Ron Paul Is the Winner in 2015 by Oliver DeMille

September 18th, 2015 // 7:14 am @ Oliver DeMille

Why the Republican Establishment Is Surprised

(and a bit clueless)

by Oliver DeMille

Shock and Awe

The current presidential election has left most of the Establishment speechless. They are shocked by the rise of Bernie Sanders, shocked by the success of Donald Trump in the polls, and shocked by the popularity of Ben Carson. “Shocked” may actually be too weak a word. Apoplectic, maybe?

The current presidential election has left most of the Establishment speechless. They are shocked by the rise of Bernie Sanders, shocked by the success of Donald Trump in the polls, and shocked by the popularity of Ben Carson. “Shocked” may actually be too weak a word. Apoplectic, maybe?

The Establishment is also surprised by the struggles of Hillary Clinton, Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, and Scott Walker—all of whom were widely predicted to dominate this election cycle.

“Why is this happening?” is a popular question on many political news programs right now. Along with: “Will it continue?” “What will happen next?” and “Why are the voters so angry?”

Conservatism 1.0

The answer is fascinating. To get there, let’s start with the roots of the modern conservative movement. Initiated largely by William F. Buckley, Jr. and his colleagues in the 1950s and 1960s,[i] Conservatism 1.0 struggled, persisted, gained support slowly, and then rose to victory with the election and presidency of Ronald Reagan.

The Party of Reagan was based firmly on the view that “liberalism is bad.” In this environment, Reagan’s GOP found itself directly opposed to the Democratic Party of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his progressive successors.

The ensuing debate pitted conservatism against liberalism in a few direct, simple ways: limited government versus big government, Constitutional originalism versus judicial activism, American exceptionalism versus European style internationalism, and individualism versus collectivism.

Republicans saw conservatism as good precisely because it espoused limited government, strict adherence to the Constitution, American leadership in the world, and individual freedoms. They saw liberalism as bad because it promoted big government, an activist Court, American subordination to international organizations, and widespread collectivism through higher taxes and increased government programs in all facets of life.

This was the battle of Postwar America. And conservatives saw themselves as the Keepers of Freedom and Family Values in this monumental conflict—warriors for the American Dream and the American way of life.

After the financial downgrade of the Soviet Union during the Reagan years and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the battle lines were slowly redrawn. New superpowers emerged on the world stage, and existing alliances began to unravel. Naturally, during the 1990s the old battles were replaced with new ones, and in the 2000s world and national allegiances were weakened, redirected, and reconceived.

But the hearts of many 20th Century conservatives (and liberals, for that matter), raised and steeped in the old battles, didn’t change.

Conservatism 2.0

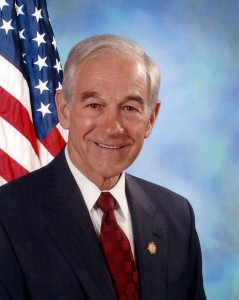

A new cultural movement sprouted in the different soil after 1989. In technology, this shift was exemplified by Steve Jobs, and eventually Elon Musk. In business, the iconic figureheads were Bill Gates and Warren Buffett. And on the political front, the pioneers of a new model were Ross Perot and Ralph Nader, and later Bernie Sanders and Ron Paul.

A new cultural movement sprouted in the different soil after 1989. In technology, this shift was exemplified by Steve Jobs, and eventually Elon Musk. In business, the iconic figureheads were Bill Gates and Warren Buffett. And on the political front, the pioneers of a new model were Ross Perot and Ralph Nader, and later Bernie Sanders and Ron Paul.

Congressman Paul’s contribution to the new brand of conservatism that arose is hard to overstate. For example:

- It replaced Reagan’s 11th Commandment (“Thou shalt not criticize other Republicans”) with a focus on principles of freedom rather than institutional political parties.

- It walked a fine (and frequently uneasy) line between party loyalty and going independent, finally resting on the idea that independence is more important than party—but sometimes it’s possible to get both.

- It called into question widespread U.S. military interventionism.

- It reemphasized the Constitution as a central, literal theme, rather than a mere national symbol.

- It put actual free enterprise above the rhetoric of free enterprise (rhetoric that most Republican presidents had ironically combined with bigger government).

- It appealed strongly to populism—“this is the people’s government, not vice versa.”

- It switched the viewpoint of conservatism from “liberalism is bad” to “government by elite power brokers and their bureaucratic agents is bad.”

Paul himself wasn’t able to convert this revolution into a White House victory, but the revolution occurred nonetheless. And the 7th point of this revolution is perhaps the most important. It animated the Tea Parties, the elections of 2010 and 2014, and it is still growing today.

It also explains the shock of the current Republican Establishment with the ousting of Eric Cantor, the support for Donald Trump, Ben Carson, and Carly Fiorina, and the popularity of Ted Cruz in comparison to Jeb Bush or Scott Walker.

Mitch McConnell, John Boehner, John McCain, Mitt Romney, Jeb Bush, and most of the Republican Establishment are operating as if the GOP is still Reagan’s party. But this is debatable. A large segment of the party is now more aligned with Conservatism 2.0.

Thus the passionate battle now underway for the future of the GOP. And with each passing election cycle, the popularity of Conservatism 2.0 is increasing.

What 2.0 Conservatives Want

To these new conservatives, the idea that “liberals are bad” is SO forty years ago. The real issue now is that “government by elites” is bad.[ii] “The elite class is bad. It is corrupt, and it’s hurting us all. It is hurting America.” In fact: “Corruption is bad. And elites are corrupt.” This viewpoint is growing.

And to members of the new conservatism, Republican elites are just as bad as liberal elites. Many consider them even worse, like modern wolves in sheep’s clothing, claiming conservatism, and gaining support for their candidates and policies by invoking conservatism, while refusing to passionately or effectively fight for it.

It is important to clarify that the Ron Paul revolution didn’t win all 7 of its main themes. The new 2.0 conservatives never warmed up to items 3 and 4, for instance:

3-less U.S. military interventionism in the world

4-more emphasis on the literal words of the Constitution

But, on the other hand, they bought the following principles hook, line and sinker:

1-focus on principles of freedom rather than institutional parties

6-populism: forget “electability” and support the candidate we think will really bring about the changes we want

7-government by elites is corrupt and bad

This tectonic shift put Carson, Trump, Fiorina and Cruz at center stage.

A Question

It remains to be seen if a 2.0 candidate can become the nominee anytime soon. And even more significant is the question of whether a 2.0 president will actually apply item 5 from the list:

5-actual free enterprise is the goal, not just the rhetoric of free enterprise

Such an approach would lead to balanced budgets, reversal of the U.S. national debt, and a high-growth economy spurred by a massive rollback of anti-small business regulation. Right now many 2.0 voters are split. They’re asking themselves if Trump or Fiorina would actually lead a serious downsizing of government—or instead just expand government like past 1.0 conservative presidents.

As for Carson and Cruz, they seem clearly committed to this approach, but 2.0 conservatives wonder if they have the capacity or authentic will to actually pull it off.

If the 2.0 crowd ever coalesces around one candidate, he or she is going to be very hard to beat—in the primaries, and even in the general. A motivated 2.0 nation will be very persuasive among independents, women, and young voters. And 2.0 is very strong in the swing states. But 2.0 conservatives won’t “go for it” if they are at all uneasy about the candidate’s direction or ability. They are, in a sense, playing the long game, and won’t blow their one-shot-at-the-big-house political capital on an also-ran.

The Election

A long primary and general election fight is still ahead, and this war between conservatism 1.0 and 2.0 won’t be easily resolved. It has already turned nasty, and it will probably get a lot worse.

But if 1.0 wins, if Jeb or another Establishment candidate is the eventual nominee, this fight will rage on. Conservatism 2.0 is young, passionate, and has the benefit of a large and growing base. It may or may not get its way in 2016, but all indications are that it will eventually win the war.

When it does, expect the president it propels into the White House to alter American history as significantly and lastingly as the 1.0 movement did with Ronald Reagan.

(Read more discussion on these themes in FreedomShift, by Oliver DeMille)

[i] With significant support by additional voices including Leo Strauss, Milton Friedman, Leonard Read, Friedrich Hayek, Russell Kirk, Richard Weaver, Ludwig von Mises, Ayn Rand, and Margaret Thatcher, among others.

[ii] In comparison, Liberalism 2.0, supported early on by Hobson and Mencken and Keynes, among others, and perhaps most embodied in current events by President Obama (and espoused by Bernie Sanders), frequently operates on the idea that “America is bad.” European social democracy is promoted as the alternative, the ideal, and the goal.

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History &Independents &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Politics &Statesmanship

The Real Crisis of the 2016 Election by Oliver DeMille

September 10th, 2015 // 6:30 am @ Oliver DeMille

“U.S. median income is $42,000 per year, while the European median income is $27,000. That’s close to the average difference in annual income between U.S. high school grads ($28,000) and college graduates ($45,000). And the current elite class wants America to become more like Europe. This explains much of what Washington is doing these days.”

What Is Coming

There is a serious crisis coming. Most people just hope it won’t come. Their subconscious minds tell them: “If we hope hard enough, and avoid thinking about it, maybe it won’t happen.”

There is a serious crisis coming. Most people just hope it won’t come. Their subconscious minds tell them: “If we hope hard enough, and avoid thinking about it, maybe it won’t happen.”

Sadly, it isn’t quite that simple. The crisis is coming.

What’s the Crisis? Imagine this: It’s the summer of 2017, and we have another career politician in the White House. On the day of the 2016 election, or even earlier, we learned that none of the anti-Establishment candidates were going to win. Instead, the media informed us that the American electorate was putting another regular politician into office.

And since inauguration day, that president has followed a path similar to earlier presidents, from Bush I and Clinton, to Bush II and Obama: the national debt is still skyrocketing, our foreign policy is a disaster, the government is growing, increased regulations attack our prosperity every month, and the Supreme Court is legislating additional policies that hurt the nation.

On top of all this, the mandates of Obamacare are really kicking in now, increasing many small business costs by 30% or more annually—and as a result, those businesses that survive are laying off large numbers of employees. Your family health insurance premiums are up many thousands of dollars a year. The economy is still struggling, with less than a 2% growth rate, and good-paying jobs are increasingly scarce. At least one or two of your close friends or family members have lost their jobs.

In other words, it’s clear that the 2016 election has changed almost nothing. Terrorist attacks are increasing in both Europe and a few targeted attacks in the United States—as Iran uses its new $100 billion dollars to fund such violence. ISIS is still spreading, and China continues to increase its naval presence around the Pacific Rim. Moreover, Putin is becoming increasingly aggressive, not just in Eastern Europe but also in Syria, the North Pole, and the Pacific.

If the new president is a Democrat, there is a strong push to increase taxes and federalize even more state-level programs. If, contrast, if the president is a Republican… well, exactly the same thing is happening.

If we vote for the same kind of candidate we’ve voted for since 1988 (a career politician), we’re going to get the same thing we’ve experienced since…you know…1988. Meaning that career politicians are going to give us the same thing that career politicians have always given us:

Increased government. Very little positive change. A continual slide toward bigger government, higher debts, and decreased individual prosperity and freedoms.

Coming Paths

This is the crisis ahead: More of the same. Except that it’s continually a bit worse, year after year, election cycle after election cycle.

“The definition of insanity,” you remind yourself, “is to keep doing the same thing while expecting different results.” In business, the prime directive is that to actually change an organization, you have to significantly change the leadership. If career politicians keep running the White House, little is going to change. This is true.

It’s frustrating. We don’t want to believe it, because we hope things will be different this time. But each election proves that it’s the reality. Career politicians do what career politicians do. Over and over.

Specifically: whatever career politicians say as candidates, once they’re elected they do what they’ve done before. Count on it. The following presidential candidates are not going to bring much change to Washington:

- Joe Biden

- Hillary Clinton

- Jeb Bush

- Chris Christie (to his credit, Christie is openly promising to do what career politicians do: just more of the status quo)

- Marco Rubio

- Scott Walker

- John Kasich (actually, at least Kasich has balanced two major budgets—the federal budget during the 1990s, and Ohio’s budget while serving as governor; thus, he’ll likely do this again—even if he doesn’t do much else, this is a pretty good thing)

But does anyone actually believe that if Jeb Bush is elected president we’ll reverse the national debt, repeal Obamacare, or seriously send education decisions and funding back to the states, where it belongs? No way.

The above candidates are part of the system; and reaching the pinnacle of the system they’ve spent their lives supporting won’t incentivize them to drastically change things. Whatever your political views, it’s clear that those who’ve made their lives in the system aren’t likely to alter it in any significant way. Period.

The following are a lot more likely to really change things:

- Bernie Sanders

- Carly Fiorina

- Rand Paul

- Donald Trump

- Ted Cruz

- Ben Carson

Say what you want about them, but they aren’t part of the typical Washington Establishment.

If elected, would one of them actually change things?

Maybe. Maybe not. But there is at least a chance.

In contrast, with the first list above, there’s no reasonable, rational expectation of real change.

Part II: What Will the Crisis Look and Feel Like for Americans?

Beyond the question of whether or not real change will come after the 2016 election, a deeper question is this: “If it doesn’t come, what will happen?”

In other words, “Where is our current national trajectory taking us?” First of all, if real change does come, it could take a number of different directions. That’s what change does. Genuine change is almost impossible to predict, because a significant change causes so many additional, cascading, changes.

If anyone on the first list above becomes our next president, I believe we have less than a 1% chance of changing course in a serious way that really shifts our national direction. Even if someone on the second list is elected, I’m convinced we’ll have less than a 40% chance of such a course correction (and 0% if it’s Bernie Sanders).

And let’s be clear: a course correction is desperately needed. If it doesn’t come, where are we headed?

Answer: In the early 1960s, many in the Euro-American elite class adopted the idea that the U.S. was beginning to outpace the nations of Western Europe—economically, technologically, and militarily. Moreover, they calculated that such a divide would be bad for business (specifically the business of the elites, which includes both the economic endeavors of the 1% and also their political influence).

To combat this growing divide, the elites began using their institutional, fiscal, and monetary influence to make the United States more like Europe. They began in earnest by dropping the gold standard in 1971, and providing an influx of elite money into higher education donations and endowments, and simultaneously with increased investment in and ownership of major media outlets.

Influenced by these funds and those who provided them, education began spreading the idea that America should be more like Europe, and the graduates of these programs increasingly dominated the campus scene through the seventies and eighties. By 1987, Allan Bloom decried what amounted to the Europeanized politicization of higher education in his bestselling book The Closing of the American Mind.

Choosing a Dream

Media increasingly reinforced this same message—“America should be more like Europe”—in stories and reports, from the major national newspapers to the Big 3 television networks. Nearly all cable channels and Establishment-supported Internet news outlets followed suit.

Among Establishment policy makers, Samuel Huntington’s writings on “Civilizations” and Francis Fukayama’s “End of History” essays pointed U.S. financial-, domestic-, and foreign-policy institutions (and bureaucracies) in the same direction.

Where does this leave us today? The “American Dream” includes the ideal that each household should achieve home ownership, financial independence (at least by the time of retirement), cars, savings, education for the kids, and a better lifestyle for each additional generation. In contrast, a middle class family in Europe typically lives in an apartment, has fewer children than American families, owns (on average) less than one car, and expects decreasing financial opportunities for coming generations.

To put this in financial terms, the U.S. median income is $42,000 per year, while the Western European median annual income is $27,000.

While it may not appear so at first, these numbers are drastically different—especially if you are applying for a home or vehicle loan, trying to start a business, deciding how many children to have, or funding a child’s college education. Indeed, an American family of three making the European median income of $27,000 a year typically lives in an apartment and has approximately $4,050 a year or less in disposable income. The U.S. median income of $42,000 upgrades the family to a home and $12,180 in annual disposable income.

That’s roughly the same as the average difference in annual median income between U.S. high school grads ($28,000) and college graduates ($45,000). That’s right: the direction of U.S. median income is headed toward less than the average wages of high school grads.

This comparison is not overstated. This is where we’re headed. Of course, the affluent classes won’t suffer this same fate, but a lot more Americans will become part of the struggling class. Just like in Europe.

Who we vote for matters.

If we want real change, we need to vote for something different.

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Business &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Education &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History &Independents &Leadership &Liberty &Politics

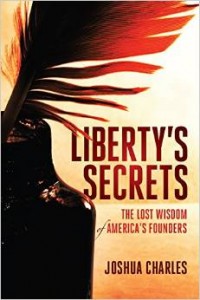

A New Great Book in the Battle for Freedom! Review by Oliver DeMille

August 19th, 2015 // 2:36 pm @ Oliver DeMille

Steps to Freedom

I read another great book today, and it rekindled my sense of hope for the future. If you care about freedom, you’ve got to read it! This new classic is Liberty’s Secrets by Joshua Charles, and it is…

I read another great book today, and it rekindled my sense of hope for the future. If you care about freedom, you’ve got to read it! This new classic is Liberty’s Secrets by Joshua Charles, and it is…

But I’m getting ahead of myself. There’s a story here, an important one. And I need to tell it in order to do justice to this book. In a world of brief sound bites and too frequently shallow media and educational conversations, a great book is easily overlooked. Such greats all too often go unnoticed because we live in an era of constant—aggressive—distraction. So to introduce a genuinely great book, we need to get this right. Here goes…

I. The Great Books

I was a young boy when first it happened, old enough to ride my bicycle to the library on hot summer afternoons and find interesting books to read, but young enough that high school sports and summer trainings weren’t yet part of my daily routine. One day under the memorable breeze of the town library’s large swamp cooler I came across a long shelf of books that boldly called themselves “The Great Books”. I stopped and stared. I re-read the title, then pondered.

“These can’t be the only great books,” I reasoned to myself. “There must be others.” Intrigued, I pulled out a volume and perused the title page, then skimmed through several chapters at the beginning of the book. I was impressed by the small print, the columns and footnotes, and the sheer quantity of big, unfamiliar words. They were downright intimidating.

I marveled a bit, rubbing my fingers along the cloth-covered bindings. I knew I would read these books some day. I just knew it.

I remember nothing specific about which volumes I investigated that day, but I skimmed many of them, reading a sentence here and another there. The afternoon passed, and I eventually returned the last volume I’d removed to its place on the shelf and went to the front counter to check out the L’Amour novel I’d selected for the week’s reading.

We lived in the desert, and it was a very hot summer, so during the exertions of my bike ride home I forget about the “Great Books”. But each time I returned to the library, I noticed them again. It seemed like none of them were ever checked out, and I could well believe it. They were truly daunting, with their gold foil lettering, fancy author names, and massive domination of shelf space.

II. Fast Forward

Today I just finished reading a truly great book on freedom, and I smiled widely as I completed the last few lines and closed the book. I removed the dust jacket and ran my fingers over the sleek black hardcover with the red foil print. “I was right, that day,” I thought to myself.

Then I realized I had been right on both counts. I would, in fact, come to read the whole set someday. I couldn’t have known at the time that I would re-read The Great Books many times, teach them extensively in multiple university, high school, and graduate level courses, and spend many hours discussing their content with colleagues, business executives, students, professionals, family members, and friends. The Great Books volumes have become dear friends over the years, and I have returned to them often for heated debates with their authors or to rehash unfinished questions in the “Great Conversation”.

But I was right about the other thing as well: there are great books beyond those in Britannica’s 54 volume set. And when I encounter an additional great book, I always feel a sense of excitement. Great books are great because they are important. That’s the major criterion. They have to be truly significant, to add meaning to our world—to innovate something that wasn’t there before the book brought it to life.

III. What Makes “Great”?

Over the decades I’ve experienced several great books beyond those from the “official list,” and they always leave an impression. Like The Closing of the American Mind by Allan Bloom, The Third Wave by Alvin Toffler, or The Five Thousand Year Leap by W. Cleon Skousen. Such books, like those by Bastiat or Austen, simply must be added to list. Along with Solzhenitsyn’s works.

In recent years I’ve come across several additional great books, like Andy Andrew’s The Final Summit, Chris Brady’s Rascal, Stephen Palmer’s Uncommon Sense, Orrin Woodward’s Resolved, Judith Glaser’s Conversational Intelligence, or Henry Kissinger’s On China. I also studied an old great book I hadn’t ever read before, The Early History of Rome, by Livy, and found greatness in its pages as well. When you read a book that is truly great, it’s a moving experience.

Such books come along rarely, so when they do it is important to pay attention. But what makes a book genuinely great? After all, greatness is a very high standard. It can’t just be good. As Jim Collins reminded us, good is too often the enemy of great.

Nor can it simply be well written. It can’t merely be accurate, detailed, beautiful, or interesting. More is necessary. It can be one, a few, or all of these things, but to be truly great, it must be also be transformational. It must change you, as you read.

IV. A New Great Book!

When I started reading Joshua Charles’ book a few days ago, I didn’t know I was in for such a treat. I had already enjoyed his earlier bestselling work, so I was ready to learn. I got my pen and highlighter out, and opened the cover. But as I read I realized that this book is truly very important. Needed. And profound.

Then, as I kept reading, I noticed that I was feeling something. A change. A different perspective. A re-direction. I was experiencing…the feelings that always accompany greatness.

Charles notes in several places that as a member of the Millennial generation he felt compelled to share this book with the world. Why? Because, in his words: “I wrote this book for one reason, and one reason only: to reintroduce my fellow countrymen to the Founders of our country and the vision of free society they articulated, defended, and constructed, in their own words.”

As a member of Generation X, I was thrilled to see a Millennial take this so seriously—and accomplish it so effectively. Even more importantly, as I read I noticed something very important, subtle but profound. Charles doesn’t make the mistake of so many modern authors who write to the experts and professionals in a field. His scholarship is excellent, and he goes a step further. He has a more important audience than mere political or media professionals. He writes to the people, the citizens, the voters, the butchers and bakers and candlestick makers—the hard-working people who make this nation go, including the artists, scientists, teachers, executives and leaders.

In so doing, he is a natural Jeffersonian, speaking the important principles of freedom, culture, economics, and leadership to a nation of people—not merely to politicos or aristos, but to everyman. To underscore this (and I doubt it was a conscious decision on his part, but rather his core viewpoint), his word choice refers not to “the American voter” but rather to “we the people.” He considers himself not merely the expert, but one of us, one of the people.

I could have hugged him for this, had he been here in person. We have far too few freedom writers today who see themselves truly as part of the citizenry. When they do come along, albeit rarely, I feel a sense of kinship and I know that their hearts are in the right place. Jefferson would be proud. For example, Charles wrote:

“We no longer know where we came from, the grand story we fit into, and the great men and women who inspired the noble vision which birthed the United States of America, the first nation in history to be founded upon the reasoned consent of a people intent on governing themselves….

“Additionally, few of us are well-read enough (a problem our educational system seems blithely unconcerned with) to discuss the lessons of the human experience (often simply called ‘history’)…”

Freedom, the classics, voracious reading, leadership, and the future—all rolled into one. “This is my kind of author,” I realized, once again. “These are the themes I emphasize when I write.” So did Jefferson. And Skousen, and Woodward. No wonder I love this book.

The Current Path

More than profound, Charles’ book is also wise. Belying his Millennial generation youth, he speaks like an orator or sage from Plutarch when he warns:

“Liberty is difficult work. It is fraught with risks, with dangers, with tempests and storms. It is a boisterous endeavor, an effort for the brave and the enterprising…”

These latter words have stayed with me since I read them several days ago. I keep remembering them. Boisterous. Brave. Enterprising.

These are the traits of a free people. In classical Greece, among the ancient Israelites, in the Swiss vales, the Saracen camps, the Anglo-Saxon villages, and the candlelight reading benches of the American founders—wherever freedom flourished. Yet today we train up a nation of youth to be the opposite. To fit in (not boisterous). To avoid risk (not brave). To focus on job security above all else (not enterprising).

If this trajectory continues, our freedoms will continue to decline.

Where and When

Speaking of freedom, Charles calls us to immediate action with his characteristic humility, depth, and conviction: “We either pass it [liberty] on to our posterity as it was passed down to us, or it dies here and now.”

Here and now? Really?

Is it that immediate? Is it truly this urgent? Is it really up to us?

The answer is clear: Yes.

Yet, it is.

“He gets it.” I smile and take a deep breath. Then I whisper to myself: “Another great book!”

I hold the book sideways and look at the many pages where I have turned down the corners. Dozens of them. Just for fun, I open one of them and read:

“…we have every reason to be doubtful of, skeptical about, and disdainful toward the notion that Caesar [government] can solve all our problems.”

I nod. When freedom is under attack, leaders rise up from among the people. This book is part of that battle.

“The Great Books indeed.” I grin as I say the words.

I turn to another page with a dog-eared corner and read Charles’ words:

“‘Society is endangered not by the great corruption of the few, but by the laxity of all,’ Tocqueville had noted, and on this he was in complete agreement with the Founders.”

And now, I note, with at least one Millennial.

I feel a sense of building hope for the future. “The Millennials are beginning to lead,” I say with reverence.

“This is big. And if this book is any indication of what’s to come…

“It’s about time,” I say aloud.

Then, slowly, “Everyone needs to read this book.”

*Liberty’s Secret by Joshua Charles is available on Amazon

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Book Reviews &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Education &Featured &Generations &Government &History &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Politics &Statesmanship

A Proposal on Reforming the Supreme Court

July 28th, 2015 // 8:12 am @ Oliver DeMille

by Oliver DeMille

I don’t mean it. I’m going to propose it, but I don’t really want it. Or think it’s a good idea. This proposal is meant to be ironic. But it still needs to be said, because there is far too much truth to it.

Supreme Parliament of the United States

In the wake of recent Supreme Court decisions, it’s clear that the Court doesn’t just try cases. It now writes law. It isn’t only a Supreme Court, it’s the de facto Supreme Parliament of the United States as well.

In the wake of recent Supreme Court decisions, it’s clear that the Court doesn’t just try cases. It now writes law. It isn’t only a Supreme Court, it’s the de facto Supreme Parliament of the United States as well.

The Court uses some decisions to simply rewrite the laws of the nation, including the laws of the states. It’s been doing that for some time,[i] of course, but now it’s taking this approach to a whole new level. It has decided that the 9th and 10th Amendments are outdated, and it just ignores them.

For example, the Court labels Obamacare a “tax”, even though the Congress and President who proposed and passed it never called it that, and even though it skirts many state laws. The Court just makes up its own way.

Forget the actual case at hand; the Court is convinced that it has the power to create whatever it chooses out of thin air. Whatever the Court says, goes. Call it a “tax”. And call marriage a Constitutional right, even though the word “marriage” and the concept of marriage are never even mentioned in the Constitution or any of the Founder’s commentaries on the federal Constitution.

The Framers specifically left any and all decisions about marriage to the states. The Court has amended the Constitution without even using an official amendment.[ii] Many times. Just because it wants to.[iii] I’m not saying the Court got any of these recent decisions wrong, or right. That’s not my point. In fact, my point is much more important than any of these cases. I’m saying the Court has no authority in the Constitution to make many of its decisions.[iv]

It gave itself the power to do these things.[v] It just took the power. Such power didn’t come from the people or the Constitution.[vi] Such power isn’t legitimate authority. It is, to use the precise, technical word that the Founding generation used for this exact behavior: “tyranny”.

Whether you love the current Court’s decisions, hate them, or fall somewhere in the middle, the bigger picture is beyond the cases. The Court is now boldly and fully engaged in Judicial Tyranny.[vii]

The new rules of the Court: Just do whatever you want. You’re the Court, after all. Oh, and that pesky reality that the Constitution doesn’t give the Court the authority do more than half of what it now does? No problem. Since you’re the Court, just announce that the Constitution does, in fact, give you such authority. In fact, decree that the Court has the Constitutional authority to do whatever you decide to do.

Jefferson warned that this very thing was the biggest danger to the Constitution and to American freedoms. And his prediction has come true. The Legislative Court has become one of the greatest dangers to our freedoms. Five lawyers literally have the power to do whatever they want.

The Proposed Change!

So here’s the proposal. I heard it on a radio show, and it made me laugh. Then it made think. Then it made me mad. Check this out:

Since the Supreme Court now makes up any law it wants just by writing it up in a majority opinion, without bothering about what the House or Senate does, let’s balance the budget by just disbanding Congress. Why pay Representatives and Senators and their staff when the Court is just going to write up laws on its own anyway?

That’s the proposal. Let’s just get rid of Congress and let the Court keep doing its thing.

Again, I don’t really mean it. But at this rate, the Court is on pace to do this anyway. And in the meantime, it’s already behaving as the Supreme Court and the Supreme Parliament all in one.

One More Thing

By the way, the real solution is for Congress to pass legislation ending the use of precedent in the courts and limiting every Supreme Court decision to the scope of that one case. This will send many in the current generation of lawyers into a tizzy, but it’s the right thing to do. Assuming that we want to remain free. Such a change will immediately return the Court to its Article III powers.

Or, barring this solution, if we’re going to keep with the bad tradition of common law precedent,[viii] amend the Constitution so that 2/3 of the state Supreme Courts can overturn any decision of the Supreme Court. (More on Common Law in footnote “viii”.)

If we don’t do one of these, we literally might as well adopt the proposal above—because the Court is now operating as both the Judicial Branch and a Higher Legislative Branch.

NOTES

[i] See, for example: Martin v. Hunter Lessee; Cohen v. Commonwealth of Virginia; McCullough v. Maryland; Gibbons v. Ogden; Missouri v. Holland; New York ex rel. Cohn v. Graves; U.S. v. Butler; U.S. v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp.; Wood v. Cloyd W. Miller; among others. See also: Bruno Leoni, Freedom and the Law, 3-25, 133-171.

[ii] Compare Article VI of the United States Constitution to Article III.

[iii] Some scholars and jurists will balk at this, arguing instead that the court “finds” or “discovers” the Constitutional meaning in the law. But while the Court may employ technical and/or logical language to support its decisions, it still utilizes its will. It may claim that its decisions are “findings,” and at times they are, but they are still always decisions. (If they were truly “findings,” matters of law without personal choice, all cases would be decided by 9-0 votes. Will is part of each decision.) Moreover, despite what is taught in some law school courses, the Framers clearly understood votes of the Justices to be acts of will, not mechanized requirements demanded by the laws.

[iv] Read Article III word for word. No such powers are granted.

[v] Review the cases listed in footnote “i” above. See also: John E. Nowak, Ronald D. Rotunda (Thompson-West), Constitutional Law, Seventh Edition, pp. 1-16, 138-156, 397-398.

[vi] Article III.

[vii] See how Raoul Berger warned of this a generation ago: Raoul Berger, Government by Judiciary.

[viii] Many in the legal profession argue that the Framers preferred Common Law to the other alternatives. Certainly there are a number of quotes from prominent founding leaders that on face value seem to support this view. In reality, most of the Framers preferred Common Law to Romano-Germanic Codifications. This was the major legal debate of the era, in Europe at least. Thus the Justinian model was soon to be followed by the Napoleonic Code. So when the Framers sided with Common Law over the Romano-Germanic model it was taken as a blanket endorsement of the Common Law. However, some of the top Founding Fathers, including both Jefferson and Madison, preferred a third model, the Anglo-Saxon code and system, over Common Law. For excellent background on these competing systems, see: Rene David and John E. C. Brierley, Major Legal Systems in the World Today; John William Burgess, The Reconciliation of Government with Liberty; Theodore F.T. Plucknett, A Concise History of the Common Law. In short, common law builds on precedent; the Constitution the Framers wrote didn’t require the use of precedent by the Judiciary. In the Framer’s model, the Court was “supreme” in deciding any one case. Period. This keeps the Court separated in the judicial realm. It is an independent judiciary, unlike in Britain, because it has sole authority to provide the final determination in any one case. But separation of powers gives it no authority to use dicta or precedent to influence later cases. Any allowance of precedent creates the need to explain a decision, and moves into the realm of legislation. Common Law was not the intent of the Framers. Once the Constitution was ratified, however, the attorneys of the era, trained in the Common Law, simply kept practicing their system without change. The Anglo Saxon code and model was quickly lost, to the detriment of American freedom. Most attorneys are unaware of this. Even a lower percentage of non-attorney citizens understand this. We lose our freedoms in many cases simply because we don’t know better.

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Current Events &Education &Generations &Government &History &Leadership &Liberty &Politics &Statesmanship

An Obama, Adams, and Jefferson Debate

June 1st, 2015 // 6:15 pm @ Oliver DeMille

(Should Presidents be Treated Like Royalty?)

News and Fans

A strange thing happened recently. President Obama visited my state, just a quick flight and a few meetings. But to watch the state news reports, you would think the most important celebrity in all of history was visiting. The media simply fawned over the president. The news channels broke into all the nightly television programs and gave special reports. Not on some major announcement, but on…wait for it…the President arriving at his hotel.

A strange thing happened recently. President Obama visited my state, just a quick flight and a few meetings. But to watch the state news reports, you would think the most important celebrity in all of history was visiting. The media simply fawned over the president. The news channels broke into all the nightly television programs and gave special reports. Not on some major announcement, but on…wait for it…the President arriving at his hotel.

Reporters were on the scene. Anchors cut back and forth between the reporters and expert guests opining on how long the President’s day flight been and how much longer before he would arrive at the hotel. This went on and on. No news. No policies. No proposals. No events. No actual happenings.

Just a president and his entourage arriving in a plane, being driven to the hotel, and staying overnight. The reporters and other news professionals—on multiple channels—were positively giddy.

I shook my head in amazement. The American founders would have been…well, upset. At least Jefferson would. Adams? That’s a different story altogether. In fact, it got me thinking.

John Adams, the second president of the United States, made a serious mistake during his term in office. He had served for a long time as ambassador to the English crown, and he picked up some bad habits in London. He witnessed the way members of Parliament treated the top ministers in the British Cabinet, and how the ministers themselves fawned over the King.

He had, likewise, watched how the regular people in England bowed and scraped to the aristocracy. Almost everyone in Britain saw every other person as either a superior, an inferior, or, occasionally, an equal. This class system dominated the culture.

And, as an ambassador of the American colonies, Adams had been pretty low on the pecking order in London. He had seen how this aristocratic structure gave increased clout to the King, to Cabinet members, and to the aristocrats. So when he became president, he wanted the U.S. Presidency to have this same sense of authority, power, and awe.

In fairness, reading between the lines, I think president Adams’ heart was in the right place: He thought this would help the new nation gain credibility in the sight of other nations. He wanted the president to be treated like royalty.

But Adams forgot something very important.

Aristos and Servants

Americans weren’t raised in such a class system. They found such bowing-and-scraping to the aristos both offensive and deeply disturbing. For them, this was one of the medieval vestiges of the old world that America (and Americans) had gratefully left behind. The principle behind this was simple: if we treat leaders like aristos and kings, they’ll start acting like aristos and kings, and our freedoms will be in grave danger.

Moreover, Americans felt that such “prostration before their betters” was especially inappropriate where government officials were concerned. “Government leaders work for us,” was the typical American view. And if the citizens start acting like their leaders are aristocrats and royalty, they’ll stop thinking and acting like fiercely independent free citizens.

Moreover, Americans felt that such “prostration before their betters” was especially inappropriate where government officials were concerned. “Government leaders work for us,” was the typical American view. And if the citizens start acting like their leaders are aristocrats and royalty, they’ll stop thinking and acting like fiercely independent free citizens.

But still Adams wanted the people to treat the president like royalty. Jefferson was appalled at Adams’ words and behavior in this regard, and his criticisms of President Adams’ on this matter fueled a rift between these two men that lasted almost two decades. At times, the biting rivalry and harsh words bordered on hatred—if not of each other, certainly of the other’s behavior.

Jefferson believed in a democratic culture, where each person would be judged by his choices and character—not by class background. Even more importantly, he believed that, in fact, government officials do work for the people—and the higher the office, the more they are servants of the people.

As president himself, Jefferson went out of his way to avoid and reject any “airs” or special perks of office. He saw himself as simply a man, one of the citizens, who had the responsibility to serve all the other citizens. He wasn’t superior to them—he was the least of them, their servant, their humble servant.

After 8 years as president, Jefferson had established this as the way each president should be viewed: a regular citizen, serving as president while elected, but not treated as inherently royal, superior, or in any way better than anyone else. No perks, no special treatment. Yes, security for the Commander in Chief obviously needed to be different than for the average person. But other than that, no aristocratic fawning was appropriate.

Madison followed the same model, and after him Monroe. So did John Quincy Adams and other presidents through the eras of Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt, and FDR. Truman angrily rejected any attempts to put him on an aristocratic pedestal.

Eisenhower rebuffed aristocratic perks both as a general and later as president, and Kennedy did the same in many ways—leaving his expensive upper-class clothes at home and dressing more like the people he worked with each day while in Washington. Reagan openly pushed against any aristocratic airs; as a movie star he was accustomed to celebrity, but clearly avoided it as president. He wanted to be a man of the people, a servant.

Generational Visions

And even while Adams tried to promote a higher level of fawning over the president, at least the media of his era had the good sense to criticize him for it. To take him to task. To note that such is not the American way.

But something changed, somewhere along the way. Was it because Kennedy was considered American “royalty” even before the presidency, or because Reagan was already a Hollywood celebrity before he occupied the White House? Or did the change come during the Clinton era, or the Bush years? (Ironic that such fawning of the Chief Executive came after Nixon.)

Or was it the way Hollywood portrayed presidents—with actors like Michael Douglas or Martin Sheen glibly spouting a sense of arrogant power and aristocratic entitlement? Did entertainment capture our national imagination?

When did we start seeing the world as classes of royals, aristos, and “regular” people? When did “celebrity” become an accepted reason for special treatment in America?

Should we respect the offices held by our political leaders? Absolutely. Should we honor those who serve? Absolutely. Too often the level of civic discourse today is coarse and angry. More respect is needed. And, just as importantly, less aristocratic fawning is needed.

I once wrote about experiencing this trend firsthand while hosting a visiting dignitary many years ago. After an evening event, we went to a restaurant. The dignitary and I naturally walked to the back of the line, but one of the other hosts hurried to the front of the line and arranged for a “VIP table.” As we walked past the rest of the line, people vocally grumbled. We heard words like: “Hey, don’t cut in line,” and “You can wait your turn, just like the rest of us.”

When the other host responded by telling the people in line the dignitary’s title and name, the frustration grew louder. “We’re Americans too,” one man said. “We don’t worship titles in this country. Wait your turn.” A number of similar words were exchanged. The dignitary demanded that we go back to the end of the line just like everyone else.

Fast forward over two decades later. A similar scene. I walked with a dignitary to the back of a large restaurant line, and someone in our group arranged for us to go straight to our table. As we passed the line, people asked, “Who’s cutting in line?”

But these voices weren’t angry. They were just curious. “It’s a celebrity,” someone said. “Oh, okay,” was the general consensus. “Of course. Let him ahead, then.” Apart from trying to see if they recognized the person, everyone in the line seemed totally content to let a celebrity pass.

The earlier line had been made up mostly of people from the Greatest Generation and the Boomers, while the second line consisted mainly of Gen X and Millennials. The U.S. clearly changed during the two decades between these experiences. But is the change a good one?

It’s an important question: Can we maintain a democratically free society when the broad culture sees people as “superiors,” and “inferiors”? When we as Americans have come to see celebrities as naturally deserving special perks, and government officials as people to be submitted to? Won’t that change how we vote?

Indeed, it already has.

Focus and Fawning

Would John Adams like the way Americans now treat their presidents and other celebrities? What would the British aristos of the American Founding era think of Americans today? Are we just as “domesticated” as the London populace of their time? We don’t exactly “bow” yet, but have we become a nation that “bows and scrapes” before people we see as “our betters?”

And if this applies to “power celebrities,” meaning government leaders, what does that say about the American people as wise stewards and overseers of freedom? Politeness is good, no doubt. But which is classier:

- A people who move aside for aristos, craning their necks to catch a glimpse of celebrity and snap a photo on their phones, or,

- A people who think everyone is an important leader because we are all citizens of a great, free nation?

Whatever Adams would think of the way many Americans now turn giddy in the presence of political leaders, Jefferson, Washington, Franklin and Madison would not like it. Jefferson would certainly call foul. This is not the way to maintain a true democratic republic.

Whatever Adams would think of the way many Americans now turn giddy in the presence of political leaders, Jefferson, Washington, Franklin and Madison would not like it. Jefferson would certainly call foul. This is not the way to maintain a true democratic republic.

Treat everyone like aristos, or no one. Period. That’s the only way to be equal and fair.

Don’t treat some like aristos and others like commoners. Because if we do, freedom will quickly decline. (It will decline more for the commoners than the aristos, by the way.) Even Adams hated such obsequiousness when he witnessed it in Europe.

Clearly, as mentioned, the security of top leaders is very important. So is the security of everyone else, but it is true that top officials and celebrities often face more frequent threats. Also, more respect in our civil discourse is needed. But the servile toadying to political celebrity by many in our current populace and even media is a disturbing trend.

Again, we should certainly be respectful of important office. But sycophancy isn’t the American way—as Adams learned when the “commoners” refused to give him a second term. In fact, they instead entrusted the presidency of their nation to the leading voice of democracy and equal treatment for all citizens: Thomas Jefferson.

We should be so wise. Give us a president who stands what matters—boldly, openly, and effectively—while simultaneously rejecting the perks and “airs” of aristocracy, or worse, an Americanized royalty.

Give us a president who vocally reminds us that he or she is just one of the citizens. And who openly remembers and operates on the principle that we, the people, are the real leaders of the nation. It’s time for the media servility and simultaneously smug superiority of the White House to be replaced with what our nation actually needs—quality, grown up, leadership by someone who truly understands what makes freedom tick. The people.

As for the media, focus more on policy and principles, less on ratings and the “royals who lead us.” And none at all on what hotel somebody stays in. There are people with real needs in this country, and current policies are hurting millions of American citizens. Let’s fix them. Starting with spending our media airtime on what really matters.

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Featured &Generations &Government &History &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Politics &Statesmanship