Are We Entering an Era of One-Term Presidents?

July 22nd, 2016 // 2:49 am @ Oliver DeMille

Loyalties and Addictions

Many nations, and the global market as a whole, are moving from the Loyal Economy to an On-Demand Economy. (See Klaus Schwab, The Fourth Industrial Revolution, 2016, 72) This is just what it sounds like. Our societal focus is increasingly on what we want–not what we need, should want, or have already agreed to.

Many nations, and the global market as a whole, are moving from the Loyal Economy to an On-Demand Economy. (See Klaus Schwab, The Fourth Industrial Revolution, 2016, 72) This is just what it sounds like. Our societal focus is increasingly on what we want–not what we need, should want, or have already agreed to.

This shift is impacting work, business, management, leadership, professions, and even families, churches and communities in massive ways. It has already taken a significant toll on relationships in our modern society. Indeed, almost no part of human life has remained untouched by this momentous change.

Just think of all the ways damage can be caused by a shift away from loyalty, and changed to whatever someone wants instead, and you’ve got a pretty good indication of the problem. For example, as a society we have historically been known for being loyal customers—we either love or hate the Yankees, Cowboys, Lakers, etc., and many people have traditionally been very passionate about Ford or Chevy, West Coast or East Coast, City or Farm, New York Times or Wall Street Journal, Prada or Gucci, and so on.

As for Republican and Democrat, these attachments were often multi-generational, and as zealously maintained as one’s religion. For a number of people, these labels (GOP or Democrat) defined “who they really were as people” more than any other feature.

But in the Digital Age we’re losing many of these connections. A lot of people now switch allegiance to sports team based on how the best clubs are playing this season, and we change “favorite” recording artists or television shows almost as often as we change our socks nowadays. We press “Like” one day, and don’t press it the next. Just follow the Twittersphere—changing loyalties is new a national hobby. Or addiction.

The Line

With the endless options of the Internet constantly streaming in front of us, it’s not surprising that many customers—most customers in fact—consistently try out new options. Why not? Maybe the next one will be better.

The same is true of many companies. It used to be that good employees were given numbered pins each year or decade—to show how long they’d been at the company. The ideal was once to work your whole life with one organization, move up the ranks a little or a lot, and retire in the same company and town where you started your first job. The whole company threw a party, and you were presented with a gold watch, an engraved silver pen, or another memento of your long-term loyalty.

Today few companies exhibit such loyalty. Some, in fact, routinely purge upper-level management in order to replace more expensive employees with cheaper, younger models who are decades from earning a pension. The laws have made it much easier to carry your retirement savings with you from company to company, and a lot of people are constantly on the lookout for a better job elsewhere. There are popular apps dedicated to this habit.

Given today’s technology, and the nimbleness big organizations must somehow try to exhibit in order to remain relevant, such changes aren’t surprising. In fact, they may simply be the new way of things, the new normal. The old is always being replaced with the new. This week. In fact, in the news cycle Monday’s “crises” and “tragedies” often go unmentioned by Thursday.

Thus it isn’t shocking that our political leanings are going through an era of upheaval as well. During modern periods of economic and cultural stability, a majority of voters stick with the parties. Whether you like this approach or not, it’s usually the reality. Such majorities may be “silent” most of the time, but on election day they vote like the experts knew they would. They toe the party line.

Parties or Menus

We have seen this kind of stability erode a great deal since 2006. The iconic memory of 9/11, followed by the failure to find weapons of mass destruction in Iraq or win the wars in Iraq or Afghanistan easily and quickly, threw the electorate for a loop, and the Great Recession that followed moved us decisively away from political stability—at least for a while. China, Russia, the Middle East, North Korea, fluctuating prices, an economy that never seems to recover, and so many other things contribute to a growing sense of chaos, and of things getting worse.

Indeed, elections seem to get crazier and crazier. Predictions by the top experts, and the masses of talking heads, are now routinely wrong.

This isn’t driven by a cycle, however, meaning that we can’t chalk it all up to “a phase” the nation is going through before it reverts back to its traditional, normal behaviors. Cycles and trends do sometimes explain things that happen, but this time something more is going on. The rise of nearly-ubiquitious digital mobility is still in its infancy, and it is quickly restructuring politics (along with marriage, family, community, education, career, business, the economy, etc.).

Voters are less and less likely to be Loyalty Voters, emotionally attached to one party that stands for their culture, their beliefs, their family traditions. Indeed, in a world where more and more people are routinely questioning their birth culture and family traditions, they’re not likely to let loyalties based on these things get in the way of change.

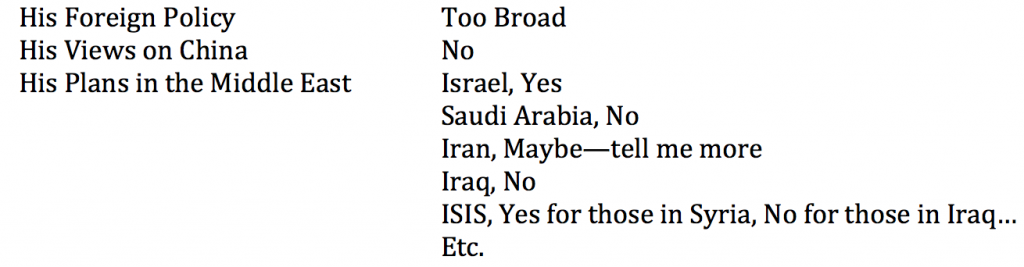

Specifically, we are entering a Pragmatic Era in politics, where people want on-demand government. They want a menu of options to choose from, not a political party and its bureaucracy. They don’t really want to choose between candidates. They want a little of what one candidate has, but without the rest of his ideas. They want some of what another candidate promotes, minus his personal views, or his stand on [fill in the blank…]. They like what they hear from one candidate on one day, but disagree with what she says the next.

Response Government

It’s not so much a targeted electorate where the candidates try to win over the biggest special interests—like it has been for the past two decades. What’s emerging now is, to repeat, a growing clamor for on-demand politics. Voters want to unbundle government. They want to be able to select “yes” items and “no” items from every candidate running for high office.

In other words, they want Washington to live in the Digital Age. They want to directly email—or, better still, text—presidential candidates and have an on-going dialogue with them, and then continue the dialogue after the president is elected.

“I liked your speech yesterday at Georgetown, except for the part on naval upgrading. What actually needs to happen is…”

Moreover, they want the President to answer their email.

“Thanks, Amy. I see your point. I’m meeting with the Joint Chiefs later today and I’m going to tell them your recommendation—and order them to do it. They really need it. Good thing you’re on our side and sent me that email.”

Today’s voters want the government to respond the way Amazon does. Immediately. In fact, they want to be able to sign up for the President’s Prime service—free answers within the hour, and nearly-immediate government implementation of whatever you tell the Oval Office to do.

“Get your policy implemented by Tuesday at 8 p.m., if you order it in the next 8 hours and 41 minutes. To get it by Monday at 8 p.m., pay an extra $3.99 and click here…”

As a result of this shift in voter expectations from their government (and the fact that government is still stuck in the 60s–or maybe the 70s–ways of doing things), hardly anyone is truly happy with any election anymore. Presidents Bush and Obama may well be the last loyalty-backed presidents. Indeed, barring a major military threat that unites the nation against a common enemy and brings back a loyalistic approach, most future presidents may well be one-termers.

That’s worth repeating. We may be entering an epoch of one-term presidencies. We’ve already seen the voters moving this way with their seeming schizophrenia in presidential versus Congressional elections. They routinely put one party’s candidate in the White House and simultaneously fill the Congress with the opposing party.

Solutions

Again, what the voters really want is a truly on-demand system, where they can elect national leaders and direct their actions issue by issue, “no” on this, “yes” on that—preferably with a click of their computer—er, smartphone. This is leading in the direction of more democracy, specifically a more democratic system built around online voting. And, honestly, most modern Americans see this idea as excellent, obvious, and overdue.

In response, I have two words:

- Federalist.

- Papers.

If you have studied them in depth, you know exactly what I mean.

But most people haven’t.

And that means we’re in for a wild political ride just ahead. It might contain a series of one-termer presidents (the nation swinging pendulum-like to and fro, then back again, over and over), a serious party shakeup with a new dominant national political party (or two), or it might be something even more surprising.

Whatever is coming, there is a widespread sense that it’s big. And we don’t even have Steve Jobs to walk out on a black stage in his black t-shirt and announce the future. If he were still around, he’d tell us to hold on to our hats, because this flight into the Era of populism, globalism, voter pragmatism, and digital-age on-demand revolution is just beginning. And the only thing we know for sure is that it’s going to get bumpy.

(Solution: It’s more important than ever for regular people to deeply study the core principles of freedom! The politicians and “experts” aren’t going to fix this for us—they’re the ones piloting the current chaos. For a beginning reading list of core freedom principles—and audios to go with each— join Black Belt in Freedom)

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Education &Featured &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History &Independents &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Mission &Politics &Producers &Statesmanship &Technology

Why Populism? by Oliver DeMille

July 6th, 2016 // 7:46 am @ Oliver DeMille

Pendulum Swinging

We’ve heard a lot about populism during the election, and we’re going to hear a lot more. Why? Because the elite media is in serious shock.

We’ve heard a lot about populism during the election, and we’re going to hear a lot more. Why? Because the elite media is in serious shock.

They expected Hillary Clinton’s success, but the rise of both Trump and Sanders has astonished them.

Result: they’re writing and talking a great deal about “populism,” and the “dangers” it brings to our nation.

By the way, these tend to be the same journalists and media professionals who consistently tout the United States as a “democracy,” not a “republic” or “democratic republic.”

They promote “democracy, democracy, democracy” as the greatest governmental system ever, and then act shocked and worried when populism shows up to an election.

The irony is that populism is simply what happens when more voters than usual get actively involved in the process. In other words, America engages in populism during the years it acts the most democratic. Why are the elites concerned?

Answer: They like the kind of “democracy” where the masses are consistently swayed by the media—where expert elites tell the populace what to believe, and the electorate votes accordingly. This is what most members of the elite class actually mean when they use the word democracy.

Personally, I like Francis Fukuyama’s definition. He said:

“‘Populism’ is the label that political elites attach to policies supported by regular citizens that they don’t like.”

Funny how that sentence is written. Does is mean the political elites don’t like the policies? Or that they don’t like the regular citizens? I think it means the latter. But maybe not. Perhaps it means both the policies and the regular citizens.

Fukuyama notes that populist voters sometimes choose poorly, but “elites don’t always choose correctly either.” Very true. And in our current historical context, the worst-case scenario would be another elitist choice for president. Elites have increased in power far too much in the past three decades, and it’s time for the pendulum to swing back to the power of the people.

I. 3 Positive Developments

Here’s the “good news,” so to speak, about the current rise of populism:

#1

As Fukuyama also pointed out, this wave of populism is weakening both of the major political parties. The Democrats are losing large segments of their working class base and moving even more to the party of “a bunch of special interest groups,” while Republicans are almost violently split between the “big business crowd” and working class voters. Indeed, working class populists from both parties are now behaving like a formidable force.

#2

On a structural note, the framers of the U.S. Constitution didn’t want the president to be elected by mass vote. This is why they established the Electoral College—which originally worked with each state sending its representatives, rather than the people voting in a mass presidential election at all.

Fortunately, the people usually sense it when things are out of kilter. The framers put the people in charge of electing the House of Representatives in large part because the House controlled the nation’s money. But since the House seldom uses its power of the purse anymore like it should, and the White House now has the de facto say over money, the people are using their power to choose a president—like they once would have selected members of the House.

This structural shift if ironic: The masses, divided by congressional district (which is exactly how they oversaw the purse strings under the original Constitution), will select the president and largely determine the future spending of our nation. In other words, if the House shirks its job, the people switch their populism to the branch of government they think will do their will.

The elites see it happening, and they can’t stand it.

#3

Maybe that’s the best thing about this election. Regardless of what you think of Sanders or Trump, both candidates have thrown a serious wrench into the way elites view the world. They are reeling. They aren’t in charge of this election like they assumed they would be—not so far, at least.

Make no mistake, they’ll get their bearings again and get back to their agenda—to grow government and increase the power, wealth, and influence of the elite class. They always do. This won’t keep them down for long.

But populism seems to be growing. Sanders and Trump didn’t create this momentum, they just benefited from it. Populist elections changed the power of Congress in 2010 and again in 2014. In 2016 we’ll find out if populism makes it to the White House as well. Again, however you feel about the specific candidates, the rise of populism is a positive in a nation where elites control far too much.

2: A DEEPER LOOK AT THE CONSTITUTIONAL STRUCTURE (THEN VS. NOW)

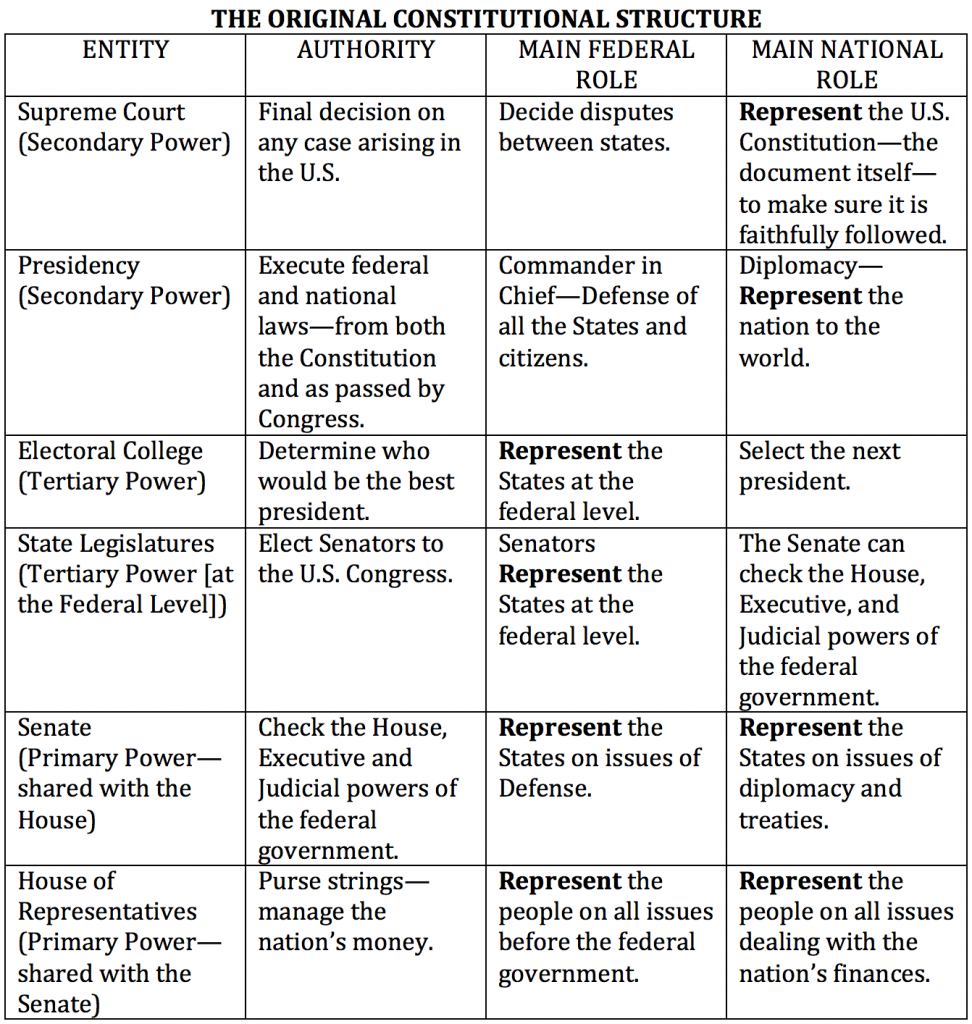

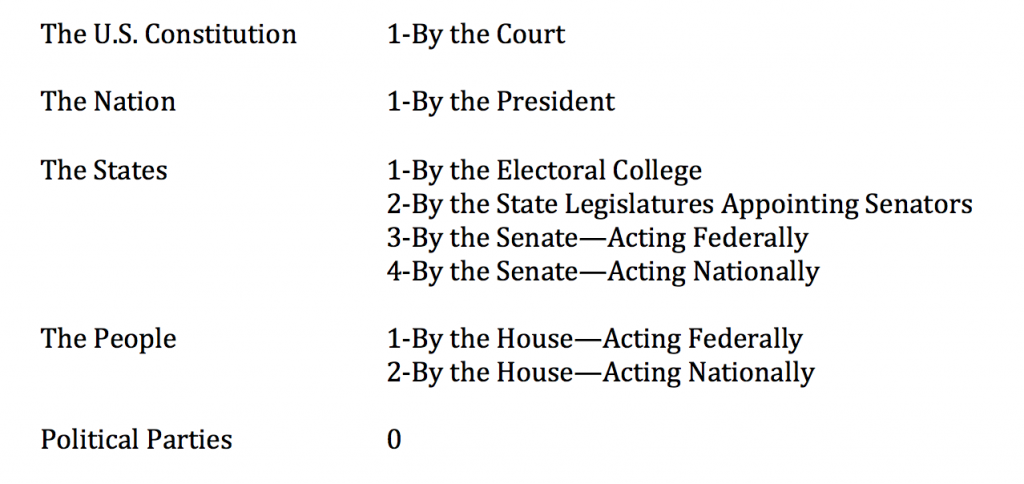

To see just how populism is important, let’s delve a bit deeper into the structural change to our governmental system. The framers established the following three branches and six entities to participate in the federal level:

Note that the following received direct representation under the provisions of the original Constitution:

This entire arrangement was carefully thought out by the framers. They knew that the key to lasting freedom was to ensure that the States didn’t lose their power to the federal/national government, so they put in four protections against this (listed above). All were wiped out by the poor decision to adopt the 17th Amendment in 1913. (Ironically, this was ratified during an era of populism.)

Our oversized and overblown national government and corresponding loss of freedoms since that time are the natural result. The best solution would be to repeal the 17th Amendment and restore the proper balance of State and Federal powers.

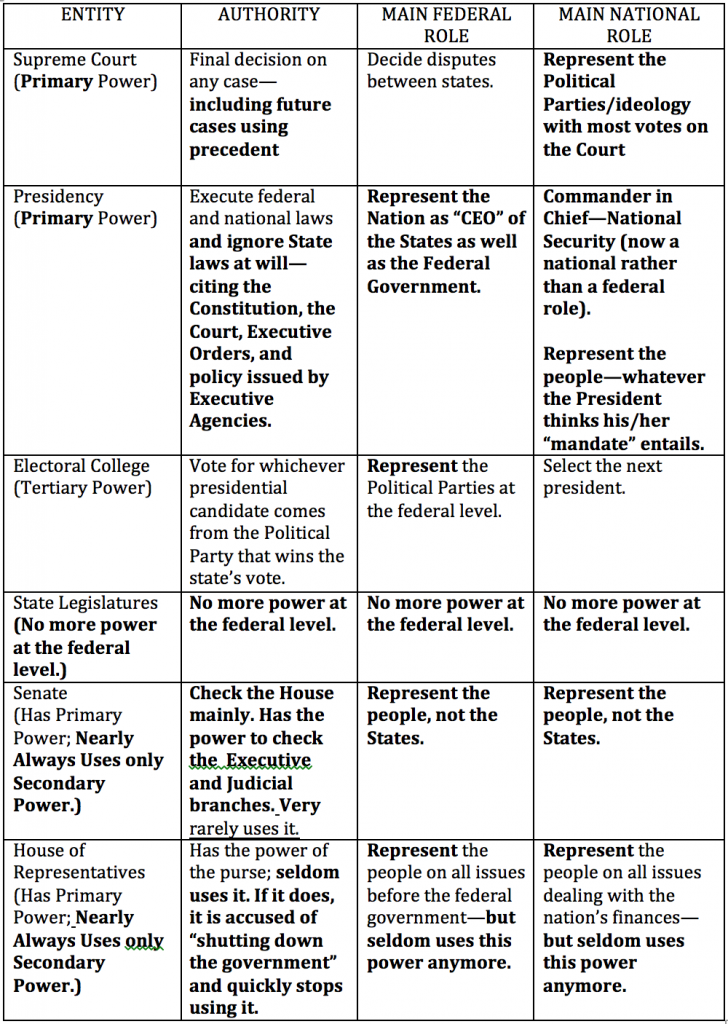

The following chart shows how the government currently operates. Note that it is very different than the original constitutional arrangement:

THE STRUCTURE TODAY

(Items underlined are changes from the original Constitution

that are destructive to freedom.)

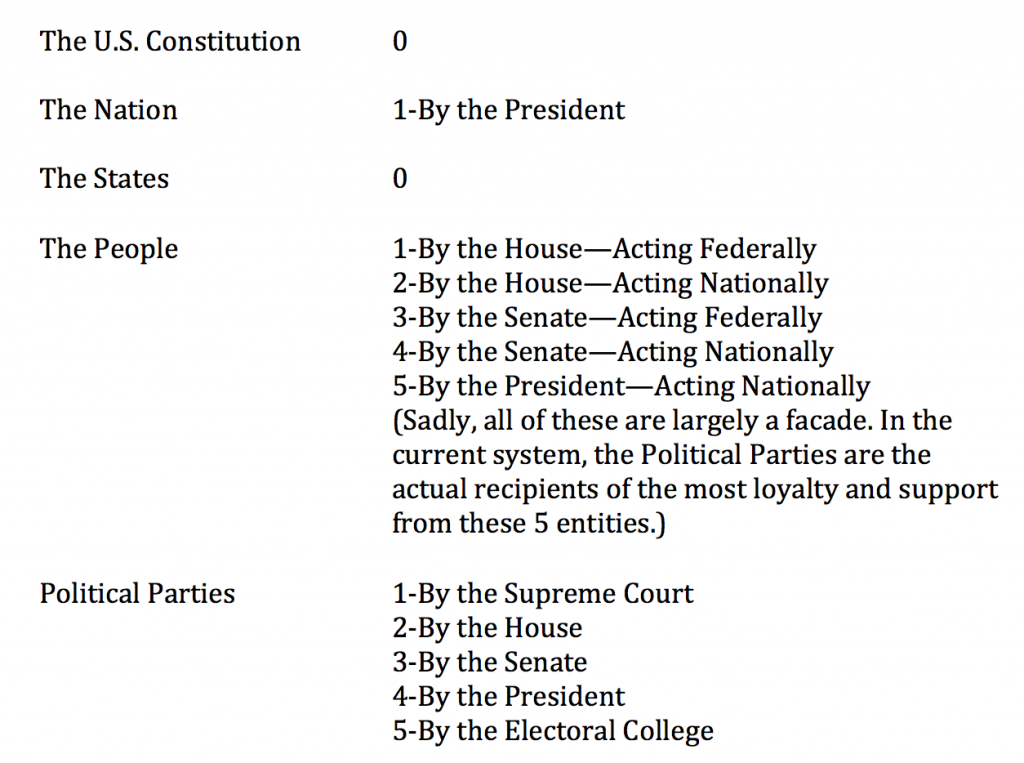

Look at how this has changed our governmental structure of representation:

Did you notice in all this that at the time of the American founding the primary entities of federal/national government were the House and the Senate, while the Court and Presidency were secondary? Compare that to now: the Presidency and Court act like primary branches of government, while the House and Senate act like secondary levels of government.

What the founders called “legislative primacy,” meaning that the people’s elected representatives in Congress had the final say on things through the purse strings, has been replaced by appointed officials in the Court and a huge Executive bureaucracy exerting the final say on most things.

Huge changes. All bad!

For The People

Now, if you’ve followed this article this far, congratulations! Here is the main point, the thesis, the reason for reading this and thinking about it:

Populism is attempting to correct the course of the American ship. Specifically, the populist elections of 2010 and 2014 both attempted to put the House and Senate back on track representing the people—not the political parties.

And the populist uprising of 2016 (among both Democrats and Republicans) is also arguing for the presidency to represent the people again, not the political parties. It’s not as good or as effective as repealing the 17th Amendment—not by a long shot—but at least the electorate is trying.

The voters (some knowingly, and most of them just by following their gut) are attempting to swing things back in the direction of government “by, of, and for” the people—instead of government “by, for, and of” the economic and power elites and their political party establishments.

Populism probably can’t get the ship all the way safely into port, but right now the people are at least trying to get things going in the right direction. If the voters keep at it, and don’t give up—and if they keep winning major elections—this new beginning can eventually be turned in the direction of a real and lasting solution.

Stay tuned…

Category : Aristocracy &Citizenship &Community &Constitution &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Education &Entrepreneurship &Featured &Foreign Affairs &Generations &Government &History &Independents &Information Age &Leadership &Liberty &Politics &Statesmanship

Representative to Popular Form

June 7th, 2016 // 10:12 am @ Sara DeMille

Guest Post by Ian Cox

Midlife Crisis of U.S. Politics?

Most voters think that whichever candidate gets the most votes will take the nomination for their party, but the reality is more complex.

Most voters think that whichever candidate gets the most votes will take the nomination for their party, but the reality is more complex.

More people are hearing about the “contested convention” that looks likely for the Republican Party. Even the Democratic race has seen a similar shake up: Sanders often takes the popular vote, but Clinton wins more delegates.

As Ezra Klein from vox.com put it:

“Americans believe their elections are far more democratic than they actually are, and that’s because the most undemocratic institutions—like super delegates and the Electoral College—tend to follow the popular will. But that’s because the popular will is usually clear and easy to follow.

“This is a year, in other words, when voters on both sides will be looking for reasons to doubt the results of their primaries. And they will find plenty of them.”[1]

In a contested convention for the Republican Party most delegates will be able to vote however they would like. This will probably leave their constituents back at home a little upset if they don’t follow the popular vote. Maneuvering has already been taking place to get delegates who are sworn to one candidate by their State’s popular vote, but who would vote for another candidate in case of a contested convention.

Democrats have super delegates who aren’t tied to popular vote and can cast their vote wherever they see fit. They may “pledge” to one candidate during the primaries and this usually coincides with the popular vote of their state, but it doesn’t have to.

These are just two aspects of the labyrinth of a republican form of government. In other words, a government by delegation or by representation. Every state has its own method of voting for the president, as well as party rules, and how the state itself runs.

Which One?

The question arises here, are we a government of delegation or a government of popular vote? It seems that the people think it’s popular vote—and get confused, annoyed, and angry when thwarted. But the party leaders and government are living by the rules of representation (granted, this is pretty much by default because they are required by law to abide by these rules).

The people are playing Baseball while the delegates are playing Football, and the rules of the two games don’t mix very well. In the overlap, we’re getting major chaos and only one side can prevail.

Before we continue, let’s take a few steps back and take a good look at these two forms of government.

Popular vs Delegate Societies

A pure democracy exists where the majority decides what happens. If 51% of the population wants free health care, then it passes a law and it’s the duty of the officials to make it happen. If 49% wish for slavery, they can’t pass as law because there is no majority.

Things move quickly, and usually vehemently, in a society ruled by solely popular vote. Even Aristotle categorized democracy as a bad form of government. Most of the founding fathers studied many different forms of government as they were putting together the Constitution of the United States. John Adams said:

“Democracy… while it lasts is more bloody than either aristocracy or monarchy. Remember, democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There is never a democracy that did not commit suicide.”

Think of the book Les Miserables by Victor Hugo, or The Scarlett Pimpernel by Emma Orczy, or any history book covering the French Revolution, and you’ll get the picture of what everyone was so worried about when it comes to democracies.

On the other hand, a republican form of government exists where the populace gets together and votes for delegates or representatives who then decide what laws to establish. Instead of the populace voting for everything, their representatives or delegates take the duty to maintain society through necessary law-making and executing those laws. A classic example of this is the Roman Republic or the Roman Senate.

Another great example of this is our modern Presidential election. Every four years we have a national election—which is partly done by popular vote and partly done by a delegated vote, depending on the state—and a great number of citizens rally around this great cause. Once it is over most people hibernate again until something exciting comes along, like the next presidential election.

If you’d like to know more of what the role of the average citizen should be during this “downtime,” dig into these two books Oliver DeMille wrote for this very purpose:

- Freedom Matters by Oliver DeMille

- The U.S. Constitution and the 196 Indispensable Principles of Freedom by Oliver DeMille

What Is Our Identity?

When the endgame is unknown it’s pretty much impossible to win. If I’m given a golf ball on a soccer field, and I’m told to make the loop, what am I supposed to do? What if I’m not given any instructions? Am I supposed to be on offense? Defense? Maybe play goalie. Is there even supposed to be a goalie? Am I allowed to block, where am I to focus to help score, do what I want a high score or a low score? Is there a scoreboard?!

Not knowing what you don’t know can be very frustrating, stressful, and leave you without any hope of making progress. We no longer seem to be a nation with a unifying identity. A similar thing happened in the 1770’s between the colonies and the British, again in the 1850’s-60’s with the Northern States and the Southern States, also during the 1940’s with bigger government deals as well as global community issues. We’re in another such period; over the next few years we will likely see society shift again in major ways.

Will it be a shift towards more opportunity, success, and freedom, or something worse?

What is the Coming Shift?

It might be too soon to tell, but this presidential race might just be an omen of the coming shift; a microcosm of what the future holds for the “United” States of America.

This disconnect and misunderstanding of how the elections actually work could be the perfect setting for a democratic revolt. The populace might demand, despite whatever laws, rules, and constitutional measures are in place, that government listen to the voice of the people. To do what the people vote for and right away. No more of this arguing, debating, and political maneuvering in Congress. Let’s get it done!

The checks, balances, and the democratic republican constitutional form of government we now see hanging by a thread could very well be severed and swing us heavily towards a government by the whims of men.

Now, because of the numbers, I know many who read this will still be asking: but why is this shift a bad thing? Isn’t it bringing us more freedom? Isn’t it getting the people what they have so long desired? No more ridiculous laws or government officials telling us what we can and cannot do; we will take the responsibility in our own hands!

If men were angels this would probably work out much better, but as history has shown again and again this is not the case. Remember the quote by John Adams earlier? Remember your French Revolution history? Logically we might “know” these things, but still! Look at what’s happening today in our society. The people are being held back as corruption in high places seeps further and further.

Who will win this fight? The corrupting upper crust of society, or the beaten down and squished populace?

Or is there a third option?

Another Way

Think of it this way: when societies were ruled by the whims of the masses, the leaders that rose to the top were Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, Nero, and the like. Historically these are the type of men, and women, who rise to the top and gain control.

On the flip side of this coin is the rule of the wealthy or privileged. Enter the Feudal Age and the ancient and modern systems of slavery. King Henry the VIII wasn’t elected or put on the throne by a revolution of discontented people, he was born into the position. He was at times just as bad for the people and to the people as the tyrants mentioned before. That’s because these monarchs or oligarchies still rule by the whims of men.

What our Founders did differently—as did every other truly free people in the history of the world—was study freedom deeply, and then build organizations or communities that solved the issues of their time. In other words, they took responsibility to get things done themselves, and they developed their leadership to make sure their ventures and communities would succeed.

Let’s Pay the Price

What every free people in the history of the world did different was set up checks and balances, forms and processes, and auxiliary precautions to guard against these destructive tyrants, both of the general people as well as the individual tyrant and everything between. It’s safer in the long run to establish laws, rules, and forms that are no respecters of persons. This has been the formula for establishing freedom for generations.

This means the rules of the game must be understood and upheld by the masses. If the average citizen doesn’t, then we’ll quickly learn to vote for any and every benefit we can. Or we’ll have the threat of having our representatives and upper crust of society take power and rule with an iron fist—squashing the general populace.

I’m not saying the current forms and systems are perfect, but we should understand why they were established in the first place. If we throw off the bonds that make us free we will quickly spiral into an era of major losses of freedom and opportunity for generations to come.

Let’s pay the price of understanding the rules of the game to maintain freedom.

[1] “This presidential campaign is developing a legitimacy problem,” by Ezra Klein Vox.com, April 19, 2016

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Citizenship &Current Events &Government &Independents &Liberty &Politics

3 Things We Aren’t Talking About Enough by Oliver DeMille

May 19th, 2016 // 8:19 am @ Oliver DeMille

These three things are big deal. A very big deal. They’re floating around there in the back of our minds, but we don’t talk about them very much in our current society.

These three things are big deal. A very big deal. They’re floating around there in the back of our minds, but we don’t talk about them very much in our current society.

We need to start.

I

First, it is clear to almost everyone that the Drone Revolution has drastically changed the world—probably in ways that we can’t really undo. Whatever other functions they’ll eventually fulfill, drones are the ultimate war machine. They can be programmed to do things unimagined in earlier wars, like search out specific people from certain races, religions, viewpoints, business or educational backgrounds, etc.

They can be programmed to target a specific person. And all his/her friends. Everyone he/she loves. Those who agree with him/her on political issues. Governments can use drones on their own people, as well as in battle.

Very few people are taking this very seriously. On the one hand, it’s so potentially monstrous that we don’t like to think about it. Imagine drone technology in the hands of a Stalin, a Hitler, a Nero, Caligula or Mao, Saddam Hussein or an ISIS sympathizer in your neighborhood. If history has taught us anything, it’s that bad guys do sometimes rise to great power.

It will happen again, and drone tech combined with computing power is a recipe for disaster.

On the other hand, if we did want to stop it, what would we do? Most people believe it’s a fait accompli. No chance of turning it around. They’re probably right.

II

Second, the Crowdsourcing Revolution isn’t over—it’s just beginning. It has largely put the newspaper industry on the ropes, and the book industry is also now under the gun as Amazon grows. In fact, many brick and mortar malls are increasingly empty as Internet sales on many types of products and services soar. Education at all levels is facing serious competition from free online learning sources, and big swaths of the health care sector are being crowdsourced as well.

The good side of crowdsourcing makes a lot of things less expensive, easier to find, and quicker to obtain (or learn). The downside is that the large companies that control the data have algorithms that can influence us in ways we never imagined. For example, a man texts his wife to find out where a certain kind of cereal is in the pantry, and within minutes his smartphone chimes and offers him a coupon for the same cereal—from the supermarket closest to his home. Or if he texted from the office, it lists the grocery store nearest to his work.

This kind of data-mine-marketing is becoming a commonplace experience for those who use certain apps, and while it might feel a bit creepy at first, over time people get used to it—and even grow to expect it. Very Minority Report. How much governments and private organizations are using this kind of tech is unclear, but it’s growing. Add personal location tracking technology to the mix, and we really are living in a surveillance state.

III

Third, there’s a new buzzword floating around in economic circles: “Crowd-Based Capitalism.” The idea is that in the emerging 21st Century economy we’re evolving a whole new economic model. Not socialism. Not capitalism. Certainly not free enterprise. A new approach. As one book from MIT put it, we’re moving into a “Sharing Economy,” where “the end of employment” is being replaced with “the rise of crowd-based capitalism.”

The idea that employment as we’ve known it for the last six decades is increasingly outdated. For example, in the May 2016 issue of The Atlantic an article showed how one couple used up their entire life and retirement savings—and the entire life savings of the husband’s elderly parents—to put their two daughters through college. The idea of college training being essential is now being taken to incredible levels: The savings of two couples wiped out, just so their offspring could graduate with a degree—in an economy that doesn’t value degrees like it used to. (See “My Secret Shame,” The Atlantic, May 2016)

A truly new economy is emerging, but most people haven’t realized it yet. They’re still caught in the old—and paying for it in tragic ways.

Another example: When 2016 presidential candidate Ted Cruz said the following, “The less government, the more freedom. The fewer bureaucrats, the more prosperity. And there are bureaucrats in Washington right now who are killing jobs…”, the response was immediate. Two professors, one from Yale and the other from Berkeley, replied that the opposite is true: The bigger the government, the more freedom, and the bigger the bureaucracy, the more prosperity. (“Making America Great Again,” Foreign Affairs, May/June 2016)

A lot of people actually believe them.

But reality is still reality. Crowd-based capitalism means more government, and this isn’t the path to a great economy. The thing that is actually rising to replace the 1945-2008 era of employment it is a reboot of entrepreneurship and small business ventures.

The new economy can go in one of two directions:

- Government reduces the amount of anti-business and job-stifling regulations, and spurs a major entrepreneurial boom. This will create a lot more jobs, opportunities, and incentives for increased global investment in the U.S. economy.

- Government keeps increasing business-stifling regulations and takes the profits from businesses (big and small) to create a “sharing economy.” This will create a much higher rate of dependency on government welfare and state programs, reduce the number of people fully employed (making enough to live in the middle or upper class), and drive investment to other nations.

How the so-called “sharing economy” differs from socialism is actually academic. Yes, on paper it has a somewhat different structure than Marxian socialism. But for the regular people it’s going to feel pretty much the same. A few wealthy and powerful elites at the top, a small middle class of managers and professionals who work mostly for the elites, and a burgeoning underclass living largely off government programs.

Two books* on this topic are: (1) The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism by Arun Sundrarajan, and (2) Saving Capitalism: For the Many, Not the Few by Robert Reich.

For the other side of the argument—why freedom and free enterprise are the real answer—see my latest book, entitled Freedom Matters.

Middle America is still experiencing a serious economic struggle. Things are getting worse, not better. As one report on the heartland put it: “On every sign, in every window, read the vague and anxious urgings…Remember the Unborn; …Don’t Text; Don’t Litter; Buy My Tomatoes (Local!); Let Us Filter Your Water; We Can Help With Your Bankruptcy. Then bigger gas stations sprawled on crossroad corners, unoccupied storefronts…another consignment store.” (“The Country Will Bring Us No Peace,” Esquire, May 2016)

As an ad for Shinola products reminds us: “There’s a funny thing that happens when you build factories in this country. It’s called jobs.” We haven’t seen very many factories built here for a long time. Crowd-based capitalism isn’t a solution.

Conclusion

Together, these three changes in our world are a very big deal:

- The Drone Revolution

- The Crowd-Sourcing Revolution

- The Post-Employment Economy

If you have more ideas on these important developments, share them. If not, learn more about them.

The future can be determined by a few elites who think about such things, or by all of us. The more regular people engage such important topics, the more influence we’re likely to have.

The truth is, we’ve forgotten Watergate and Kent State. (See “The Cold Open,” Esquire, May 2016) We’ve forgotten Nixon and that the 2000 presidential election was decided by the intervention of the Supreme Court. (Ibid.) We’ve forgotten a lot of things.

As one report put it: “We’ve forgotten how easily we can be lied to.” (Ibid.) If we let them, Washington and the media will just tell us what the elites want us to know—and think.

*affiliate links

Category : Aristocracy &Blog &Business &Culture &Current Events &Economics &Entrepreneurship &Generations &Government &Independents &Information Age &Liberty &Mini-Factories &Politics &Postmodernism &Prosperity &Technology

Winner Take All – Trump and the Supreme Court by Oliver DeMille

May 18th, 2016 // 12:40 pm @ Oliver DeMille

by Oliver DeMille

The 2016 election is a watershed event for America. If Democrats win the White House, the United States will be a very different place from now on. And not in a good way.

The 2016 election is a watershed event for America. If Democrats win the White House, the United States will be a very different place from now on. And not in a good way.

As an independent, I try to avoid acting like one party is wonderful while the other is just plain “evil.” I know too many partisans—in each of the two big parties—who see the world in this kind of black and white. But there are too many flaws in both parties to think that either of them is the true answer to our nation’s problems.

Except this year. This time things are different.

How? Put bluntly, the death of Justice Scalia has created a serious situation in the Supreme Court. For years we’ve seen a precarious balance on the Court, with close votes sometimes swinging to conservatives and other times to liberals. Scalia was always a sure thing for conservatism, and even with him on the bench progressives won too many cases that hurt our nation.

The only way conservatives keep any semblance of balance on the Court is to fill Scalia’s seat with another died-in-the-wool conservative. Put a liberal or moderate on the Court, and things will drastically shift socialistic for the next decade—or more. And yes, I mean to use the word “socialistic.” This is precisely what will occur.

Such a future will increase government-run health care, educational decline, taxes, intrusive gun laws, a continued loss of state power to Washington, more regulation, bigger government—and a lot more Washington intrusion into our lives, cradle to grave. I think Americans will be amazed at how quickly our freedoms will decline with a patently liberal Court.

Whoever wins the White House this year, it better be a Republican. With Donald Trump as the nominee, it’s a dilemma for some voters. Not for me. I’ve been critical of Trump on a number of issues, but now it’s down to reality:

I don’t know how well President Trump will do in putting the right kind of justices on the Court, but I do know that President Hillary Clinton’s Court appointees will ruin our nation. And fast.

You can call my opinion too political if you want, but I’m absolutely convinced that it’s true. A Clinton victory will bring major negative change to America—especially on the Court. It’s time to get behind Trump and make sure he wins.

Whatever happens, this election has true conservatives and constitutional-focused independents biting their nails. Election night won’t just determine the next president. More than at any point since 1980, this election marks a major turning point for freedom in America—either good or bad. A true fork in the road. The Trump fork may or may not work out very well, but the Clinton fork would be cataclysmic. It’s winner take all, and the prize is the future of the United States.

Category : Blog &Constitution &Current Events &Government &Independents &Leadership &Statesmanship