The Madison-Jefferson Debates: What Isn’t True

August 7th, 2018 // 1:22 pm @ Oliver DeMille

Reality or… Not?

Some things just aren’t true, even if we think they are. Even if we are assured that “everyone” says they’re true; and even if the experts—almost always unnamed—have formed a consensus on the matter. Actually, the more you get know the experts, the more you realize they aren’t in consensus on almost anything.

Some things just aren’t true, even if we think they are. Even if we are assured that “everyone” says they’re true; and even if the experts—almost always unnamed—have formed a consensus on the matter. Actually, the more you get know the experts, the more you realize they aren’t in consensus on almost anything.

Now, let’s be clear. A lot of what we’re told is true. But not everything. And that’s why sometimes it’s important to take a step back and really dig into things. Research. Find out. There are whole websites dedicated to setting the record straight about urban myths, generally accepted “truths”, quotes that are attributed to someone who never said those words, etc. We give “Pinocchios” to politicians who fib, and “Fact Checker” is a growing career field in the Information Age. (Is it really? Or does it just seem like it? Ask the question on Google and you can spend hours studying the various listings. Or ask the same question on social media and wade through hundreds, or even thousands, of opinions.)

Falling for Everything

Here are few items that most people consider truth. Unassailable. Set in stone. Incontrovertible.

- Lie Detector Tests

- DNA Evidence

- Election Polls

- Carbon Dating

Which are sure? Which are certain? Not all. Do you know which of these are fully accepted by the experts in the field—no exceptions? Answer: none. All of the above are rejected by at least some experts, even where a majority of experts agree. Have you studied the arguments, evidence, tests and conclusions on each? Or any? Note that even where the science is firm, like with DNA evidence for example, the way experts present such science is at times incomplete or misleading. Or, another example, even if the statistics used in a pre-election survey are accurate, the wording of a specific survey question can skew the entire result; and what if survey respondents are afraid or ashamed to tell the truth, like in the 2016 U.S. presidential election when many voters didn’t want people to know they planned to vote for Donald Trump? In such cases, the math and the science can be technically correct, but the way experts use them turn out “wrong”, because all the variables aren’t controlled.

In short, on many things we simply know less than we need to. And yet most people are comfortable making decisions based on things they know very little about—just taking someone’s word for it. It’s a habit for most people.

But things are not always what they seem. Truth isn’t always what the experts claim. This doesn’t mean that every crackpot theory questioning the experts is correct. But it does suggest that we should be independent thinkers who read the original data or studies where possible and scrutinize things for ourselves. Independent thinking is required to maintain independence. This is obvious, isn’t it? But most people don’t follow this approach.

Time to Think

For our Madison-Jefferson conversation this week, I’m recommending the attached article. It is a great read, and an important one. It demands that we look at things more deeply, and think more wisely. It calls us to research more, question more, dig deeper, and not just accept conclusions at face value. It is one of those articles everyone should read and deeply consider. Agree or disagree, this article will make you think!

Enjoy…

How Social Science Might Be Misunderstanding Conservatives >>

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Business &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Featured &Generations &Government &History &Independents &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Politics &Producers &Prosperity &Science &Statesmanship &Technology

The Jefferson-Madison Debates: The Third Layer

July 17th, 2018 // 7:08 am @ Oliver DeMille

“When technology advances too quickly for education to keep up,

inequality generally rises.”

—Eric Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAffee

“Your true greatness comes when you focus not

on building a career but on finding your quest.”

—Vishen Lakhiani

“Engaged students are 16 times more likely to report being academically motivated than students who are not engaged. Finding ways to engage the 40% of students who are not engaged would have a significant impact on their academic motivation.”

—Quaglia Institute

Foundations

Education is like a map. Or, more precisely, it mirrors the entire field of maps and map-making.

Education is like a map. Or, more precisely, it mirrors the entire field of maps and map-making.

Understanding the massive change now occurring in how we make and learn from maps is in many ways directly applicable to the coming changes in education. And like in education, many people in the older generations (born before 1980, or even 2001), don’t understand that a major revolution is ahead—one so big that what we call a “map” today won’t even qualify as a map in twenty years. (And much of what we call an “education” today won’t even count as education two or three decades from now.)

The pre-modern map (Layer One) emphasized the physical traits of the earth: continents, oceans, seas, rivers, mountain ranges, islands, etc. More advanced pre-modern maps included things like ocean currents, the altitudes of mountain peaks, and the trade routes most effectively used by overland and shipping merchants.

During the modern era, we added governments to our maps (Layer Two): national borders, towns, cities, capital cities, provinces, states, counties, etc. This was part of the great shift from pre-modern to modern. Governments and their jurisdictions became as prominent in world affairs as the natural physical features of the earth. People using maps needed to know what government they’d be dealing with in a given spot as much as where the ocean currents would take them and what mountains or rivers they’d need to traverse.

Further Up and Further In

The current shift from modernism to post-modernism is equally momentous. Our maps now require another set of symbols, colors, and words—to tell us what we need to know about our world. The physical features on the maps (continents, oceans, rivers, mountains, lakes, etc.) are still there, as are the political borders that tell us what government controls each area on the illustration.

But now a third layer of understanding is superimposed on top of the physical and political levels of each map. Most people haven’t even seen such maps yet, so they think of a “map” as something made up of Layer One (mountains, rivers, oceans, etc.) and Layer Two (borders, cities, etc.). They barely fathom what else could be needed.

The post-modern Layer Three is based on what Parag Khanna calls “Connectography.” For example, look at a traditional map of Africa. The Nile is there, and the Cape. The Horn of Africa is obvious, along with the Sahara. There are regions of jungle, and large swaths of savannah. Then there are the many nations and their borders—most of them originally established by European plantation owners. Capital cities are listed in bold letters, the names of nations in larger type.

But where is Layer Three? At its most basic, Layer Three shows highways, airports, and hospitals. In a more detailed Layer Three map, you might find illustrations showing the route of pipelines, Internet cables, or even power lines. These were the simple beginnings of Layer Three maps. A little more advanced Layer Three maps don’t just tell you what road to take, they tell you how long it will take to arrive in current traffic—or redirect you if an accident occurs and is now blocking traffic. They are cast in real-time and they are always changing—truly interactive. Layer Three is a major upgrade.

But more is coming. For example, narrow the map of Africa to Kenya or Ghana. Where are the hotspots of Internet usage? Where are the Internet deserts? What about smartphone usage rates? What food is shipped to a place, and can you get the kind of banana and cereal you want while you are visiting? If you want salmon for dinner, will what you are served be farm raised or wild? – Come from the Atlantic or the Pacific? What nation’s laws governed the fishermen who caught your dinner? Such information tells you a great deal about the probable quality and freshness of what you’ll be eating, and whether or not to even order it.

Put these on the map, and you’ll begin to see how Kenya, Ghana, or any other nation in Africa, or anywhere else in the world, is actually connected. Not understanding such connectivity—or its absence in a certain area—is akin to not knowing what the political lines denoting borders signify on the map. Such ignorance basically renders the user of the map illiterate.

Consider an almost-absurd example, to illustrate:

“Are these lines just very straight rivers?” a total map novice might ask. The laughter that follows is kindly, but surprised. “How can anyone not know about government borders on a map?”

In the future, however, this will apply to much more than national borders.

A Missing Piece

Another Layer Three example is very important: For example, on the map of Kenya, what natural resources are owned by or contractually promised to Chinese companies or the Chinese government? Versus what resources are owned by or contracted to U.S. firms? Or Canadian?, Dutch?, Japanese?, Italian?, British?, French?, German?, Korean?, Indian?, etc. What multi-national companies have their own security forces at work in these places—governing, citing, controlling? Where have they blocked mobile phone and Internet service—and why? If you know the Layer Three map of Africa this way, you’ll understand the world in ways other people simply cannot grasp. As Khanna put it: “China’s relentless pursuit of [natural resource contracts around the world] has elevated…to the status of a global good on par with America’s provision of security.”[i]

In other words, if anything happens militarily in the world, the U.S. is sure to get involved (or at least consider getting involved); and if anything happens concerning natural resources—oil, minerals, food, wood, precious metals and gems, water, etc.—China is sure to jump in. It likely already has contracts signed and sealed. In fact, put alliances and treaty requirements on the map, and something stands out: China owns numerous economic resources around the globe that the U.S. does not. Moreover, as of 2015 the United States was bound by treaty to defend 67 nations in the world; China was only bound to protect 1.[ii]

In short, a lot of global resources and money are slated to flow to China in the decades ahead (it has already begun), while huge assets and cash are scheduled to flow away from the United States. One has an economy that is programmed to head up, the other down. If you don’t consult a Layer Three map, this information is unknown.

Look at the map with the Layer Three approach, however, and the future becomes immediately clear: It belongs to China. The U.S. and Europe[iii] are falling further and further behind. This is obvious on a Layer Three superimposition.

But remove Layer Three and all you have are the continents, oceans, lakes, mountains, political borders, cities and towns. Nothing about Levels One or Two tell you that China is on the rise—with contracts across the globe, and a growth rate in ownership of natural resources and supply chains for these resources that all but assure them monopoly status in the decades ahead. And this example, China, is only one of the many hugely important things missing from Layer Two maps—which are the only ones most of us ever engage.

To reiterate: the pre-modern and modern maps fail us. They don’t even tell us what we need maps to communicate (rather than merely travel) in order to help us make the best local decisions. As a result, the old maps are almost worthless. They are historical relics, but not the most effective tools of decision-making or strategy.

For that, we need Level Three maps superimposed on the older models. As Joshua Cooper Ramo put it: “Ball up your right hand into a fist. Take your left hand and open the fingers wide. Hold the hands a few inches apart. You can think of your left hand as the vibrating, living network of connection and your balled-up fist as concentrated power. Right hand, Google Maps; left hand, millions of Android phones. This is the picture of our age.”[iv] But it is only an early picture. By the time you read this, will Google Maps and Android phones be replaced by something more advanced? Not unlikely.

What is Not Seen

Again, most people today have no idea this is happening. At least not at this scope, or pace. Many feel a general sense of a rising challenge, even a threat, from China, for example. But they don’t know what it means, why it is real, or how it is developing. They have no clue how to prepare for or address it.

The same is true of education. To wit: geography is still taught in two layers—much like it was in the 1960s. Technology makes it easier to teach and learn, but Layer Three tools and Layer Three thinking are absent in all but a very few out-of-the-box classrooms or learning environments. As Toffler put it, too many of today’s young are being raised to show up on time, do repetitive tasks without complaining, follow instructions, and memorize a great deal of knowledge without deeply understanding it. This is the focus of most schools.

These three lessons—punctuality, repetitive work, and rote memorization—routinely pass for what we call “education.” They are, in fact, the key lessons of schools in modernism. The pre-modern era emphasized “the 3 R’s: readin’, ’ritin’, and ’rithmetic,” and these prepared the young for success in the agrarian economy. Likewise, the three lessons above were often effective training for landing and keeping a job during the industrial age.

But today’s emerging information economy demands something different. Success now demands the Third Layer of education. It includes the kind of knowledge learned from the 3 R’s and also post-World War II schooling in history, literature, math, science, and social studies, but it also superimposes a Third Layer of education as well, which is more attitudinal and skills based: initiative, innovation, creativity, resilience, ingenuity, tenacity, recognizing opportunities, go-getter-ness, and entrepreneurial risk-taking.

The Third Layer is as different from most modern public and private schooling as the typical 1960s, 1980s, or 2000s high school or elementary was from the one-room schoolhouse. If the pre-modern age gave us Mary and Laura in the Little House series, studying at home or the local school (which was also the town hall, town theater, and community church), the modern age gave us the high school of Pretty in Pink, The Breakfast Club, High School Musical, Dead Poet’s Society, One Tree Hill, 90210, or even 22 Jump Street.

All are outdated now. All fail to prepare our nation’s youth for the actual economy of the 21st century. We are still training the young to succeed in a world they can only study about in history books. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to note that the more time they spend in the modern school system, including the increasingly outdated university campus, the less prepared they’ll likely be to compete effectively in the rough-and-tumble emerging global marketplace with its worldwide competition and demands.

All are outdated now. All fail to prepare our nation’s youth for the actual economy of the 21st century. We are still training the young to succeed in a world they can only study about in history books. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to note that the more time they spend in the modern school system, including the increasingly outdated university campus, the less prepared they’ll likely be to compete effectively in the rough-and-tumble emerging global marketplace with its worldwide competition and demands.

For example, a university degree isn’t what it used to be: The average graduate from the class of 2016 had $37,000 in student debt and couldn’t get a decent job in his or her field—or in any other equivalent field. There are of course exceptions, but the numbers of those leveraging college degrees into effective careers significantly decreases each decade (Note: in North America, Europe, and Latin America, but not in China). In short, today’s young adults are too often receiving a Layer Two education in a world that demands Layer Three knowledge, choices, and skills.

Past, Present, and Future

Few current students are being taught the skills of success that are needed in the new economy. The real economy. Layer Two schools simply do not teach initiative, ingenuity, or innovation. They don’t purposely teach chutzpah, audacity, grit, wise risk-taking, entrepreneurialism, or nerve.

Note that these are precisely the character traits that made America the world’s superpower. And Britain before her, and earlier, Spain and Portugal. These are the very traits that put Egypt at the top, then the Greek city states, and later Rome. These are the characteristics that gave the Gauls, Franks, Anglos and Saxons their edge.

They didn’t have Layer Three maps, to be sure, but they engaged in their era’s “Layer Three” education of the youth, teaching them the skills of resourcefulness, inventiveness, and daring in the face of difficulties. Some of these societies emphasized good purposes (such as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, etc.), while others embraced less noble goals (aristocratic rule of an elite class over the rest of the people, dominance over neighboring nations, a pursuit of wealth through violence, etc.).

But whatever their dreams—good or bad—it was Layer Three skills (initiative, boldness, pluck, enterprise) that lifted every great-power nation in history to the top. As the society that now holds this spot, we (North America, and to a lesser extent Europe) are stunningly lax about teaching these traits. We increasingly downplay them as unimportant and even unattractive. Even “against the rules”. As a result, we have lost our edge. We have largely lost our drive. Too many modern Americans have lost our shared vision and purpose. Unity is a thing of the past.

Indeed, Americans were once unified in the goal to spread freedom, opportunity, and prosperity to the world. Now, the best we seem to be able to muster is a hope to afford college for our kids, and that they’ll get a safe, secure career with good benefits—and as little fuss or struggle as possible. Most colleges themselves seem committed to shielding our young adults from challenges, difficulties, thinking, and any diverse or challenging ideas. This is not the behavior of a nation on the rise. It is the opposite. To paraphrase C.S. Lewis, we are castrating the stallions of the younger generations, then hoping they’ll be fruitful.

But apply Layer Three to the map. Where in the world do we find whole populations burning passionately with drive, initiative, innovation, nerve, entrepreneurial risk-taking, resilience, a hunger to achieve, audacity, ingenuity, resolve, and tenacity? Where do we find the largest concentrations of people who thrive in the face of uncertainty and embrace whatever is hard, and flourish even in an environment of impermanence and difficulty?

When you find a lot of people who have these traits, note where they live. Not in North American or Europe (at least not in large concentrations). In our modern American schooling/career system, for example, our major focus seems to be avoiding uncertainty, impermanence, and difficulty—yet these are the unavoidable realities of the global economy.

Through the Magnifying Glass

Look even closer. Enter this data electronically on a map and you’ll find these traits in China. Indeed, the heartbeat of China is a new “eye of the tiger.” A similar fire burns in India, and a less populated but angrier flame blazes across the Middle East. Layer Three also shows us the rise of such passion in parts of Latin America, Africa, and Russia. These are trigger-points of the decades just ahead.

Where such passion does show up in North America—from California to British Columbia, from Texas to New Hampshire to Newfoundland to Florida, it is usually personal, career-oriented, and commercial. A better job. A marketable education. A promotion.

These hardly match the resolve or intensity of China and its new economic allies across the developing world. They want to lead the world, change the world, and do great things. They want victory, and they see their lives as part of a battle.

In Europe the irony is even more pronounced. The Layer Three map shows numerous pockets of extreme passion in the nations of the E.U.—but zoom in, and you’ll note that most of the people with this kind of fire in the belly are usually recent immigrants from the Southern half of the globe.

The one great exception in North America and Europe is the entrepreneurial class, those who Steve Jobs called the dreamers, the rebels, and the risk-takers. They graduate from college and reject job offers from the Fortune 500 to pursue risky start-ups or launch non-profit charities. Or, increasingly, they skip college altogether, or drop out, and get started on their business or charitable ventures even younger, with an edgier, more idealistic and relevant education.

Their Layer Two parents and grandparents try to talk them out of such endeavors, but these young people have a hunger that typical education and careers won’t fill. They are a Remnant, throwbacks to the earlier Americans who got on the Mayflower, worked and died in Jamestown, went West by horseback or wagon to explore, start, create, and change things. They are the New American Founders, enlightened and ennobled by hindsight of the mistakes of the past, and impassioned by their view of the future – and we desperately need them.

We need a generation of them.

Now.

In the Now

If you are one of their parents or grandparents—worried that your youth are making such choices, decisions that make no sense to you—you can relax. Yes, the kind of risky leadership they are engaging is scary to the older generations who were raised to seek security. But the Third Layer maps clearly show that we no longer live in an era of security.

Even young people who follow the traditional path of college and career suggested by their elders will find that for most people it doesn’t endure in the new economy. We are in an era of tumult, change, and uncertainty—and this is only going to increase for the next few decades.

Those who try to live by Second Layer rules will fall further behind. College degrees won’t bring most of them secure jobs, and seemingly secure careers will suddenly be lost to recessions, new technologies, outsourcing, mergers, regulatory changes, companies sold to foreign investors, and competition, along with a host of other unforeseen realities.

Indeed, those who will do the best in the new economy—whose contributions and livelihoods will end up being the most secure—will be the new entrepreneurial class. The innovators. The roll-with-the-punches change agents. Those who can think, lead, initiate, and wisely assess risk. We are indeed entering the Age of Risk, and this massive shift in the world economy is here to stay. Business has already caught on and is changing things to meet the new reality. But education is still in denial, along with most in government.

Sadly for those who allow themselves to be swayed by the current denial of many in the educational sector and Washington, people caught in Second Layer thinking will be the losers of the next thirty years. The winners will be Third Layer risk takers who tenaciously create ways to succeed in the new environment. Who make a way.

Many of them are already looking at the world through the lenses of Third Layer maps and mindsets, and they understand something very real: The future is theirs. Moreover, our future is in their hands.

The more we can do to help and support them, the better things will turn out for all of us. The successes and failures of our entrepreneurs will determine the future. Just as it has determined the past.

Fall or Rise

This reality causes serious concerns. Anyone who takes a good look at the current university campus model of learning finds a number of problems. Not the kind of challenges that demand reform, mind you, but rather a systemic, structural network of problems that will require a true educational revolution. The need for change is, to put it lightly, drastic.

Just consider the following commentaries by some of today’s top thinkers on the topic of the emerging economy and its ties to the type of education we now need. For example, MIT’s Eric Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAffee wrote, in a section of their book labeled “Failing College”:

“Richard Arum and Josipa Roska…and their colleagues tracked more than 2,300 students enrolled full-time in four-year degree programs at a range of American colleges and universities. Their findings are alarming: 45 percent of students demonstrate no significant improvement on the CLA [Collegiate Learning Assessment, which tests ‘critical thinking, written communication, problem solving, and analytic reasoning’] after two years of college, and 36 percent did not improve at all even after four years.

“The average improvement on the test after four years was quite small…. What accounts for these disappointing results? Arum, Roska, and their colleagues document that college students today spend only 9 percent of their time studying (compared to 51 percent on ‘socializing, recreating, and other’), much less than in previous decades, and that only 42 percent reported having taken a class the previous semester that required them to read at least forty pages a week and write at least twenty pages total.

“They write that, ‘The portrayal of higher education emerging from [this research] is one of an institution focused more on social than academic experiences. Students spend very little time studying, and professors rarely demand much from them in terms of reading and writing.’

“They also find, however, that at every college studied some students show great improvement on the CLA. In general, these are students who spent more time studying (especially studying alone)…”[v]

The authors also wrote: “The good news, though, is that technology is now providing more…opportunities than ever before. Motivated students and modern technology are a formidable combination. The best educational resources online allow users to create self-organized and self-paced learning environments—ones that allow them to spend as much time as they need with the material, and also to take tests that tell them if they mastered it.”[vi]

Futures Past

The quality of learning in such online venues is very often extremely high. For example, when a graduate level AI course at Stanford was opened to participants on the Internet for free, over “160,000 students singed up for the course. Tens of thousands of them completed all exercises, exams, and other requirements, and some of them did quite well. The top performer in the course at Stanford, in fact, was only 411th best among all the online students. As Thrun [the instructor] put it, ‘We just found over 400 people in the world who outperformed the top Stanford student.’”[vii]

Likewise, “…Laszlo Bock, Google’s senior vice president of people operations, notes that college degrees aren’t as important as they once were. Bock states that ‘When you look at people that didn’t go to school and make their way in the world, those are exceptional human beings. And we should do everything we can to find those people.’ He noted in a 2013 New York Times article that the ‘proportion of people without any college education at Google has increased over time’—on certain teams comprising as much as 14 percent.”[viii]

Mindvalley founder and CEO Vishen Lakhiani wrote: “I’ve personally interviewed and hired more than 1,000 people for my companies over the years, and I’ve simply stopped looking at college grades or even the college an applicant graduated from. I’ve simply found them to have no correlation with an employee’s success.”[ix] Sadly, too many people still hold on to old educational models that no longer deliver what they once did, or what they now promise.

Mindvalley founder and CEO Vishen Lakhiani wrote: “I’ve personally interviewed and hired more than 1,000 people for my companies over the years, and I’ve simply stopped looking at college grades or even the college an applicant graduated from. I’ve simply found them to have no correlation with an employee’s success.”[ix] Sadly, too many people still hold on to old educational models that no longer deliver what they once did, or what they now promise.

Lakhiani put it this way: “But here’s the problem. Most of us are using systems that have long [since] become obsolete. As Bill Jensen said in his book Future Strong: ‘Even as we enter one of the most disruptive eras in human history, one of the biggest challenges we face is that today’s systems and structures still live on, past their expiration dates. We are locked into twentieth-century approaches that are holding back the next big fundamental shifts in human capacity.’”[x]

Bestselling author Neil Pasricha told the following story: “A senior partner at a prestigious global consulting firm once said to me after a boozy dinner: ‘We find Type A superachievers from Ivy League schools who need lots of reward and praise…and then dangle carrots just over the next deadline, project, and promotion, so they keep pushing themselves. Over every hill is an even bigger reward…and an even bigger hill.’”[xi] This is enlightening. It’s not the actual education the big corporations are looking for as much as a sense of over-achievement and needing lots of rewards and praise.

Look at this same scenario from the student’s viewpoint. Is this really the career environment we want our young people to pursue? Is this the life we want for them, or the use of their talents that will best benefit the world—or bring them the most fulfillment and happiness? Sometimes, the answer may be yes. But very often, it isn’t.

Billionaire Paypal co-founder and educational innovator Peter Thiel said it even more bluntly: “Higher education is the place where people who had big plans in high school get stuck in fierce rivalries with equally smart peers over conventional careers like management consulting and investment banking. For the privilege of being turned into conformists, students (or their families) pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in skyrocketing tuition that continues to outpace inflation. Why are we doing this to ourselves?”[xii] After happily reminiscing that he eventually took the entrepreneurial path of founding tech companies instead of following his major in graduate school, Thiel said[xiii],

“All Rhodes Scholars had a great future in their past.”

The Next Normal

The modern college/career system, which is increasingly Level Two education in the new economy, is more and more outdated. In the book Platform Revolution, technology experts Geoffrey G. Parker, Marshall W. Van Alstyne, and Sangeet Paul Choudary argue that the old-style university model is surviving largely because government regulations keep true innovators from competing on anything close to a level playing field.[xiv] If this were to change, no doubt online educational platforms would do for education what Amazon has done for bookstores (and other retailers), Uber has done for taxi services, Wikipedia has done to the encyclopedia publishing industry, and online news sources have done to many newspapers.[xv] Again, over 400 online students tested better than the top Stanford student in the exact same class.

Parker, Alstyne, and Choudary wrote: “The long-term implications of the coming explosion in educational experimentation are difficult to predict with certainty. But it wouldn’t be surprising if many of the 3,000 colleges and universities that currently dominate the U.S. higher education market were to fail, their economic rationale fatally undercut by the vastly better economics of platforms.”[xvi]

Just imagine much cheaper and higher quality higher educational offerings for all. Consider the work by Khan Academy,[xvii] Minerva,[xviii] Peter Thiel, and other educational innovators. If the government ever ends the current educational monopoly supporting the old-style conveyor-belt approach to higher education, the results will likely dwarf the kind of change we witnessed with the advent of cable television programs, or when Ma Bell was deregulated and replaced by an entirely different kind of telecommunications.

Parker and his colleagues also noted:

“In the years to come, the spread and increasing popularity of teaching and learning ecosystems will have an enormous impact on public school systems, private schools, and traditional universities. Barriers to entry that have long made a first-class education an exclusive, expensive and highly prestigious luxury good are already beginning to fall.

“Platform technologies are making it possible for hundreds of thousands of students to simultaneously attend lectures by the world’s most skilled instructors, at minimal cost, and available anywhere in the world that the Internet is accessible. It seems to be only a matter of time before the equivalent of a degree from MIT in chemical engineering will be available at minimal cost in a village in sub-Saharan Africa.

“The migration of teaching to the world of platforms is likely to change education in ways that go beyond expanded access—important and powerful as that is. One change that is already beginning to happen is the separation of various goods and services formerly sold as a unit by colleges and universities. Millions of potential students have no interest in or need for the traditional college campus complete with an impressive library, a gleaming science lab, raucous fraternity houses, and a football stadium.”[xix]

They’d rather pay a lot less and get a better learning experience.

Focusing In

“Education platforms are also beginning to unbundle the process of learning from the paper credentials traditionally associated with it.”[xx] The authors note that many students now “…appear to be more interested in the real-world abilities they are honing than in such traditional symbols of achievement as class transcripts or a diploma.”[xxi] They want to learn knowledge and skills that help them achieve their life and financial goals, not traditional symbols that no longer really work in the 21st century economy.[xxii] Results-Based Learning is increasingly in demand.

For example, “A high ranking on TopCoder, a platform that hosts programming contests, will earn a developer a job at Facebook or Google just as fast as a computer science degree from Carnegie Mellon, Caltech, or MIT. Platform-based students for whom a traditional credential is important can often make special arrangements to receive one—for example, at Coursera, college credit is a ‘premium service’ you pay extra for.”[xxiii] Another example is Duolingo, a crowdsourcing foreign language platform that is teaching more people a foreign language than all the students studying foreign language “in high school in the U.S. combined.”[xxiv]

“Once there is an alternative certification [to college degrees] that employers are willing to accept,” Parker and his colleagues affirm, “universities will find it increasingly difficult…. Unsurprisingly, developing such an alternative certification is among the primary goals of platform education firms such as Coursera.”[xxv] Other organizations are trying to build such educational platforms as well, including Udacity, Skillshare, edX, and others.[xxvi] Even top specialty schools, like MIT and Julliard, are offering open enrollment online courses. (Their selling point is often focused on “Learn from the MIT faculty,” or “Learn from the Julliard faculty,” a nod to the new reality that mentoring is becoming even more important than institutionalism.)

No doubt more innovative higher educational options will thrive (and at the high school level as well), until some of them restructure modern education like eBay, Amazon, Facebook, Uber, the Internet, or Google have done for other fields. As far as student learning is concerned, numerous self-produced online tutorials, on platforms like YouTube and others, provide excellent educational opportunities—both to learn and teach.

All of these developments and trends are part of Third Layer education, and they are almost universally moving away from outdated traditions, methods, and beliefs of conveyor-belt-style education and schools. A new economic era is already here, and for those who know what to look for, new educational models are rising to support what is now needed. Third Layer, Results-Based learning is the future of effective education. The focus is on individualized learning, thinking, and applying rather than conveyor-belt schooling.

The new maps are here, if we’re willing to look.

(This topic is addressed in more detail in Hero Education by Oliver DeMille, available here>>)

[i] Parag Khanna, 2016, Connectography, xvii.

[ii] Harper’s Index, Harper’s Magazine, September 2015.

[iii] The Brexit and election of Donald Trump didn’t seem to make much difference in this trend. See, for example, Geoffrey Smith, “The Brexit Crisis That Wasn’t,” Fortune, October 1, 2016; See also, Jeff Immelt, “After Brexit, Global is Local,” Fortune, August 1, 2016, 71-72.

[iv] Joshua Cooper Ramo, 2016, The Seventh Sense, 122.

[v] Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, 2014, The Second Machine Age, 197-198.

[viii] Cited in Vishen Lakhiani, 2016, The Code of the Extraordinary Mind, 24.

[xi] Neil Pasricha, 2016, The Happiness Equation, 150.

[xii] Peter Thiel, 2014, Zero to One, 36.

[xiv] See Geoffrey G. Parker, Marshall W. Van Alstyne, Sangeet Paul Choudary, 2016, Platform Revolution, 263-268.

[xvii] For example, see commentary in Brynjolfsson, 199.

[xviii] For example, see commentary in Parker, 268.

[xxvi] See, for example, ibid., 265.

Category : Blog &Business &Citizenship &Community &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Education &Entrepreneurship &Generations &Government &History &Independents &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Mini-Factories &Mission &Politics &Producers &Prosperity

The Jefferson-Madison Debates: The Next Civil War?

May 13th, 2018 // 4:25 pm @ Oliver DeMille

True or False…or False?

It’s getting worse. Just watch the news. This phrase, the “Next Civil War”, was recently used by economic forecaster Harry Dent to describe the growing divide between Red and Blue state cultures. These two sides now disagree with each other to the point that in many cases people experience real hatred for those on “the other side”.

It’s getting worse. Just watch the news. This phrase, the “Next Civil War”, was recently used by economic forecaster Harry Dent to describe the growing divide between Red and Blue state cultures. These two sides now disagree with each other to the point that in many cases people experience real hatred for those on “the other side”.

Former president Barack Obama noted that people who largely get their news from the mainstream media and those who get their news mostly from Fox are basically living “on different planets.” They not only disagree on principles and solutions, he pointed out, but they fundamentally disagree on “facts”. What the Blue culture sees as incontrovertible truths, the Red culture frequently sees as lies. Fake. False. And the opposite is just as true: what the Red culture sees as fact is often considered false by Blue culture.

No wonder the two sides are so angry at each other. When you disagree on what the facts are, the solutions promoted by the other side frequently appear ludicrous. Even dangerous. Both sides, each rooted in its own understanding of reality, watch the other side say and do things that are clearly and painfully hurtful—according to the set of obvious but differing “facts” they each believe.

Roadblocks

This divide is widening. We’ve reached the point that one of the worst things parents can learn about their child’s “significant other” or new fiancé is that he/she is a Republican, or Democrat—depending on the family. Religion, career, ethnicity, education, financial status, and even a criminal history, are largely negotiable in most modern families. But the other political party? Many parents turn Tevye: “If I try and bend this far, I’ll break.”

Lynn Vavreck wrote in The New York Times (January 31, 2017): “In 1958, 33 percent of Democrats wanted their daughters to marry a Democrat, and 25 percent of Republicans wanted their daughters to marry a Republican. But by 2016, 60 percent of Democrats and 63 percent of Republicans felt that way.” And for many, the feelings run very deep. While in 1994 21 percent of Republicans viewed Democrats in the “Very Unfavorable” category, by 2016 the number was 58 percent. (Pew Research Center) In 1994 17 percent of Democrats saw Republicans as “Very Unfavorable”, but the number in 2016 had skyrocketed to 55 percent. (Ibid.)

Aaron Blake summarized this concern in The Washington Post: “If 58 percent of Republicans hate Democrats and 55 percent of Democrats hate Republicans, that would mean about 35 percent of registered voters hate the opposite political party.” (June 19, 2017) “But that’s not quite hate…. 45% of Republicans see the Democratic Party as a threat to the nation’s well-being…. [and] 41% of Democrats see the Republican Party as a threat to the nation’s well-being”. (Ibid.) When you add independents, the “hate” one of the parties (those who see the other party as a threat to the nation) makes up 39 percent of registered voters or “About 1 in 4” Americans. (Ibid.)

There are a lot of others who see the other side in an unfavorable light, around 33 percent of additional Republicans (for a total of 91% with “unfavorable” or “very unfavorable”) and 30 percent of additional Democrats (86% with “unfavorable” or “very unfavorable” views). (Ibid.) Note that all of this occurred before the Trump presidency. Again, this divide is real, and deep. In the Trump era the intensity has only increased.

But does any of this justify the phrase “Next Civil War”? Not yet. Not unless we’re going to surrender to hyperbole. Yet this conflict is escalating in many sectors—it’s moved beyond the traditional battlegrounds of politics and news media to additional culture and power centers including education, television, movies, entertainment awards shows, daily and nightly talk shows (both radio and television), sports, and multiple venues on social media. Even social media and Internet platforms are getting involved by adjusting algorithms to promote certain political leanings—or dampen the voice of those they dislike—often without informing their customers.

Platforms and Soapboxes

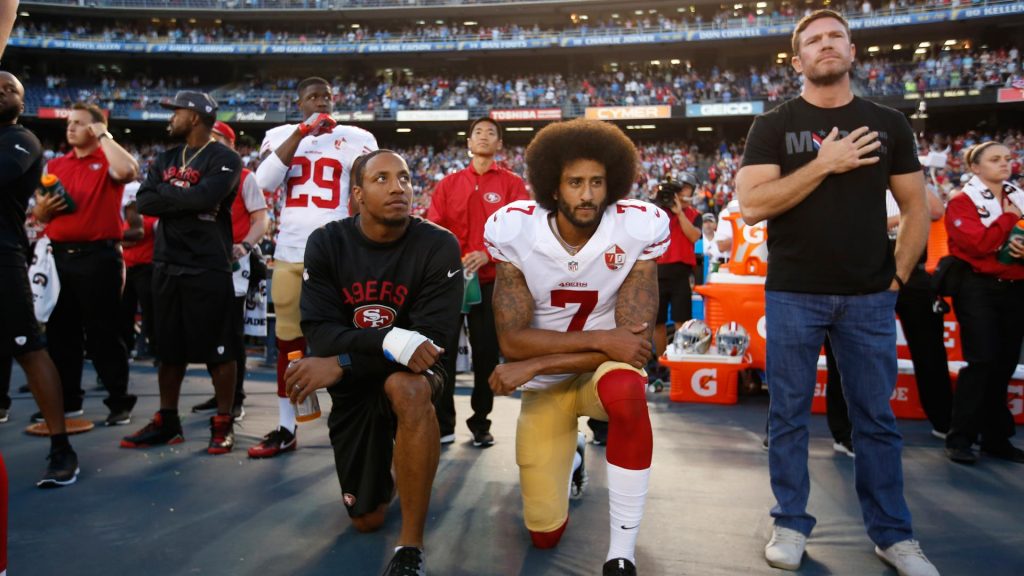

For many Americans, the sight of some NFL players purposely kneeling during the National Anthem is the ultimate symbol of this divide. One side sees young role models and leaders using their public platform to bravely protest government abuse—especially what they consider racially charged police violence. The other side feels hurt and confused by millionaire beneficiaries of the American Dream figuratively spitting on the American Flag and the sacrifice of dead and maimed military heroes.

For many Americans, the sight of some NFL players purposely kneeling during the National Anthem is the ultimate symbol of this divide. One side sees young role models and leaders using their public platform to bravely protest government abuse—especially what they consider racially charged police violence. The other side feels hurt and confused by millionaire beneficiaries of the American Dream figuratively spitting on the American Flag and the sacrifice of dead and maimed military heroes.

It’s difficult to even discuss this situation rationally in many venues due to the raw and heartfelt emotions of people on both sides of the Red-Blue cultural divide.

Sadly, many schools have also become places of great conflict. For example, a national uproar occurred when a middle school teacher assigned her students to write letters to political officials urging them to pass stronger gun control laws. Should teachers tell middle school children what sides to take on political issues? And assign them to engage in activism for one specific side? At what point does teaching become brainwashing? A father of one of the students, a policeman, refused to allow his child to do the assignment. The father deeply disagreed with the politics of the teacher, and many of the other parents disagreed with the politicization of middle school in general. In response to backlash, the teacher allowed students to skip the assignment without penalty, but didn’t suggest writing against stronger gun control if this more accurately aligned with the student’s views. The same week, an elementary student was expelled from school for drawing himself hunting during a “free art” assignment, and a high school teacher was fired for a lengthy history-class soliloquy describing current members of the military as “the lowest of the low” in our society. Red and Blue cultures passionately disagreed on how these events should be handled. Both sides largely see the other’s view as ridiculous and extreme.

Another moment that epitomizes this division occurred on Broadway when the cast of Hamilton stopped the musical midstream to lecture the new Vice President elect, Mike Pence. Hamilton itself is an artistic icon—an American Les Miserables that underscores how the struggles of Washington, Jefferson, Hamilton and their families and peers unleashed freedom in a way that has now spread to people of all backgrounds. The lecture itself was seen by one side as a welcome comeuppance to a dangerous new administration, and by the other as yet another gauche elitist attack against the will of the voters and the American system.

Networks, Numbers, and New Divides

Thankfully this war is largely cultural—it has not devolved into massive physical violence between the two sides of a nation (like the French Revolution, U.S. Civil War, or Russian Revolution, etc.). Hopefully it will always remain peaceful. But in the fight for hearts, there is no doubt that a major civil war for the future of our republic is already under way.

Thankfully this war is largely cultural—it has not devolved into massive physical violence between the two sides of a nation (like the French Revolution, U.S. Civil War, or Russian Revolution, etc.). Hopefully it will always remain peaceful. But in the fight for hearts, there is no doubt that a major civil war for the future of our republic is already under way.

Worse, it is doubtful that any real solution is imminent. When one part of the nation generally believes most of what airs on CNN, ABC, NBC and MSNBC, while another part tends to place more trust in Fox News, Rush Limbaugh, or Trump tweets, the two aren’t going see eye-to-eye on much of anything. And when these two groups are the largest political blocs in our republic, we’re going to have genuine and repeated disagreements.

Perhaps the epicenter of this battle for “the hearts and minds of the people” is found in the media. And this poses a major challenge. Why? Because most of modern media—from both the Left and Right—has three serious problems:

1-It is largely agenda driven (“Forget the facts, full speed ahead!”)

2-It is shallow.

3-It is electronic.

Most people realize the problems with item #1. As a result, they stop listening to media outlets that are clearly against their views—and seem hostile to anyone with a different perspective. This has created another significant problem with modern media:

4-It is isolated. The Right listens to the Right, while the Left listens to the Left. Few listen to both. Few listen to the other side. Over time, media outlets increasingly cater to their narrow audiences, so the extremism increases.

Result: the divisions in our nation are getting wider, deeper, and more susceptible to anger and, too often, extremism and unhealthy thinking and actions.

The Missing Depth

The 2nd and 3rd problems listed just above are equally dangerous. Many people are very busy—work, family, more work, community, more family. Little time is left over for meaningful civic involvement, much less for taking the time to really dig into each day’s news, truly understand what is happening, and go way beyond the 30 second sound bites or even 3 minute segments on any given story. An hour of the news is more than most can spare—and most hour newscasts only provide a very shallow overview of a few of the day’s news topics. In short, shallow. No time for depth.

The 2nd and 3rd problems listed just above are equally dangerous. Many people are very busy—work, family, more work, community, more family. Little time is left over for meaningful civic involvement, much less for taking the time to really dig into each day’s news, truly understand what is happening, and go way beyond the 30 second sound bites or even 3 minute segments on any given story. An hour of the news is more than most can spare—and most hour newscasts only provide a very shallow overview of a few of the day’s news topics. In short, shallow. No time for depth.

The result is that nearly all shows repeat a few top stories, with only a bit of detail. Even if a person watched television all day, he or she would usually only hear about the same top stories, addressed shallowly over and over—with different opinions but nothing really weighty or reflective. Depth is almost unheard of in most of today’s media.

This is especially true of the electronic media. Besides, television, radio, and online media typically interact with human brains more like entertainment than like something really, truly important. When we watch or listen or surf our news, in most cases, we are in the mode of moving quickly from one thought to the next. Even if we try to focus, ads, pop-ups and crawlers invade our screen with multiple headlines and distractions all at once. Our devices were purposely designed this way, in fact.

Reading the news, in contrast, naturally moves the focus into our intellect. A good start. “But nobody wants to read anything longer than a page…” today’s editors assure everyone. Many editors put the limit at “two paragraphs.” If we don’t read more deeply, we’ll truly and literally become a nation of sheep. Deep thinking is needed to deal with the reality of today’s complex and globally-interconnected world—for any citizen. And deep thinking about the news is basically impossible unless we’re reading (or listening/watching to a source that takes) much more than 5 minutes to really address an issue in some depth.

The Jefferson-Madison Debates

The term “fake news” means the following to most people: news that pushes a false agenda, distracts from truth, lies. But “shallow news” is just as bad for the nation. Even “accurate news” that is shallow is a major blow to our society. And this accounts for most of what media consumers experience. When it is both fake and shallow, we’re in real trouble.

The Left and Right argue about which news reports are “fake,” but few even claim to offer real depth in their news. And even fewer consumers seem to be actively searching for and embracing deeper news.

To reiterate: the Red-Blue divisions are growing, and intensifying, and this means that major problems are ahead unless we do something about it. My plan is to write a weekly (or, sometimes, every two week) article that treats real topics in enough depth to help readers take a step back from the constant screaming of electronic news, and really understand a topic (one at a time) enough to see behind the scenes of modern media spin and fake/shallow posturing.

More will, of course, be needed to stop our seeming national sprint toward more civil conflict. But I know this weekly column will make a difference—for those who read it.

More will, of course, be needed to stop our seeming national sprint toward more civil conflict. But I know this weekly column will make a difference—for those who read it.

It was the reading and thinking about articles and pamphlets during the American Founding generation that helped America gain freedom, and deep thinking is vitally needed today. I’m calling this new series of weekly articles The Jefferson-Madison Debates, and I hope you’ll join us.

It’s going to be fun.

— Oliver DeMille

(RSS Feed sign up here ***)

Category : Aristocracy &Arts &Blog &Business &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Education &Entrepreneurship &Generations &Government &History &Independents &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Politics &Producers &Prosperity &Statesmanship &Technology

The Jefferson-Madison Debates: Are Today’s Education and Politics Entering the Age of Star Trek?

May 12th, 2018 // 9:02 am @ Oliver DeMille

“A shoe, too, is no longer a finished product, but an endless process of reimagining our extended feet, perhaps with disposable covers, sandals that morph as you walk, treads that shift, or floors that act as shoes.” —Kevin Kelly

“We have long argued that as the Web extends in usage…increased access to factual information would improve the quality of public discourse. However, the opposite seems to be occurring.” —Don and Alex Tapscott

Given how much technology has changed the world in the past twenty years, and how differently we now live, it’s easy to assume that the Internet Revolution has brought the big change—and this era of massive shifts will slowly relax back into some kind of normality. But the truth is that we are just at the very beginning stages of the Information Age. The changes have just begun.

Given how much technology has changed the world in the past twenty years, and how differently we now live, it’s easy to assume that the Internet Revolution has brought the big change—and this era of massive shifts will slowly relax back into some kind of normality. But the truth is that we are just at the very beginning stages of the Information Age. The changes have just begun.

Following are a few of the major developments still ahead, as described by the experts on current technologies. As you think about each of these, consider the ramifications of these trends as they relate to the future of education, career, the economy, and the type of education needed for the emerging economy:

1. Autonomous vehicles. Self-driving cars are a reality.[i] How long they will co-exist with human drivers before the laws require all cars to be driven electronically remains to be seen.[ii] Self-driving planes, boats, and trucks will also change our lives drastically. Flying vehicles are next. As drone technology improves, taking people as passengers may not be too far away.

2. 3D Printing (additive manufacturing).[iii] This will revolutionize transportation, shipping, and manufacturing. Things that can be printed out in our own homes don’t need to be built in factories, or shipped by truck, airplane, or even drone. 3D printing will also have significant impact in medicine by printing certain medical implants.[iv] In fact, 3D printers now print food, including candy—and some people think it even tastes good.[v] One taste tester wrote: “It tastes like an after-dinner mint mixed with a sugar cube.”[vi]

3. 4D Printing. The printers will print smartobjects that are self-learning, and self-altering in response to their environment.[vii]

4. New Smart Materials. As Klaus Schwab, Founder of the World Economic Forum, put it: Some are “self-healing, self-cleaning, metals with memory that revert to their original shapes, chemicals and crystals that turn pressure into energy, and so on…. Take advanced nanomaterials [nano means smaller than the human eye can see] such as graphene, which is about 200-times stronger than steel, a million times thinner than a human hair, and an efficient conductor of heat and electricity. When graphene becomes price competitive…it could significantly disrupt the manufacturing and infrastructure industries.”[viii]

5. iMoneyCenter. As Forbes put it: “Your cellphone will become a global bank. Mobile money accounts already outnumber traditional bank accounts in parts of the developing world, and new technology will turbocharge that trend, allowing payments to anyone, anywhere, in local currencies.”[ix]

6. RFID (Radio Frequency Identification). Tiny tags can be put on pretty much anything, or anyone, and track where it is at any time, all over the world.[x] This technology is cheap and easy to use. The tags can even contain sensors that keep track of how well the item is doing, and what it is doing.[xi]

New Normal

Kevin Kelly said of the various kinds of small digital devices that are being created: “A few are shrinking to the size of the period following this sentence. These macroscopic measurers can be inserted into watches, clothes, spectacles, or phones, or inexpensively dispersed in rooms, cars, offices, and public spaces.[xii] Sensors can be built to watch and listen.” He also wrote: “Massive tracking and total surveillance are here to stay.”[xiii]

The machines are becoming ubiquitous.[xiv] Moreover, a lot of people like it this way. One report summarized the trend as “Our Love-Hate Affair With AI.”[xv]

The ramifications of the new era of machines for freedom and relationships of all kinds are immense.[xvi]

7. Gene Mapping and Synthetic Biology. This is popularly called the creation of “Designer Babies.” “It will provide us with the ability to customize organisms by writing DNA.”[xvii] “Today, a genome can be sequenced in a few hours for less than a thousand dollars.”[xviii] And at some point scientists foresee artificial memory implanting into peoples’ brains.[xix] Just download what you want to know—facts, dates, formulas, etc. Gene Mapping will impact agriculture and the energy sector (by producing biofuels) as well as medicine and education.[xx]

8. Personalized Medications. Medicine, from those used to treat advanced diseases to simple aspirin, will be personalized for each individual—“tailored to your DNA.”[xxi] These will likely be very expensive at first, further widening the gap between the upper and other classes.

9. Non-Communicative Relationships. A number of popular magazines each month present articles that tell men and women they need to turn off their electronic gadgets and talk to their spouse or significant other. The articles are detailed and specific, with advice like “look your spouse in the eye while you talk to her,” and “actually listen to the words he says and try to connect with his logic and feelings,” etc.

The volume of such articles suggests that this is a serious problem. Relationships are often victims of addiction to electronic devices, texts, messages, and other incoming communication that is more highly valued than interaction with the live person in the same room.

Relationships and Roboticships

Moreover, emerging technology will very likely throw a serious monkey-wrench into many relationships. VR (Virtual Reality[xxii]) is incredibly advanced now, and will soon be on the market in extensive ways. A person can slip on a VR helmet or glasses and be transported mentally to a whole new world. Some VR research and development is focused on porn, although the tech world prefers the term “alternative relationships.” How will this impact marriage, family, education, and stable relationships?

Robotics have reached the point that lifelike “partner dolls,” sometimes called “sex dolls”, that talk and interact are already available.[xxiii] Soon, experts say, they’ll be easily accessible online and sold in our corner neighborhood stores.[xxiv] It’s a potential revolution in lifestyles, and the impact on relationships will certainly be real.[xxv] It is unclear how this will influence marriage and family, but the prospects seem quite negative.

A number of apps try to fulfill the same need—for relationships in an electronic format.[xxvi] If we find it difficult now to put down our phones or take off our headphones to engage in meaningful conversation and relationships, imagine how difficult it will be to turn off the robots, apps, and VR glasses.[xxvii] VR, and lifelike personal relationship robots, can be programmed (or told by the user) to never argue, nag, disagree, shout, or storm away.[xxviii] Again, such devices won’t take the place of quality, mature relationships, but they could very well hurt or make such relationships more difficult.[xxix]

10. The Rise of the Algorithms. Online technology now employs numerous advanced algorithms and AI technologies that are learning to do everything from sensing where our eyes are gazing (in order to know our interests and sell to us)[xxx] to what our politics are (as mentioned above, this could be to allow providers like Facebook and Google, or others, to determine what news feeds to send us—to promote their own political goals), to how empty the milk carton in our fridge is (in order to order a fresh one).

Schwab said: “Amazon and Netflix already possess algorithms that predict which films and books we may wish to watch and read. Dating and job placement sites suggest partners and jobs—in our neighborhood or anywhere in the world—that their systems [algorithms] figure might suit us best.

The Man AI in Charge

“What do we do? Trust the advice provided by an algorithm or that offered by family, friends, or colleagues? Would we consult an AI-driven robot doctor with a near perfect diagnosis success rate—or stick with the human physician with the assuring bedside manner we have known for years?”[xxxi]

AI is tasked with watching us and learning from us, and as AIs become smarter, some of them will be incredibly effective forecasters. Companies may even be valued based on their AI. For example, Kelly wrote: “Amazon’s greatest asset is not its Prime delivery service but the many millions of reader reviews it has accumulated over the decades.”[xxxii] These reviews, and the AI that runs them, learns from them, and uses them to help predict what books each user is likely to enjoy, is a huge asset.

The concept of establishing corporate boards of directors made up entirely of Artificial Intelligence is discussed openly and seriously.[xxxiii] Do we want algorithms in charge of everything?

In education, the possibilities are seemingly endless—and just as alarming. Kelly wrote: “The tiny camera eyes that now stare back at us from any screen can be trained with additional skills…researchers at MIT have taught the eyes in our machines to detect human emotions. As we watch the screen, the screen is watching us, where we look, and how we react.

“Since this perception is in real time, the smart software [algorithms] can adapt what I’m viewing. Say I am reading a book and my frown shows I’ve stumbled on a certain word; the text could expand a definition.”[xxxiv]

This means that the text of the book is changing before you read it, based on what you have read so far and how you reacted. In other words, the computer is in effect censoring what you read before you even read it.

What about the author’s intent? Well, that depends. The AI, or the people who commission and oversee the AI, may decide to carefully protect the original text, or they may not. They may edit, censor, distract, etc.—whatever they think best achieves their goals.

Remember that thing called Thinking?

They may even have different ways of dealing with different people—like Google gaming the search system so that people who look up a certain Republican candidate get the most negative articles about him on the first page, while those who search for his Democratic opponent get the most flattering articles (or vice versa).

Or they might simply guide your searches to the companies who paid them the most to do so. If these guides are personalized and targeted to each individual user (like in the movie Minority Report), different readers will literally be getting a very different education. One student will read very different things than a second student, while the third reads yet another thing—all determined by AI and/or those who program and control the AI.

Kelly continued: “Or, if it realizes I am reading the same passage, it could supply an annotation for that passage. Similarly, if it knows I am bored by a scene in a video, it could jump ahead or speed up the action.”[xxxv] If we choose such functions on a menu, that’s one thing. But what happens if the big businesses or the cyber-governmental-industrial-complex just decides that this kind of censorship is best for the people? Or for a certain group or type of people, such as those from a certain religion or political party?

On purely educational grounds, having the computer supply definitions, commentaries and links is bad for thinking. It teaches rote dependence on experts, even if the expert is an AI. If we don’t have to question, ponder, or debate the books we read, we’ll be thinking a lot less. The words censorship and brainwashing aren’t farfetched in this context.

What about politics? The media and party-media machines already spread a lot of false information. What will happen when algorithms take over the media spin? It will personalize to each reader, each person using the Internet (or whatever kind of Supernet or Skynet takes its place). As such, the AI will learn how to confuse each person the most effectively. Again, this isn’t far from the personalized billboards and ads in the movie Minority Report.

(Un)Locked Doors

On an even larger scale, if an algorithm claims to predict which of various candidates would make the best president, prime minister, judge or senator, do we just give up voting altogether? After all, the voters seldom put in leaders who truly deliver what they promised. Or will the experts try to convince us that an algorithm-based AI should be our president and Congress and Court and make our top government decisions—getting rid of human error altogether?

And in all this, let’s not forget that someone can access the algorithms. All computers can be hacked—so far. As author Marc Goodman put it: “There’s never been a computer system that’s proven unhackable.”[xxxvi] Bigger technologies mean bigger hacks, with more drastic impact on people.

And won’t the growth of the Internet just funnel more and more power to a few elites who control the algorithms? The answer is “Yes. Emphatically yes!”

In fact, is there any way to stop this from happening?

11. “Reshoring.” This means that when high tech processes like 3D printing, gene mapping, and RFID tagging become mainstream around the world, many industrial jobs will be lost—but a lot of high-tech jobs will move back to the most advanced nations in search of highly-trained workers with expertise in areas conducive to high tech.[xxxvii] Whether this will happen or not remains to be seen. It may not happen at all. “…many workers [may]…end up permanently unemployed, like horses unable to adjust to the invention of the tractors.”[xxxviii]

12. Portfolio Careers. These occur where a person’s career includes doing several different jobs for different employers in the same day.[xxxix] For example, one person might be a teacher during the school day, a restaurant manager during the evenings, and an eBay seller in his spare time—all to make ends meet. Portfolio careers may become very widespread in the new economy. A lot of people probably won’t like such a development, leading to increased class divisions and conflicts.[xl]

13. Even Greater Class Divide. As Schwab wrote: “…half of all assets around the world are now controlled by the richest 1% of the global population, while the lower half” of the population control less than 1% of world assets.[xli] Or as the Tapscotts put it: “…the global 1 percent owns half of the world’s wealth while 3.5 billion people earn fewer than 2 dollars a day.”[xlii]

To be continued next week …

[i] Schwab, 15, 147-148; see also Kevin Kelly, The Inevitable, 2016, 50-51; Brynjolfsson, 14-20; See Sam Smith, “The Truth About the Future of Cars,” Esquire, April 2016, 69-74; Erin Griffith, “Disconnected,” Fortune, August 1, 2016, 44.

[ii] See Smith, 69-74.

[iii] Scwhab, 15; see also Brynjolfsson, 36-37; Kelly, 53.

[iv] Schwab, 15, 22, 161-167.

[v] Andrea Smith, “Print Your Candy and Eat it Too,” Popular Science, January 2015, 24.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Schwab, 16.

[viii] Ibid., 17.

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Education &Entrepreneurship &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History &Independents &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Politics &Postmodernism &Producers &Prosperity &Science &Technology

One Great Challenge Facing America Today

August 26th, 2017 // 4:51 am @ Oliver DeMille

The Coming Fall

Only 15 percent of Americans are on target to fund 1 year or more of their retirement. One single year. Yet many will live twenty to thirty years after retiring. This one fact alone is a major blow against conservatism.

Only 15 percent of Americans are on target to fund 1 year or more of their retirement. One single year. Yet many will live twenty to thirty years after retiring. This one fact alone is a major blow against conservatism.

It may in fact kill conservative principles and ideals in the next two decades, and it could deeply hurt the American economy and our freedoms in the process. This is not an exaggeration. Put simply:

How can conservatives expect to win elections or, even if they are victorious at the ballot box, actually pass conservative laws and policies when more than 85 percent of the American people are going to be fully dependent on someone else’s money for housing, food and clothing, health care, and other expenses during retirement?

With the massive Baby Boom generation moving into retirement, many analysts ask: how can the United States implement anything short of collectivist socialism in the next thirty years?

To cut away the safety net, or to default on the promised Social Security and healthcare benefits workers paid into for decades, would be immoral and create widespread poverty for many of our most vulnerable. To buck up and pay for these obligations, and supplement them with what will be needed for millions of retirees to just get by, will require levels of taxation and regulation that will truly be nothing short of…well, socialism.

Bottom Dollar

Few people want to admit this reality—Republican politicians least of all. But over sixty years of government promises, spending money that should have been saved, inflating the currency, and putting numerous regulatory hurdles in the path of entrepreneurialism, innovation, and economic growth have taken their toll. A national debt north of $20 trillion dollars (more than $100 trillion when all the obligations and liabilities are met, and a lot more as these obligations and interest on the debt increase every month) leave us little wiggle room.

There are two realistic responses. First, we can go after major economic growth. This will require a systemic change in our economy—meaning mass deregulation and getting the government almost entirely out of the marketplace. Tax rates must come down drastically, and foreign-held corporate money must be encouraged to repatriate without penalty. Foreign direct investment must also be recruited (another reason tax rates must be significantly reduced).

The second option is to keep on the current path until we default, then allow an IMF bailout of the U.S. and the replacement of the dollar as the world reserve currency with International Monetary Fund SDR currency or some other (probably electronic) legal tender. This will result in a major reduction of the standard of living for most Americans and an explosion of additional government handouts. Most retirement and other savings that do exist will be wiped out, and nearly all Americans will go on the dole, with a few elites at the top, and both socialism and globalism will dominate.

The amazing thing, to me at least, is that many of our nation’s leaders right now—in both parties—actually prefer the second option. Moreover, a lot of them believe that this is the best course for our future. They deeply believe in globalism, collectivist economics, and the end of America’s attachment to free enterprise, gun rights, family values, and religion. They believe that government is the greatest power on earth, and deserves our universal allegiance and support. Even, ultimately, reverence. Anyone who disagrees, they believe, is small-minded or caught in the past—or both.

New or Old

Not only do many Democratic leaders hold this view, but a surprising number of Republican officials believe it as well, or at least they vote like they believe it (which brings the same results). This is a real battle, and the globalist elites are winning. The media, most of academia, and a majority of politicians are on their side. In their view, the future of the world is at stake—either a bright future of globalism (with elites in charge) or a return to dark-age tribalism, as they see it (where the regular people rule through small-minded, unenlightened democratic influence), will ensue. They are determined to ensure the globalist outcome.

They literally consider it a war–and one that is worth winning, whatever the cost. If academia, media, Hollywood and the lobbyist/D.C. bureaucracy/political party-apparatus can force the Trump administration to back down from anti-globalist policies and behaviors, so be it. That’s what the hubbub is about on the nightly news, investigations, etc.

But if not, they’ll take more drastic measures. A currency default might do it, causing bank holidays and massive layoffs. Or a serious shakeup in the White House—brought on by the Special Counsel, indictment of the President, or something else that circumvents the will of the voters and instead chases the goals of the elite. Something unexpected, of the same magnitude, could trigger a return of White House alignment to globalist goals. Today’s elites in government, media, finance, etc. can hardly remember a time when globalism wasn’t the clear agenda. Most of them are outraged at the very thought.

The rest of America has a serious problem. Remember the 85 percent of Americans who don’t (or won’t) have enough retirement savings to last more than a year? How are conservatives going to effectively promote smaller government and a return to genuine free enterprise in a nation strapped with the $20 trillion-plus national debt, $13 trillion in consumer debt, over $100 trillion owed in debt plus unfunded liabilities, and many millions (and growing) of retirees who will desperately need financial support?

The Next Step

I’m an optimist, because I believe the best days of America and the world are yet to come. Usually I infuse my writings with optimistic ideas on how we can really improve things in the days ahead. But right now I have to admit that I’m concerned. I’m not sure how we get past the economic hole we’ve dug for ourselves—not just politicians, but the regular people as well. We are culturally, if not actually, dependent on government spending and government growth.

Yes, a lot of people want the government to cut back, but they can’t agree on what to cut. Almost all Americans want the government to keep spending for things that benefit them directly. The ones that support cuts mostly only support cutting other people’s government benefits. Thus Congress doesn’t actually fix much.

Unless this changes, Democrats will continue to be the party of bigger government and increased socialism while Republicans will talk about smaller government, limits, and Constitutional boundaries—but when the votes come to the Senate, truly conservative changes won’t have enough Republican support to pass, and when cases make their way to the Supreme Court, free enterprising systemic changes to the government-corporate-K Street nexus won’t have enough Justices behind them. Too many officials simply aren’t willing to do what needs to be done. It’s too hard, and too unpopular.

I’m not sure what can change this.

Of one thing I am certain, however. History is absolutely clear on this point. As goes entrepreneurship, so goes our nation. Ultimately, a major increase in effective entrepreneurship, innovation, and business ownership is going to make or break us. It will create growth if it happens, and that changes everything. Also, the future of entrepreneurship is something each of us can influence. Our next three decades will either bring massive economic growth or the rise of rampant socialism to America. To choose the path of growth, our government can help (by deregulation and choosing to be smaller)—but a lot more people engaging effective entrepreneurship is the indispensible. Period.

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Entrepreneurship &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History &Leadership &Liberty &Mini-Factories &Mission &Politics &Postmodernism &Producers &Prosperity