Don’t Worry, Be Happy! by Oliver DeMille

June 8th, 2016 // 12:08 am @ Oliver DeMille

Washington’s “Grin and Bear It” Message About an Economy that’s Still Struggling

The Need/Desire Question

In a 1927 issue of Harvard Business Review Paul Mazur of Lehman Brothers wrote the following prescription for the nation: “We must shift America from a needs to a desires culture.” How? “People must be trained to desire, to want new things, even before the old have been entirely consumed. We must shape a new mentality in America. Man’s desires must overshadow his needs.” (Cited in The Happiness Equation by Neil Pasricha, p. 78.)

In a 1927 issue of Harvard Business Review Paul Mazur of Lehman Brothers wrote the following prescription for the nation: “We must shift America from a needs to a desires culture.” How? “People must be trained to desire, to want new things, even before the old have been entirely consumed. We must shape a new mentality in America. Man’s desires must overshadow his needs.” (Cited in The Happiness Equation by Neil Pasricha, p. 78.)

What a thing to say! And it has happened, just as Mazur recommended. But in the process, something else happened as well. Not only were people convinced to want more and newer things, but government got caught up in the same quest. And people began desiring many more and new things from government as well. This changed our entire culture.

More recently, President Obama has assured the nation that a slow growth economy is the new normal. But is this good news? Or very bad news masked by a smile? Truth: it’s certainly not good news. (See the new report: “The World is Flat: Surviving Slow Growth” in the March/April issue of Foreign Affairs)

But before we address this, let’s take a little quiz. Just for fun.

Messages and Meanings

The following quote is about what nation?

(1) “_____________ will not be able to grow its economy…without…privatizing state-owned companies, [and] loosening regulations…”

Or consider this:

(2) “It may have…an undervalued currency, a debt-to-GDP ratio of 250 percent, and an average annual GDP growth rate over the last decade of less than 1 percent…. [but] Life expectancy is among the highest in the world; crime rates are among the lowest. The…people enjoy excellent health care and education.”

One more:

(3) “Middle-class wages stopped rising more than 30 years ago, but…low interest rates…and easy credit obscured the problem, allowing people to bridge the gap between their stagnant incomes and their spending.” How? By going into massive debt.

What is most interesting to me about all three of these quotes is how applicable they are to the United States today. Just re-read item 1 above. It could be a very realistic (and important) “To Do” list for Washington in 2016. Yet it was written about today’s Russia under Putin. (Foreign Affairs, May/June 2016, p. 20)

Still, Washington does need to heed its message:

- privatize state-owned companies that are a drain on taxpayers and gum up the free market

- loosen regulations that are killing small business and sending investment capital to other nations

Item 2 above could also seem to be about the United States, but in fact it describes today’s Japan: “It may have…an undervalued currency, a debt-to-GDP ratio of 250 percent, and an average annual GDP growth rate over the last decade of less than 1 percent…. [but] Life expectancy is among the highest in the world; crime rates are among the lowest. The…people enjoy excellent health care and education.” (Foreign Affairs, March/April 2016, p. 50)

The intended message here is clear: “If the people have good health care, education, and a stable economy, everything is good. A growth economy isn’t necessary.”

Starts and Stops

In fact, in the United States, “Middle-class wages stopped rising more than 30 years ago, but…low interest rates…and easy credit obscured the problem, allowing people to bridge the gap between their stagnant incomes and their spending.” (Ibid., pp. 50-51)

But how have Americans masked falling wages? The answer is illuminating:

- By going into massive mortgage debt (eventually leading to the housing bubble crash and the Great Recession).

- By using credit cards, car loans, student loans and building up major consumer debt. The average U.S. household has over 97 thousand dollars of debt and growing. (The Motley Fool, January 2015)

- By more than doubling the amount of work they do, with both parents typically now in the full-time workforce, instead of just one breadwinner.

- By working longer hours. The average workweek in the United States is now 46.7 hours, not the 1950s model of 40 hours and a crisp 9-5 workday. (USA Today: Modern Woman, Fall/Winter 2015) Over the course of a month, that’s an extra 29 hours—almost an extra workday every week compared to American workers of the 1950s.

- By depending on increasing amounts of government support, including “free” public school education, “free” health care for those who qualify, and a number of even more direct government programs and assistance.

In all this, according to Gallup, less than 20 percent of U.S. workers love their job. Around 80 percent are in jobs they hate, dislike, or feel less than passionate about. Moreover, most Americans don’t believe that their current job will ever get them ahead financially. They’re just barely paying the bills—if that.

Still, the current message from Washington and labor experts is that things are fine, that the economy has improved under president Obama’s leadership, and that we should be grateful. Most people won’t see financial increases anytime soon, “but don’t sweat it.” Like people in Japan, we are assured that we should just be happy for general stability and get used to a stagnant economy.

Fewer jobs, more college-grads who are unemployed or (underemployed) and living with their parents, more three-generation households, falling home values, rising costs of food and necessities—these are the new normal. “And it’s okay,” Washington assures us. “If things get really bad, there are more government programs than ever to help you make ends meet.”

Don’t worry, be happy.

Regulations or Solutions

“Don’t desire so much anymore,” we’re told. “Make do with less. Except when it comes to big government. We’ll give you more of that!”

But how does this message from today’s Washington jive with the reality? Truth: “An economy that grows at one percent doubles its average income approximately every 70 years, whereas an economy that grows at three percent doubles its average income about every 23 years—which, over time, makes a big difference in people’s lives.” (Foreign Affairs, March/April 2016, p. 42)

Factor inflation into these numbers—on the basics like food, housing, education, and transportation—and one percent growth means the average household falls further behind each and every month. At three to four percent growth, in contrast, like the overall average from 1945-2005 in the United States, families can improve their standard of living over time—and even help their kids do better than themselves.

Right now this level of growth is found mostly in Asia, certainly not in North America or Europe. Thus the increasing American realization that our children and grandchildren are likely to be worse off than we are, while their Chinese counterparts will probably experience upgraded lifestyles and standards of living in the decades ahead.

But this isn’t a static reality. It is based on the current policies and agendas of Washington. These can be changed. For starters, just adopt the suggestions Westerners often give to Russia, as outlined above:

- reduce/remove numerous government regulations that are killing small businesses and driving investment capital and high-growth corporations—and jobs—to other nations

- stop federal overspending in so many government agencies by simply cutting their budgets—significantly—to spark increased investment and business growth

Just these two changes would significantly reboot the U.S. economy.

Americans can become a more frugal and a resilient people once again, no doubt. But they would rather be a more innovative and entrepreneurial people—and they have proven that they are incredibly good at it—if government will just cut away the red tape and let free enterprise thrive again.

(Read a lot more on this topic in Oliver’s latest book, Freedom Matters, available at The Leadership Education Store)

Category : Blog &Business &Citizenship &Community &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Entrepreneurship &Featured &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Mini-Factories &Mission &Politics &Producers &Prosperity &Technology

What Should the U.S. Do About ISIS?

November 17th, 2015 // 9:53 am @ Oliver DeMille

After Paris

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in Paris, here’s what we know:

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in Paris, here’s what we know:

- ISIS is cheering the Paris massacres, and vowing that this is only the beginning. They promise that more such attacks on Europe and the United States are ahead.

- One of the terrorist attackers in Paris had a passport on him that showed he came into Europe with the Syrian refugees on small boat through Greece. (It may or may not have actually been his, but whoever put it there must have been sending a message.)

- The terrorists were highly trained, well equipped, and functioned in a way that requires additional support beyond the known attackers.

- ISIS isn’t content to focus on gaining territory in Syria and Iraq. It is a key part of their strategy to take the war to Europe and the U.S. This has been true for a long time, but it is finally hitting home to most Americans.

- Another part of ISIS strategy is to create a Western backlash against Muslims in Europe and the U.S. ISIS wants to create a situation where all Muslims are pushed to choose between the West and ISIS—with no middle ground.

- According to numerous reports on the news, ISIS is calling for supporters who live in Europe and the United States to take initiative and make terrorist strikes on people without waiting for top-down orders.

If ISIS is in fact behind the Paris attack, ISIS has killed over 400 people in less than 10 days—including the Russian airliner, the Beirut bombings, and the 6 coordinated attacks in Paris. Even if ISIS isn’t behind some of these events, they all play directly into the ISIS strategy.

The U.S. Response?

But where does the United States stand on ISIS? Just hours before the Paris attack, President Obama announced that ISIS has been “contained.” The timing couldn’t have been worse for such a statement. After Paris, Obama spoke in strong terms of supporting France, but said little about any response to ISIS.

In contrast, just the night before, Donald Trump announced that his plan for ISIS was to bomb the s%&t out of it. News reports the next morning featured experts pointing out why Trump’s extreme words were out of touch and bad for America. By that very evening, after events in Paris, some of the same channels put on experts saying exactly the opposite. Other candidates spoke strongly of the need to stop ISIS.

The Big Debate

In all this, there is a big debate about what the U.S. should actually do about ISIS. After all, ISIS isn’t likely to just go away.

What should we do? Before Paris, the debate was mainly about whether or not to put American boots on the ground in Iraq and Syria. After the Paris attacks, it’s a whole new world.

Here’s how the debate is now developing:

View A: Airstrikes will never beat ISIS. To seriously stop them, we must put a lot of ground troops into Iraq and Syria-enough to really destroy ISIS once and for all. We’ve waited too long, and President Obama hasn’t been truly committed. Now, with Paris, we know that the terrorists are coming after us in our own nations. It’s time to go destroy them, and that means real ground troops and a “win at all costs” strategy. Find our Patton and go win.

View B: Hold on a minute. Slow down and think. Every time we intervene in the Middle East, we make things worse. Just look at how we armed Saddam Hussein to fight against Iran, and then he turned on us. We eventually intervened to stop Saddam, and most of the weaponry from that war is now in the hands of ISIS. And Iran is still a major problem. Also, look at Libya, which is arguably much worse off than before we intervened. Likewise, Afghanistan is another nation that our intervention made worse in some ways. Let’s stay out of the Middle East.

View A: We disagree. The reason Iraq went to pieces is that we moved our troops out. If we had stayed, the region would be stable. Same with Libya—we intervened but didn’t keep troops there to stabilize things. Same with Afghanistan: it’s only getting bad again because we keep reducing troop levels. As for Syria, if Obama had followed through on his “red line” promise and taken out Assad, Syria would be stable and ISIS would be a minor group with little or no power. That’s the reality.

View B: Really? You actually wish the U.S. had lots of ground troops right now in Iraq, Syria, Libya, Yemen, Afghanistan, and probably Iran? You think that the Middle East can only be stable if the U.S. intervenes in all these nations—and any others where terrorists gather to train and plan—and kills the bad guys, then posts troops in those nations for decades to keep the peace? This is your strategy? U.S. troops in half a dozen nations for the next six decades, like we are in Korea? And the same in any other Middle East nation that has problems? Really? That’s a horrible plan.

View A: ISIS is a new and more modern kind of terrorist group, and its strategy is to take the war to France, Britain, Germany, the United States, etc. It plans to ramp up Paris-like terrorist attacks far and wide in Western Europe and North America. We are at war with these people! Whether we like it or not, they are waging war on us, and this will not only continue but actually escalate as long as we don’t entirely destroy them in their home base—Syria, and even Iraq. What choice do we have? If we don’t destroy them, they’ll keep waging terrorist attacks in Europe and the U.S. They’ll kill hundreds, then thousands. Then they’ll keep killing our people until we absolutely destroy them in their home base. And air strikes won’t do it. Ground troops are essential.

View B: Actually, after four years with ground troops in Iraq and Afghanistan, we still haven’t solved the problem of terrorists coming from those places and attacking Western nations. Ground troops don’t seem to be a real solution. We need something better.

View A: Like what? Ground troops is what works.

View B: But it hasn’t worked. Seriously.

View C: Can I join this debate? I have something to interject here. What about literally bombing them back into the stone age? Bomb their oil. Bomb their buildings, where they might be on computers running their huge financial resources or posting their online recruiting videos. Bomb all their buildings. Flatten them. Leave nothing but dust. We know what areas ISIS controls. Let’s flatten them. Period. It’s us or them. Let’s win this war before it gets much, much worse. Let’s don’t be like Chamberlain appeasing Hitler, hoping ISIS will start being nice. Bomb them until they’re all destroyed.

Views A and B: That’s so barbaric. That’s not the kind of country we are. Think of all the women and children we’ll kill or maim.

View C: The women and children are either slaves of ISIS or supporters of ISIS. For the ones who are slaves, our actions in ending the slavery would be merciful. Just look at the way ISIS treats such people—repeated rapes and maiming and torture and slavery. It’s unspeakable brutality. THAT’S the barbarism. Bombing will create chaos and free a bunch of them, and the ones who are casualties will at least be released from the ongoing torture. On the other hand, those who aren’t slaves are nearly all supporting ISIS. Cut off their support. Destroy them. It’s us or them, and they’re getting stronger. If we let them keep spreading, they’ll eventually gain an air force, missiles that can reach Europe and America, and probably even nukes—given how much money they’ll have. Stop them now.

View A: We can do this humanely, if we get serious about this war and put enough ground troops into Iraq and Syria, and leave them there long enough to really turn things around.

View B: But that might mean a thirty-year war, or more. We’ve already been in Iraq and Afghanistan for fifteen, and we haven’t made much progress. Let’s rethink this. What if we put all our resources into protecting the United States? Let’s protect our borders and protect our cities and states. Let’s focus on our national defense, not on the security of the Middle East.

View A: That sounds good, and we should certainly do that too, but it won’t work if that’s all we do. Just look at the nation of Israel. It is so much smaller than the U.S., with only a few cities and populated areas to protect—like the U.S. trying to protect New Jersey, or to make the point, even New York. Yet in Israel, with armed soldiers on every corner in times of terror threats, and with a huge portion of the adults trained in the military and prepared with weapons to fight, hundreds of terrorist attacks still occur. The U.S. cannot stop a committed ISIS (and other groups like it, of which there are many) that finds ways to recruit homegrown American terrorists online. Nor can Europe do it effectively.

Moreover, if we give ISIS a free rein in the Middle East, by just pulling out all U.S. involvement, it will drastically increase its funding, and its online influence around the world. The number of terrorist attacks in Europe and the U.S. will significantly increase. In fact, if the U.S. pulls out of the Middle East, ISIS will take over more oil, territory, and gain intercontinental missiles and naval and air power.

Make no mistake. ISIS intends to weaken and eventually take over the United States. That’s what the Caliphate is all about—taking over the whole world, starting with anyone who stands in their way. That’s their plan, as many experts on ISIS have been telling us for months.

If the U.S. pulls out of the Middle East, ISIS will grow, strengthen, gain more funding, and eventually attack us with missiles, warships and nukes. We must stop them now. Not barbarically by wiping them out with bombs, like View C wants, but humanely, with ground troops.

Specifically, put enough U.S. and allied troops into Iraq to push all ISIS fighters back into Syria. Then Assad and Putin and Western air strikes can get rid of ISIS. But it starts with ground troops.

View C: No. Let’s not send another generation of our young men and women into a Middle Eastern war zone. Bomb ISIS into oblivion. ISIS doesn’t even have an air force. At least not yet. Let’s do this now, before they expand and gain an air force, missiles, even nukes. Bomb them into the dust. Right away. France will help. Britain will help. Russia might even help. We might even get Saudi Arabia and other moderate Arabic nations to help. Flatten ISIS. Now. It will save more lives and ultimately be more humane—with fewer dead and injured—than any other strategy.

View B: Wait. Think this through. There’s got to be a better way.

Conclusion

This is basically where the discussion in Washington stands right now. What do you think? Ideas?

Do you have any great alternatives to these three main viewpoints? If so, share them.

This is worth thinking about deeply.

Category : Blog &Culture &Current Events &Featured &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History &Information Age &Liberty &Mission &Politics

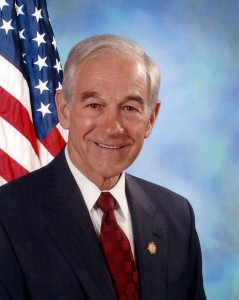

Ron Paul Is the Winner in 2015 by Oliver DeMille

September 18th, 2015 // 7:14 am @ Oliver DeMille

Why the Republican Establishment Is Surprised

(and a bit clueless)

by Oliver DeMille

Shock and Awe

The current presidential election has left most of the Establishment speechless. They are shocked by the rise of Bernie Sanders, shocked by the success of Donald Trump in the polls, and shocked by the popularity of Ben Carson. “Shocked” may actually be too weak a word. Apoplectic, maybe?

The current presidential election has left most of the Establishment speechless. They are shocked by the rise of Bernie Sanders, shocked by the success of Donald Trump in the polls, and shocked by the popularity of Ben Carson. “Shocked” may actually be too weak a word. Apoplectic, maybe?

The Establishment is also surprised by the struggles of Hillary Clinton, Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, and Scott Walker—all of whom were widely predicted to dominate this election cycle.

“Why is this happening?” is a popular question on many political news programs right now. Along with: “Will it continue?” “What will happen next?” and “Why are the voters so angry?”

Conservatism 1.0

The answer is fascinating. To get there, let’s start with the roots of the modern conservative movement. Initiated largely by William F. Buckley, Jr. and his colleagues in the 1950s and 1960s,[i] Conservatism 1.0 struggled, persisted, gained support slowly, and then rose to victory with the election and presidency of Ronald Reagan.

The Party of Reagan was based firmly on the view that “liberalism is bad.” In this environment, Reagan’s GOP found itself directly opposed to the Democratic Party of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his progressive successors.

The ensuing debate pitted conservatism against liberalism in a few direct, simple ways: limited government versus big government, Constitutional originalism versus judicial activism, American exceptionalism versus European style internationalism, and individualism versus collectivism.

Republicans saw conservatism as good precisely because it espoused limited government, strict adherence to the Constitution, American leadership in the world, and individual freedoms. They saw liberalism as bad because it promoted big government, an activist Court, American subordination to international organizations, and widespread collectivism through higher taxes and increased government programs in all facets of life.

This was the battle of Postwar America. And conservatives saw themselves as the Keepers of Freedom and Family Values in this monumental conflict—warriors for the American Dream and the American way of life.

After the financial downgrade of the Soviet Union during the Reagan years and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the battle lines were slowly redrawn. New superpowers emerged on the world stage, and existing alliances began to unravel. Naturally, during the 1990s the old battles were replaced with new ones, and in the 2000s world and national allegiances were weakened, redirected, and reconceived.

But the hearts of many 20th Century conservatives (and liberals, for that matter), raised and steeped in the old battles, didn’t change.

Conservatism 2.0

A new cultural movement sprouted in the different soil after 1989. In technology, this shift was exemplified by Steve Jobs, and eventually Elon Musk. In business, the iconic figureheads were Bill Gates and Warren Buffett. And on the political front, the pioneers of a new model were Ross Perot and Ralph Nader, and later Bernie Sanders and Ron Paul.

A new cultural movement sprouted in the different soil after 1989. In technology, this shift was exemplified by Steve Jobs, and eventually Elon Musk. In business, the iconic figureheads were Bill Gates and Warren Buffett. And on the political front, the pioneers of a new model were Ross Perot and Ralph Nader, and later Bernie Sanders and Ron Paul.

Congressman Paul’s contribution to the new brand of conservatism that arose is hard to overstate. For example:

- It replaced Reagan’s 11th Commandment (“Thou shalt not criticize other Republicans”) with a focus on principles of freedom rather than institutional political parties.

- It walked a fine (and frequently uneasy) line between party loyalty and going independent, finally resting on the idea that independence is more important than party—but sometimes it’s possible to get both.

- It called into question widespread U.S. military interventionism.

- It reemphasized the Constitution as a central, literal theme, rather than a mere national symbol.

- It put actual free enterprise above the rhetoric of free enterprise (rhetoric that most Republican presidents had ironically combined with bigger government).

- It appealed strongly to populism—“this is the people’s government, not vice versa.”

- It switched the viewpoint of conservatism from “liberalism is bad” to “government by elite power brokers and their bureaucratic agents is bad.”

Paul himself wasn’t able to convert this revolution into a White House victory, but the revolution occurred nonetheless. And the 7th point of this revolution is perhaps the most important. It animated the Tea Parties, the elections of 2010 and 2014, and it is still growing today.

It also explains the shock of the current Republican Establishment with the ousting of Eric Cantor, the support for Donald Trump, Ben Carson, and Carly Fiorina, and the popularity of Ted Cruz in comparison to Jeb Bush or Scott Walker.

Mitch McConnell, John Boehner, John McCain, Mitt Romney, Jeb Bush, and most of the Republican Establishment are operating as if the GOP is still Reagan’s party. But this is debatable. A large segment of the party is now more aligned with Conservatism 2.0.

Thus the passionate battle now underway for the future of the GOP. And with each passing election cycle, the popularity of Conservatism 2.0 is increasing.

What 2.0 Conservatives Want

To these new conservatives, the idea that “liberals are bad” is SO forty years ago. The real issue now is that “government by elites” is bad.[ii] “The elite class is bad. It is corrupt, and it’s hurting us all. It is hurting America.” In fact: “Corruption is bad. And elites are corrupt.” This viewpoint is growing.

And to members of the new conservatism, Republican elites are just as bad as liberal elites. Many consider them even worse, like modern wolves in sheep’s clothing, claiming conservatism, and gaining support for their candidates and policies by invoking conservatism, while refusing to passionately or effectively fight for it.

It is important to clarify that the Ron Paul revolution didn’t win all 7 of its main themes. The new 2.0 conservatives never warmed up to items 3 and 4, for instance:

3-less U.S. military interventionism in the world

4-more emphasis on the literal words of the Constitution

But, on the other hand, they bought the following principles hook, line and sinker:

1-focus on principles of freedom rather than institutional parties

6-populism: forget “electability” and support the candidate we think will really bring about the changes we want

7-government by elites is corrupt and bad

This tectonic shift put Carson, Trump, Fiorina and Cruz at center stage.

A Question

It remains to be seen if a 2.0 candidate can become the nominee anytime soon. And even more significant is the question of whether a 2.0 president will actually apply item 5 from the list:

5-actual free enterprise is the goal, not just the rhetoric of free enterprise

Such an approach would lead to balanced budgets, reversal of the U.S. national debt, and a high-growth economy spurred by a massive rollback of anti-small business regulation. Right now many 2.0 voters are split. They’re asking themselves if Trump or Fiorina would actually lead a serious downsizing of government—or instead just expand government like past 1.0 conservative presidents.

As for Carson and Cruz, they seem clearly committed to this approach, but 2.0 conservatives wonder if they have the capacity or authentic will to actually pull it off.

If the 2.0 crowd ever coalesces around one candidate, he or she is going to be very hard to beat—in the primaries, and even in the general. A motivated 2.0 nation will be very persuasive among independents, women, and young voters. And 2.0 is very strong in the swing states. But 2.0 conservatives won’t “go for it” if they are at all uneasy about the candidate’s direction or ability. They are, in a sense, playing the long game, and won’t blow their one-shot-at-the-big-house political capital on an also-ran.

The Election

A long primary and general election fight is still ahead, and this war between conservatism 1.0 and 2.0 won’t be easily resolved. It has already turned nasty, and it will probably get a lot worse.

But if 1.0 wins, if Jeb or another Establishment candidate is the eventual nominee, this fight will rage on. Conservatism 2.0 is young, passionate, and has the benefit of a large and growing base. It may or may not get its way in 2016, but all indications are that it will eventually win the war.

When it does, expect the president it propels into the White House to alter American history as significantly and lastingly as the 1.0 movement did with Ronald Reagan.

(Read more discussion on these themes in FreedomShift, by Oliver DeMille)

[i] With significant support by additional voices including Leo Strauss, Milton Friedman, Leonard Read, Friedrich Hayek, Russell Kirk, Richard Weaver, Ludwig von Mises, Ayn Rand, and Margaret Thatcher, among others.

[ii] In comparison, Liberalism 2.0, supported early on by Hobson and Mencken and Keynes, among others, and perhaps most embodied in current events by President Obama (and espoused by Bernie Sanders), frequently operates on the idea that “America is bad.” European social democracy is promoted as the alternative, the ideal, and the goal.

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History &Independents &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Politics &Statesmanship

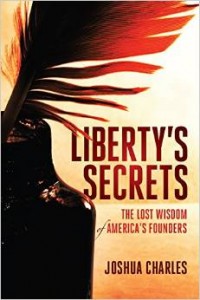

A New Great Book in the Battle for Freedom! Review by Oliver DeMille

August 19th, 2015 // 2:36 pm @ Oliver DeMille

Steps to Freedom

I read another great book today, and it rekindled my sense of hope for the future. If you care about freedom, you’ve got to read it! This new classic is Liberty’s Secrets by Joshua Charles, and it is…

I read another great book today, and it rekindled my sense of hope for the future. If you care about freedom, you’ve got to read it! This new classic is Liberty’s Secrets by Joshua Charles, and it is…

But I’m getting ahead of myself. There’s a story here, an important one. And I need to tell it in order to do justice to this book. In a world of brief sound bites and too frequently shallow media and educational conversations, a great book is easily overlooked. Such greats all too often go unnoticed because we live in an era of constant—aggressive—distraction. So to introduce a genuinely great book, we need to get this right. Here goes…

I. The Great Books

I was a young boy when first it happened, old enough to ride my bicycle to the library on hot summer afternoons and find interesting books to read, but young enough that high school sports and summer trainings weren’t yet part of my daily routine. One day under the memorable breeze of the town library’s large swamp cooler I came across a long shelf of books that boldly called themselves “The Great Books”. I stopped and stared. I re-read the title, then pondered.

“These can’t be the only great books,” I reasoned to myself. “There must be others.” Intrigued, I pulled out a volume and perused the title page, then skimmed through several chapters at the beginning of the book. I was impressed by the small print, the columns and footnotes, and the sheer quantity of big, unfamiliar words. They were downright intimidating.

I marveled a bit, rubbing my fingers along the cloth-covered bindings. I knew I would read these books some day. I just knew it.

I remember nothing specific about which volumes I investigated that day, but I skimmed many of them, reading a sentence here and another there. The afternoon passed, and I eventually returned the last volume I’d removed to its place on the shelf and went to the front counter to check out the L’Amour novel I’d selected for the week’s reading.

We lived in the desert, and it was a very hot summer, so during the exertions of my bike ride home I forget about the “Great Books”. But each time I returned to the library, I noticed them again. It seemed like none of them were ever checked out, and I could well believe it. They were truly daunting, with their gold foil lettering, fancy author names, and massive domination of shelf space.

II. Fast Forward

Today I just finished reading a truly great book on freedom, and I smiled widely as I completed the last few lines and closed the book. I removed the dust jacket and ran my fingers over the sleek black hardcover with the red foil print. “I was right, that day,” I thought to myself.

Then I realized I had been right on both counts. I would, in fact, come to read the whole set someday. I couldn’t have known at the time that I would re-read The Great Books many times, teach them extensively in multiple university, high school, and graduate level courses, and spend many hours discussing their content with colleagues, business executives, students, professionals, family members, and friends. The Great Books volumes have become dear friends over the years, and I have returned to them often for heated debates with their authors or to rehash unfinished questions in the “Great Conversation”.

But I was right about the other thing as well: there are great books beyond those in Britannica’s 54 volume set. And when I encounter an additional great book, I always feel a sense of excitement. Great books are great because they are important. That’s the major criterion. They have to be truly significant, to add meaning to our world—to innovate something that wasn’t there before the book brought it to life.

III. What Makes “Great”?

Over the decades I’ve experienced several great books beyond those from the “official list,” and they always leave an impression. Like The Closing of the American Mind by Allan Bloom, The Third Wave by Alvin Toffler, or The Five Thousand Year Leap by W. Cleon Skousen. Such books, like those by Bastiat or Austen, simply must be added to list. Along with Solzhenitsyn’s works.

In recent years I’ve come across several additional great books, like Andy Andrew’s The Final Summit, Chris Brady’s Rascal, Stephen Palmer’s Uncommon Sense, Orrin Woodward’s Resolved, Judith Glaser’s Conversational Intelligence, or Henry Kissinger’s On China. I also studied an old great book I hadn’t ever read before, The Early History of Rome, by Livy, and found greatness in its pages as well. When you read a book that is truly great, it’s a moving experience.

Such books come along rarely, so when they do it is important to pay attention. But what makes a book genuinely great? After all, greatness is a very high standard. It can’t just be good. As Jim Collins reminded us, good is too often the enemy of great.

Nor can it simply be well written. It can’t merely be accurate, detailed, beautiful, or interesting. More is necessary. It can be one, a few, or all of these things, but to be truly great, it must be also be transformational. It must change you, as you read.

IV. A New Great Book!

When I started reading Joshua Charles’ book a few days ago, I didn’t know I was in for such a treat. I had already enjoyed his earlier bestselling work, so I was ready to learn. I got my pen and highlighter out, and opened the cover. But as I read I realized that this book is truly very important. Needed. And profound.

Then, as I kept reading, I noticed that I was feeling something. A change. A different perspective. A re-direction. I was experiencing…the feelings that always accompany greatness.

Charles notes in several places that as a member of the Millennial generation he felt compelled to share this book with the world. Why? Because, in his words: “I wrote this book for one reason, and one reason only: to reintroduce my fellow countrymen to the Founders of our country and the vision of free society they articulated, defended, and constructed, in their own words.”

As a member of Generation X, I was thrilled to see a Millennial take this so seriously—and accomplish it so effectively. Even more importantly, as I read I noticed something very important, subtle but profound. Charles doesn’t make the mistake of so many modern authors who write to the experts and professionals in a field. His scholarship is excellent, and he goes a step further. He has a more important audience than mere political or media professionals. He writes to the people, the citizens, the voters, the butchers and bakers and candlestick makers—the hard-working people who make this nation go, including the artists, scientists, teachers, executives and leaders.

In so doing, he is a natural Jeffersonian, speaking the important principles of freedom, culture, economics, and leadership to a nation of people—not merely to politicos or aristos, but to everyman. To underscore this (and I doubt it was a conscious decision on his part, but rather his core viewpoint), his word choice refers not to “the American voter” but rather to “we the people.” He considers himself not merely the expert, but one of us, one of the people.

I could have hugged him for this, had he been here in person. We have far too few freedom writers today who see themselves truly as part of the citizenry. When they do come along, albeit rarely, I feel a sense of kinship and I know that their hearts are in the right place. Jefferson would be proud. For example, Charles wrote:

“We no longer know where we came from, the grand story we fit into, and the great men and women who inspired the noble vision which birthed the United States of America, the first nation in history to be founded upon the reasoned consent of a people intent on governing themselves….

“Additionally, few of us are well-read enough (a problem our educational system seems blithely unconcerned with) to discuss the lessons of the human experience (often simply called ‘history’)…”

Freedom, the classics, voracious reading, leadership, and the future—all rolled into one. “This is my kind of author,” I realized, once again. “These are the themes I emphasize when I write.” So did Jefferson. And Skousen, and Woodward. No wonder I love this book.

The Current Path

More than profound, Charles’ book is also wise. Belying his Millennial generation youth, he speaks like an orator or sage from Plutarch when he warns:

“Liberty is difficult work. It is fraught with risks, with dangers, with tempests and storms. It is a boisterous endeavor, an effort for the brave and the enterprising…”

These latter words have stayed with me since I read them several days ago. I keep remembering them. Boisterous. Brave. Enterprising.

These are the traits of a free people. In classical Greece, among the ancient Israelites, in the Swiss vales, the Saracen camps, the Anglo-Saxon villages, and the candlelight reading benches of the American founders—wherever freedom flourished. Yet today we train up a nation of youth to be the opposite. To fit in (not boisterous). To avoid risk (not brave). To focus on job security above all else (not enterprising).

If this trajectory continues, our freedoms will continue to decline.

Where and When

Speaking of freedom, Charles calls us to immediate action with his characteristic humility, depth, and conviction: “We either pass it [liberty] on to our posterity as it was passed down to us, or it dies here and now.”

Here and now? Really?

Is it that immediate? Is it truly this urgent? Is it really up to us?

The answer is clear: Yes.

Yet, it is.

“He gets it.” I smile and take a deep breath. Then I whisper to myself: “Another great book!”

I hold the book sideways and look at the many pages where I have turned down the corners. Dozens of them. Just for fun, I open one of them and read:

“…we have every reason to be doubtful of, skeptical about, and disdainful toward the notion that Caesar [government] can solve all our problems.”

I nod. When freedom is under attack, leaders rise up from among the people. This book is part of that battle.

“The Great Books indeed.” I grin as I say the words.

I turn to another page with a dog-eared corner and read Charles’ words:

“‘Society is endangered not by the great corruption of the few, but by the laxity of all,’ Tocqueville had noted, and on this he was in complete agreement with the Founders.”

And now, I note, with at least one Millennial.

I feel a sense of building hope for the future. “The Millennials are beginning to lead,” I say with reverence.

“This is big. And if this book is any indication of what’s to come…

“It’s about time,” I say aloud.

Then, slowly, “Everyone needs to read this book.”

*Liberty’s Secret by Joshua Charles is available on Amazon

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Book Reviews &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Education &Featured &Generations &Government &History &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Politics &Statesmanship

An Obama, Adams, and Jefferson Debate

June 1st, 2015 // 6:15 pm @ Oliver DeMille

(Should Presidents be Treated Like Royalty?)

News and Fans

A strange thing happened recently. President Obama visited my state, just a quick flight and a few meetings. But to watch the state news reports, you would think the most important celebrity in all of history was visiting. The media simply fawned over the president. The news channels broke into all the nightly television programs and gave special reports. Not on some major announcement, but on…wait for it…the President arriving at his hotel.

A strange thing happened recently. President Obama visited my state, just a quick flight and a few meetings. But to watch the state news reports, you would think the most important celebrity in all of history was visiting. The media simply fawned over the president. The news channels broke into all the nightly television programs and gave special reports. Not on some major announcement, but on…wait for it…the President arriving at his hotel.

Reporters were on the scene. Anchors cut back and forth between the reporters and expert guests opining on how long the President’s day flight been and how much longer before he would arrive at the hotel. This went on and on. No news. No policies. No proposals. No events. No actual happenings.

Just a president and his entourage arriving in a plane, being driven to the hotel, and staying overnight. The reporters and other news professionals—on multiple channels—were positively giddy.

I shook my head in amazement. The American founders would have been…well, upset. At least Jefferson would. Adams? That’s a different story altogether. In fact, it got me thinking.

John Adams, the second president of the United States, made a serious mistake during his term in office. He had served for a long time as ambassador to the English crown, and he picked up some bad habits in London. He witnessed the way members of Parliament treated the top ministers in the British Cabinet, and how the ministers themselves fawned over the King.

He had, likewise, watched how the regular people in England bowed and scraped to the aristocracy. Almost everyone in Britain saw every other person as either a superior, an inferior, or, occasionally, an equal. This class system dominated the culture.

And, as an ambassador of the American colonies, Adams had been pretty low on the pecking order in London. He had seen how this aristocratic structure gave increased clout to the King, to Cabinet members, and to the aristocrats. So when he became president, he wanted the U.S. Presidency to have this same sense of authority, power, and awe.

In fairness, reading between the lines, I think president Adams’ heart was in the right place: He thought this would help the new nation gain credibility in the sight of other nations. He wanted the president to be treated like royalty.

But Adams forgot something very important.

Aristos and Servants

Americans weren’t raised in such a class system. They found such bowing-and-scraping to the aristos both offensive and deeply disturbing. For them, this was one of the medieval vestiges of the old world that America (and Americans) had gratefully left behind. The principle behind this was simple: if we treat leaders like aristos and kings, they’ll start acting like aristos and kings, and our freedoms will be in grave danger.

Moreover, Americans felt that such “prostration before their betters” was especially inappropriate where government officials were concerned. “Government leaders work for us,” was the typical American view. And if the citizens start acting like their leaders are aristocrats and royalty, they’ll stop thinking and acting like fiercely independent free citizens.

Moreover, Americans felt that such “prostration before their betters” was especially inappropriate where government officials were concerned. “Government leaders work for us,” was the typical American view. And if the citizens start acting like their leaders are aristocrats and royalty, they’ll stop thinking and acting like fiercely independent free citizens.

But still Adams wanted the people to treat the president like royalty. Jefferson was appalled at Adams’ words and behavior in this regard, and his criticisms of President Adams’ on this matter fueled a rift between these two men that lasted almost two decades. At times, the biting rivalry and harsh words bordered on hatred—if not of each other, certainly of the other’s behavior.

Jefferson believed in a democratic culture, where each person would be judged by his choices and character—not by class background. Even more importantly, he believed that, in fact, government officials do work for the people—and the higher the office, the more they are servants of the people.

As president himself, Jefferson went out of his way to avoid and reject any “airs” or special perks of office. He saw himself as simply a man, one of the citizens, who had the responsibility to serve all the other citizens. He wasn’t superior to them—he was the least of them, their servant, their humble servant.

After 8 years as president, Jefferson had established this as the way each president should be viewed: a regular citizen, serving as president while elected, but not treated as inherently royal, superior, or in any way better than anyone else. No perks, no special treatment. Yes, security for the Commander in Chief obviously needed to be different than for the average person. But other than that, no aristocratic fawning was appropriate.

Madison followed the same model, and after him Monroe. So did John Quincy Adams and other presidents through the eras of Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt, and FDR. Truman angrily rejected any attempts to put him on an aristocratic pedestal.

Eisenhower rebuffed aristocratic perks both as a general and later as president, and Kennedy did the same in many ways—leaving his expensive upper-class clothes at home and dressing more like the people he worked with each day while in Washington. Reagan openly pushed against any aristocratic airs; as a movie star he was accustomed to celebrity, but clearly avoided it as president. He wanted to be a man of the people, a servant.

Generational Visions

And even while Adams tried to promote a higher level of fawning over the president, at least the media of his era had the good sense to criticize him for it. To take him to task. To note that such is not the American way.

But something changed, somewhere along the way. Was it because Kennedy was considered American “royalty” even before the presidency, or because Reagan was already a Hollywood celebrity before he occupied the White House? Or did the change come during the Clinton era, or the Bush years? (Ironic that such fawning of the Chief Executive came after Nixon.)

Or was it the way Hollywood portrayed presidents—with actors like Michael Douglas or Martin Sheen glibly spouting a sense of arrogant power and aristocratic entitlement? Did entertainment capture our national imagination?

When did we start seeing the world as classes of royals, aristos, and “regular” people? When did “celebrity” become an accepted reason for special treatment in America?

Should we respect the offices held by our political leaders? Absolutely. Should we honor those who serve? Absolutely. Too often the level of civic discourse today is coarse and angry. More respect is needed. And, just as importantly, less aristocratic fawning is needed.

I once wrote about experiencing this trend firsthand while hosting a visiting dignitary many years ago. After an evening event, we went to a restaurant. The dignitary and I naturally walked to the back of the line, but one of the other hosts hurried to the front of the line and arranged for a “VIP table.” As we walked past the rest of the line, people vocally grumbled. We heard words like: “Hey, don’t cut in line,” and “You can wait your turn, just like the rest of us.”

When the other host responded by telling the people in line the dignitary’s title and name, the frustration grew louder. “We’re Americans too,” one man said. “We don’t worship titles in this country. Wait your turn.” A number of similar words were exchanged. The dignitary demanded that we go back to the end of the line just like everyone else.

Fast forward over two decades later. A similar scene. I walked with a dignitary to the back of a large restaurant line, and someone in our group arranged for us to go straight to our table. As we passed the line, people asked, “Who’s cutting in line?”

But these voices weren’t angry. They were just curious. “It’s a celebrity,” someone said. “Oh, okay,” was the general consensus. “Of course. Let him ahead, then.” Apart from trying to see if they recognized the person, everyone in the line seemed totally content to let a celebrity pass.

The earlier line had been made up mostly of people from the Greatest Generation and the Boomers, while the second line consisted mainly of Gen X and Millennials. The U.S. clearly changed during the two decades between these experiences. But is the change a good one?

It’s an important question: Can we maintain a democratically free society when the broad culture sees people as “superiors,” and “inferiors”? When we as Americans have come to see celebrities as naturally deserving special perks, and government officials as people to be submitted to? Won’t that change how we vote?

Indeed, it already has.

Focus and Fawning

Would John Adams like the way Americans now treat their presidents and other celebrities? What would the British aristos of the American Founding era think of Americans today? Are we just as “domesticated” as the London populace of their time? We don’t exactly “bow” yet, but have we become a nation that “bows and scrapes” before people we see as “our betters?”

And if this applies to “power celebrities,” meaning government leaders, what does that say about the American people as wise stewards and overseers of freedom? Politeness is good, no doubt. But which is classier:

- A people who move aside for aristos, craning their necks to catch a glimpse of celebrity and snap a photo on their phones, or,

- A people who think everyone is an important leader because we are all citizens of a great, free nation?

Whatever Adams would think of the way many Americans now turn giddy in the presence of political leaders, Jefferson, Washington, Franklin and Madison would not like it. Jefferson would certainly call foul. This is not the way to maintain a true democratic republic.

Whatever Adams would think of the way many Americans now turn giddy in the presence of political leaders, Jefferson, Washington, Franklin and Madison would not like it. Jefferson would certainly call foul. This is not the way to maintain a true democratic republic.

Treat everyone like aristos, or no one. Period. That’s the only way to be equal and fair.

Don’t treat some like aristos and others like commoners. Because if we do, freedom will quickly decline. (It will decline more for the commoners than the aristos, by the way.) Even Adams hated such obsequiousness when he witnessed it in Europe.

Clearly, as mentioned, the security of top leaders is very important. So is the security of everyone else, but it is true that top officials and celebrities often face more frequent threats. Also, more respect in our civil discourse is needed. But the servile toadying to political celebrity by many in our current populace and even media is a disturbing trend.

Again, we should certainly be respectful of important office. But sycophancy isn’t the American way—as Adams learned when the “commoners” refused to give him a second term. In fact, they instead entrusted the presidency of their nation to the leading voice of democracy and equal treatment for all citizens: Thomas Jefferson.

We should be so wise. Give us a president who stands what matters—boldly, openly, and effectively—while simultaneously rejecting the perks and “airs” of aristocracy, or worse, an Americanized royalty.

Give us a president who vocally reminds us that he or she is just one of the citizens. And who openly remembers and operates on the principle that we, the people, are the real leaders of the nation. It’s time for the media servility and simultaneously smug superiority of the White House to be replaced with what our nation actually needs—quality, grown up, leadership by someone who truly understands what makes freedom tick. The people.

As for the media, focus more on policy and principles, less on ratings and the “royals who lead us.” And none at all on what hotel somebody stays in. There are people with real needs in this country, and current policies are hurting millions of American citizens. Let’s fix them. Starting with spending our media airtime on what really matters.

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Featured &Generations &Government &History &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Politics &Statesmanship