall the first year. (Ibid.)

Murray suggests that the gap would be closed, eventually, as the population rises with upcoming generations. Still, the transition costs of, at least for a time, funding both the Social Security/Medicare/Medicaid model and also $10K a year to adults make the program unrealistic—as Murray himself says. But if we continue with our current system, he argues, it’s going to financially collapse anyway—better to get the ball rolling on a system that eventually will work.

Part III

“Arrival of the Fittest”

—Chevrolet/Corvette ad

“How to lead experiments that actually work”.

—Harvard Business Review

From the Starting Point

But here’s the real challenge—for all UBI-style proposals, from Lowrey to Hayek to Murray. Would a Universal Basic Income even be good for people? Is it compatible with human society and culture, human needs, human potential?

But here’s the real challenge—for all UBI-style proposals, from Lowrey to Hayek to Murray. Would a Universal Basic Income even be good for people? Is it compatible with human society and culture, human needs, human potential?

This is a big question. The most important question. At first blush, most people would like a check for $1,000 a month. Why not? A number of people could desperately use it. But what is not seen in this arrangement? Such a challenging question demands that we address what Aristotle called first things, or primary goods. First principles. The most basic foundations of human understanding are indeed vitally important, and take us back to the poignant question asked by philosophers, prophets, economists and political sages:

To be human is to ______________. ???

The word we use to fill in the blank tells us a great deal about how we view the world. The original liberal answer, articulated most clearly by thinkers like Hobbes and Rousseau, was: To be human is to suffer. In contrast, the conservative answer, from Aristotle to Adam Smith, was: To be human is to struggle.

There are, of course, other views. Shakespeare suggested that To be human is to err, The Romantics answered that To be human is to love, and the German Trifecta of Hegel, Marx and Nietszche argued that To be human is to fight and win—emphasis on win. But the initial debate between suffer and struggle remains at the center of today’s great conversation.

See Both Sides

The first approach makes the following case:

- human life is suffering

- it is up to all of us to lessen suffering as much as possible

- to do this, we need a great deal of power

- government is the entity most likely to obtain and use power in a way that greatly lessens human suffering in the world

- we should actively help grow the power and reach of government everywhere

In short: Liberalism.

The second view takes a different tack:

- the purpose of life is to struggle against all odds for goodness, righteousness, and progress

- this is best done by individuals alone and individuals voluntarily working in groups

- institutions that help individuals in this process are useful, but institutions must be carefully watched and limited because they frequently become distractions or even roadblocks to real progress

- ultimately the great, noble struggle of humans on this earth is threefold—to serve and help others in this life, to improve oneself in ways that make the world better, and in doing these first two things to prepare for better things in the life to come

To wit: Conservatism.

Richard Weaver argued that while the Progressive path tries to make life easier for everyone and institutionalize it for all, Conservatism programs attempts to help everyone more bravely and effectively embrace the path of hard things. (See Ideas Have Consequences). He taught that programs designed mainly to spread ease, especially forced attempts by government, were beneath the dignity and potential of mankind.

Today’s Goal

Weaver wrote of modern efforts to make everything easier for everyone, calling out people for promoting a life based on “Loving comfort, risking little, terrified by the thought of change…” He called this the “spoiled child psychology”, exhibited by too many adults in the modern world. The best, and worst, example of this, he said, is the widespread sense of entitlement among so many modern citizens.

Weaver wrote of modern efforts to make everything easier for everyone, calling out people for promoting a life based on “Loving comfort, risking little, terrified by the thought of change…” He called this the “spoiled child psychology”, exhibited by too many adults in the modern world. The best, and worst, example of this, he said, is the widespread sense of entitlement among so many modern citizens.

He spoke most forcefully against those who discourage lives of strenuous work, facing and overcoming challenges, struggling-failing-and-continuing-to-struggle. Such work, hard and continuous, is what life is about, Weaver taught. It is why we were born. To do things. Hard things. Alone. Together. Because work matters. And because lives of work and struggle are dignified, meaningful, and very often happy lives. We were not, he assures us, born to bask in lives of ease provided by bureaucrats or aristocrats or anyone else. Such a path he considered worthless.

These are, ironically, hard words—especially to modern ears. “Like Macbeth,” Weaver wrote, “Western man made an evil decision, which has become the efficient and final cause of other evil decisions. Have we forgotten our encounter with the witches on the heath? It occurred in the late fourteenth century, and what the witches said…was that man could realize himself more fully if he would abandon his belief in the existence of transcendentals.” (Ibid.) The witches’ solution: Stop seeing life as the battle to seek heaven, and start fixing this earth, through manmade institutions and government power. (Ibid.)

The result of this shift, from “embracing a life of struggle” to “a life of suffering and trying to institutionally force the end of suffering”, began our journey to what Weaver terms “modern decadence”. (Ibid.) In the drive to avoid and forcefully eliminate all suffering, to find the easy way and help our children seek even easier ways, most people turned to materialism. Away from service, and more to amassing money and things—as hedges against potential suffering. As Weaver put it: “Man created in the divine image, the protagonist of a great drama in which his soul was at stake, was replaced by man the wealth-seeking and-consuming animal.” (Ibid.)

It turns out that while a belief in struggle led many people to work and serve humanity, a greater faith in suffering drives most toward materialism. Ironic. An even deeper irony followed: the philosophy of suffering as the great evil spawned a culture of seeking ease through material success, and this in turn created a focus on ease itself. The work motivated by materialism gave way to the work of finding ways to avoid work. Profound. In Weaver’s words: “a carnival of specialism, professionalism, and vocationalism…fostered and protected…strange bureaucratic devices.” (Ibid.) The new mantra: government must make things easier for everyone.

Shifting

Is it any surprise that today’s generation of youth—considered by many an embodiment of a sixth human sense of entitlement—are often referred to as Snowflakes? “We should be taken care of by the government” is a popular view. “Or if not by government, then by somebody. Anybody…”

Is it any surprise that today’s generation of youth—considered by many an embodiment of a sixth human sense of entitlement—are often referred to as Snowflakes? “We should be taken care of by the government” is a popular view. “Or if not by government, then by somebody. Anybody…”

“Otherwise, how will our lives be easy?”

In reality, this view extends far beyond any one generation. Weaver said modern society is replacing homo sapiens with homo faber—meaning from “wise humans” to “humans engineered by architects, by experts”. (Ibid.) From freemen to slaves. Weaver’s connection of “the easy life” to “slavery” is interesting. Certainly a life in slavery is not easy, but only those who engage the true struggle of life can remain truly free. And the struggle is hard, not easy. Period. Those who seek lives of ease unwittingly take the path toward slavery.

As conservatives know: “If it is easy, beware…” In most cases, Easy Education, Easy Citizenship, Easy Career = Mediocre Education, Government by Elites, Middling Income. What, then, would Weaver say of a Universal Basic Income?

He wrote:

“The egotism of work increasingly poses the problem of what source will procure sufficient discipline to hold men to production. When each becomes his own taskmaster and regards work as a curse which he endures only to gain means of subsistence, will he not constantly seek to avoid it?” (Ibid.)

And what will such a man or woman do when money arrives each month and no work is required?

A few people, when work is no longer asked of them, will turn their efforts to service, art, or other areas of interest. Some will follow a great passion or goal they’ve long wanted to pursue. But what actually happens is well documented. The majority of people, when suddenly retired, laid off, recipients of the lottery, or otherwise released from daily work, struggle to fill their time with things that bring happiness. Note that this is the wrong kind of struggle.

Many such people soon find their newfound free time “accompanied by intensive explorations of the individual consciousness, with self-laceration and self-pity.” (Ibid.) They frequently turn “inward and there discover…an appalling well of melancholy and unhappiness…” (Ibid.) Weaver used these words to describe certain writers who embodied this view; but if Weaver’s words are a bit too flowery, they aren’t inaccurate. Many people find retirement, unemployment, or just lots of free time unsatisfactory and frustrating.

Reaching for Greatness

A 2015 report in The Atlantic noted: “The jobless don’t spend their time socializing or taking up new hobbies. Instead, they watch TV or sleep…. Two of the most common side effects of unemployment are loneliness, on the individual level, and the hollowing-out of community pride.” (Derek Thompson, “A World Without Work”)

A 2015 report in The Atlantic noted: “The jobless don’t spend their time socializing or taking up new hobbies. Instead, they watch TV or sleep…. Two of the most common side effects of unemployment are loneliness, on the individual level, and the hollowing-out of community pride.” (Derek Thompson, “A World Without Work”)

For many people, it turns out that “easy” is unfulfilling, in the same way that achieving something hard is one of the most rewarding things human beings ever experience. Words such as victory, accomplishment, triumph, success, progress, improvement, and even happiness, defy definition and mean very little unless they are preceded by difficulty and hard work. The greater the struggle, in fact, the greater the victory. Thomas Paine made this a central theme in his writings.

The truth is that the reality flies in the face of modern thinking. Specifically, most people want hard, even if they don’t realize it. Without hard, most people simply aren’t happy. It turns out that hard isn’t always equal to suffering, but it is in fact a vital component of happy. “Easy” is nice as a vacation, but it isn’t the basis of a good life. “Hard” can be such a basis, as long as it is accompanied by freedom—or at least the opportunity to gain freedom.

As for a Universal Basic Income, the jury is still out. If people don’t have to work for their basic living, some will argue, they’ll work for other things—better things. This is certainly true of some people, and it may be true for many more. That said: It is definitely not true of everyone. Whether it is true for enough people to make it worth adopting as public policy will likely be debated for many years to come. But the promise of a UBI, that it will significantly reduce human suffering, naturally sounds good to many moderns but sparks immediate skepticism in those who embrace the historical reality of human nature. Humanity has proven, many times, that hard challenges, within reason, are nearly always better for people than lasting times of ease.

I have my doubts that a UBI will do much to fix the actual problem. It could easily do the opposite: when a lot more people aren’t working, some of them might use their time in ways that hurt others and increase suffering. This is certainly a possibility.

Pushing Riding Forward

Modern man, Weaver pointed out, has: “been given the notion that progress is automatic” that he/she has not just a right to pursue happiness but “a right to have happiness”, regardless of what he does, or doesn’t do. (Ideas Have Consequences) He has been told that someone else is responsible for his happiness, and that if he is sad, or unfulfilled, someone else is to blame. (Ibid.) He has been informed that if he feels frustration, some superior “in the hierarchy” has “practiced an imposition upon him”. (Ibid.)

Modern man, Weaver pointed out, has: “been given the notion that progress is automatic” that he/she has not just a right to pursue happiness but “a right to have happiness”, regardless of what he does, or doesn’t do. (Ideas Have Consequences) He has been told that someone else is responsible for his happiness, and that if he is sad, or unfulfilled, someone else is to blame. (Ibid.) He has been informed that if he feels frustration, some superior “in the hierarchy” has “practiced an imposition upon him”. (Ibid.)

“The truth is,” Weaver said, “that he has never been brought to see what it is to be a man…. [T]hat he really owes thanks for the pulling and tugging that allow him to grow…. This citizen is now the child of indulgent parents who pamper his appetites and inflate his egotism until he is unfitted for struggle of any kind.” (Ibid.) And the following zinger:

“The spoiling of man seems always to begin when urban living predominates over rural.” (Ibid.)

Is it lost on anyone that this is directly related to Blue State/Red State culture?

“In effect,” Weaver continues, “what modern man is being told is that the world owes him a living. He assents the more readily for being told in a roundabout way, which is that science owes him a living.” (Ibid.) “An artificial environment causes him to lose sight of the great system not subject to man’s control.” (Ibid.) Indeed, his moral and ethical senses are shaped by newspapers more than prayers, to paraphrase Nietszche.

What does that “great system” say about work? Easy versus hard? Individual responsibility versus institutions? If we push aside the culture of newspapers and instant mobile news updates for a moment, and instead ask the kind of questions obvious in a culture based on the idea that “humans thrive in the hard struggle,” we find ourselves dealing with bigger issues:

- Is pay without work good for the soul?

- Is it good for family life, or is it more likely to hurt families?

- Will it naturally render adults more child-like, dependent?

- And, since the pay actually comes from the work of someone else, are we simply taking from their work and accepting it without recompense?

- What does the fact that they are forced to pay this money say about those who accept it?

- Can a people remain free under such an arrangement?

Building or Breaking

These are big questions. Unlike most modern policy debates, these big questions ignore the small talk and get to the real point. For some, this is distracting. “That’s not how it’s done,” scolds many a modern expert. But the truth is still relevant, right? Big realities do matter.

These are big questions. Unlike most modern policy debates, these big questions ignore the small talk and get to the real point. For some, this is distracting. “That’s not how it’s done,” scolds many a modern expert. But the truth is still relevant, right? Big realities do matter.

The view of human life as a great struggle for goodness puts each citizen forward as a potential hero. But the hero’s currency, Weaver notes, is “exertion, self-denial, endurance”, while “the spoiled child” wants everyone to be protected from hard things—especially making a living. (Ibid.) Preferably, in this latter view, such protection will come from government—the regime as supreme being, the end-all of suffering, the all-powerful state.

To be clear, a society of people who seek $1,000 (or other) payments from the government, not for work but just because they need or want it, is not on a path to freedom—or even to maintaining the freedoms they already enjoy. Speaking of payments from the government, the following story is related by Weaver in Ideas Have Consequences:

“During the early part of the second World War there came to light the story of a farmer from the back country of Oklahoma—one of the yet unspoiled—who, upon hearing of the attack on Pearl Harbor, departed with his wife to the West Coast to work in the shipyards…. [T]he new worker did not understand the meaning of the little slip of paper handed him once a week. It was not until he had accumulated over a thousand dollars in checks that he found out that he was being paid to save his country. He had assumed that when the country is in danger, everyone helps out, and helping out means giving.”

The Spiral

Also from Weaver:

“The past shows unvaryingly that when a people’s freedom disappears, it goes not with a bang, but in silence amid the comfort of being cared for…. If freedom is not found accompanied by a willingness to resist, and to reject favors [from the government], it will not long be found at all.”

Easy kills.

Hard is the future.

But those on the side of freedom embrace the struggle.

This is hard doctrine, no doubt. But it is the doctrine of a free people, and those who would remain free. Those seeking the way of ease will not, by definition, choose freedom—or fight for it when needed. Freedom is hard. Those searching for ever-easier paths will vote for more government, and when unearned $1,000 checks arrive each month to reward their search, a majority will do what makes the most sense in such a situation: vote for candidates who promise to increase the checks to $1,200 then $1,500 then $2,100…and more. Government will increasingly apply more force to the productive individuals and organizations in society, and everyone else as well.

No free society can weather—financially, politically, or morally—such an electorate.

Ever.

“Freedom is a fragile thing and is never more than one generation away from extinction. It is not ours by inheritance; it must be fought for and defended constantly by each generation, for it comes only once to a people. Those who have known freedom and then lost it have never known it again.”

—Ronald Reagan

Suggested Readings

- An important article that addresses the future of work, a basic universal income, and recent trends in technology and employment—Derek Thompson, “A World Without Work,” The Atlantic, July/August 2015

- Daniel Pink, A Whole New Mind

- Joshua Cooper Ramo, Seventh Sense

- Virgil, Georgics

- Victor Davis Hansen, The Other Greeks

Category : Blog &Book Reviews &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Generations &Government &History &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Politics &Service &Statesmanship

A Truly Great New Book on Education

August 6th, 2016 // 1:33 pm @ Oliver DeMille

(A Review of Passion-Driven Education by Connor Boyack)

(A Review of Passion-Driven Education by Connor Boyack)

I have seen the future, and it is encapsulated in a new book: Passion-Driven Education by Connor Boyack. It will forever change how you think about your children’s education—and your own.

Okay, it doesn’t actually show us the future. But Passion-Driven Education is a masterpiece. It’s an idea whose time has definitely arrived.

The Past

Here’s how we got to this point. The old-style education of the 1950s through 2000s was based on rote memorization, multiple-choice standardized exams, bureaucratic presidential reports and programs like A Nation at Risk, No Child Left Behind, and Common Core, and a “big-business” educational mentality that focused on curriculum design (usually one-size-fits-all), teacher training, construction of school buildings, administrative budgets (sometimes increases, other years cuts), and a lot of politics thrown into the mix.

The educational bureaucracy managed to get its fingers into almost everything about education, except actually helping students learn—more effectively, with higher quality and true one-on-one help and individualized learning. A lot of teachers did the unheralded work of quality mentoring, but a majority of students fell through the cracks. Indeed, the emphasis was always on schooling, funding, and educating, while personal student learning was seldom a priority.

And great education was hardly ever mentioned. Mediocrity reigned.

The Present