Education Exposed

October 28th, 2014 // 3:24 pm @ Oliver DeMille

Hire and Higher and Hire

Just read the following quote. It is incredibly powerful:

Just read the following quote. It is incredibly powerful:

“Universities…have been absorbed into the commercial ethos. Instead of being intervals of freedom, they are breeding grounds for advancement. Students are too busy jumping through the next hurdle in the résumé race to figure out what they really want…. They have been inculcated with a lust for prestige and a fear of doing things that might put their status at risk. The system educates them to be excellent, but excellent sheep.”

This is a profound and all too accurate description of our current educational system. It was written in the New York Times by David Brooks, as a summary of a William Deresiewicz’s essay in his book Excellent Sheep.

Let’s briefly consider each main point:

- “Universities…have been absorbed into the commercial ethos. Instead of being intervals of freedom, they are breeding grounds for advancement.”

This is true of schools in general today, at all levels. Most people now see the goal of almost all schools as job preparation, as Hire Education instead of Higher Education.

In this model, the quality of learning isn’t important. Job placement is the goal, and it drives the whole educational system.

Moving Backwards

Sadly, it drives it down, not up. As the quality of education decreases, so does the quality (and availability) of jobs for most people.

- “They have been inculcated with a lust for prestige and a fear of doing things that might put their status at risk.”

The conveyor-belt approach to learning trains followers, not leaders. It makes our students and workers risk averse, not creative or entrepreneurial. Our economy is losing jobs by the thousands to nations where initiative, ingenuity, and innovation are rising. In these vital things, our failure rates are growing.

- “The system educates them to be excellent, but excellent sheep.”

Our education system of “students follow, while their superiors tell them what and when to do things—from Kindergarten through graduate school” is creating a populace that obediently takes its marching orders from the media, experts, and government officials. But free societies only stay free when the people are watching things and telling the officials and experts what to do.

We’ve got it backwards. Most of our current educational system is designed for a socialist nation, not for a free one.

Leaders or Drones

There is a solution, and it is for parents and teachers to deliver Leadership Education and teach young people how to think—not what to think.

This has been the focus of our work with TJEd (Thomas Jefferson Education) for over two decades. It’s tenets are simple: classics rather than rote textbooks, mentors rather than professors, personalized learning rather than the conveyor belt, quality rather than conformity, etc.

It all boils down to inspiring students to passionately choose the work of getting a great education, not requiring youth to do the rote behaviors of mediocre learning—or even the rote actions that bring high test scores but turn students into excellent sheep.

In The Atlantic, Sandra Tsing Loh called this “high-class drone work.” Note that she was referring to the prestigious but rote careers that such education leads to, not to the schooling.

Leadership Education is a better way. For everyone.

Simplicity and Success

Just consider another powerful quote, this one from Luba Vangelova writing about the non-traditional revolution in modern education:

“Every day, veteran educator Scott Henstrand walks into his history classroom at the Brooklyn Collaborative secondary school, jots down a few conversation-starters on the blackboard, then takes a seat amongst the 14- to 17-year-olds. He does the same work as they do, and raises his hand when he wants to speak.”

This sounds like a formal school modeled after an excellent Leadership Education homeschool:

- “Inspire, not Require.”

- “Simplicity, not Complexity.”

- “You, not Them.”

- Mixed ages.

- A mentor learning right along with the students.

- Readings and lots of discussions.

Great education is really quite simple, after all, as successful homeschoolers can attest.

For help in engaging your education, and mentoring others in their learning, join us for Mentoring in the Classics >>

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Among many other works, he is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, The Coming Aristocracy, and FreedomShift: 3 Choices to Reclaim America’s Destiny.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah

Category : Blog &Community &Culture &Current Events &Education &Family &Featured &Generations &Leadership &Liberty &Mini-Factories &Mission

The New Ivy League by Oliver DeMille

August 27th, 2014 // 6:34 am @ Oliver DeMille

The Dinosaur Reality

The day of turning a college degree into a ready job and high pay is over. That was then. The new economy is different now, and many graduate schools are taking note.

For example, The New York Times reported:

“On a spring afternoon at Michigan State University, 15 law students are presenting start-up proposals to a panel of legal scholars and entrepreneurs and an audience of fellow students. The end-of-the semester event is one part seminar and one part ‘Shark Tank’ reality show.

“The companies the students are describing would be very different from the mega-firms that many law students have traditionally aspired to work for, and to grow wealthy from. Instead, these young people are proposing businesses more nimble and offbeat: small, quick mammals [entrepreneurial businesses] scrambling underfoot in the land of dinosaurs [oldstyle mega-businesses].” (John Schwartz, “This is Law School?” The New York Times, August 1, 2014)

Many schools are increasingly emphasizing entrepreneurialism in a new economy where the traditionally educated law school graduate faces a dearth of jobs. “With the marketplace shifting, schools have increasingly come under fire for being out of touch.” (ibid.)

Professionals in the Basement

A surprisingly high number of law school and other professional school graduates are moving back home to live with parents, and those who do get jobs are finding the work stifling and unrewarding in an environment with a glut of professionals holding degrees.

Those who don’t like the cutthroat and grinding work are easily replaced.

In fact, a Forbes study recently noted that being an associate attorney is the least happy job in the nation. (See Psychology Today, July 2014) It has relatively high pay compared to most entry-level career paths, but the hours are extreme and the other rewards are minimal.

With the glut of attorneys in the market, a large number of law school grads are ending up as paralegals anyway—which seldom helps them to pay off their huge student loans. (ibid.) Medical careers are nearly as bad for most young people—at least for the first eight to twelve years.

A recent poll of college graduates showed:

“People who take out significant college loans score worse on quality-of-life measures, a trend that persists into middle age…. Even 24 years after graduation, students who borrowed more than $25,000 are less likely to enjoy work and are less financially and physically fit than their counterparts who graduated without debt.

For more recent college grads, the discrepancy is even more pronounced….

“About 70% of college grads have debt (Douglas Belkin, “Heavily Indebted Grads Rank Low on Life Quality, The Wall Street Journal, August 8, 2014), and those with graduate or professional schooling have even more debt on average than those with a four-year degree.

“Catherine L. Carpenter, vice dean of Southwestern Law School in Los Angeles, tracks curriculum across the country. She said schools are trying to teach their students to run their own firms, to look for entrepreneurial opportunities by finding ‘gaps in the law or gaps in the delivery of services,’ and to gain specialized knowledge that can help them counsel entrepreneurs.” (op cit. Shwartz)

A Return to Apprenticeship

Some of the schools themselves are turning more entrepreneurial as well. The Times reported:

“All law schools, including the elites, are increasing skills training by adding clinics and externships…. [T]he University of Virginia will allow students to earn a semester of credit while working full time for nonprofit or government employers anywhere in the world.” (Ethan Bronner, “To Place Graduates, Law Schools Are Opening Firms,” The New York Times, March 7, 2013)

This kind of non-traditional learning harks back to the time when most attorneys learned by apprenticing with practicing lawyers—usually with no formal law school at all.

A few law schools are also implementing innovative ways to help their graduates get jobs, or work in firms set up specifically for this purpose by the law schools. For example, Arizona State University set up a special nonprofit law firm so that some of its graduates would have a place to work and learn to practice law.

“[There is] a crisis looming over the legal profession after decades of relentless growth…. It is evident in the sharp drop in law school applications….

“[P]ost-graduate training programs appear to be the way of the future for many of the nation’s 200 law schools. The law dean of Rutgers University just announced plans for a nonprofit law firm for some of his graduates.” (ibid.)

Entrepreneurship and Life

Other innovations are trying to deal with the crisis.

“At Indiana University’s law school, Prof. William D. Henderson has been advocating a shake-up in legal education whose time may have come. ‘You have got to be in a lot of pain’ before a school will change something as tradition-bound as legal training, he said, but pain is everywhere at the moment, and ‘that’s kind of our opening.’” (op cit. Shwartz)

“‘This is the worst time in the history of legal education to go to law school,’ said Patrick Ellis, a recent graduate [of Michigan State University]. ‘I am not top of my class, not at a top-10 law school, but I’m confident I’m going to have a meaningful career because of this [entrepreneurial studies] program.’” (ibid.)

Entrepreneurialism is injecting life into many sectors of the economy. In fact, it always has. Without entrepreneurship, free economies cannot flourish. But when the economy is as sluggish as the new market today, entrepreneurs are the main hope.

Note that it’s not just law school grads who are facing a tough economy. Don Peck wrote:

“The Great Recession may be over, but this era of high joblessness is probably just beginning. Before it ends, it will likely change the life course and character of a generation of young adults…. The economy now sits in a hole 10 million jobs deep…[and] we need to produce roughly 1.5 million jobs a year—about 125,000 a month—just to keep from sinking deeper.

“Even if the economy were to immediately begin producing 600,000 jobs a month—more than double the pace of the mid-to-late 1990s, when job growth was strong—it would take roughly two years to dig ourselves out of the hole we’re in…. But the U.S. hasn’t seen that pace of sustained employment growth in more than 30 years…” (Don Peck, “Can the Middle Class Be Saved?” The Atlantic, March 2010)

In addition, to pay for college, many more students are staying home and learning in local schools or talking courses online. (See, for example, Tamar Lewin, “Colleges Adapt Online Courses to Ease Burden, The New York Times, April 29, 2013.)

And over half of college students who go away to earn their degrees have moved back home after graduation in recent years—they aren’t finding jobs, and home is their only option in many cases. (Harper’s Index, Harpers, August 2011).

Deep Holes Around the World

In fact, this problem is prevalent in Europe as well as the United States.

As one report noted:

“By the time the parents of Serena Violano were in their early 30s, they had solid jobs, their own home and two small daughters. Today, Serena, a 31-year-old law graduate, is still sharing her teenage bedroom with her older sister in the small town of Mercogliano, near Naples.” (Ilan Brat and Giada Zampano, “Young, European and Broke,” The Wall Street Journal, August 9-10, 2014)

With few jobs available in her field, she “spends her days studying for the exam to qualify as a notary in the hopes of scoring a stable job.” (ibid.)

The reason the European economies are struggling is the same as the American challenge–with one difference: the media is more open in saying what is really causing the problems in Europe.

For example, “[the young European’s] predicament is exposing a painful truth: The towering cost of labor protections that have provided a comfortable life for Europe’s baby boomers is now keeping their children from breaking in [to economic opportunity].” (ibid.)

Dead or Alive

In the United States, such protections include Social Security, Health Care laws, Government Pensions, other entitlements, and the debt necessary to maintain these programs—along with the high levels of regulation that hamper entrepreneurial ventures.

But why are people turning to graduate school to learn entrepreneurship, when the best entrepreneurs tend to learn their craft by application in the real market? It appears to be a matter of trying to avoid risk—of attempting to do what works in the new economy (entrepreneurship) while hedging one’s bets by still doing what used to work in the old economy (college degrees).

As one interesting article captured this theme: “College is Dead. Long Live College!” (Amanda Ripley, “College is Dead. Long Live College!” Time Magazine, October 18, 2012, cited in Allen Levie, “The Visual Tradition: The Coming Shift in Democracy,” unpublished manuscript.)

Both “college is dead” and “long live college” can’t technically be true at the same time, but today’s students and their parents aren’t sure which to believe. Still, the best road to entrepreneurship is clearly the path of actually engaging entrepreneurialism.

This is a scary reality for a generation that was raised to believe that school was basically the only route to career success.

Watching Results

Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in Democracy in America that as go the attorneys, so goes the United States. Today the cutting-edge trend in legal training is a huge influx of entrepreneurialism.

Ultimately, as another report put it:

“It used to be that college was the ticket to the top. Now graduates are starting from the bottom—buried by student-loan debt that has skyrocketed to a collective $1.2 trillion” in the United States. (Kayla Webley, Generation Debt, MarieClaire, June 2014) Today’s college students and graduates are coming to be known less as the Millennial Generation and more as “Generation Debt.” (ibid.)

This doesn’t mean that higher education is dead. It means that “hire education” is going to be increasingly judged by how well it works—meaning how effectively its users succeed as entrepreneurs.

As a result, a lot of “higher education” innovation and non-traditional types of learning—many of them informal, self-directed and hand-on-building-a-business—are beginning to flourish.

Those who successfully entrepreneur (in law and nearly every other sector of the economy) are going to be the successes of the future. Entrepreneurship is the new Ivy League.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Among many other works, he is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, The Coming Aristocracy, and FreedomShift: 3 Choices to Reclaim America’s Destiny.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Business &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Education &Entrepreneurship &Leadership &Mini-Factories &Mission &Producers &Prosperity &Statesmanship

A Missing Piece of Entrepreneurship

July 25th, 2014 // 7:38 am @ Oliver DeMille

What Some Entrepreneurs Are Missing

I write a lot about entrepreneurship, even though my main focus is freedom. The reason for this is simple: free nations are always nations with a strong entrepreneurial sector. There are no exceptions in history.

Put simply, the great free nations of human experience had a flourishing free enterprise. This was true in ancient Athens and ancient Israel, the Swiss free era and the Frank golden age, the free periods of the Saracens and also the Anglo-Saxons, the American founding era and the modern free nations of Britain, U.S., Canada, Japan and Europe, among others.

Take away free enterprise, and a nation’s freedom always declines. Shut down the entrepreneurial spirit, and liberty rapidly decreases.

The main reason freedom rises or falls with entrepreneurialism is simple: 1) to succeed as an entrepreneur, a person must exhibit the character traits of initiative, innovation, ingenuity, creativity, wise risk-taking, sacrifice, tenacity, frugality, resilience, and perseverance, and 2) these characteristics are precisely the things that through history have proven necessary for free citizens to stay free.

The Hidden Problem

The large majority of responses when I write about entrepreneurship are thoughtful, insightful, and even wise. But once in a while when I write an article pointing out the importance of free enterprise and entrepreneurship to freedom, I get a strange response. I call it “strange” because it shows that some people don’t quite understand what I mean by entrepreneurship. Such comments go something like this:

“I’m a born entrepreneur, and I’ve started dozens of businesses, so I understand that…”

“I have a list of ideas for successful entrepreneurial projects—could you suggest which of these might be the best options…”

“My spouse is constantly starting entrepreneurial ventures and using up our capital in such schemes, and your article made him want to do several more of them…”

These types of sentences are a real head-scratcher. Why? Because this isn’t what successful entrepreneurship and free enterprise is all about. Not at all.

Successful entrepreneurs typically start 2-4 businesses during their life, not dozens, and at least one of them becomes an important enterprise. The free market just doesn’t reward people who start dozens of businesses, frequently jumping around from business to business.

People who are constantly engaged in their latest “start-up” aren’t really following the entrepreneurial path. They’re just endlessly repeating the first part of it. Free enterprise rewards those who stick with a business until it becomes a real success, or who learn from the mistakes of the past and then stick with the next venture until it truly prospers.

A lot of successful entrepreneurs have had a failure or two, but not many of them have spent their years working on dozens of businesses. They soon learn to pick one and do what it takes to succeed. They buckle down and go through the process of turning their company into something.

In fact, many successful owners have suggested that it takes about 10,000 hours, or even more, to become good enough at a business or economic sector to make it profitable. Those who are constantly jumping around just can’t ever get there.

The Real Thing

When people talk about an entrepreneurial attitude or viewpoint of always starting another business, that’s one thing. But it’s not the same thing as tenaciously persevering until one business flourishes—and then tenaciously persevering as it keeps thriving.

This latter approach is the kind of entrepreneurship that builds a nation. It’s more than just a posture or a habit of starting a bunch of businesses. It’s more than liking the idea of business ownership. It’s more than talking about being your own boss.

It takes an amazing amount of hard work and tenacity to make a business truly work. Nothing else really gets the job done—for entrepreneurship, or for freedom.

This might seem like a little thing, like a meaningless play on words, but it isn’t. It is huge! Entrepreneurship doesn’t spur liberty in a society just because some people have an independent, “I’ll do it myself” or “I’d rather be my own boss” attitude. That’s part of it, but there’s more.

Free enterprise is great when the enterprises work. This happens only when the small business owner pays the price to become a successful leader and make the enterprise blossom and grow.

Again, this might not always occur—and it never comes easily—but the leaders who build a free nation are those who hunker down and do the hard work to make it happen. Even if they fail, they make it happen the next time. One dedicated day at a time. Through all the hard times and challenges. Even when everyone else would have given up.

A nation with a lot of such entrepreneurs has a real chance at freedom.

A nation without them never does.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Among many other works, he is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, The Coming Aristocracy, and FreedomShift: 3 Choices to Reclaim America’s Destiny.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah

Category : Blog &Business &Citizenship &Community &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Entrepreneurship &Leadership &Liberty &Mini-Factories &Producers &Prosperity

The Three Economies by Oliver DeMille

July 11th, 2014 // 9:42 am @ Oliver DeMille

The Hidden Economy

There are three economies in modern society. They all matter. But most people only know about two of them. They know the third exists, in a shadowy, behind-the-scenes way that confuses most people. But the first two economies are present, pressing, obvious. So people just focus on these two.

There are three economies in modern society. They all matter. But most people only know about two of them. They know the third exists, in a shadowy, behind-the-scenes way that confuses most people. But the first two economies are present, pressing, obvious. So people just focus on these two.

A couple of recent conversations brought these economies even more to the forefront of my thinking. First, I was meeting with an old friend, touching base about the years since we’d talked together. He mentioned that his oldest son is now in college, and how excited he is for his son’s future. I asked what he meant, and he told me an interesting story.

Over twenty years ago he ran into another of our high school friends while he was walking into his community college admin building. The two greeted each other, and they started talking. My friend told his buddy that he was there to dis-enroll from school. “I just can’t take this anymore,” he told him. “College is getting me nowhere.”

“Well, I disagree,” his buddy said. “I’m here to change my major. I’m going to get a teaching credential and teach high school. I want a steady job with good benefits.”

A Tale of Two

Fast forward almost thirty years. My friend ran into his old buddy a few weeks ago, and asked him what he’s doing. “Teaching high school,” he replied.

“Really? Well, you told me that was your plan. I guess you made it happen. How much are you making, if you don’t mind me asking?”

When his friend looked at him strangely, he laughed and said, “I only ask because you told me you wanted a steady job with good benefits, and I wanted to get out of school and get on with real life. Well, I quit school that day, but I’m still working in a dead end job. Sometimes I wonder what I’d be making if I had followed you into the admin building that day and changed majors with you.”

After a little more coaxing, the friend noted that he was making about $40,000 a year—even with tenure and almost thirty years of seniority. “But it’s steady work, like I hoped. Still, I’ve got way too much debt.”

After telling me this story, my friend looked at me with what can only be described as slightly haunted eyes. “When he told me he makes $40K a year, I just wanted to scream,” my friend said.

“Why?” I asked.

He could tell I didn’t get what he was talking about, so he sighed and looked me right in the eyes. “I’ve worked 40 to 60 hour weeks every month since I walked off that campus,” he told me. “And last year I made about $18,000 working for what amounts to less than minimum wage in a convenience store. I should have stayed in college.”

That’s the two economies. One goes to college, works mostly in white-collar settings, and makes from thirty thousand a year up to four times that. Some members of this group go on to professional training and make a bit more. The other group, the second economy, typically makes significantly less than $50,000 a year, often half or a third of this amount, and frequently wishes it had made different educational choices.

The people in these two economies look at each other strangely, a bit distrustfully, wondering what “could have been” if they’d taken the other path.

That’s the tale of two economies.

II.

Which brings me to my point. Ask members of either economy for advice about education and work, and they’ll mostly say the same thing. “Get good grades, go to college, get a good career. Use your educational years to set yourself up for a steady job with good benefits.” This is the advice my grandfather gave my father at age twenty, and the same counsel my dad gave me after high school. Millions of fathers and mothers have supplied the same recommendations over the past fifty years.

This advice makes sense if all you know are the two economies. Sadly, the third economy is seldom mentioned. It is, in fact, patently ignored. Or quickly discounted if anyone is bold enough to bring it up.

A second experience illustrates this reality. I recently visited the optometrist to get a new prescription for glasses. During the small talk, he mentioned that his younger grandchildren are in college, but scoffed that it was probably a total waste of time. “All their older siblings and cousins are college graduates,” he said, “and none of them have jobs. They’ve all had to move back home with their parents.”

He laughed, but he seemed more frustrated than amused. “It’s the current economy,” he continued. “This presidential administration has been a disaster, and it doesn’t look like anyone is going to change things anytime soon. I don’t know what these kids are supposed to do. They have good degrees—law, accounting, engineering—but they can’t find jobs. Washington has really screwed us up.”

I nodded, and brought up the third economy, though I didn’t call it that. What I actually said was: “There are lots of opportunities in entrepreneurship right now.” He looked at me like I was crazy. Like maybe I had three heads or something. He shook his head skeptically.

“Entrepreneurship is hard work,” I started to say, “but the rewards of success are high and…”

He cut me off. Not rudely, but like he hadn’t really heard me. That happens a lot when you bring up the third economy.

“No,” he assured me, “college is the best bet. There’s really no other way.”

I wasn’t in the mood to argue with him, so I let it go. But he cocked his head to one side in thought and said, slowly, “Although…” Then he shook his head like he was discounting some thought and had decided not to finish his sentence.

“What?” I asked. “You looked like you wanted to say something.”

“Well,” he paused…then sighed. I kept looking at him, waiting, so he said, “The truth is that one of my grandsons didn’t go to college.” He said it with embarrassment. “Actually, he started school, but then dropped out in his second year. We were all really worried about him.”

A “Real” Job

He paused again, and looked at me a bit strangely. I could tell he wanted to say more, but wasn’t quite sure how to go about it.

“What happened?” I prompted.

“To tell you the truth, I’m not really sure. He started a business. You know, one of those sales programs where you build a big group and they buy from you month after month. Anyway, he’s really doing well. He paid off his big house a few years ago—no more mortgage or anything. He has nice cars, all paid for. And they travel a lot, just for fun. They fly chartered, real fancy. He and his wife took us and his parents to Hawaii for a week. He didn’t even blink at the expense.”

“That’s great,” I told him. “At least some people are doing well in this economy.”

He looked at me with that strange expression again. “I’m not sure what to make of it,” he said. “I keep wondering if he’s going to finish college.”

I was surprised by this turn of thought, so I asked, “So he can get a great education, you mean? Read the classics? Broaden his thinking?”

He repeated the three heads look. “No. He reads all the time—doesn’t need college for that. I want him to go back to college so he can get a real job.”

I laughed out loud. A deep belly laugh, it was so funny. I didn’t mean to, and I immediately worried that I would offend him, but he grinned. Then he shook his head. “I know it’s crazy, but I just keep worrying about him even though he’s the only one in the family who is really doing well. The others are struggling, all moved back in with their parents—spouses and little kids all in tow. But they have college degrees, so I keep thinking they’ll be fine. But they’re not. They’re drowning in student debts and a bunch of other debts. It just makes no sense.”

America Needs to Get It

He sighed and talked bad about Washington again. Finally he said, “I’ve poured so much money into helping those kids go to college, and now the only one who has any money to raise his family is the one who dropped out. It just doesn’t make any sense.” He kept shaking his head, brow deeply furrowed.

I left his office thinking that he’s so steeped in the two economies he just doesn’t really believe the third economy exists. He just doesn’t buy it, even when all the evidence is right there in front of him.

He’s not alone. The whole nation—most of today’s industrialized nations, in fact—are right there with him. We believe in the two economies, high school/blue collar jobs on the one hand, and college/white collar careers on the other. Most people just never quite accept that the entrepreneurial economy is real.

It’s too bad, because that’s where nearly all the current top career and financial opportunities are found. The future is in the third economy, for those who realize it and get to work. If you’ve got kids, I hope you can see the third economy—for their sake. Because it’s real, and it’s here to stay.

The first two economies are in major decline, whatever the so-called experts claim. Alvin Toffler warned us in his bestseller FutureShock that this was going to happen, and so did Peter Drucker, back when they first predicted the Information Age. Now it’s happening.

I hope more of us realize the truth before it’s too late. Because China gets it. So does India, and a bunch of other nations. The longer we take to get real and start leading in the entrepreneurial/innovative economy (the real economy, actually), the harder it will be for our kids and grandkids. The third economy will dominate the twenty-first century. It already is, in fact. Whether we’ve chosen to see it yet or not.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Among many other works, he is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, The Coming Aristocracy, and FreedomShift: 3 Choices to Reclaim America’s Destiny.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah

Category : Blog &Business &Citizenship &Community &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Education &Entrepreneurship &Generations &Leadership &Mini-Factories &Statesmanship

Were the Founders Lawyers or Entrepreneurs? A Surprising Answer

July 1st, 2014 // 12:47 am @ Oliver DeMille

A Difference Changes Everything

“You frequently mention that free nations have a lot of entrepreneurs,” my friend said, “but I’ve been studying the American Founding era and it turns out that many of the framers were lawyers. Why don’t you tell people that a lot more of us should go into law?”

“You frequently mention that free nations have a lot of entrepreneurs,” my friend said, “but I’ve been studying the American Founding era and it turns out that many of the framers were lawyers. Why don’t you tell people that a lot more of us should go into law?”

It was a good question, so I nodded my head. “You’re right, but there is one big difference between law at the time of the founding and law today. The difference is so big, in fact, that it changes everything. Well, maybe not everything. But it changes the whole way law and freedom interact.”

I cocked my head to one side. “Actually, another friend of mine recently sent me a note about the same thing. He had always thought that most of the framers were merchants or farmers, but he was surprised to find out how many of them were lawyers. As much as I’ve said about the value of entrepreneurs to freedom, I guess I better mention how the legal profession fits.”

“I agree,” he responded. “If the founders are a good example of a generation that increased freedom, why wouldn’t we just emulate them on this?”

“I wish we could,” I told him. “But it’s illegal.”

Lawyers and Laws

He laughed…but when he noticed that I wasn’t laughing he stopped. “You’re not joking?”

“No, I’m not. It’s illegal be the kind of lawyer that many of the framers were. That’s the big difference I was telling you about.”

He looked really interested, so I continued.

“Let me ask you a question,” I began. “What would happen if you read a bunch of history, legal books, judicial decisions in court cases, and important government documents, and then decided to put a sign on the front of your house with your name, followed by “Attorney at Law”? You do this without attending law school, just lots of hard study and a good understanding of law and freedom, and you start marketing for clients?”

“Uh, I’d be in trouble,” he retorted. “You have to have a license to practice law. Go before the Bar, get state approval, and all that. And you have to graduate from law school in order to do this. I looked into it years ago when I was making career decisions.”

“So you have to graduate from a state-approved law school, right?”

“Of course.”

“Is that what the framers did to become lawyers?” I asked.

“I’m not sure. Some did, I think. Like Jefferson. Though I remember reading that Patrick Henry took the Bar without law school. Come to think of it, so did Jefferson. He studied law with mentors, but not at an official law school. Same with…well, a lot of the framers. Law schools didn’t come until later.”

“That’s the difference,” I told him. “In the founding era, depending on the colony, you could read and take the bar, or work as an apprentice, or read under the tutelage of a mentor, or in most of early American history and our Westward expansion a person could just practice law by hanging out a shingle and taking on clients. In our day, you have to graduate from a state approved law school and then get personal state approval in the form of a license. It’s a totally different process.”

Goal and Outcome

“Are you saying the way we do it now is worse?” he asked.

“That depends on how you are measuring it. A lot of people will say that the type of training students get in modern law schools is much better than when early lawyers just read a lot of books and cases. They’ll say that the modern methods turn out much better professionals than the old way ever could.

“And, honestly,” I continued, “this argument has merit. But only if the goal is professionalism and maintenance of the legal profession. In the founding era, the goal was different.”

“What was it?”

“It was to check the government. Think about it: When law schools have to be approved by the government, and the accreditation agencies for law schools have to be approved by the government, and all licensing for attorneys is overseen by the government, the attorneys are bound—at some level—by the government. The government can take away their licensing and their livelihood at any time, so lawyers are bound to do things in the approved and accepted ways. They can check the government only in ways the government allows.

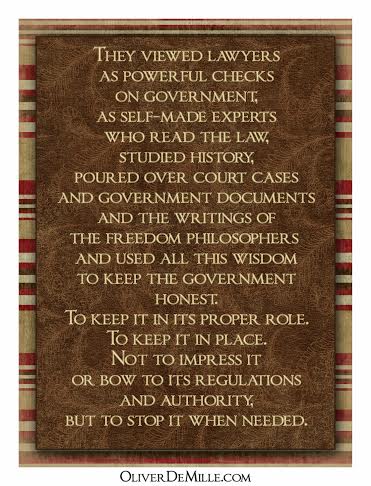

“You can argue that this is a good system, or not. But it is very different from how the founders saw it. They viewed lawyers as powerful checks on government, as self-made experts who read the law, studied history, pored over court cases and government documents and the writings of the freedom philosophers—and used all this wisdom to keep the government honest. To keep it in its proper role. To keep it in place. Not to impress it or bow to its regulations and authority, but to stop it when needed.

A Broken Check

“But if the government licenses lawyers and every step of becoming lawyers, they can’t really go around checking the government at every turn. At least not at the same level as if they are truly independent. For example, when Edmund Burke wanted to warn the British Parliament against going to war against the American colonies on March 22, 1775, he told them they should avoid such a war because so many Americans were students of the law.”

I then shared Burke’s words when he said:

Permit me, Sir, to add another circumstance in our colonies, which contributes no [small] part towards the growth and effect of this untractable spirit. I mean their education. In no country perhaps in the world is the law so general a study…. [A]ll who read, and most do read, endeavor to obtain some smattering in that science. I have been told by many an eminent bookseller, that in no branch of his business, after tracts of popular devotion, were so many books as those on the law exported…. The colonists have now fallen into the way of printing them for their own use. I hear that they have sold nearly as many of Blackstone’s Commentaries in America as in England…. This study renders men acute, inquisitive, dexterous, prompt in attack, ready in defense, full of resources…. They [foresee] misgovernment at a distance; and snuff the approach of tyranny in every tainted breeze.

I sighed. “The founding era had truly independent lawyers who owed nothing to government. And many American citizens read and became lawyers, not through official law schools like today, but as checks on government. That’s a whole different system. Citizens were the best checks, if they truly knew the law, because that’s where the lawyers of the era came from.”

My friend was nodding, so I added, “In fact, the same is true of teachers. In the founding era, teachers were hardly ever required to be certified or licensed like they are today. They just studied, read, and started tutoring and teaching. Those who were really good naturally attracted more students—same with lawyers attracting clients.

Freedom and Licensing

Again, today, certified teachers really work for and answer to the state—the entity that certifies them – and in most cases, pays their salaries. Independent teachers who just read and start teaching are more suited to be good checks on government, not its outreach program.

Again, today, certified teachers really work for and answer to the state—the entity that certifies them – and in most cases, pays their salaries. Independent teachers who just read and start teaching are more suited to be good checks on government, not its outreach program.

“The same can be true of any government licensing, such as psychiatric experts. Those who are licensed go to court and give their expert opinions, but people usually don’t take note that these experts can only make a living if they stay licensed. They must comply with state needs, trends and whims. They aren’t independent experts, they are naturally prone to support the government—at least more than they need to be real checks on it. If they don’t, they risk their licensure.

“Of course, if you ask many attorneys, certified teachers, psychiatric experts or others in this position, they’ll often assure you that this isn’t the case. But how can it not be? In any other setting this would be a clear conflict of interest. They’re dependent on the government, given their standing by government, and trained according to government-approved curriculum; this potentially weighs in every situation.

“They may feel that this isn’t full government control, because they can work within the system to fight for various views, and this is true. But it still amounts to a de facto conflict of interest, and it certainly doesn’t promote checks on government abuse the way a non-licensed system used to do.

“So to say that the American Founders had a lot of lawyers is to say that there were a lot of regular people checking the government, while to say that we have a lot of lawyers today is to say we have lots of professionals at least somewhat beholden to the government. The same applies to certified teachers and any others licensed by government.

Following the Old Route

“If society wants lots of licensing, then that’s what we’ll get. But let’s not believe that it creates checks on government abuse. If anything, it does the opposite. When Tocqueville said in Democracy in America that as the lawyers go, so goes America, it was too true! When lawyers were a clear, independent, unregulated check on government, the government was much smaller and more frequently checked. Today, when lawyers and credentialed teachers and many others are beholden to government for their continued licensing, there are fewer checks. Still some, but fewer.

“Of course, some of the lawyers, teachers and others still follow the old route—they are licensed, yes, but they read deeply, think about freedom and are a credit to their professions in the way they stand up for what is right. But the system is still very different, and anyone who cares about freedom should clearly understand the differences.”

“This all makes me want to be a lawyer,” my friend said. “To get licensed and use my law school education to really fight even more for freedom.”

“Bravo,” I replied. “I know a number of lawyers and teachers and others who do the same. I think they are courageous and vital freedom fighters. I also believe that we need a lot of similar leaders in the non-licensed areas, like entrepreneurship, the arts, private school teaching, and so on. If everyone does his or her best in his/her chosen life purpose, that’s where we’ll get the best results as a society.

A Little Bit of Lawyer

“But,” I paused, “this assumes that nobody’s best life purpose is to work daily to reduce freedom. That would be a tragedy, and I don’t believe this is where anyone should dedicate his or her life. Sadly, sometimes people don’t realize this is what they’re doing. We should all take stock of how our daily work is impacting freedom—no matter our profession, career field, job, or work.”

“If we’re hurting freedom, even just because that’s what our career tends to do, we have to change something,” he concluded. Then he paused, pondered, and added, “To sum up, I guess the founders were all a little bit lawyer, a little bit entrepreneur, and a little bit leader.”

“They even had a word for this,” I agreed. “Several words, in fact. Citizen. Voter. Elector. Constituent. American. All of these used to mean you were a little bit lawyer, a little bit entrepreneur, a little bit leader. You’re right.”

He smiled as he nodded. Then he said slowly, “That’s what we need today.”

(Learn about the 3 major ways to deal with these trends in FreedomShift, by Oliver DeMille)

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Oliver DeMille is the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling co-author of LeaderShift: A Call for Americans to Finally Stand Up and Lead, the co-founder of the Center for Social Leadership, and a co-creator of TJEd.

Among many other works, he is the author of A Thomas Jefferson Education: Teaching a Generation of Leaders for the 21st Century, The Coming Aristocracy, and FreedomShift: 3 Choices to Reclaim America’s Destiny.

Oliver is dedicated to promoting freedom through leadership education. He and his wife Rachel are raising their eight children in Cedar City, Utah

Category : Blog &Citizenship &Community &Current Events &Education &Entrepreneurship &Generations &Government &History &Leadership &Liberty &Mini-Factories &Mission &Politics &Statesmanship